The Korean War is a wrongly neglected conflict that devastated Korea and dramatically escalated the Cold War. The United Nations fought for the first time to save South Korea from communist occupation and there were bitter battles fought between 1950-53 in horrendous conditions. In many ways the fighting was reminiscent of the two World Wars and one of those who experienced the conflict first-hand was a young British officer called Brian Parritt.

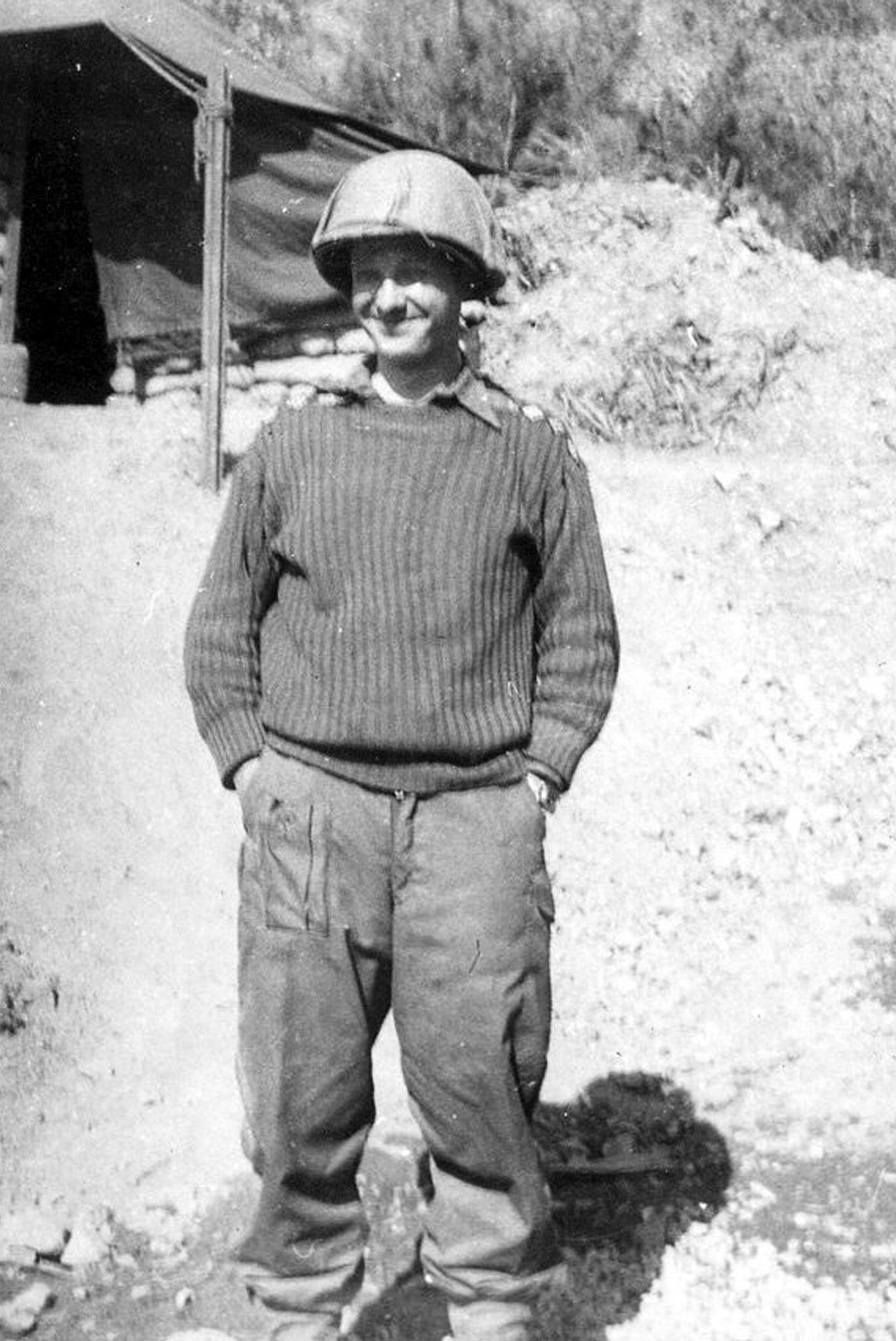

Parritt was a regular soldier who arrived in Korea in December 1952 as a second lieutenant in Baker Troop, Minden Battery, 20th (Field) Regiment, Royal Artillery. For over half a year Parritt and Baker Troop fought in one contested position known as ‘the Hook’ against numerically superior Chinese forces. Baker Troop fought with Ordnance QF 25-pounder guns and the fighting reached a crescendo between 28-29 May 1953 during the Third Battle of the Hook. This was a hard-fought engagement where the UN managed to throw back successive Chinese attacks.

Parritt was wounded during this battle and commended for bravery. After recovering in hospital he returned to the front line and witnessed the dramatic armistice that was declared in July 1953.

Despite the armistice, no peace treaty was ever signed and the war is still not technically over. After almost 65 years the Korean War still destabilises the peninsula it was fought over and in recent months tensions have increased to dangerous levels due to the belligerent rhetoric of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un and American president Donald Trump.

Although the 1950-53 conflict became known as the ‘forgotten war’, it is arguably more relevant than ever and History of War Issue 52 was privileged to speak to Parritt about his modestly told but compelling fighting experiences.

OFFICER TRAINING

What was your motivation for joining the British Army?

I was brought up in an army environment. My father spent 30 years in the artillery, my grandfather spent 27 years in the Royal Artillery with 13 years in India and his father was a full time Royal Artillery soldier in the Crimea. I was brought up in barracks. Its something that I always wanted to do to be a soldier in the Royal Artillery.

