WWII historian, author and broadcaster James Holland explores the build-up, events and aftermath of the pivotal naval battle of the Pacific War

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

At 10.20am on the morning of 4 June 1942, the United States was losing the war in the Pacific. At 10.27am, it was winning. In those seven minutes everything changed in what was really the American Trafalgar and which saw the Imperial Japanese Fleet annihilated in a spectacular confrontation that was dramatically unexpected. It’s an incredible story and it’s no wonder it has become the subject of a new movie.

When the Japanese entered the war with their assault on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on the morning of 7 December 1941, it’s important to understand what it was they were trying to achieve. There was certainly no grand plan to conquer the United States and take over the White House. Rather, it was about creating time; the idea was to cripple the US in a dramatic single strike to buy them perhaps six months or more – time in which they would conquer the resource base they would need to continue their war in China.

By the 1930s, Japan was rapidly modernising, its cities growing, and yet it did not have the resources or access to resources to support this growth. China, on the other hand, most certainly did, and so its increasingly nationalistic and militaristic leadership invaded in 1937. It did not all go to plan, however, and they soon became bogged down in an attritional conflict that quickly began to cost them a lot more than they were gaining.

All around south-east Asia, however, were all the resources they needed, but these territories were owned by the British, the Dutch and the Americans. Already, in 1940, following the fall of France to the Germans, the Japanese moved into French Indochina (now Vietnam), a strike that greatly unsettled the western powers. Most of Japan’s oil and steel was provided by the USA, who responded to Japanese aggression by making it far harder for them to continue buying these essential goods. This put Japan in a difficult position. Either they had to back down, pull out of Indochina and even China with the loss of face and economic catastrophe that would entail, or come up with an alternative plan to get them out of the mire. When Prime Minister Konoe resigned in November 1941 and Hideki Tojo took over, the die was cast. Tojo was an ultra-nationalist and hawk who believed that for all America’s might and wealth, culturally, the USA did not have the stomach for a fight. The Japanese might have been materially weak, but they did have a modern, highly trained navy. Mentally and psychologically, they also believed they were superior. And so the idea of a strike on Pearl Harbor was born – a daring attack that would knock out the US Pacific Fleet in one blow and buy them a precious commodity: time.

Pearl Harbor was the brainchild of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, a highly cultured man who had studied in the USA and who was opposed to Japan going to war. However, he believed this gambler’s throw of the dice was the only way in which Japan could solve the conundrum in which they found themselves. It was daring, it was bold, but it was also flawed because back on 27 November 1941, Admiral Husband Kimmel, commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet on Hawaii, was warned by Washington that war with Japan might break out any moment. Kimmel responded by sending two of his four aircraft carriers out of Pearl Harbor and to the Pacific outposts of Midway and Wake, two small atolls turned into military bases. A third carrier was undergoing a refit and the fourth was serving in the Atlantic.

The Japanese attacking Pearl Harbor caused untold damage: 353 aircraft operating from their own carriers achieved total surprise, their torpedo bombers crippling the US Pacific Fleet while dive-bombers hammered the island’s airfield. Within minutes all eight battleships had been hit. A further 171 aircraft in the second wave roared in to attack a short while later, so that where once there had been ‘Battleship Row’ there was now a mass of twisted metal, angry flames and billowing thick smoke. And a lot of dead American servicemen. On the airfields, 188 aircraft were destroyed and a further 159 damaged. Also hit were three cruisers, three destroyers and three other vessels.

Pearl Harbor was seen as a terrific success in Japan, although not by Yamamoto, who was hugely disappointed. He understood that a shift had taken place in naval warfare – that battleships were no longer the pre-eminent warship but rather, that mantle had been passed to aircraft carriers, and for all Pearl Harbor’s success, not one American carrier had been hit. Yamamoto understood that his navy simply had to destroy those carriers, and so immediately began planning how he might get them, and Midway, he believed, held the key. He would not target the tiny Midway atoll for invasion, but rather, use it as bait. By threatening this vital US base, the Americans, he hoped, would be forced to defend it and send their carriers. And when they did, his superior force would pounce and destroy them.

