When the United States of America, as a shiny new nation, was eager to establish its ‘new world order’ this, predictably, ruffled a few of the older, more established nations’ feathers.

First, they demanded Canada. Britain, predictably, declined, and the US, perhaps realising they had come into negotiations a little gung ho, instead settled to agree on where the northern border would reach. These various negotiations over US and British territory went on for some time, until 1846 in fact, when the Oregon Treaty attempted to literally draw a line in the sand between the territory of the two nations. The hotly contested territory was the Gulf of Georgia, a straight between British Columbia and Vancouver island; it was decided that the divide would lie:

“along the 49th parallel of north latitude to the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver Island, and thence southerly through the middle of the said channel, and of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, to the Pacific Ocean.”

All these technical terms seemed pretty exact, but what those present had failed to notice was that a little cluster of islands lay around the bottom of the gulf; there were TWO passages through them, and the terms didn’t indicate where the divide should lie. To add to the confusion, the maps available of the region weren’t really up to scratch, and both nations left the negotiations with very different ideas of where exactly this boundary lay.

The blue line represents the boundary as understood by the Americans, while the red is through Rosario Strait, Britain’s preference. The green is the compromise that was proposed by the British.

Once the two nations realised that both thought they owned the same collection of islands, they were quick to defend their claim:

“I know there is one close round Vancouver’s Island, but I believe the largest to be the one Vancouver sailed through, and I think this is the one which should be the boundary,” said Sir John Pelly, head of the Hudson’s Bay Company on behalf of the British.

The Americans, obviously, didn’t agree and both nations dug their heels in. The islands themselves weren’t particularly remarkable, they didn’t possess any towering mountains or deep harbours. They were mostly covered in dry grassland, pines and red cedars. An offer to cede all islands to the US except San Juan Island was rejected and both negotiators agreed to report back to their governments and reconvene on the matter at a later date, whenever that may be.

As far as the British were concerned, the islands belonged to them. San Juan island in particular was a great strategic boon, and there was no way the US was going to get its greedy hands on it. Confident that the chips would fall in their favour eventually anyway, the island was leased out to the British Hudson’s Bay Company for the sum of seven shillings a year.

On 15 December 1853 the company transported 1,300 sheep, as well as a few pigs, to the island as the start of a sheep ranch. The whole operation was put under the charge of Charles Griffin, aided by a few Hawaiian herdsmen. Griffin quickly made himself comfortable, setting up a few buildings he dubbed ‘Belle Vue Farm’ and prepared to settle back and enjoy the quiet life.

But Griffin’s peace wouldn’t last long. In 1858 gold was struck in the region; thousands of excited American gold seekers flooded to the islands. Between April and July alone, 16,000 treasure seekers set sail and the region was transformed. Although most of them returned home for the winter, some decided to settle, and a few of them reached San Juan Island, built cabins and claimed land for their own use. In all, 25 Americans set up residence, while the British population remained the same – one Irishman and a few Hawaiian herdsmen.

