The origins of modern America lie more in commerce and empire than they do in religious freedom according to Simon Targett

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

New World, Inc. is the new book from award-winning journalist Dr. Simon Targett and New York Times best-selling author John Butman that takes another look at the founding of the United States of America, tracking its origins back to the earliest traders and entrepreneurs seeking their fortune in the era of Elizabeth I. We sat down with Dr. Targett following his Oxford Literary Festival presentation in association with All About History to learn why he thinks the Pilgrim story has usurped this history as the founding myth of modern America.

Your new book is about the commercial side of the expansion into America. Why do you think this side of the story has been downplayed in history?

I think partly there’s an element of how people read history. So, they tend to focus on kings and queens, on high politics, and on religion. And I think more generally the stories of merchants through history, not just in this period, are underplayed. John Butman and I, as business writers and financial journalists, come with a mercantile perspective. And I suppose our starting point was this: we were trying to explain how America had become the country it is today? The classic founding story is the story of the Pilgrims, but this doesn’t seem to us to be the right story, the one that gets to the root of what makes America tick.

When I think of America I think of Wall Street, Silicon Valley, Bill Gates, and some of the big brands, McDonalds and all of that. It’s about entrepreneurship. It’s about making your way in the world. And as we dug deeper into the archives, we came across some different people, the merchants and their associates, whose story began not in 1620 when the Pilgrims reached America, but much earlier. We realised that their story hadn’t been properly told. Hence we called them “the Forgotten Founders”.

Having identified them, the next question was: “When do we begin this story?” For us, it begins in the 1550s. But you could make a case for beginning with John Cabot in the 1490s. He famously got permission from Henry VII to go across the Atlantic to search for what he thought would be a route to China and got, supposedly, to Newfoundland. But then nothing really happened for the next 50 years—so we decided that we couldn’t really say that Cabot’s voyage was the beginning. The reason why nothing really happened was two-fold. First, Henry VIII was mostly interested in Europe and conquest and trying to rekindle what had once been a great Anglo-French empire. He was really focused on that. And second, the merchants were mostly focused on their wool trade. Woollen cloth was their big export. Something like 80 to 90 percent of all exports were cloth, so the fortune of England was based on that—hence the Lord Chancellor sitting on the woolsack. For that first 50 years of the sixteenth century, the merchants were making decent money, so they didn’t need to think about anything else. But everything changed when the economy collapsed in the 1550s.

So, the bottom fell out of the wool business around this time?

Yes. In 1551, the demand for English cloth slumped for various reasons, including things like the value of the pound, the exchange rates and so on. There was also a glut of cloth because the English had been so industrious in producing it, and now they couldn’t sell it. Cloth exports fell precipitously in 1551 and then again in 1552. This mattered to the merchants because it wasn’t simply that they sold the cloth in return for gold and silver. They really exchanged their cloth for the things their wealthy customers wanted; luxury items like wines, silks, and spices, the great luxuries from the East, which were brought to the northern entrepôts by the Venetians and Portuguese who had the direct links with the producers in the East.

So, cut off from that business, they had to work out what they were going to do and what they decided to do was to try and go directly to the producers of the luxury items—they decided to go to China. But, of course, it was one thing to say you want to go to China, and quite another to actually go there. How on earth do you get to China—a land few Europeans had visited in the sixteenth century? Answering this question led to the founding of America and the launching of the British Empire. Sir John Seeley, the Cambridge Victorian historian, has that comment about the British empire being formed in a fit of absence of mind. I think that’s an overstatement. For sure, the merchants didn’t plan to build an empire; they planned to continue building a business. But once they had resolved that they needed to go to new markets beyond Europe, they really invested a lot of energy, brainpower and pioneering spirit into the effort. As we say in New World, Inc, the first enterprise they launched was something that eventually became known as the Muscovy Company. The idea was to try and get to China over the north Eurasian landmass—to go through what became known as the North East Passage. Why did they want to go to the northeast rather than the more conventional southern routes that had been pioneered by the Spanish and the Portuguese? Well, the Spanish controlled the route that had been discovered by Magellan around the southern tip of South America, while the Portuguese controlled the route around the Cape of Good Hope, and because they were the two dominant superpowers of the day, there was no way little England (and it was a little island at this point, relatively insignificant in the grand scheme of things) would be able to compete and go through those routes.

