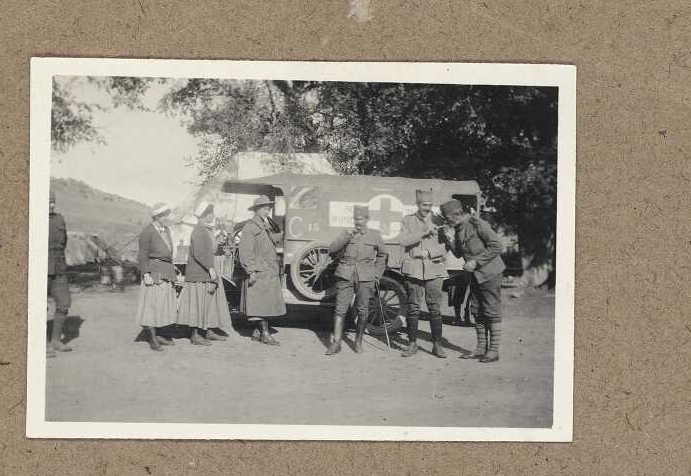

The image of the VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) nurse in World War I is dominated by the poet and pacifist Vera Brittain and her memoir Testament of Youth. But while Brittain and her contemporaries served alongside the British Expeditionary Force in France and Belgium, large numbers of women doctors, nurses, orderlies and drivers volunteered for the Serbian front instead, where far from Britain the beleaguered Balkan kingdom fought on against Austria-Hungary, Germany and Bulgaria. Their experience was very different, divided from the men in their care by language, religion and culture, they experienced the worst that this new kind of warfare had to offer.

Sally White, author of new book Ordinary Heroes: The Story of Civilian Volunteers in the First World War, explains what drove so many British women to volunteer for the Serbian campaign, and the hardships they faced once they arrived.

When did the first volunteers depart for Serbia and in what capacity did they serve?

As far as I can tell the first units arrived in Serbia in March 1915. Mabel Grouitch, wife of the Serbian Foreign Secretary Slavko Grouitch, set up the Serbian Relief Fund in London during the winter of 1914 and began holding meetings to raise funds and publicise the plight of the Serbians.

Drs James and May Berry from the Royal Free Hospital were among the first to respond, having already spent some time travelling in Serbia and knowing some Serbian. They set out in March 1915 on the same boat as the unit led by Mrs St Claire Stobart. Medical Units did not just consist of doctors and nurses. They also took an administrator, cooks, drivers, orderlies and sanitary officers.

How was the Serbian front perceived back home? Why would a volunteer be roused to do something for Serbia instead of nearby Belgium?

I understand that until Madam Grouitch began her campaign few people in Britain had any idea what was happening in Serbia. Their minds were focussed on France and Belgium and the hope/belief that the war would soon be over. As waves of refugees were displaced from their homes all over Europe people in Britain received endless appeals for help and I believe it took some time before people began to engage with the need to help the Serbians. I think what was happening there seemed very remote.

Going to the Balkans appealed to women who were more adventurous than those seeking to help in France or Belgium. Quite a few of them were mavericks who had been rejected as VADs or who lacked the necessary experience to be allowed to go to France.

Those women did not want to stay in England rolling bandages or working in War Hospital Supply Depots. They wanted to be in the thick of things, making, as they saw it, a real difference. James Berry had, as I said, prior knowledge of Serbia but taking a unit out there also appealed to him as his club foot made him ineligible for work in France or Belgium and he wanted to take an active role.

In reality, some of the male team members got frustrated to find themselves dealing with epidemics rather than wounds and some came back to Britain after just a few months, determined to work on the Western Front.

For the mostly-female volunteers, Serbia must have been an incredible culture shock: what social challenges confronted them in their work?

In spite of religious and cultural difficulties it seems that the social challenges were fewer than one might expect. The teams appear to have been treated with the utmost respect mixed with amazement that ‘English’ women and men would take the trouble to travel to the Balkans to help local people.

I think it reflects the level of need among the local population that they accepted the help on offer at face value. Although a few volunteers came across senior officers and even aristocrats, they mostly worked among people who were also used to working very hard in difficult circumstances. When members of the Stobart Unit said they were too busy setting up their tented hospital to spend a second night dining with some local officers the dinner was sent to them; fried fish, beef stew, a whole roasted lamb and salad! They never had such a good meal again while they were in Serbia.

The language barrier may have been one of the reasons for the lack of any close fraternisation or the forging of lasting friendships.

Like nurses in France and Belgium, these largely middle class women from sheltered homes seem to have coped with admirable calm with dealing with the indignity of patients with dysentery or horrific wounds. One of the greatest challenges was convincing people that letting fresh air into hospital wards would not prove fatal for the patients.

What were the physical conditions like for volunteers in Serbia?

When I started to read about the men and woman who went out to help in the Balkans I realised that their role was very different to that of volunteers on the Western Front.

