“Accordingly, I have placed my death-head formations in readiness — for the present only in the East — with orders to them to send to death mercilessly and without compassion, men, women, and children of Polish derivation and language. Only thus shall we gain the living space (Lebensraum) which we need. Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?”

-Adolf Hitler, 22 August 1939

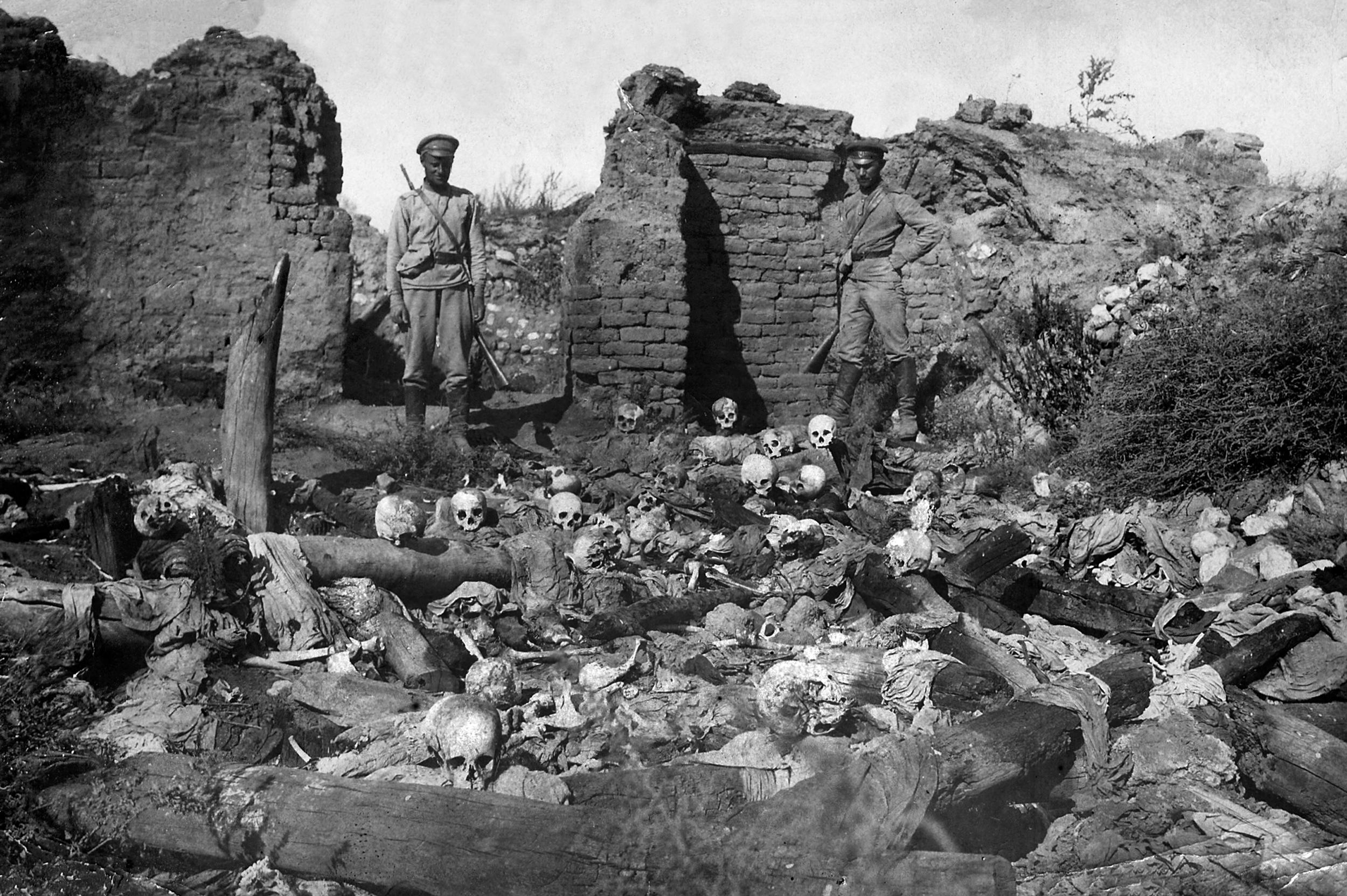

Normally, a Hitler comparison is the last crutch of a person with no argument, but this time it is unavoidable. Speaking only 24 years after the events of the Armenian Genocide in 1915, had the world really forgotten about the deaths of 1.5 million people?