What did your officer training consist of?

I joined the army in November 1949 as a National Serviceman at Oswestry as a gunner and was an acting, unpaid lance-bombardier, which was the most difficult appointment I had in 37 years! I was trying to control a barrack room of Liverpool guys but I then went to the National Service selection and passed.

I therefore went to do officer cadet training at Mons Barracks in Aldershot and during that period for National Service training I took the RCB (Regular Commission Board), which I passed and went from Mons to Sandhurst. I had a couple of months preparation before the next term started and ended the three terms when I finished in February 1952. To our sadness we were the only intake that didn’t pass out, go up the steps or have a ball because the king [George VI] died on the day before the pass out parade. It was a mistake to cancel it because we should have carried on but it was cancelled.

While I was on the young officers artillery course you could select which regiment you wanted to go into. I knew the 20th (Field) Regiment were going to Korea so I applied with my friend Shaun Jackson and luckily we got selected.

When did you join ‘Baker Troop’?

That started then when we joined the regiment, which would have been around August 1952. Just after we arrived the colonel called us all on the square and said, “I’ve been posted to Korea.” He then paused and said, “And you’re all coming with me!” That’s when we knew it was true that we were going to Korea. There was then a hectic period of almost constant training. It wasn’t like peacetime when you are guards etc. It was training on concentrated fire, plans, drills and deployments.

We left Hong Kong in December and took over in the line in Korea on Christmas Day 1952.

What is the origin of Baker Troop’s name?

There are three batteries in each regiment and I was in 12 Minden Battery. In each battery there are two troops and 12 Battery was the senior battery. There was ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ Troop and then in the next battery there was ‘Charlie’ and ‘Delta’ Troop followed by ‘Echo’ and ‘Foxtrot’ etc.

ARRIVAL IN KOREA

What were your first impressions of Korea when you arrived in December 1952?

It was dark and desolate. Pusan was in total ruins but we didn’t see much of it. We went out very quickly after two or three days in the train all the way up to the front line. December in Korea is a dark, cold place anyway and you were struck by the desolation and the lack of people. It was pretty depressing countryside all the way up until we reached our gun positions.

How did it feel to be serving with the UN, which was then a new organisation?

There was no conception at all. No one ever commented that we were the United Nations. Our regiment was in a British brigade, which subsequently became the British Commonwealth Division. When the infantry went into reserve for a period the gunners stayed in the line because there was a shortage of artillery. We met the Americans, Thais and the French, which were under the banner of the UN but we were never really conscious that it was a UN organisation.

Where was Baker Troop based during the war?

We were based at a position at the ‘Hook’. We moved out from the position to do a firing task in support of other units such as the [South] Koreans but we actually stayed in the same position. It wasn’t like 14th Regiment and 45 in particular. We were the third. The first regiment, 45, went right up to the Yalu River and went back again, up and back supporting the Glosters, Ulster Rifles and Northumberland Fusiliers. They were always on the move but by the time we got there it was a static front line and we stayed in the same position.

Do you know the name of your position?

There was no name. It was just a field that was behind the Hook area.

LIFE ON THE FRONT LINE

You’ve said that the battlefield at the Hook largely resembled the Western Front of WWI, can you expand on that?

There was a line of hills, which we occupied with our gunner regiment behind the hills. On our line of hills various battalions would come to change occupying the Hook or [Hill] 355 in turn. Then there was a river valley called the Samichon and a similar line of hills on the other side with barbed wire on their side, barbed wire on our side and mines in the middle.

It was totally shell-pocked, barren, there were no trees because they had all been blown down. There were was no vegetation and it was just a bleak landscape that was similar to pictures of the Somme.

What went through your mind at the time considering that it was your first time in active combat?

It was natural and you would have expected it. It was cold but I was doing what a young officer in the artillery would hope to do.

You had four guns. You were either at the gun end controlling or ordering the fire of the guns or you had more excitement sitting in the OP looking over the Chinese lines. So it seemed a natural progression for a young soldier. People had already done it in Normandy and El Alamein or anywhere else.

What happened when you commanded guns for the first time?

When we took over in the line the troop commander who I replaced gave me a bottle of whisky and said “Good luck!” When I subsequently left at the end of the war I gave a bottle of whisky to the chap who took over from me and also said “Good luck!”

As a second lieutenant in command of four guns, how many men were you in charge of?

There were three officers. There’s the captain, a lieutenant and a second lieutenant. The second lieutenant is the troop officer. The four guns were each commanded by a sergeant in a detachment of six. There were four gun pits and they lived in those little holes all the time. I suppose there about 40-45 guys altogether.

Why was the role of the sergeants so important?

Actual responsibility would totally fall on the sergeants. I was sitting in the comparative warm of the command post and would order, “TARGET, TARGET” and they would have to run out of their ‘hoochie’ pit that they had dug in the side of the ground. They would translate the fire orders that were coming over the tannoy, move the gun into position, elevate it sideways and then give the order to fire.

Only the ‘Number One’ sergeant would give the order to fire and normally you were ‘Ranging’. This meant that when the first gun was ready, the sergeant would put his hand up (which meant he was ready) and then you would say “Fire!”. The OP would be looking to see where the first round landed and the range would go short or longer.

There was consequently a great competition among the Number Ones to be first to fire and they would watch each other suspiciously.

The other gunner regiment nearby was the New Zealand 16th Field Regiment RNZA and when it was a divisional target that involved more than just our regiment the first gun of all the gunners who said they were the first to say “Fire!” were the New Zealanders who kept coming up first.