First, though, the Japanese Army, supported by the Navy, had to consolidate its own position in the Pacific and South East Asia. Malaya, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies, Burma and the US Philippines were all overrun in an astonishing series of rapid and extremely violent strikes. The ABDA command – American, British, Dutch and Australian – was both underprepared and caught off guard and had no answer, but while the Japanese might have appeared unstoppable the threat from the rapidly growing US armed forces, and especially its navy, had in no way gone away.

Meanwhile, the US was also planning how to strike back. American strategy in the Pacific was led by Admiral Ernest King, the Head of the US Navy. His approach was clear and based around two fundamental factors: first, Hawaii could not be allowed to fall, and second, nor could Australia. He ordered Admiral Chester Nimitz, who had replaced Kimmel, to make his first priority to secure the seaways between Hawaii and the island of Midway, just to the east of the international dateline, and the North American mainland. His second priority was to make safe the routes to Australia. Fiji and the Samoan and Tonga Islands needed to be made secure as crucial strong points along the way, and from these bases a counter-offensive could be then launched. It was unquestionably the right strategy.

On 1 February, the US Navy’s fightback got underway with a series of raids on shipping and airfields on the Japanese-held Marshall Islands, although the material damage was less than had at first been thought, it had taught the Americans vital lessons and got the fightback underway.

In April 1942, they launched the Doolittle Raid, flying sixteen B-25 bombers from the carrier USS Hornet and bombing ten different targets on Japan, including Tokyo. While the physical damage was small, the psychological impact was huge as it made the Japanese realise they were not impervious to attack themselves. It also ensured the Japanese Army, which was a ferocious rival of the Navy, now agreed to support Yamamoto’s plan to lure the Americans at Midway.

Further US carrier raids were mounted but the first major naval clash came in May 1942. The Japanese now planned to disrupt Allied plans by invading and occupying Port Moresby in New Guinea, to the north of Australia, and also the island of Tulagi in the Solomons. Crucially, American cryptanalysts had broken Japanese codes, however, and learning of the plan, a joint US-Australian naval force of carriers and cruisers was sent to intercept and stop the enemy’s plans. Tulagi was invaded on 3-4 May, but the Japanese had been surprised to come under attack by American aircraft from the carrier Yorktown. They now advanced to meet the Allied naval forces, clashing in the Coral Sea on 7 May.

This was the first battle in which aircraft carriers engaged one another, and both the Americans and Japanese lost one each and suffered damage to the others. On 8 May, US radar screens picked up enemy aircraft heading towards USS Lexington and Task Force 17, and her Wildcat fighters were scrambled to meet them. Then, at 11.13am, lookouts spotted the black dots of enemy aircraft. As they approached, the attacking torpedo bombers split into two groups while enemy dive-bombers peeled over and down towards the Lexington, which was now frantically taking swerving evasive action. The enemy planes met a wall of anti-aircraft fire as well as the Wildcats. ‘It seemed impossible we could survive our bombing and torpedo runs,’ said Lieutenant Commander Shigekazu Shimazaki, the Japanese attack commander. ‘Our Zeroes and enemy Wildcats spun, dove, and climbed in the midst of our formations. Burning and shattered planes of both sides plunged from the skies.’

Despite the heroic defence, Lexington was hit by both bombs and torpedoes, but amazingly, fire-damage parties managed to restore her to sea-going order before a series of explosions ensured the mighty carrier would have to be abandoned and scuttled. With both sides suffering heavy losses of aircraft as well as ships, the battle ended as dusk fell on the second day of battle. Crucially, the Battle of the Coral Sea ensured the Japanese abandoned their plans to invade New Guinea.