So they had to find other routes. Initially, they thought they could go through this northeast route to China. Of course, they didn’t get to China, but they did get to open a trade route with what was then called the Duchy of Muscovy. The Tsar of the time was a man called Ivan, who later became famous as Ivan the Terrible. With him, the merchants forged a commercial relationship with Russia and that was the first time there had been direct English-Russian trade relations for 500 years, since the days of William the Conqueror and Harold. So, even though they didn’t reach China, the merchants began once again to make money by exchanging their cloth—not for silks and spices, but for fur, for the things that the country needed for shipbuilding and so on.

For a while, that satisfied the merchants. But then there was a double whammy, when another economic crisis struck in the late 1550s. The second punch came from the fall of Calais, which took place in 1558. Calais had been an English port for 200 years. But it was recaptured by the French and, for the first time in 500 years, the English did not possess some kind of territory on the European mainland. I think of this moment as a Tudor Brexit because England really was cut off from the rest of Europe. Although their Russian trade was unaffected, they could no longer hope of getting even the reduced supply of silks and spices they had been getting from the East. As a result, after the fall of Calais, they had to renew their efforts to try and get to China.

It is at this point that a man called Sir Humphrey Gilbert enters the story. A dashing, 30-something, Oxford-educated courtier and entrepreneur, he was described by Sir Winston Churchill as “the first great English pioneer of the West”. Close to Elizabeth I, he was, importantly, a younger son. This is important in the story of the founding of America and the British Empire because in those days if you were a second or third or fourth son, you didn’t get to inherit the family estate, and therefore you had to work harder to find your place in society. One of Gilbert’s ideas was to reach China by going through what would later be called the North West Passage—through the icy Arctic waters of what is now Canada—rather than through the North East Passage. Again, as we explain in New World, Inc, he didn’t succeed, but he did trigger a renewed effort to get to China. In fact, it is worth mentioning that for the first third of our book, we don’t really talk about America. But we think it’s important to understand this backstory in order to understand how America and the British Empire came to be. Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s role was critical, and he sparked a whole series of adventures. We think that from his time onwards you can trace, albeit through a number of zig-zags, a consistent path to the first permanent English settlements in the early 1600s.

There seems to be a recurring of theme finding small successes in what might have been failures?

Yes, you’re right. These merchants ran companies that were the progenitors of our modern multinationals in terms of their structure and the idea of pooling investments. But they also paved the way for the great entrepreneurs of today. If you listen to people now like Bill Gates or Elon Musk and when he was around, Steve Jobs, they invariably say that they’ve learned more from their failures than from their successes. Where on earth does that idea, which is kind of counterintuitive, come from?

We really do think it can be traced back to this period because these early merchants were hugely influential on the evolution of America. The first Harvard Business School professor of history, a Canadian called Norman Gras, said that Sir Thomas Smythe was the first businessman to have a real impact on America. And Smythe and his associates were real believers in this idea that you need to keep persisting. For instance, as an example, there’s one story in particular that has become famous thanks to William Shakespeare, who memorialised it in The Tempest. In 1609-10, the Sea Venture, the flagship of one of the fleets going to Jamestown, was blown off course by a hurricane and struck rocks off the coast of Bermuda.

