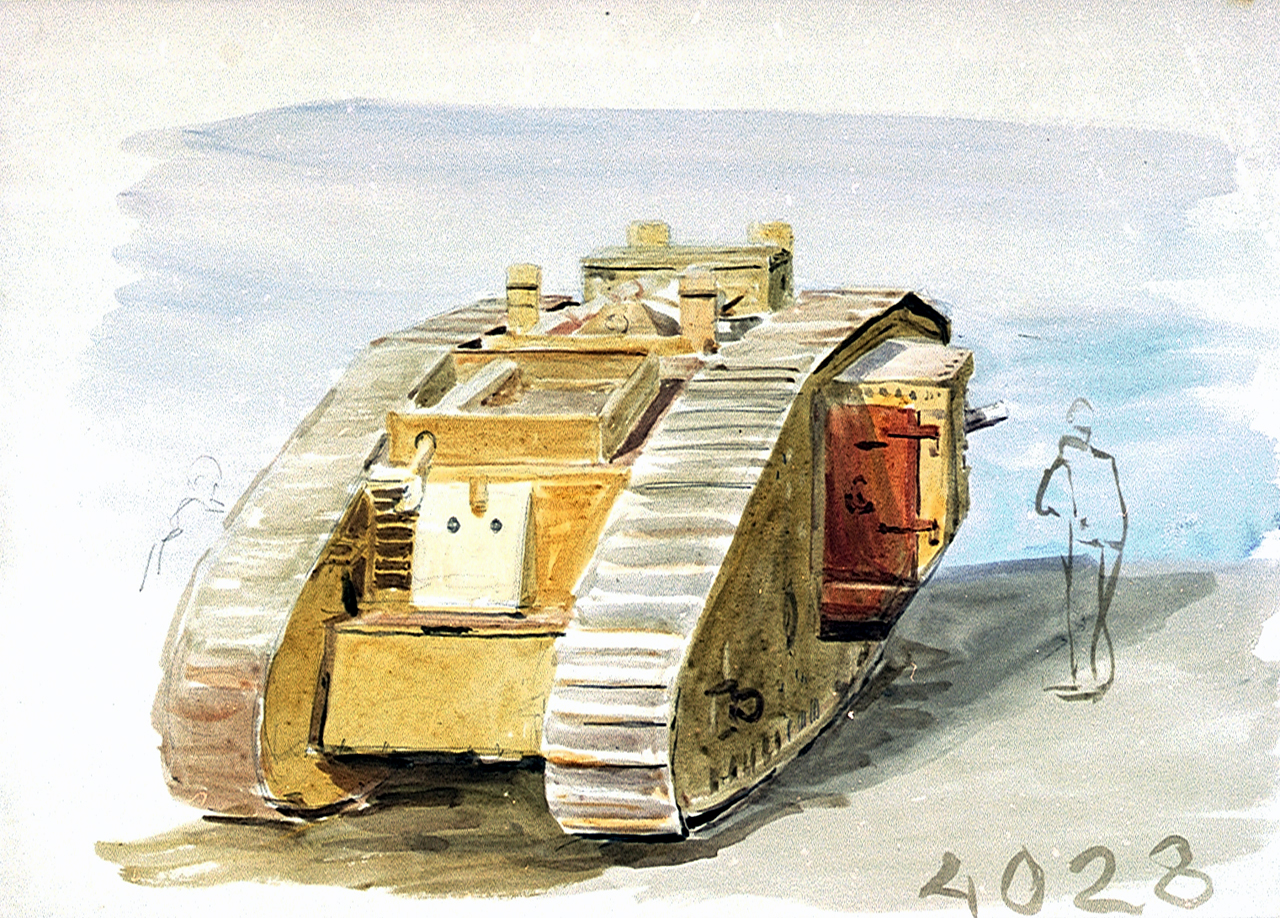

The First World War witnessed a host of technological innovations, but one of the most dramatic made debuted on 15 September 1916. It was on this day, in the middle of the campaign, that the British effectively began armoured warfare with the introduction of the Mark I Tank. Speaking to History of War back in 2016 at the launch of the Somme 100 app with the Royal British Legion, TV historian Dan Snow explains the tanks’ impact on the battle as well as their crews.

What process did the original tanks go through before they were battle-ready in 1916?

The most interesting thing about tanks in 1916 is that [they] went from an idea in the autumn of 1914 of trying to utilise Britain’s advantage in mechanical armoured objects, albeit ones that floated on the water, to somehow using them on land as ‘land-ships’. The fact that it went from the drawing board onto the battlefield in two years is extraordinary.

The story of the tank belies the idea that Britain was traditional and didn’t want to innovate and that the generals were really conservative. Actually, this technology [was] being raced to the front arguably too fast, because there were huge numbers of tank ideas that were tried out. ‘Little Willie’ was successfully tried out in the autumn of 1915 so it [was] a year from a vaguely working prototype to deployment on the battlefield…

Tanks were first used at Flers-Courcelette in September 1916, but what impact did they have on the battlefield at that time?

They didn’t ‘break-through’ but they did ‘break-into’ German positions. Many of them broke down on the way up and many didn’t even cross the British front line. Lots were disabled and they were very slow. Although they could traverse No Man’s Land, German guns could hit them if the gunners were able to see them. So they weren’t a wonder weapon but there were one or two tanks that would get out into a bit of space and it was more the tantalising prospect that was raised by the success of these individual tanks that inspired the BEF to order more.