Admiral Yamamoto is rightly feted as an inspirational and enlightened commander, but his plan for Midway was too complicated at a time when it did not need to be. At this stage of the war, they had both quantitative and qualitative superiority over the Americans: their torpedo bombers were better, their pilots better trained and they had more warships than the Americans. It would not last, as Yamamoto was well aware, which was why Midway presented a golden opportunity to set the US Navy back not just six months but potentially much longer. In the intervening time, the Japanese could further extend their defensive ring. With luck, Yamamoto hoped the Americans would then sue for peace and the Japanese would be left alone, now resource-rich and able to finish a victorious war with China.

His plan was to entice the US Pacific Fleet into battle by separating his forces, with his carriers and battleships several hundred miles apart. The plan was to attack the enemy carriers and then follow up with his battleships and cruisers, who would then engage whatever American ships remained.

Just as Japanese intelligence was poor, however, US intelligence was excellent. American code-breakers had intercepted and cracked enough Japanese naval signal traffic to give them a picture of what the enemy was up to. It was Admiral Nimitz’s responsibility to interpret this intelligence picture and work out what to do about it. He knew the Japanese had four or five carriers and that he had three. On the other hand, he could use the airfield of Midway as an unsinkable carrier, which potentially evened it up. Even so, his decision to take on the Japanese was a huge one and massive risk, albeit a carefully calculated one.

It was perhaps more so because his main carrier task force admiral, Bill Halsey, was sick, which left him short of a carrier commander. He filled the post with Admiral Ray Spruance, who was hugely competent but whose experience lay with commanding cruisers, not carriers. Spruance was appointed at the last minute and headed out to take command of Halsey’s two carriers in what was unquestionably going to prove a decisive clash against the Japanese. Admiral Jack Fletcher was overall US commander at sea.

The clash began on 4 June with the Japanese sending the carrier air forces to attack Midway. Because they had no idea the Americans had cracked their codes, they had been expecting to catch the US air forces napping on the atoll, but in fact, the American bomber force had already taken off to attack the Japanese carriers. Yet the first American air strike on the Japanese carriers was a disaster. US naval air forces – a combination of heavy bombers and torpedo bombers – were arriving from Midway at different times rather than as a concentrated mass. Japanese naval fighters were scrambled and because of their superior skill and capabilities, picked them off with ease. The American torpedo bombers missed entirely and were largely slaughtered. Then the B-17 heavy bombers from Midway arrived, but were too high, too inaccurate, and although from 20,000 feet up the carriers below had disappeared behind huge fountains of water, not one had been hit.

At this point, the Japanese were unquestionably winning the battle and with it, the war in the Pacific. It was, though, now time for the US carriers to launch their strike force. Radio intelligence reaching the carriers suggested a location for two of the Japanese carriers but not the remaining pair. All three US carriers were now ordered to send in their own aircraft to attack the Japanese, but the commander of the USS Hornet ordered his men to head in a different direction to look for the missing enemy carriers. It was a hunch, and, as it turned out, an entirely wrong one too. This meant that with the Midway air forces effectively destroyed, and Hornet’s force heading in the wrong direction, the US now had only two carriers against four Japanese – and so dramatically slashing the odds of success.

The trouble was, those aircraft could not find the Japanese either, and fuel was starting to get a bit low. Commanding the dive-bombing squadrons from the USS Enterprise was Lieutenant—Commander Wade McClusky, with a further squadron from the Yorktown. McClusky was determined not to turn for home without having spotted the Japanese carrier fleet. His courage paid off because in the nick of time, he spotted the wake of a Japanese destroyer going at speed and realised it had to be trying to rejoin the main force. Ordering his men to head in the direction the destroyer was steaming, sure enough, at 10.22am they spotted the Japanese carriers. And there weren’t two of them, but all four.