Remarkably, all the passengers survived. But for several months, the people back in England, including Sir Thomas Smythe and his fellow investors, didn’t know what had happened to that ship. As news trickled back that all of the ships had reached Jamestown apart from the flagship, the Virginia Company, fearing the worst, put out some marketing literature. They urged investors not to lose faith in the company and enterprise: “Is he fit to take any action whose courage is shaken and dissolved with one storm?”. In other words, ‘Okay we’ve had a setback, but we’ve got to keep persisting because if you’re a true investor you’ve got to accept that these things happen’. They really thought about the risks and the dangers that they were undertaking—financial risks as investors, physical risks as sailors and settlers—and I think you can see that link all the way through to the way that entrepreneurs think today.

This brings to mind two concepts that are integral to current American identity; that of the pioneer spirit and American Dream. Can these be traced back to this period?

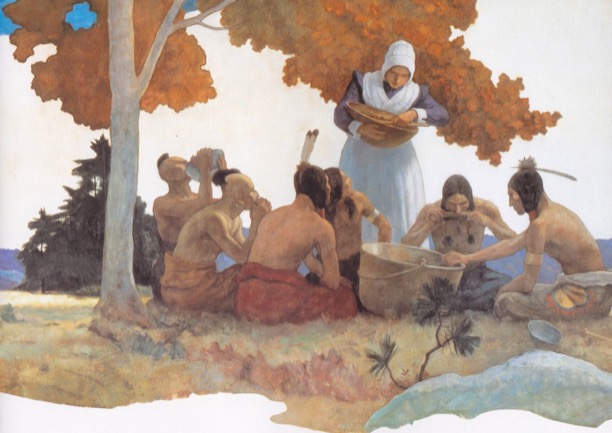

Absolutely. And this is yet another reason why we think that the Pilgrim story doesn’t really measure up as a founding story for America. The pioneer spirit and the American Dream are really two separate things. The pioneer spirit is reflected in the old idea of ‘Go West, young man’, and of course people went west, got to America’s east coast, and then over the next 200 years kept on going west until they reached the Pacific. So there was absolutely that pioneer spirit, and it manifested itself in various ways. There was a pioneer spirit in the way the sailors confronted physical danger, there was a pioneer spirit in the way the merchants created modern-style investment vehicles like companies, and there was a pioneer spirit in the way the first settlers tried to interact with the local indigenous people.

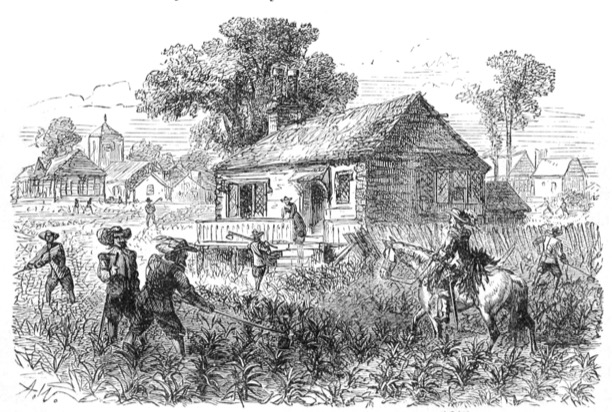

As for the American Dream, we do say that some of the earliest settlers in Jamestown were the first people to live the American Dream. Jamestown had a terribly difficult birth as a settlement and it was only thanks to people like Thomas Smythe and his merchant associates—who kept sending people and resupplying the settlement—that it actually survived. Some of the poorest settlers went as indentured servants, and they were promised their freedom and some land if they worked for five to seven years—and survived. The first group went in 1607 and in 1614, when their period of servitude ended, and some of those who were still alive decided to return to England. But some decided to stay, and they were given parcels of land and told that they could farm independently and keep the fruits of their labour for 11 out of 12 months a year. Only for one month a year did they have to produce corn and other things that would be given to the rest of the settler community.