There was suspicion among our guys that they were saying ‘Ready’ to show that they were the first. They were brilliant gunners who perhaps wouldn’t take the military discipline that our RSM might expect but as professional gunners they were on the ball.

How long were you at your position at the Hook?

Until the end of the war in July 1953 and then the whole United Nations forces withdrew and we occupied a place five miles back called the Kansas Line.

Can you describe everyday life in the troop on the gun line and your part in it?

It was pretty unpleasant living right on the front line. You can’t move, you’re eating from rations and you’re sleeping in your uniform all the time with boots on. So the OP rotated quite frequently so you could come back for a shower and a beer and things like that. The two officers who were in the gun line would replace them and generally speaking it would be the troop leader (second lieutenant) who would replace him because the gun position officer (lieutenant) was really in charge of making sure that the guns were efficient.

The two officers who were in the gun lines would be ‘one on, one off’ so you would do 12 hours on the line and 12 hours off. But when there was a lot of firing going on you would both be on of course with your four to five gunners who would be in the command post with you. So it was a matter of being at the gun position and carrying out fire orders or rotating up to the OP with the infantry.

What was your rate of fire at the Hook?

It was pretty constant and the Chinese were very aggressive. They kept attacking and we had a thing called a ‘DFSOS’. When the guns weren’t firing they were always on a particular position. The gunner OP officer would go with the company commander and he would say, “Which is your most vulnerable place?” in the entry leading up to the company position. He would call that ‘DF (Defensive Fire) SOS’ so when the guns weren’t firing they would always be laid on the DFSOS. This meant that if there was an attack during the night for example he would shout “DFSOS! BANG!” and the guns would be immediately firing.

If they weren’t laid on the DFSOS there was constant activity. All the battalions and companies were continually doing either standing patrols, which were patrols that would go out fairly close to our wire to stop anything coming or a fighting patrol, which would go down past the Samichon into the Chinese lines. So every night there were calls for fire on that and at the same time we had a thing called ‘harrassing fire’. At night two guns from each troop in turn would go right forward in front much closer to the front line because there would be targets. We would have aircraft flying over and they would see movement well back and also the Americans had capability for what was going on behind where the Chinese would be resupplying.

Like what happened in WWI and WWII there were harassing fire tasks so you would take the two guns right up forward and you’d be given a series of targets. If you fired at a place at two o’clock, you’d fire at another place at ten past and so on just in the hope that you’d knock off the resupply train etc.

The Korean War became infamous for the extremely cold fighting conditions that soldiers fought in. What are your memories of the winter of 1952-53 at the Hook?

I always remember the winter through those harassing fire tasks. The gun numbers used to laugh of course because they were always having to be out and we were in ‘the warm’ but it wasn’t quite like that. We had a paraffin stove and when you went out you would have coffee or tea that would be scalding hot. When you put it down you would give your fire orders, which would take about two or three minutes, and it would have frozen solid!

The guns also had to be moved all the time because they would freeze into the ground. The gunners would have to keep moving them through the night so that they could be moved. When the Argylls and Middlesex arrived [in Korea] they were in their summer kit but by the time we arrived in 1952 we had proper kit so that was a big, big plus. I had a big parka coat and there were fleeces, proper boots, muffs, hats and gloves.

On the other hand, the summer was delightful, Korea is a beautiful place. In the summer and spring there are flowers and shrubs and it was very pleasant “shirts off” weather but the winter was pretty brutal.

