In 1941 Viktor Ullmann was a rising star among Prague’s numerous young and talented composers. A student of Arnold Schoenberg and, later, Alexander von Zemlinsky, Ullmann had a good job as conductor at one of Prague’s opera houses and had enough financial security to self-publish several of his own works. He was the son of an Austrian army officer whose Jewish heritage had not prevented him from being raised to noble rank by the Austrian government because of heroic service in World War I. The family had been stationed so long in Czech Silesia that Viktor considered himself Czech, even though German was his first language.

But in September 1942, Ullmann’s Jewish ancestry resulted in his arrest and deportation to Theresienstadt. However, even if he were not Jewish, it is still possible that Ullmann could have been deported based on his membership in the Anthroposophical Society, which had been founded by Rudolph Steiner in 1913. Steiner was a successful Viennese architect and philosopher whose Waldorf Schools had become popular throughout Europe and America and whose views, and followers alike, were hated by Hitler.

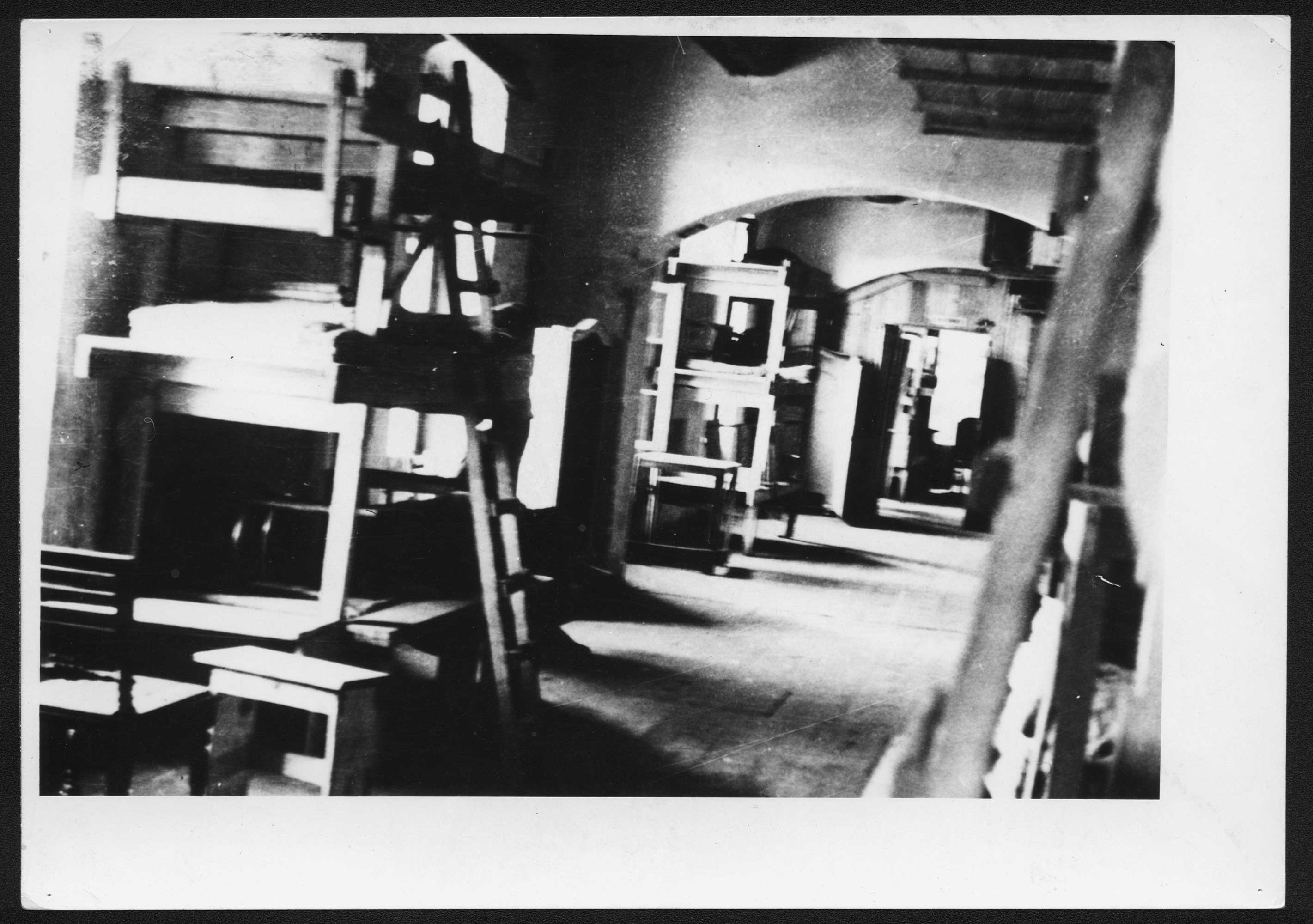

Upon arrival in Theresienstadt, Ullmann realised that the many musical activities organised by fellow prisoners Raphael Schaechter, Gideon Klein, Karel Ancerl and others were focusing either on works from the standard repertoire or folk songs that could be arranged for various vocal groups – from children to adults. He also realised that many of Europe’s finest musicians were being incarcerated in Theresienstadt. He therefore immediately sought permission from the Jewish Council of Elders to start the “Studio for New Music” which performed art songs and chamber music by composers such as Gustav Mahler, Bruno Walter, Alexander von Zemlinsky, Alois Haba and himself. He also encouraged composers already in Theresienstadt – Gideon Klein, Hans Krasa, Pavel Haas and others – to compose new works that could be performed only by the finest musicians. Ullmann himself contributed numerous art songs, three piano sonatas (his 5th, 6th and 7th), a string quartet (his 3rd) and, with fellow inmate Petr Kien as librettist, the opera “Der Kaiser von Atlantis.”

Among Viktor Ullmann’s greatest contributions to life in Theresienstadt were his regular articles on the philosophy of music (especially regarding conditions in Theresienstadt) as well as reviews of concerts and other musical and theatrical productions. These were originally published in “Vedem” (“In the Lead”), a secret weekly publication produced by the boys in Barracks 417. Music making in the Nazi concentration camps and ghettos was often controversial and in Ullmann’s most famous essay, Goethe and the Ghetto, he came down squarely on the side of those who endeavoured still to create. In a defiant and scathing reference to Psalm 138 he wrote:

“In Theresienstadt . . . by no means did we hang our harps by the rivers of Babylon and weep . . .”

Still, Ullmann realised that music was also needed for the children and other inmates who were, perhaps, less musically sophisticated than others. He therefore arranged ten Hebrew and Yiddish folksongs, two for male voices, three for children, three for women’s voices and two for mixed voices. But where did Viktor Ullmann find these songs? He was totally assimilated into secular Austro/Czech culture and knew nothing – absolutely nothing! – about being Jewish. Further, he spoke neither Hebrew nor Yiddish.

The answer most likely lies in the Makkabe Lieder Buch a Zionist songbook published in Berlin in 1931. There is a copy in the Theresienstadt town library. It is not known if this songbook was brought to Theresienstadt by a deportee or if it was already in the library in 1941 when the Nazis turned this little town of 5,000 into a concentration camp of 40,000. Nevertheless, the songs in the book appear in the same keys and with the same German transliterations of Hebrew and Yiddish as Ullmann’s arrangements.

The two songs Ullmann chose to arrange for mixed choir are particularly interesting. The first, Eliahu Hanavi, is sung towards the end of every Sabbath morning service. It is a prayer for the Prophet Elijah to return and herald redemption. In Ullmann’s version, the petitions become more of a demand. The second song, Anu Olim Artza is a Zionist song of hope: “We are going up to the Land with song!” Today in Israel this song is sung with updated words: Anu Banu Artza: “We have come up to the Land!” In Ullmann’s arrangement, the senses of urgency and aspiration are highlighted by a tempo that gradually gets faster and faster, so that by the end the music almost explodes. These two songs, and other vocal music from the Holocaust (including Mozart and Mendelssohn!), will be performed on the Pure Land Series at The China Exchange on Thursday evening, 4 May 2017.

| Pure Land Series has the pleasure of presenting Dr Nick Strimple and Singing in the Lion’s Mouth: Music and the Holocaust, 1933-2016 at the China Exchange on Thursday 4th May 2017.

The Pure Land Series at China Exchange invites inspirational speakers and like-minded people to share their visions of a world grounded in compassion, empowerment, spirituality and creativity. The series is hosted by the Pure Land Foundation, supporting charitable endeavours to promote social, spiritual and emotional wellness. It also aims to enrich lives through art and music. www.purelandseries.com #purelandseries |