This was really the beginning of the idea of private property and remember—these people could never, ever have dreamed of being landowners or landholders back in England. So the idea that hard work, discipline, diligence would be paid back with greater riches and greater wellbeing and security—which is really the essence of the American Dream—was formed at this early stage. Of course, there were great risks too, and many people who left England to go to America didn’t survive. But those who did, those who gambled and saw their gamble pay off, did live that American Dream.

Given all of this, why do you think it is that the Pilgrim story has become the founding myth of America?

It is a bit strange. If the Pilgrims were to come back today, they would be hugely surprised at the way their story has become the founding myth, because they were just one of many groups going across the Atlantic in search of a new life. In the classic telling of the Pilgrim story, you get the picture of a solitary and devout group of people, motivated by piety rather profit, bravely crossing the dangerous ocean, getting to Plymouth Rock, surviving that first tough winter, and then giving thanks in a ceremony that became Thanksgiving. But the real story was much different. By 1620, when the Pilgrims went to America, the Atlantic was pretty much a highway with lots of vessels going back and forth and as I say, the Pilgrims were one group among many that were originally trying to get to Jamestown and be part of what was a fast-expanding settlement. For various reasons, whether it was intended or not, they found themselves something like 500 miles further north in what is now New England and Cape Cod. There, they could practice their religion. But that was not what prompted them to leave Europe. Although their last port of call was Plymouth in England, they originally came from Leiden in the Netherlands and there, as Separatists from the Anglican Church, they enjoyed as much tolerance of their religious beliefs as they could wish for. So it is a mistake to think that they were motivated principally by the desire for even more freedom to follow their religious beliefs, What really motivated them was a desire to bring up their children in an English manner—which they found hard to do in the Netherlands—and to enjoy a better standard of living. And it is not a little ironic that they turned to a group of merchants to help them achieve their dreams.

So, in our book, we revisit—and revise—the story of the Pilgrims. And, in doing so, we pose the question: how did the Pilgrim story become America’s founding story? Well, for an answer to this question, you have to look to the American Civil War period of the 1860s. Pretty much for 150 years, the story of the Pilgrims was forgotten, lost and not much thought about. And of course the great founding fathers, like Jefferson and Washington, hailed from Virginia, from the south, and so Jamestown was more commonly the story that they talked about and remembered. But then in the 1860s a young woman, Sarah Josepha Hale—a magazine editor who is best remembered as the author of “Mary Had A Little Lamb”, the nursery rhyme—wrote to Abraham Lincoln and suggested a day of national reconciliation or a day of thanksgiving as a way of healing the divisions between the Unionists and the Confederates, between the north and the south.

Now, why on earth did she do that? Well, there’s a strange story to tell here: she was partly influenced by the rediscovery of the manuscripts of William Bradford, one of the first leaders of the Pilgrims and the man who gave them their name. He wrote an account, like a diary of events, called Of Plymouth Plantation. This document, written on velum in this spidery handwriting, was lost for decades and then turned up, strangely enough, in the library of Fulham Palace on the outskirts of London. And why was that? Well, Fulham Palace was the home of the bishops of London and for various reasons, the American colonies fell within the diocese of the bishops of London. This manuscript, which was rediscovered in the 1850s just before the outbreak of the Civil War, came to Hale’s attention and electrified her fellow Americans, who came to revere it almost like their founding document.

Abraham Lincoln was likewise excited by the whole thing and authorised a day of thanksgiving towards the end of November, which of course has been celebrated ever since. So, in a way, the reason why the Pilgrim story has been put on a plinth is because of its link with Thanksgiving and with a national celebration when the country comes together and people temporarily put aside their differences.

How much of a relationship is there between these privately funded ventures in North America and the private enterprises we would see from England in later years, such as the East India Company?

The American colonies were part of what has subsequently been called the first British Empire, which collapsed with the American War of Independence. The second British Empire was built around India after the 1760s, and other colonies such as Australia were added over time. But, early on, there was a strong connection between the two. The East India Company was launched in 1600—in other words, six years before the founding of the Virginia Company and the departure of the first voyage to Jamestown. The merchants were the common factor. For example, one of the people I’ve already talked about, Sir Thomas Smythe, was the Treasurer of the Virginia Company—in effect, the CEO and Chairman—and also CEO and Chairman as governor of the East India Company.