It’s been 100 years since the first, modern, industrialised mass murder based on ethnic origin, and social media was abuzz this past month with articles about the Armenian Genocide. But there’s not much new to contribute to the mountain of evidence of what happened. Germany has had to answer for its crimes since the end of World War II in 1945. What’s different about what occurred in Anatolia?

Istanbul, unlike Berlin, was never captured by foreign troops, so its archives were never forced open for public scrutiny. Since it was taken by the Ottoman Empire in 1453, Istanbul remained in Turkish hands. Likewise, Ankara, the capital of modern Turkey, has never been captured either.

Since then, Turkey has suppressed even internal dialogue about the events, whether through state or non-state actors, and through both official and non-official policies. Foreign journalist have been denied entry to the country to cover the proceedings of the centennial. Prominent Armenian-Turkish journalist Hrant Dink was sentenced to a small six-month jail term but was later assassinated by right-wing activists. For a more high-profile example, Nobel Prize-winning author Orhan Pamuk was sued under Article 301 of Turkish Penal Code by an ultranationalist lawyer and ordered to pay a fine over statements regarding the genocide and thereby “insulting Turkishness.”

The manipulation of historical facts to fit ideological agendas has changed over time. As in the aforementioned quote, Hitler saw in the Young Turks an admirable ideology mobilised by ethnic nationalism that would lay the foundations for a modern Turkish state that had to be in fact, Turkicized.

To use Christian terminology, the Armenian Genocide is the original sin of the modern Turkish Republic, in the same way that the enslavement of Africans and the slaughter of Native Americans were for the United States. But the modern Republic of Turkey, just like the United States, prides itself on being a progressive, multiethnic, diverse democracy. Turkey, in the official view, is a boat of modernity and stability in a seas of states mired in chaos and ethno-religious tensions. But under the surface, there is significant tension created by historical inertia and the horrific events of the past.

So Turkey has had to shape a narrative that supports both its self image and its narrow view of history, but it is a misconception to think of Turkey’s viewpoint as denial. The official line of Turkey doesn’t deny that the killings took place. Instead, the Turkish point of view places a lot of emphasis on the historical context in which the events of the ‘Great Tragedy’ occurred – to use the translated Turkish terminology.

As World War I began to unfold and the Western Front became deadlocked in industrialised killing in the trenches of France, the entangling alliances led the great imperial powers to use their colonies and spheres of influence against one another. France brought soldiers from North and West Africa (often against their will). Great Britain brought soldiers from India and the Subcontinent. Germany, however, was cut off from its colonies. Instead, it tried to use its Orientalist tradition and its ally, the Ottoman Empire, to call on the Turkic-speaking subjects of Russia to war through religious manipulation. Likewise, Russia encouraged disaffected Christian subjects of the Ottoman Empire to rebel.

Previously, Tsarist Russia and the Ottoman Empire had been engaged in centuries of conflict in their border zones – in the Balkans, the Caucasus, around the Black Sea, Central Asia, and, of course, in Eastern Anatolia.

Things weren’t always like this. The Ottoman Empire was indeed a diverse empire with a vast diversity of languages and ethnicities. Of course, because it was a caliphate, the supremacy of Islam was implied. And religious minorities paid slightly higher taxes in exchange for protection and opting out of military service. Under the pressure of Great Britain, France, and Russia, the Ottomans began their Tanzimat reforms to encourage a more-equitable, multi-ethnic, religiously-diverse, pan-Ottoman identity, which would also turn the tide of nationalist movements amongst minorities – or majorities in the case of the Arabs.