In many quarters the British public today don’t want to hear good news about Douglas Haig, they don’t want to believe he was anything but a butcher. He actually stuck his neck out [to order] a large number of tanks for use in 1917 and it was those tanks that formed the backbone for the attack at Cambrai in late 1917, which is the first stunning success of armoured vehicles in its history. It probably would not have been possible without their first deployment at Flers-Courcelette. The tanks did just enough there to justify a big order.

WWI was probably the most innovative period in the history of the British Armed Forces and the high commands were reaching for anything that could possibly break this stalemate. They were desperately trying to find alternatives to frontal assaults against fixed infantry positions protected by barbed wire. I think the story of the tank is part of the wider story of innovation in 1916 and on the Western Front.

What was the reaction among the German troops when they saw the tanks coming?

I think it came as a complete surprise, certainly to the frontline infantrymen. Some sources have said that there was an important morale factor in that it spooked the enemy. I’ve talked to a German historian recently and he’s said that the tanks didn’t unduly freak out the Germans. There’s the myth about these steel monsters that just made the enemy run away, which isn’t quite true. I think it was probably patchy in places. If you were in a machine gun nest and there was a tank rumbling towards you you’d probably run away but not because there was some mythical element to the tank.

A new weapon of this kind would probably have boosted British morale, but I don’t think it led to total terror and collapse on the German side as some people have traditionally suggested. The tanks were going so slowly and deliberately that if you had to abandon your position, you would have had plenty of warning to [do so] at your leisure.

How were the tanks able to communicate with one another effectively, as well as with the troops outside?

This is the problem, there’s no radio contact. At this point there was no way of communicating. However, very rapidly they put a bell on the back of the tank so that the infantrymen could go up and ring it. Isn’t that absurd that you have to go up and ring a bell? It’s very amateurish but the trouble is you’ve got a steel box with a big engine roaring inside and you’re locked in for protection. Suddenly communication is a big issue…

Armour-infantry co-operation was extremely difficult and it was not until the Battle of Amiens when they’d spent two years trying to perfect it, that communication got better.

The problem with World War I is that everything is brand new. Aircraft had only been in the sky for a decade, tanks had just burst onto the scene and there was no real way of meshing them all together.

What lessons did tank developers take from the performance of the machines on the battlefield?

Serviceability was a big issue as was crew endurance. How do you make these tanks more comfortable so you don’t asphyxiate the crews, burn them and basically hospitalise them after a day inside them? A big issue was moving them into a position where they are able to attack without alerting the enemy. The engines are very loud so how do you concentrate them in their jumping-off points without alerting the enemy? There are many lessons to be learned. Then, of course, you’ve got a problem when tanks get too isolated so if they do enjoy success and penetrate into German defences you actually end up isolated and not helping the infantry advance.

What is born on the Somme, and continues in armoured warfare right up until the Gulf War in 1991 and beyond, is a debate about how tanks are designed to thrust deep into enemy lines in order to sow chaos and confusion in line with quite conservative goals involving supporting the infantry. You see the very beginnings of that long-running debate in the autumn of 1916.

What were conditions like inside the tanks? Were the drivers well trained before going into combat?

Obviously they weren’t as well trained as they would be later in the war, it was all pretty rushed. The inside of the tanks was absolutely brutal. If you go into one of those tanks there’s no separation between the crew compartment and the engine. The engine is really hot and blasting out appalling fumes and there were real problems with burns. There’s also not much in the way of suspension so you’re being thrown around inside a lot.

There was also ‘blue-on-blue’ sometimes. Officers would have to stand up and give visual cues so that there wasn’t friendly fire. They had to take incoming fire as well. Even machine guns with rounds that were not armour-piercing could make life pretty miserable inside a tank – you’re attracting enemy fire and it’s hammering on the outside of the tank. It’s a brutal, claustrophobic place to be.

Haig wanted 150 tanks for the battle but only 50 were eventually available. Would this full force of tanks have changed the course of the battle much?

I don’t think at that point in their history tanks were a breakthrough weapon. I think the fundamental problem was fuel, range, speed and they were not the strategic weapon they would become in WWII and other conflicts. What’s so remarkable about 1918 is that for the first time you get these light tanks, which are almost like armoured cars, that actually break through German positions and they’re in the ‘green fields beyond’. They actually do things like surprise a German corps commander while he’s having his breakfast and it makes them an extraordinary weapon.

However, I think the Mark I tanks were too limited to be really effective in 1916 but it, obviously, didn’t hurt at the same time and I think they would have proved themselves even more. Because of their unreliability, 150 might have perhaps been a bigger embarrassment to the British. The key thing about the tank is that Haig ordered 1,000 of them after the battle, which was a brave decision. 1,000 tanks is asking a lot of an industry struggling under the pressure of the war, but a seed was laid that began of one of the most prominent features of 20th century warfare. 20 years after their introduction [at] the Somme tanks are thrusting deep into Russia and encircling literally millions of Soviet troops. It’s an amazing journey.

The app Remember the Somme with Dan Snow and The Royal British Legion is available now as a free download. For more on the incredible innovations of World War I, subscribe to History of War for as little as £13.