THIRD BATTLE OF THE HOOK

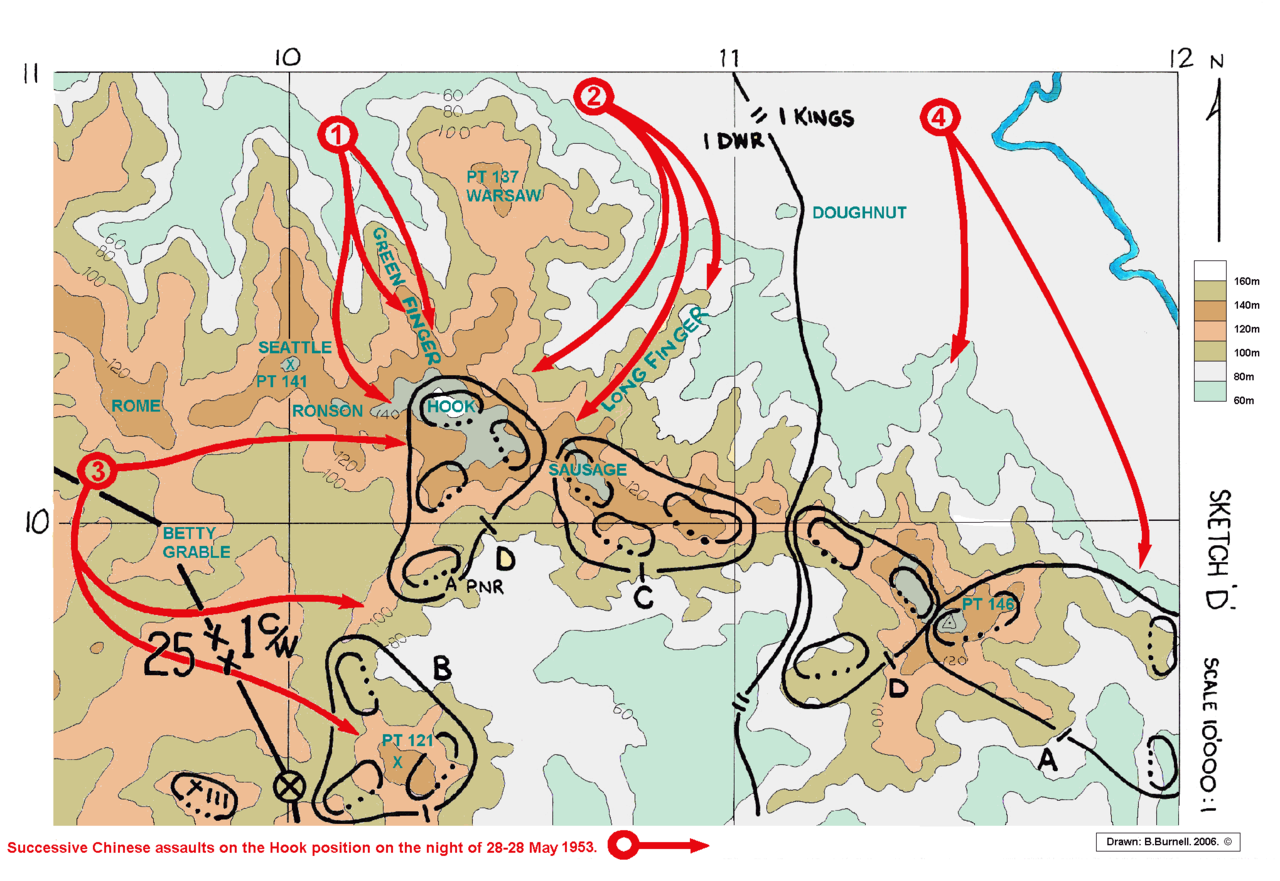

How would you describe what the Third Battle of the Hook (28-29 May 1953) was about?

If you look at a photograph you’ll see that there is a range of hills, the River Samichon and another range of hills. On the left flank of our area was a spur, which overlooked the whole of the valley. This was a period where, although the peace talks were going on, the Chinese and ourselves in various places on the front wanted to get tactical positions so that if fighting started again they would be in a better tactical position.

It wasn’t a strategic battle, there was no ‘breakthrough’ going up to the Yalu or anything but if fighting started again there were certain areas that were vulnerable. The Chinese had decided that the Hook was a place they’d like to occupy tactically for the advantage of it so they threw in three attacks to take this particular feature.

Can you describe your experiences during the battle with Baker Troop?

We knew the battle was going to happen because a Chinese prisoner had been picked up who was brilliant. He knew everything about where he was going and what his signals were. It was far more than a British soldier would know in the plan but he didn’t know the timing . There were all the intelligence indicators that it was going to happen but it was just a question of when.

The Dukes (Duke of Wellington’s Regiment) had time to prepare but it was still pretty much First World War stuff because there were little trenches and hooches.

When the Chinese did attack that night I was at the gun end and a lot of the ammunition (which often wasn’t very good because it was pretty old) was rationed. Generally speaking, each target was given three rounds of gunfire, that was the standard. If an attack went on there would be a repeat but the basic was three rounds gunfire.

On that night it was, “Three rounds, Fire! Three rounds, Fire! Repeat, Fire!” From a gunners point of view it was wonderful, it was a constant, “BANG! BANG! BANG!” Baker Four [gun pit] fired over 600 rounds during the battle. The gun barrel became red-hot and the RASC (Royal Army Service Corps) were splendid bringing up more ammunition.

A friend of mine from Sandhurst was also in the RASC. He jumped out of his cab and involved himself personally by joining in and sending the ammunition up to us. He jumped out, saw the red-hot barrel, took his green army towel out, dipped it in water and threw it over the barrel to cool it down, which was a nice thing to do. The trouble was the towel burst into flames! Several weeks later we invited him up to the mess and gave him a new towel and bottle of sherry!

From that night it was a gunners dream but we lost two of our guys from 45 Battery next door in the OP because the Chinese came in just like the First World War with hand-to-hand combat, grenades and machine guns. We found them with wounds in their back because they had been doing what gunners should be doing, which was looking out of the slit directing fire.

What impact does that experience have on you?

Those two men didn’t make much of an impact on me because they were from a different battery. I knew them briefly but the two that were lost from Baker Troop were my troop commander and Bombardier Alder and that has stayed with me.

What was the idea behind the attack on the ‘Warsaw Caves’ against the Chinese during the battle?

I wouldn’t dream of saying that the artillery were decisive during the battle but undoubtedly the Chinese were very brave. Any thought that they were drunk or on drugs is a misconception. Its good propaganda but it simply wasn’t true.

There’s no doubt that those Chinese soldiers genuinely believed that they were liberating Korea from American occupation and were very brave. To attack up the Hook from their own position they were exposed and terribly vulnerable. We were firing shells that were exploding in the air and splattering down splinters which were devastating if you were in the open. As the Dukes said afterwards, the artillery was tremendous because they were firing on us and our gunner got an MC fighting with them for ordering the fire virtually on top of them.

The Chinese, who were clever, decided to reduce the distance between when they got out of their trenches and reaching our wire and were building a series of caves every night much closer to our front line. This was so that when they did attack their vulnerable distance was much reduced. Photographs showed them digging these caves but they were on the reverse slope so our shells would go over the top. Even our mortars wouldn’t do and the Chinese were even protected from air attack.

It was decided to send a company attack at night out of our wire along the Samichon with sappers and charges to blow up the caves in order to prevent them being used for attack purposes. That was the aim of the Warsaw Cave attack.

Can you describe the attack on the Warsaw Caves?