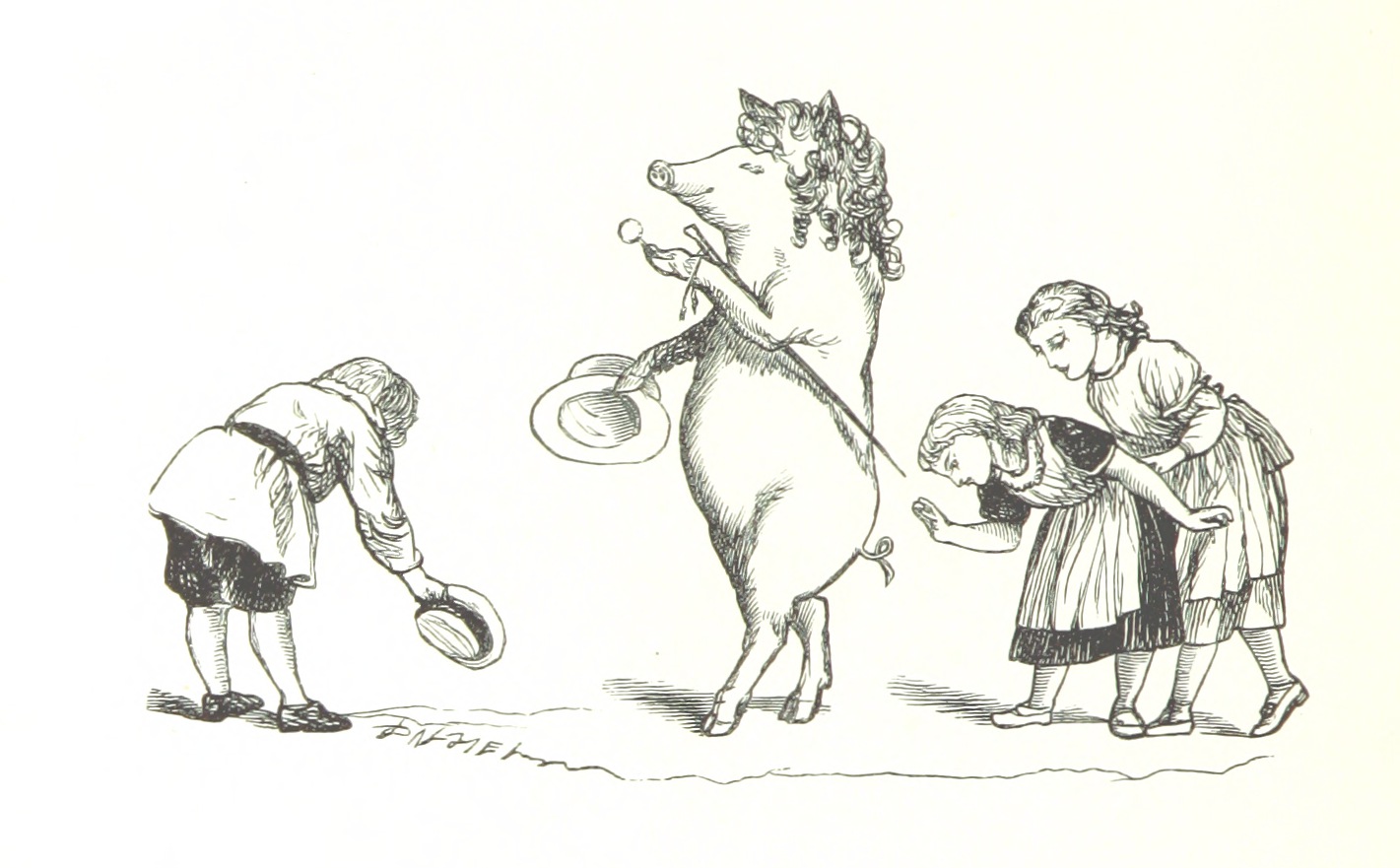

One of these Americans, a man named Lyman Cutlar, with thorough belief that the land was his by American right, dug up a third of an acre of one of Griffin’s sheep runs. He was also, unfortunately, a particularly terrible builder of fences, and one of Griffin’s pigs managed to manoeuvre its way through and gorge itself on the delicious potato feast lying beyond. Cutlar would later claim that the animal had “been at several times a great annoyance.”

Regardless of whether this was true or not, he took an action that would have consequences bigger than he could have ever possibly imagined – he shot the pig.

To put it mildly, Griffin was upset. He had sat and watched these Americans move into his land, and now they had attacked one of his own animals. This was, to put it frankly, simply not on. He marched over to Cutlars house and demanded compensation for his loss. Cutlar, probably a little bewildered by this angry Irishman on his doorstep, offered $10 for the pig.

This was not what Griffin wanted to hear. The pig, he explained, was a prize breeding boar and was worth at least $100. At this, Cutlar did an about turn. Why should he have to pay anything? The pig had, after all, been trespassing on his land. The situation got rather heated and Cutlar ended the confrontation with the retort that he would “as soon shoot [Griffin] as he would a hog if [Griffin] trespassed on his land.”

By pure good, or bad, luck (depending on your outlook), a Hudson’s Bay Company vessel carrying three people who considered themselves very important drew into the island that afternoon.

These three men, Alexander Dallas, Dr William Tolmie and Donald Fraser, were all in charge of various factions of the company’s land and Griffin was all too eager to let them know about the incident with the pig. The men rode to Cutlar’s house immediately and confronted him four on one. When asked how he would possibly do such a thing, Cutlar replied that the pig was ‘worthless’.

