For modern drinkers, cocktails usually evoke images of slick bartenders, polished silver shakers and elegant frosted glasses with a twist of lemon. However, they have much more historic, rudimentary beginnings. The forerunner of the cocktail – ‘mixed drinks’ – had been evolving for over a century before the sophisticated golden age of the 1920s and 1930s. Although the word ‘cocktail’ was not in common usage yet in Britain, what we now think of as cocktails were becoming available as early as the 1850s. They made a spectacular showcase at London’s first cocktail bar when Alexis Soyer, a Frenchman who made his career cooking at the Reform Club on Pall Mall, opened the Victorian equivalent of a pop-up bar in 1851.

He offered a choice of 40 drinks to the 6 million visitors who attended the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park. Because he had been asked to make non-alcoholic drinks for the exhibition, Soyer decided to set up shop by the gates, where he could make his drinks as punchy as he wanted. The scale of his ambition was reflected in the title – ‘Gastronomic Symposium of All Nations’ – and attracted around 1,000 thirsty visitors a day. Although we might view this as a wonderful early achievement that showed Londoners were keen to experiment with sophisticated new drinks, it was financially ruinous for poor Soyer.

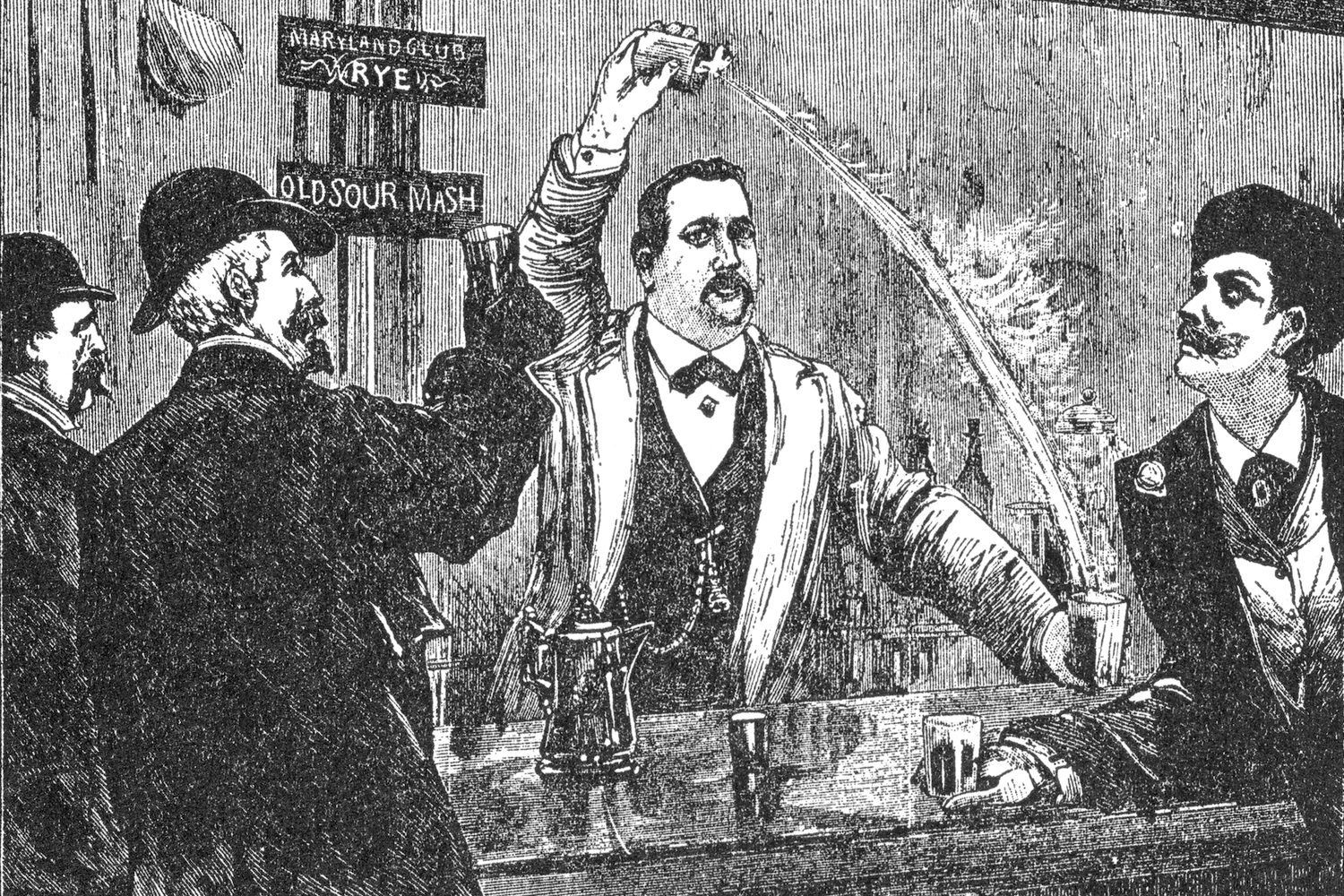

From the beginnings of ‘mixed drinks’ in Victorian Britain, American bartenders made two big contributions to the movement: showmanship and the use of ice. The latter was a novelty to the English, and when author Charles Dickens visited the US in 1842, he marvelled: “Hark! To the clinking sound of hammers breaking lumps of ice, and to the cool gurgling of the pounded bits as… they are poured from glass to glass.”