My battery commander said I would be the FOO (Forward Observation Officer) with the company, which I was very tickled about. I went up the afternoon before the attack and met the company commander and discussed a fire plan and what the route was. I then went down to register the targets. A guy in the Black Watch took me down through our front line and wire to a good place I could see and I then registered targets. I didn’t have to give a grid reference, all I had to do was just say, “Target 174” or whatever it was and the guns knew what that was.

Before the attack I picked the two gunners who would come with me and rehearsed what we were going to do. Unlike communications now the wireless set was a great heavy thing with big batteries so I had a coaxial between my microphone to my gunner who was carrying the radio and batteries on his back while the other guy was carrying reserve batteries. We had a little rehearsal about how it was going to be done and when we were ready we went up for when the fighting patrol and the attack started.

What happened during the patrol itself?

We successfully got down through our wire and went along in the dark. There was a great scare at one moment when a deer ran across out of the darkness. Everybody wet their knickers but then someone trod on a mine and the Chinese lights went up with incoming fire.

My role was to stay with the company commander to order the fire and that’s when a Kingsman (soldier of the King’s Regiment) or part of his team trod on a jumping mine. When you tread on it and take your foot off it springs up. I didn’t know it at the time but two or three men were killed and I was knocked over. But I went on with the company commander and by that time there was a lot of firing and noise. My commander correctly decided to concentrate on one set of caves so he pointed to one of the platoon commanders and the sappers and they went up into the first cave.

There was a big fire-fight and they pushed the charges into the caves. We’d got Bren and Sten guns and the Chinese had Burp guns and hand grenades. They successfully blew up the caves and then we pulled back but the second lieutenant who threw the hand grenades in was wounded. Another guy was also wounded but he stayed back looking after him while we moved back. There was a lot of firing going on now and a troop of tanks came out from our lines and gave us supporting fire. We walked backed carrying stretchers and things like that but the system worked.

Fire from my battery commander brought down fire on the hill all around us so there was continuous firing and the tanks gave us support. It was mission accomplished really.

Were you wounded when the mine detonated?

I actually only found this out a few months ago. I was standing there in the dark and then “BANG!” I was lying on the ground. I went on and joined the company commander and knew I could feel something wet on my legs but I really didn’t know what had happened. It was only months ago that I found an account that said that a guy in this group trod on a mine that killed him and two other guys. All I knew at the time was being in absolute darkness, “BANG!” and then I was on the ground. I was wounded in the leg and knew something had happened.

How did the battle end for you?

I was helped back and popped straight into a Jeep with stretchers on back to the MO (Medical Officer) who pumped morphine and things in and then I basically woke up in the M*A*S*H.

What was the outcome of the Third Battle of the Hook?

It achieved success and we kept the hill. The Chinese wanted it and in the end the ceasefire came and they hadn’t got it. That was down to the bravery of the Black Watch, the Kings, the Dukes etc.

HOSPITAL

Was your time in hospital similar to the famous film and TV series M*A*S*H?

It was absolutely similar to M*A*S*H. It’s the ambiance of that programme. When I see it I think, “Yeah, that’s it!” but I certainly never met ‘Hot Lips’!

However, the thing that struck me was that when I was in hospital there was a young officer opposite to me from the Dukes and he’d been hit. The shrapnel had gone through one cheek, missed his tongue and exited through the other cheek. He wasn’t a happy bunny but there was a nurse there and I remember her saying to him, “You’re lucky. You’re going to have wonderful dimples and the girls will love you!”

I was in hospital for three or four weeks because in the M*A*S*H you went to a hospital in Seoul and then you went to a convalescent place before you went back to the OP.

It was a salutary lesson that its not all glory when you’re seeing other wounded chaps. I was lightly wounded compared to all the others there.

Afterwards, I went back to the OP and suddenly there was a ‘Crack!’ and direct fire from the Chinese hit to the left of the OP. It was only small but it went “Crack!” you realised that this gun was firing right at your slit.

There was then a “Crack!” on the other side and at the same time the forward platoon came up on the air and said, “What the hell are you doing?” This was because the trench had been blown down behind me and as I only had a small OP party some gunners had been sent up to clear the trench and they were throwing it over. The forward platoon could see the trench and so could the Chinese.

Because I’d been in the M*A*S*H, a gunner called Page knocked the aerial down, which meant that we would be of no value at all because we had no aerial. He said, “Shall we go up and mend it?” and I said, “No, we’ll wait a bit.” My troop commander had been killed trying to do that very thing. I suppose I can comfort myself to say that if there had been an attack going on I would have had to do it but as it was it no great dramatic thing I didn’t.

What was the situation like when you returned to the front line?

The situation was the same. There was patrolling, Chinese probing, we did fighting and standing patrols and it was much the same. We were continuing the static warfare.

ARMISTICE

What happened when you inadvertently ordered the entire UN artillery to fire on two Chinese soldiers just before the Armistice was declared?

On the day before the alleged-as we thought-ceasefire there was an incident when I was in the OP looking down into the Samichon and I saw two Chinese guys with white hats laying lines. It was a quiet day but the war was still going on and I thought, “Well, why not?” I got three rounds of gunfire from the troop and said, “Troop target” from our four guns. The battery has a command post over the OP that combined the two troops Able and Baker and to my surprise the commander said over the air, “Battery target authorised.”

Following this, I decided to add 100 yards in firing distance beyond from where these two guys were. The ammunition wasn’t very good and you kept getting shells dropping short on the infantry and the last thing I wanted was an incident like that. Again, to my surprise the adjutant then came on the phone and said, “Regimental target authorised.” This was the 24 guns of the regiment and that’s when the company commander ran in and said to me, “Whats going on?” This was now a regimental target in front of his company and I said, “I don’t know!”

