The British Civil Wars did not end with the execution of Charles I in 1649 as is commonly supposed. The Stuarts were monarchs of both England and Scotland but the English had not consulted the Scots during Charles’s trial and execution. Consequently, the angered Scots proclaimed Charles’s heir (who was also called Charles) as king. The youthful Charles II then invaded republican England to claim his English throne. However, he was defeated at Worcester on 3 September 1651 by Oliver Cromwell and the New Model Army in a battle that finally ended the Civil Wars.

Although Charles’s subsequent dramatic escape from England is famous, historian Charles Spencer spoke to History of War in support of Warwick Words History Festival about the Battle of Worcester. This decisive clash of arms was one of the most important battles of the age and changed the course of British, and perhaps global, history.

How extensive was Charles II’s military experience before 1651?

We tend to think of Charles II in terms of his being the “Merry Monarch” – an incorrigible pleasure seeker, whether with his mistresses, his courtier “wits”, or with his love of horse racing and rich entertainment. But, during the Civil War, he saw action repeatedly. He was present at the first major engagement, Edgehill, as a 12-year-old – he and his younger brother James, Duke of York (later James II) had to be stopped from joining in a charge at the enemy.

Towards the end of the First Civil War he was sent to the southwest to lead the Royalist forces there. Although he had professional generals with him, he never shirked his military duties. He was witness to rolling defeats that eventually forced him into exile, in 1646. Even then, when the Second Civil War erupted in 1648, Charles led the English fleet that had deserted Parliament and fled to the Netherlands. That summer he was ready to lead his ships in a large scale naval encounter off the English coast when a storm scattered the two fleets. But his officers saw for themselves that he was genuinely keen to get stuck into the action – he absolutely rejected their entreaties to take safety below deck.

What were the differences in quality between Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army and Charles II’s primarily Scottish force during the Worcester Campaign?

The New Model Army was a key factor in turning the tide of the civil wars against the Royalists: It’s soldiers were militarily tough, extremely disciplined (with harsh punishment for any wrongdoing), and filled with the belief that God was on their side. They were ably supported by the militia of various counties, which had New Model Army men added to their ranks in order to raise their level of fighting know how.

Charles’s Scottish army only numbered 16,000 men, led by clan chiefs and leading aristocrats. They were a pitiful sight, and they knew it. Even their artillery consisted only of leather guns, rather than metal ones. It was all very one-sided – made more so by the fact that Cromwell had an advantage of more than two to one.

How did the Battle of Worcester unfold on 3 September 1651?

3 September 1651 was a sparkling day. Charles II looked from a church tower first thing, and saw Cromwell’s vast army deploying pontoon bridges, and advancing in huge numbers. The Parliamentary artillery opened up to announce that battle was underway, then Worcester was assaulted by the New Model Army in two waves.

The main Scottish cavalry unit, numbering 3,000 men under General Leslie, looked at the way the battle was going, and left the field without fighting. Up to 4,000 Royalist soldiers were put to death, while Cromwell lost a few hundred men. There was particular carnage inside the packed streets of Worcester.

In purely military terms how does Cromwell’s victory at Worcester compare to his other battlefield successes?

Worcester was, Cromwell believed, his “crowning glory”. It was the last battle he fought, and it ended Royalist military resistance, and was the third and final act of the civil wars. It was an overwhelming triumph, and was recognised as such. Before it, it was possible that the late king’s son would seize the throne. Afterwards, the republic was solidly established.

Although the results were so far reaching, Cromwell noted that there were several hours on that day when the battle could have gone either way – most of the Royalists resisted with great bravery. While Marston Moor won the north of England, Naseby destroyed Charles I’s main army, and Dunbar was an astonishing turn around, Worcester was the ultimate knockout blow.

How did Charles II conduct himself during the battle?

Charles II was noted for his great personal bravery during the battle. He put himself into the heat of the action, and exhorted his men to fight on. When defeat was inevitable, he shouted out that he would rather be shot than be taken prisoner. Once all was lost, the 21-year-old Charles tried to persuade his generals that they should continue fighting. They – who knew what utter defeat looked like – almost had to drag him away from Worcester.