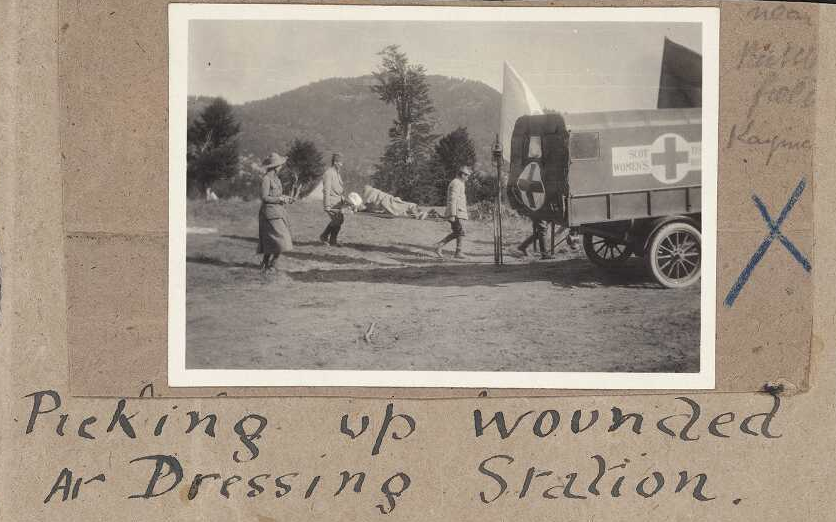

They not only went into an utterly foreign environment where only a couple of the volunteers could speak the language at all but faced a far more complicated situation. They were far from home and often felt cut off from friends and family. They were setting up hospitals from scratch, far from home. The best units tried to take out all the equipment they would need to set up and run a hospital but had to depend on tinned rations and whatever fresh food they could buy locally. Getting to their destination was always complicated and arduous involving boats, trains and wagons.

As units had up to 50 wagons of equipment loading and unloading took a long time. A number of them were involved in the Great Serbian Retreat during the winter of 1915, continuing over the mountains with the Serbian troops when even the Serbian civilians had dropped out.

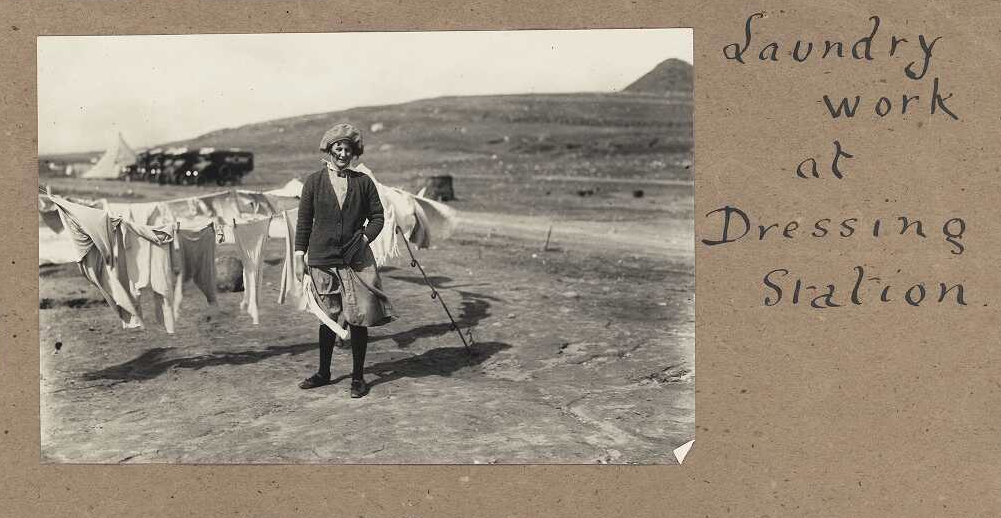

The conditions were frequently appalling as they lived and worked in either tented hospitals or previously deserted buildings that they cleaned and adapted for hospital use. They roasted in the dust of summer and froze in winter. They often lacked a decent water supply and on occasions had streams of floodwater flowing through their kitchens.

When the groups first arrived they were cushioned by all the equipment and tinned food they had taken with them but as local food shortages worsened and as they ran short of money or shipments from home life must have got even harder. A considerable number of volunteers caught typhus and a few died. I always have sympathy for the women who were in charge of ensuring there was always a good supply of clean bedding and clothing for the patients.

Notwithstanding the difficulties a number of women relished their experiences, enjoying comradeship, adventure and the chance to be useful.

Unlike British volunteers on the Western Front who had the familiar presence of the British Army to support them, who was responsible for caring for the carers, finding them places to stay, keeping them fed and watered etc?

The Red Cross gave what support it could to units it recognised and Sir Ralph Paget was appointed to co-ordinate the work of the various British Units. How far he actually managed this is unclear as he was working with groups of determined individuals who did not like to be told what to do. Dr James Berry said that while the Red Cross had stocks in their warehouses the units did well, but once their stores ran low life got harder for the units.