He had a remarkable view of the world because he was organising voyages to Jamestown, the East Indies, India, and Japan. So, the merchants who were sitting in London had this incredible global view of the world and it is therefore not surprising that it was during this period that London emerged as a truly global city for the first time. A few years before, something called the Royal Exchange had been founded by Thomas Gresham, as in Gresham’s Law [‘Bad money drives out good’], and this institution allowed merchants to come together and invest and so on. Then, 30 years later, there were two big companies, the Virginia Company and the East India Company, organising ventures and sending people around the world.

But the two companies operated in very different ways, prompted by different needs, different circumstances, different challenges. The Virginia Company’s merchants realised they had to build settlements because they wanted three things from their investment: first, wine and currants and other valuable commodities that they were struggling to get from the Mediterranean, which was broadly on the same latitude as Virginia and which had become increasingly risky with the rise of marauding pirates; second, gold and silver from the Spanish treasure fleets that were driven up the American coast by the Atlantic trade winds as they sailed across to Seville; and third, a fast route to China that they fervently believed existed through the middle of America.

They hoped that settlers could produce sought-after commodities, launch raids on the treasure fleets and discover a passage to China. By contrast, the East India Company’s merchants realised that they only needed to build trading posts because the places they reached—India, Bantam in the East Indies, and Japan—had their own populous mercantile communities. So colonies that would form the basis of the second British Empire did not develop in the East until much later.

And I think that’s another point to underline: the people we write about in New World, Inc were more focused on commerce than conquest. Empire as conquest, empire as being synonymous with slavery and exploitation—all that came later.

Just how involved was the English government in all of this activity?

English expansion and empire building at this stage was pretty much outsourced to merchants. If you look, by comparison, at what the Portuguese and the Spanish were doing, you see that their colonial enterprises were very much controlled by the monarchies—they were very much state-run. There were several reasons why merchants were at the forefront of England’s expansionary movement. For a start, the English crown was pretty poor by comparison to its neighbours. Also, when Elizabeth I reigned, she wanted to be slightly at arms length from the most ardent adventurers because she didn’t want to do anything that would potentially upset the Spanish who were the superpower of the day. Yes, she liked to tweak the nose of Philip II, the Spanish emperor, but she didn’t want to give him cause to invade— even though, of course, that is exactly what he tried to do when he sent the Armada in 1588.

But, if Elizabeth wanted what diplomats now call “plausible deniability”, she did nevertheless stay close to her leading adventurers. For instance, you can read the way she supported Sir Walter Raleigh—giving him rich rewards and perquisites—as her way of channelling state resources to a man she knew would use them to invest in ventures abroad.

And we know that she took great pride in the achievements of Raleigh, Sir Francis Drake and the merchants who funded their daring voyages. There’s a famous portrait of Elizabeth called the “Armada Portrait” and if you look closely at it, you can see that she’s sitting with the crown, pictures of the Armada victory behind her, and her right hand hovering over a globe. Her thumb is lying over where Virginia is, and her index finger is lying over the land near modern-day San Francisco which was named Nova Albion by Sir Francis Drake, who stopped there during his voyage round the world and claimed it for Elizabeth. The portrait conveys the sense that while the Spanish emperor may rule South America, Elizabeth was empress of North America. Of course, as we explain in the book, her territorial empire wasn’t all that she thought it was. But at that point, for a fleeting moment, she did think she was at last able to look the Spanish emperor in the eye.

New World, Inc. is available now from Atlantic Books. Simon Targett was a speaker at this year’s Oxford Literary Festival. For more information about the event and to stay updated on talks in the future visit OxfordLiteraryFestival.org

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!