Under the Byzantines, the Armenian church was not even allowed into Istanbul as it was viewed as heretical. But the situation was different under the Ottomans. They were elevated to high social positions and many Armenian merchant families formed a significant portion of the urban elite in eastern cities like Adana, Aleppo, Diyarbekir, Mardin, and of course in the Armenians’ traditional homeland in areas further east, like Van. In some places, Armenians comprised over 50% of the population. Armenians contributed greatly to Ottoman culture and comprised a significant percentage of the court musicians, positions of power within the centralised banking system and even the foreign ministry.

As Ottoman infrastructure began to crumble by the late 19th century, the empire was caught in a conundrum of where its future lay. Some ideological strains within Turkey, like that espoused by Ziya Gökalp, saw the Turkish people in the mirror of Europe and viewed their Perso-Arabic culture as a folk tradition that could be maintained secondary to an secular, ethnic, nationalism like what had occurred in Western Europe. At the same time people like Sultan Abdulhamid believed that the entire empire could still be held together and reformed in its own image rather than being a copy of European nationalism. In 1908, from their base in Salonica (modern-day Thessaloniki, Greece) and inspired by the ideology of Gökalp, the Party for Union and Progress staged a coup d’etat. A radical nationalist offshoot of this party, the Young Turks, would later be responsible for the genocide.

The Armenians’ success was exploited by those who needed a scapegoat for the failures of an empire, which Western powers started jokingly to refer to as the “Sick Man of Europe.” As a minority, with so many successful members of their ethnicity, they were viewed by many as part of a conspiracy, not unlike the way that Nazi propaganda portrayed pre-war Jews.

Salonica was a turning point for the genocide because it represented the breakdown of the diversity of the empire as well as the crossroads of a mass, forced exodus of Turks, Albanian, Bosnian Muslims from the Balkans. More than 900,000 were forced out of their homes by Christians backed by Russia and the Hapsburgs. Similar events happened elsewhere as the borders were gradually chipped away. It is within this context that the Turkish Republic frames its viewpoint.

For Turkey, the killings are the result of the intercommunal strife that followed the breakup of the empire.

These ‘muhajir’ communities would later settle in the Near East, in places like the Muhajreen neighbourhood of Damascus. Often, though, they were settled in cities in which Armenians prospered. They, as well as their Kurdish co-inhabitants in eastern cities, were often poor and destitute and resentful of their non-Muslim neighbours living lives of relative luxury.

As Russia began to encourage and arm Armenian nationalists as part of larger war strategy against the empire, outsiders exploited the resentment. The Three Pashas, who were commanders of a vanguard segment of the Young Turk movement, used the momentum towards their goal of creating an idealised, pure, Turkish state. Not only had the Turkish language started to be cleansed of foreign words, they also wanted their population to reflect that. They weaponised the resentment of other groups to kill and push out minorities, move in settlers and define a new state with a common identity.

Of course, not all Ottomans were in favour of the policies and it was not official state policy. After being deposed from power, the last Sultan Abdulmajid II said this of the killings:

“I refer to those awful massacres. They are the greatest stain that has ever disgraced our nation and race. They were entirely the work of Talat and Enver. I heard some days before they began that they were intended. I went to Istanbul and insisted on seeing Enver. I asked him if it was true that they intended to recommence the massacres which had been our shame and disgrace under Abdul Hamid. The only reply I could get from him was: ‘It is decided. It is the program.'”

Prior to the outbreak of World War I, Germany also recognised the importance of its Near Eastern ally for keeping the Tsar’s army tied up and thereby relieving pressure on its troops in the event of war. As such, they began to invest in the decrepit Ottoman infrastructure. In addition to building railroads, the Germans also provided weaponry, machinery, and even some spare troops to the Ottoman Army. In fact, major primary sources who documented killings were often German missionaries or Orientalists like Johannes Lepsius, or even German soldiers stationed in Syria like Armin Wegner. Nonetheless, Germany silenced the exposure of reports of the crimes so as to not upset the friendship between the two countries.

The modern German viewpoint has continued this policy. As Turks comprise the largest immigrant minority in Germany these days, the German authorities have – until recently, had an official policy of not referring to the events as a ‘genocide’. Even as of February 2015, the Linkspartei (a far-left party) attempted to question the government’s terminology in parliament about the genocide and were blocked for similar reasons, which the Bundestag thought were better-suited for academics to sort out. Likewise, their own role in the killings has been suppressed because it exists within the shadow of Germany’s own crimes in World War II.