There were now 24 guns firing at the target that I had picked, which were the two soldiers. But I had now added 400 yards beyond the soldiers so the firing was a long way behind them. They were listening to what I had to say so all I had to do was say, “Add 400 [yards]” but then I heard, “Divisional target authorised.” This included the New Zealanders and Americans etc and I’m adding yet another 400 yards.

There was then a ‘Victor Target’. Every gun in the United Nations that was able to reach that area was now firing. As a second lieutenant I fired more guns than had been fired by the British Army since the crossing of the Rhine on these two guys! However, the fire was now a mile behind these two soldiers and so the place erupted all over the Chinese lines. All the UN guns were firing on these two soldiers but it was a mile beyond them now. The shells would have landed on the Chinese positions.

How many shells were firing in that one moment?

I don’t know. The Americans were always very good at firing but the whole of the front was in smoke and it was the result of Baker Troop firing three rounds! The next day I said, “What was that all about?” I was told that it was the last day of the war and the United Nations had decided to show the Chinese that yes, there was a ceasefire, but if the ceasefire wasn’t operative then the United Nations were prepared to continue the war.

It was a show of force to demonstrate a determination that the ceasefire wasn’t the United Nations surrendering or giving in because no one knew whether the Chinese were going to obey the ceasefire.

How did it feel when the Armistice was declared the next day?

The next day was a very quiet day. The ceasefire was due to start at 10 o’clock and it was strange. It was totally dark on our front line and I was at the OP with the King’s Regiment looking over. The Samichon was dark and what we were looking at was almost satanic. The question all the time was, “Do they [the Chinese] know it’s a ceasefire?”

10 o’clock came and there was nothing but then we heard the thing that we hated which was the “Plop, Plop” of their mortars. With their shells you could hear “Bang!” and it would drop but with a “Plop!” it’s in the air and you don’t know where its going to go. Someone reminded me not long ago that when you had to move from your hole to another in the trenches you’d run for your life listening to the “Plop”. This time we heard the “Plop, plop” and we thought, “Oh bugger, its not going to be a ceasefire.”

But then the whole thing lit up, the Chinese were firing their flares that were red, yellow and white. So they did know it was a ceasefire and at the same time all our guys in front started doing the same firing their flares. It was all illegal of course and there was lots of shouting but then it all went quiet.

Then there was this most evocative thing. When it all went quiet again the Fusiliers and the King’s began to sing ‘There Will Always Be An England’. It was quite emotional and the singing spread along the line before it went quiet again.