Ahead of McClusky’s bombers, however, were one squadron of torpedo bombers from Hornet, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander Jack Waldron, who had disobeyed the orders and flown his men towards where he believed the enemy carriers would be. He had been quite right but was about to pay a terrible price. Once again, Japanese naval fighters and gunners on board the ships made mincemeat of the American torpedo bombers, and all fifteen were shot down; Waldron was among those killed.

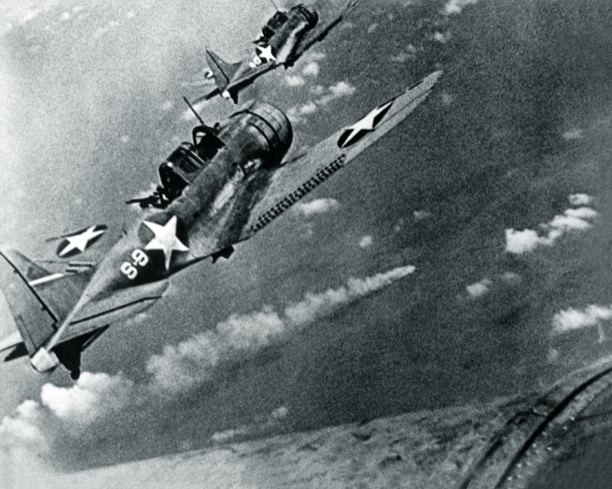

Yet the sacrifice of the torpedo squadron gave a glimmer of hope to the bombers, because with the Japanese fighters focusing on the torpedo squadron as they attacked at low level, the McClusky’s thirty dive-bombers as well as the fifteen from Yorktown were left alone. Despite anti-aircraft fire, the Dauntless SBD-2 dive-bombers now had a fairly clear run. The two squadrons from Enterprise were ordered by McClusky to split into two and attack two of the Japanese carriers at the same time, but through a miscommunication, all thirty began diving towards Kaga. Realising the mistake, Lieutenant Dick Best and two of his wingmen, swung north to attack Akagi. Meanwhile, Kaga was struck between four and five times, with one bomb hitting near the bridge and killing the carrier’s commander and senior officers.

A few minutes later, Best and his wingmen were diving on Akagi. Although only hit once, and by Best, it was a fatal strike as it penetrated the deck into the main hanger causing a massive explosion and fires. Another bomb had damaged the rudder.

Two aircraft carriers had been destroyed in a matter of minutes and now it was the turn of Yorktown’s dive-bombers, commanded by Max Leslie, this time targeting Soryu, and hit it three times. Three carriers had been stopped dead in the water, their aircraft destroyed and each one now floating infernos. The fourth carrier managed to survive the onslaught and soon after launched a counter-attack, hitting and crippling the Yorktown. Later that afternoon, however, after a scout plane from Yorktown located the final carrier, Hiryu, the dive-bombers of Enterprise took off again, found the fourth carrier, and hit the ship four or five times, including a second bomb from Dick Best.

The Japanese abandoned ship and then scuttled the Hiryu, although Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi and the ship’s captain, Tomeo Kaku, decided to remain on board and go down with the vessel. This act of seppuku robbed the Japanese of their best carrier commander.

Although the loss of Hiryu was a terrible further blow for the Japanese, in truth the battle, and arguably the entire Pacific War, had been won in those seven minutes between 10.20am and 10.27. It had been an astonishing victory by the Americans, who, without doubt, had begun the day as the underdogs. On that one June day, however, Japanese hopes of further consolidation in the Pacific were dashed for ever, their one chance to halt the Americans lost.

And just two years later, the US Navy attacked the Japanese island of Saipan with a staggering twenty-four carriers. Its moment of weakness had been in the initial six months of war, but at Midway, good fortune, brilliant intelligence and bare-faced courage had conspired with Japanese hubris to bring about surely the greatest victory at sea in American history. The Japanese failure at Midway was one for which they would pay dearly.

Opening image copyright Lionsgate 2020

MIDWAY is out now on Digital Download, and on 4K Ultra HD, Blu-ray and DVD 9th March