Exploiting old rivalries, Russian President Vladimir Putin also recently managed to draw a verbal brow-beating from Turkey over referring to the ‘Great Tragedy’ as a genocide.

To put it simply, anyone who has tried to maintain good relations with Turkey has had to skirt around the issue through cleverly crafted language.

But not everyone wants to do so. In Europe, some countries that were once former majority Christian provinces of the empire like Greece and Cyprus, and also those outside its former territory like Slovakia and Switzerland, have made it a crime to deny the genocide.

To put things in perspective, Israel has neither officially recognised nor denied the Armenian Genocide. Some Israeli academics have drawn comparisons between the Holocaust and the Armenian Genocide. But when several parliamentarians attempted to raise a discussion of the Genocide, right-wing parties attacked it for possibly upsetting Israeli-Azerbaijani and Israeli-Turkish relations. A Jew of Azerbaijani origin and former parliamentarian from the Yisrael Beiteinu (Israel Our Home) party, Yosef Shaghal, later had this to say:

“I find it deeply offensive, and even blasphemous to compare the Holocaust of European Jewry during the Second World War with the mass extermination of the Armenian people during the First World War. Jews were killed because they were Jews, but Armenians provoked Turkey and should blame themselves.”

Whether or not the comparison to the Holocaust is fair is up for debate. What is not debatable, however, is that the word ‘genocide’ was coined in 1943 or 1944 by Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin to describe his first-hand experiences as a Jew under Nazi rule in Poland with the experiences of the Armenians in mind. He had followed the events of the Armenians closely as a youth and drew upon that to compare the experience of non-Germans under Nazi rule. He would later go on to use this as a basis for international law at the UN, under which more contemporary war criminals like Milosevic and Karadzic would also be tried.

In the internet age of rapid mass information, governments are increasingly finding it difficult to negotiate access to this free flow of data with transparency. Although Turkey has only recently allowed a selected number of historians access to a very curated portion of its archives, its lack of transparency is confronted by mass amounts of documentation from other sources. Turkey’s economy has been growing at a rapid pace, which is increasingly throwing it, once-again, into the spotlight as a world player. But if Turkey is ever to be taken seriously, it needs to address its past crimes – whether by state or non-state actors – in a transparent way. Otherwise, these past events, instead of the tremendous amount of its modern progress, will be the prism through which the international community will forever judge it.

For more untold stories agains the backdrop of World War I, pick up the new issue of History of War here or subscribe now and save 25% off the cover price.

Sources:

- Armenian National Institute. Armenian National Institute. 2015. Accessed April 20, 2015.

- Balakian, Peter. The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America’s Response. New York: HarperCollins, 2003.

- “The Genocide Word by Raphael Lemkin #ArmenianGenocide.” YouTube. April 24, 2014. Accessed April 20, 2015.

- Fromkin, David. A Peace to End All Peace: Creating the Modern Middle East, 1914-1922. New York, NY: H. Holt, 1989. 212-215.

- Fuchs, Richard. “Armenian Genocide – German Guilt? | Germany | DW.DE | 06.03.2015.” DW.DE. March 6, 2015. Accessed April 20, 2015.

- Lauer, Caleb. “For Turkey, Denying an Armenian Genocide Is a Question of Identity | Al Jazeera America.” Turkey Will Continue to Deny an Armenian Genocide. April 24, 2015. Accessed April 25, 2015.

- “The Term Genocide Coined Bearing Armenian Experience in Mind.” 100 Years 100 Facts about Armenia to Commemorate the Centennial of the Armenian Genocide. Accessed April 19, 2015.

- “Депутат парламента Израиля: «Считаю глубоко оскорбительными и даже богохульственными попытки сравнивать Катастрофу европейского еврейства в годы Второй мировой войны с массовым истреблением армянского народа в годы Первой мировой войны».” DAY.AZ. March 27, 2008. Accessed April 23, 2015.