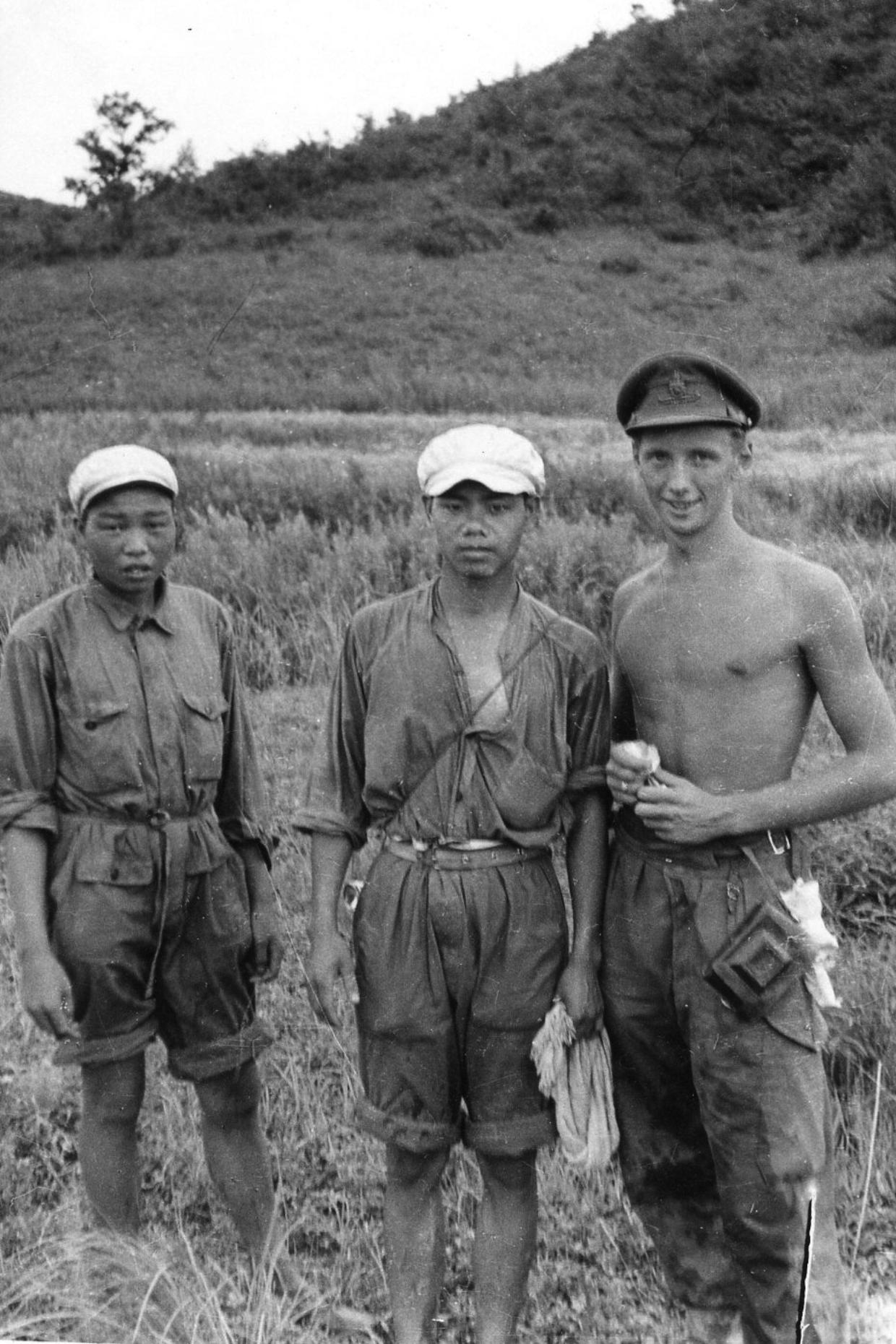

The next day I was sitting having a beer with the platoon commander and he said, “Right, lets go down into the valley.” I said, “No I don’t do that, I’m a gunner” but he said, “Oh, come on!” So we went down into the valley into the bush and walked around it. Then what do we see? The two Chinese soldiers: the ones that we had been firing at trying to kill!

The four of us stopped and we checked to see that they were carrying weapons. They saw that we weren’t carrying weapons and we saw that they weren’t carrying weapons so it became cigarettes and smiles! I had my little camera and took a picture.

The moral of it is that soldiers don’t start wars, politicians say you’re at war. One afternoon I was trying to kill them and they were trying to kill us but 24 hours later here we were having cigarettes and smiling. The Chinese guys were grinning, smiling, having cigarettes and we got on with them. We were just four ordinary guys and it was like Christmas 1914.

When soldiers meet its interesting. Throughout wars you constantly find that when chaps take a prisoner they give them a cigarette 99 percent of the time. The brutality comes from the guys in the back who have a perception about the enemy whereas the chap on the front line thinks, “They’re poor buggers like us!”

There wasn’t any animosity. I think during WWII, certainly against the Japanese, there was an intense feeling of hatred and enmity about what the Japanese had done and what they did if you became prisoners etc. I wasn’t conscious of that in Korea, I don’t recall any great hatred of the Chinese and that was epitomised by the reaction that night.

What were your tasks when Baker Troops was withdrawn to the ‘Kansas Line’ after the armistice?

The DMZ (De-Militarised Zone) was the line we were on when the war finished. The Kansas Line was about 10 miles back and was just another field that you occupied.

At Pyongyang there were repatriations of POWs. It was agreed that all prisoners would come back although they (the Chinese and North Koreans) retained who they thought were the hard cases until the end. I went up a couple of times to be there when they came back and it was always very emotional. Although they would say, “40 guys are coming back today” it often didn’t happen or you never knew what time they were coming. Then the door would open and they would come through. They were shell-shocked because some of them had been prisoners for four years and they’d been up and down being told it would happen and it didn’t happen. Then suddenly they were free and it was a magic moment for everybody.

I was there one day when the RSM (Regimental Sergeant Major) of the Glosters (Gloucestershire Regiment) who had been at the Imjin River came back. He’d been a prisoner for three or four years I think but he came in with a smart bearing. You immediately felt that he could take a regimental parade as the RSM and he probably did!

What were your impressions of the Korean people during the war?

There would have been a restrictive zone behind us where Korean civilians were not allowed through but we saw them. People did come up to the gun areas individually and of course there were a lot of Koreans working with us helping with digging trenches and bringing up supplies etc. They were an integrated part of the army because we were so short of people.

Did you see refugees during the war?

That had passed. You sensed that people were recovering and that they were going to school, rebuilding their houses and so on. The Koreans are a very versatile people and so they were rapidly recovering into what South Korea is today of course. They were bouncing back.

REFLECTIONS

As a regular officer, what were your thoughts on the National Servicemen who fought in Korea?

They were brilliant. They were young boys aged 19-20 who were thrust from school into bitter weather, a desperate enemy and horrible conditions but the regimental spirit was there. Most of them probably had a father who had been in the war [WWII] in the Welsh Regiment, the Argylls, the Norfolks, the Leicesters, Duke of Wellingtons and Black Watch. The sense of a regiment maintained that spirit. There was no agonising and they just got on with it undramatically. It was just what you expected from a regiment.

How many of your men in Baker Troop would have been National Servicemen?

Towards the end it was about 60 percent. They called up the reservists to start with and that was a great wrench. These guys had had five years in the war and had been released and gone back into civvy street. When they got called up to go back to Korea they were not happy bunnies. A lot of other regulars or National Servicemen were sitting in places like Hong Kong or Bermuda so there was resentment. But once they got to Korea they had that framework of experience. They were good men to have on board but then they went and it was over 60 percent National Servicemen.

Had the reservists volunteered to serve in Korea?

No, they were told to report. At the end of WWII there was a commitment of mandatory five years reserve service so there was a legal commitment for them to go if they were called up.

What was your opinion of the other UN fighting troops from other countries?

The Australians were brilliant. They were always aggressive out there and although they probably wouldn’t suit the discipline of a British sergeant major they were brilliant as fighting soldiers.

The New Zealand gunners were also brilliant. I served with a Thai and French battalion, the Americans and the Turks. There was a general acceptance of standards. It wasn’t heroic or anything like and I had never had any worries at all.

I should say that during the war Baker Troop was my life and when I wasn’t at the guns I was at the OP except when I occasionally went down to get rations or something. Apart from in the OP when the Australians and then the Americans came you didn’t meet all these nationalities.

What were the Americans like?