Every unit depended on a committed team back home who raised funds, despatched parcels and new staff and kept the team’s work in the public eye. Their work became harder and harder as the war dragged on.

Several units took sanitary officers with them to sort out supplies of clean water, extermination of lice and other pests and dealing with drains. They were often great innovators and made a vital contribution to the units’ work.

The cooks and administrators had a hard job buying food locally, when they did not speak Serbian. Monica Stanley seems to have relished the job of buying food in the local markets for her unit.

Sir Ralph Paget, the Red Cross and the Serbian Relief fund all helped decide where the units were most needed and then helped the units find suitable sites for their hospitals. As and when circumstances meant they had to move their own administrators sometimes went ahead to find a more-or-less suitable building. Mrs Stobart would not listen to advice and set up her hospital on an area that soon flooded and was a breeding ground for pests.

Units helped each other out when members fell ill, either nursing the sick or lending volunteers to each other. A few were sent to The British Fever Hospital in Belgrade but had to be returned to their units, dodging sniper fire as they went, when shelling started.

In Serbia the volunteers would have been the first Brits exposed to some of the worst that 20th century warfare could offer – bombing of civilians in Belgrade, guerrilla warfare by chetniks and reprisals against civilians as territory changed hands – do we know anything of how these new arrivals coped psychologically?

Whereas volunteers in France and Belgium often signed up for the duration of the war some of the volunteers in the Balkans had shorter contracts and were relieved to go home and get back to normality.

They gained huge support from letters from their families and friends but these could be delayed for months and it is clear that feelings of isolation and loneliness then set in. Ellie Goulding wrote to her parents that she had run out of both reading material and of conversation with her colleagues and this clearly caused her stress.

As I have mentioned, many of the people who volunteered to go to the Balkans were adventurous individualists and there was plenty of friction between some of the workers.

Kathleen Harley was so difficult that she had to leave various units when she could no longer be tolerated.

Some groups were taken prisoner by the Austrians but were treated with great courtesy. Their captivity was dull and frustrating, rather than unpleasant or frightening, and did not last too long. Workers in Russia had a harder time, constantly on the move and dealing with the effects of the Russian Revolution as well as the war.

One volunteer wrote to her parents that, having endured a retreat, she would like to experience an advance. They often had to pack up and leave at short notice and on these occasions she found leaving some of their patients behind to face certain death almost impossible to bear.

Treating civilians who had been injured by shelling was an additional strain.

I am sure that a considerable number of the volunteers suffered from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and that their problems were never recognised. Some were unable to cope in Serbia and had to go home. A fair proportion clearly relished the excitement and challenges of their work and it is easy to understand how hard they would it to fit back into the limitations of middle-class life in Britain after all they had experienced. At the end of the war a few were unable to settle back in Britain and returned to Serbia, continuing their work or running orphanages.

What inspired you to write Ordinary Heroes and beyond the Balkans, what can we expect to find in the book?

After finding a small newspaper cutting reporting Worthing’s adoption of the French town of Richebourg l’Avoué in the aftermath of the First World War. I couldn’t find anyone who had heard of any such adoptions and began to investigate.

I was soon intrigued by the role civilian volunteers played and the realisation that many had been active during, as well as after, the war. The more I read, the more engrossed I became in the various stories I came across. It seemed incredible to me that most people have only heard of the VADs who worked in France, through the diaries of people like Vera Brittain and through romantic films. The reality of what hundreds of thousands of volunteers achieved had largely been forgotten.

What I wanted to do with this book was to give an idea of the scope and scale of the voluntary work that was carried out, just how essential this was to the war effort and to recognise the bravery, imagination, enthusiasm and energy that the volunteers displayed.

The impact war has on civilians is often neglected. I drew on a considerable number of diaries and collections of letters to illustrate the various areas in which people worked. The book looks at the demands made on volunteers at home, looking after the 250,000 Belgian refugees who came to Britain during the first months of the war, setting up War Hospital Supply Depots to make hospital requisites by the million, wading through bogs to collect sphagnum moss for dressings, fund-raising, collecting eggs, vegetables, clothing and salvage, supporting prisoners of war and running hospitals.

It also looks at the groups who worked overseas in France, Belgium, the Balkans, Russia and elsewhere. Beside all these groups were the Quakers who worked to rebuild devastated communities while the war raged around them, took on the unpopular role of supporting civilian internees and continued to help refugees once the war had ended. With the Armistice came new problems and the book also looks at the charities set up to help with the rebuilding of France and helping British veterans.

Sir Douglas Haig wrote that no words could adequately assess the value of what the volunteers did and the sacrifices they made. I can only agree with him.

Ordinary Heroes: The Story of Civilian Volunteers in the First World War by Sally White is available now from Amberley. For more on the incredible hardships and heroism of World War I, subscribe to History of War for as little as £13.