How did Parliamentary forces treat Royalist prisoners after the battle?

You did not want to be taken prisoner and it was all very brutal. After Worcester there were so many men captured that all the surrounding towns and cities became holding stations while they were processed.

Many were then sent to London – slowly, so that preparations could be made for receiving them. They relied largely on charity for basic food, such as hard biscuit. Thousands of Scots were penned into a prison compound on marshy land at Tothill Fields, outside the capital, where only the wounded could be guaranteed shelter. Many hundreds died there, from exposure and disease. Others were sent in indentured servitude – little better than slavery – to North America, the Caribbean, and to drain the Fens. English observers delighted in saying how bestial the Scottish prisoners were; but, given how they were treated, this is not surprising.

The future US presidents and founding fathers John Adams and Thomas Jefferson visited the battlefield at Worcester in 1786 with Adams describing it as “the ground where Liberty was fought for.” To what extent do you think that is true?

I believe the Battle of Worcester was of such huge importance, that it should be much better remembered by us now than is the case. After it, the extreme, almost feudal, form of kingship that Charles I had beloved was incapable of returning. While the balance between Crown and Parliament was in question until 1688, when James II’s exile during the Glorious Revolution was achieved, Worcester represented the death knell of military force underpinning kingly excess.

Adams and Jefferson could see the clear link between the Parliamentary triumph at Worcester, and the rise of political ideals that underpinned the American constitution.

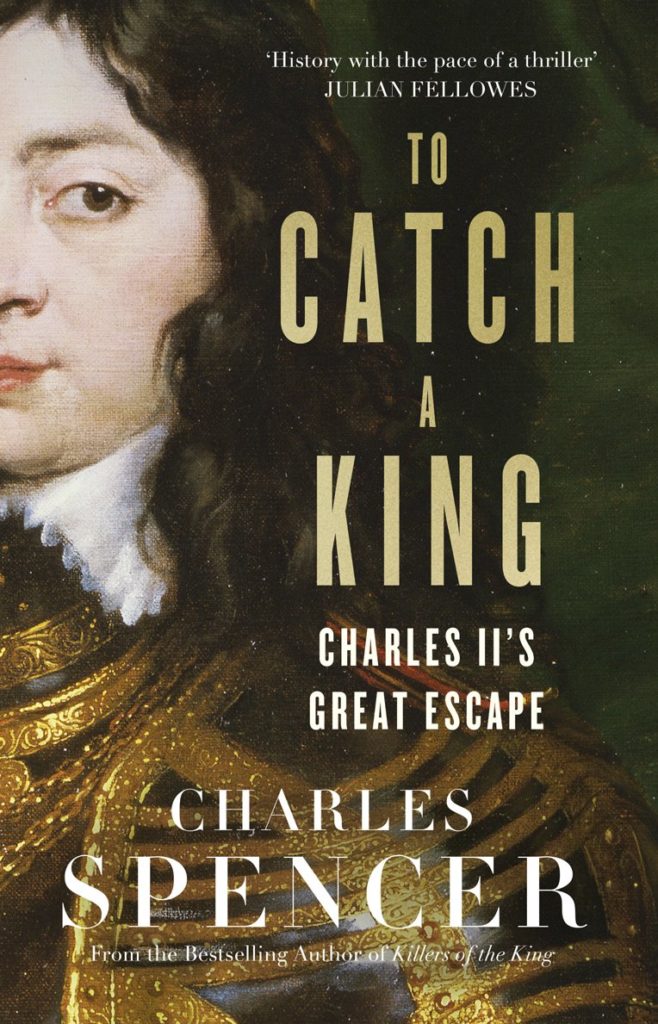

To Catch a King: Charles II’s Great Escape is Charles Spencer’s new account of Charles II’s famous escape from the Battle of Worcester. It is published by HarperCollins and is on sale now. For more details visit: www.harpercollins.co.uk/to-catch-a-king