Gung-ho, much more articulate. Again, the unit we were with were very proud of their time at Iwo Jima and the Pacific. The Americans had the momentum of gallantry at war, which was still there at the time.

What is your opinion of the fighting abilities of the Chinese and North Koreans?

I never met the North Koreans because by the time that we were there they were facing us with Chinese divisions. You have to say that they were brave. Strategically, they had logistic problems but of course we had the air force. That was a tremendous advantage. We certainly didn’t see them as in any way inferior to us both in combat, shelling or artillery fire at all. They were just as dangerous.

How did you come by the title of your war memoir Chinese Hordes and Human Waves?

I put that in because the intelligence in Korea was appalling to start with. An American journalist asked what the strength of the Chinese was and the reply was that there were “hordes” and “waves” of them. The journalist, who had been through WWII, then asked, “How many divisions are there in a ‘horde’?” It was terrible intelligence and mis-appreciation, it was just the perception to start with that were these ‘hordes’ of guys coming.

What are your thoughts on who ‘won’ the Korean War?

If you look at it strategically, each side can claim they ‘won.’ The North Koreans probably lost because they launched an attack across the 38th Parallel on the Yalu. The allied United Nations’ aim was to liberate South Korea and they did. The Chinese aim was to get down and liberate the north, which they did. So in those strategic parameters both sides can claim they won.

The ‘losers’ were arguably the South Koreans but that isn’t really the right word to use. When I drove down to Uijeongbu at the end of the war with a Korean driver there was a demonstration and I asked the driver what it was about. He said, “They’re protesting about the end of the war because you’ll be going home and they’re left with a divided country.” So it’s hard to say in binary form who won or lost the Korean War because it remains how it was. However, strategically, the Chinese and Russians would say they won and we would certainly say that we liberated the south so we won.

Why do you think the war has been so ‘forgotten’?

I think its because it came so soon after the end of WWII. We were still on rationing and there were great privations. There wasn’t a mood of celebration about another war.

You once told a group of school students that you thought the war was worth fighting. Can you expand on that?

I talk to a lot of schools. You’ve only got to look at Korea to compare the north and the south. South Korea is an economic tiger, and their education and hospitals are some of the best in the world. We can naturally say that if we hadn’t gone, look at what the people of the north are suffering now.

How do schoolchildren respond to your talks about your experiences during the Korean War?

I’ve been doing it for a couple of years. They are interested and a significant proportion will say, “Oh, my grandfather was there!” When I talk to the schools it’s the history masters who are interested and their sensible reason is that one section of their A-Level paper is about the Korean War so from their point of view this is a couple of hours talk from a guy who was there.

The students are enthusiastic. The story of that last big fight and the two Chinese soldiers clearly resonates. There is a feeling from them I think that war is stupid and peace is preferable. It chimes with their feelings and I will keep saying to them, “They [the Chinese] are brave and they’re just like us and they were probably told to fight etc.” I also tell them, “Let us hope that it doesn’t happen again.”

What are your thoughts about the current heightened tensions on the Korean Peninsula?

I have a view that is perhaps slightly different to a lot of the commentators. They have a view of Kim Jong-un that he is a “funny little man” who is playing this extraordinary nuclear game. My personal view is that if you look at Korean history there was always a series of invasions. This was In living memory and before they were occupied. The Americans then decided, “Right, we’re going to draw this line across Korea. We’ll occupy the south and the Russians can occupy the north.” The Koreans had no country.

The Americans ran Seoul but the Koreans are a proud, patriotic people with a culture going back centuries. I feel that this is something we haven’t experienced. We haven’t been occupied. I haven’t spoken to any Koreans about this possible thought but I think it may be internally that they’re thinking, “The president of the United States, Putin and the Japanese are listening to us now.”

People will say that what Kim is doing is awful and wicked but in historical terms I can understand the feeling. In terms of what he is doing everyone certainly knows about North Korea now. Everybody in the news is saying, “What is he doing? Why is he doing that?” but there are lots of layers to Korean history.

Is there a sense that Western powers today are out of their depth when it comes to Korea?

The South Koreans are of course enormously worried. If there is a war they are going to be blasted and all the great advances will be prejudiced. As a historian, there is just the thought that this isn’t that unexpected. Countries such as China were always dominated by the West but there are other people who are just as proud of their culture and nationality.

How do you think the current tension will develop?

I think it will pan out unless there is an accident. I don’t think Kim Jong-un is planning to nuke Los Angeles and its like the stalemate in the Cold War. However, if you play with petrol, somebody might light the match. It’s a dangerous situation but let us hope that no one does light a match one way or the other.

Do you think the recent tension will ironically bring a wider awareness about the Korean War and towards veterans like yourself?

Yes. Its only been noticeable relatively recently but people are showing more interest.

What are your final thoughts on the war and the men you fought with?

Now I’m 86 I can’t help thinking that those men were 19 and 20 and look what they lost. I know people say this but I feel it. They lost their whole life, their children, wives, everything. That’s where I’m coming from but people should remember their sacrifice.

These were National Servicemen, they didn’t volunteer to be in the army. If you’re a regular then you do volunteer for these sort of things but these were boys out of school who were told to report to Brecon or Colchester Barracks. They were given a few weeks training and then sent off to Korea but to them where was Korea? Why were they going? It’s a tribute to them and the way they fought.

Brian Parritt is a military historian who is the author of Chinese Hordes and Human Waves. A Personal Perspective of the Korean War 1950-53 and The Intelligencers. British Military Intelligence from the Middle Ages to 1929. Both books are published by Pen and Sword Military. For more information visit: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Images courtesy of Brian Parritt and Pen and Sword Military