The others meanwhile, were quick to ascertain that the island was a British possession (and then so was the pig) and that if Cutlar didn’t cough up the dough he would be arrested. Cutlar, now grasping his rifle, insisted that “this is American soil, not English!” Confronted by an angry American farmer and the business end of his rifle, the British promptly left, but not without a last retort of: “You will have to answer for this hereafter!”

This disastrous clash of British stubbornness and American pride quickly spiralled out of control. Cutlar was not at all willing to take all the British threats lying down and the American authorities were soon informed that he had “offered to pay to the company twice the value of the pig,” (which considering Cutlar had proclaimed the animal to be worthless, this wasn’t strictly untrue). And it was deemed necessary that “for the protection of our citizens” American soldiers be dispatched.

66 American troops soon disembarked and set up camp on the island. Not to be outdone, the British responded by sending three warships.

Pickett, in charge of the American troops, did a mighty good job of hiding his reasonable alarm at this escalation and proclaimed “We’ll make a Bunker Hill of it!” and so American reinforcements came by the bucketload.

By early August 1859, 461 Americans with 14 cannons faced a now-increased British fleet of five warships with at least 70 guns and 2,140 men. The British could clearly take the island if they wanted to, but they, like their American counterparts, had received strict instructions – stay on the defensive, make your presence felt, but whatever you do, don’t shoot first. Barnes, the British Rear Admiral, was inclined to agree, stating that “two great nations in a war over a squabble about a pig” was foolish. And so the two forces waited and waited, letters were sent back and forth and insults yelled from one camp to another, but not a single shot was fired.

As often is the case, the last people to hear about the potentially explosive situation were the leaders themselves. James Buchanan, then serving as President of the United States, had his own problems. His country was crumbling all around him and on the brink of civil war – the absolute last thing he needed was to start a war with the mightiest empire in the world over a pig.

Accurately noting the ‘tense’ nature of the situation, he sent General Winfred Scott, who had already calmed a few border disputes between the two nations, to smooth things out.

The conclusion of these negotiations were about as far from a resolution as they could get. Both nations agreed to scale down their forces to no more than 100 men, and jointly occupy the island, with both flags flying proudly in their respective camps. So basically neither agreed to cede to island to the other – which was pretty much where the whole mess began.

Unbelievably, this set-up continued for 12 more years. For 12 years the British and Americans carried out their own operations at their respective camps. However, unlike Griffin and Cutlar, they were rather amicable neighbours. The Americans invited the British to celebrate 4 of July with them, while the yanks would visit the British for Victoria’s birthday celebrations. The biggest threat to peace at this time was the enormous amount of alcohol, as well as shady suppliers, that appeared on the island.

The two forces waited until finally, in 1872, all of the two nations’ remaining squabbles were brought out into the open. One by one all the border grievances remaining were addressed and (mostly) resolved, until eventually the focus fell on San Juan Island. It was decided that because the two nations both insisted on stubbornly claiming the land, the fate of the island would be decided by international arbitration, with no other than Kaiser Wilhem I of Germany to act as arbitrator.

The Americans were very clever with their choice of representation – George Bancroft had studied in Germany and had many powerful German connections. The British representative, Admiral James Prevost, although a talented negotiator, was a virtual unknown in the country. After months of deliberation, a decision was made:

“Most in accordance with the true interpretations of the treaty concluded on the 15th of June, 1846, between the Governments of Her Britannic Majesty and of the United States of America, is the claim of the Government of the United States that the boundary-line between the territories of Her Britannic Majesty and the United States should be drawn through the Haro Channel.”

The Americans had won. The island was theirs. It didn’t look like Griffin would be getting that $100 any time soon.

After years of joint occupation, on November 1872 the British forces finally withdrew, the Americans followed by July 1874, and so ended a cold war lasting almost 20 years that had produced only one casualty – a particularly hungry and curious pig. Today on San Juan Island the Union Jack still flies where the British Camp used to lay, and is raised and lowered every day by rangers. We can only hope that any pigs on the island are firmly penned in by strong fences.

For more unusual tales from history, pick up the new issue of All About History or subscribe now and save 25% off the cover price.

Sources:

- The Pig War: The Most Perfect War In History, E.C Coleman

- The Pig War: The Last Canada-US Border Conflict, Rosemary Neering

- The Pig War: Standoff At Griffin Bay, Mike Vouri