In England, drinkers were, as a rule, wary of water. It could be so unsafe to drink that just a few sips could leave you with all manner of diseases, from cholera to typhoid. Therefore, ice was both an expensive luxury and a potential health hazard. Even in 1871, the university drinking guide Oxford Night Caps had to explain to its readers that ice was safe to consume. However, it did acknowledge that when the Cobbler drink was first introduced, “ice was procured from the confectioners and fishmongers, which had been taken from stagnant ponds and noisome ditches; consequently, those who partook of it imbibed the filthy impurities which it contained.” But with the advent of steam power, ice began to be shipped from America and Canada, and so the cool beverages started to be an attractive prospect.

It was also in this period that drinks started to be served widely in glassware, rather than opaque tankards. This transition also increased cocktails’ sophistication as it became relevant how attractive they looked in the glass, and this, in turn, elevated the barman’s powers of presentation.

By the early 20th century, the notion of a glitzy bar where the barman took centre stage, serving signature drinks with theatricality, became popular. They were known as ‘American bars’ and The Spectator described, in utter bewilderment, how elevated this approach to bartending was. The publication was incredulous that men actually wanted to make careers from mixing cocktails: “The intellect that might have been used to free America from the recurring horrors of a presidential election had been so diverted as to reveal the sublimities of gin.” The publication marvelled at American bartenders’ skills, juggling the liquor so that it seemed to “spout from one glass and descend into another, in a great parabolic curve, as well defined and calculated as a planet’s orbit.”

The most legendary barman of all was Jerry Thomas, who showed off his expertise when he toured Britain in 1859. He exhibited his flair with the aid of solid silver bar utensils worth £1,000. A master self-publicist, before his guest stint at the Cremorne Pleasure Gardens in Chelsea, Thomas had leaflets dropped over London from a hot air balloon to announce his arrival. They promised, “The real genuine iced American beverages, prepared by genuine Yankee professor.”

Visitors were treated to a choice of gin, brandy or port wine Juleps, punches made with milk, whiskey, brandy, rum or gin, as well as “nectars and liqueurs of every variety.” From the ‘fancy’ section of the menu, Thomas rustled up Gin Slings, Ladies’ Blushes, Private Smiles, Sherry Snips and Brandy Smashes. Three years later, he brought out the most influential cocktail book of the time, the Bartender’s Guide, and these cocktails would go on to enter the British cocktail canon.

The Ladies’ Blush made by Thomas at the Cremorne Pleasure Gardens, became the signature drink of Leo Engel’s bar at the Criterion restaurant, one of London’s earliest permanent cocktail bars, at Piccadilly Circus. Engel doffed his cap to the Americans for their “ingenious inventions that have greatly added to the comfort of the human race.” By the end of the century, a deluge of new recipe books were available to help home entertaining match the new standard of London bars. Even housekeeping doyenne Mrs Beeton had a recipe for Martinis in her posthumous 1906 edition, listed under ‘American Drinks’.

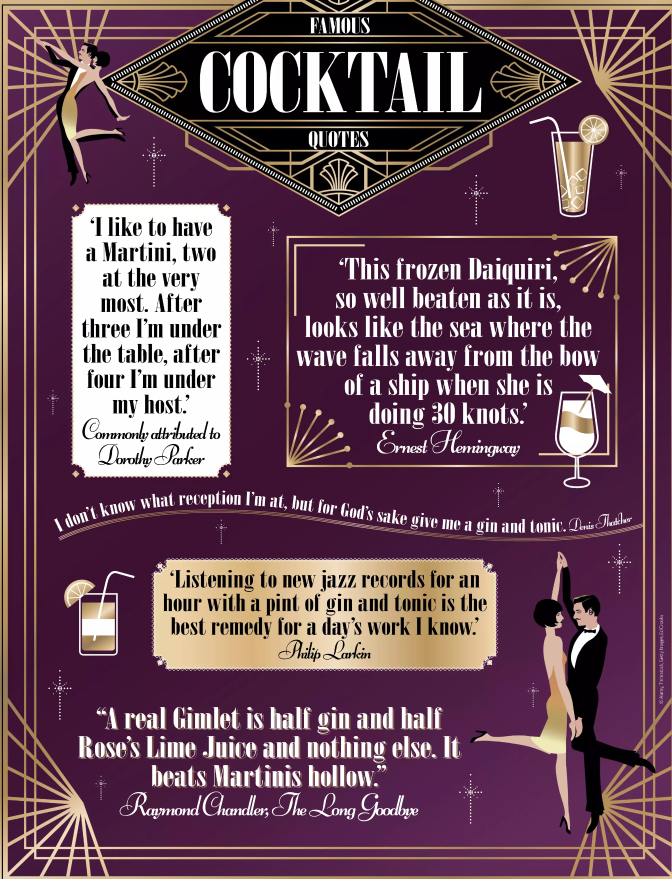

Many cocktails that were not invented by bartenders started as medicinal combinations, which then evolved into the recreational. The most famous of these include the G&T, Pink Gin and the Gimlet. G&Ts started life as a way of taking the daily quinine ration set up in malarial areas; the bitters in Pink Gin were thought to combat seasickness; while Gimlets were an enjoyable way to introduce vitamin C to a ship as an attempt to avoid scurvy, thanks to the lime juice. Exactly who first put gin and lime juice together into a Gimlet is uncertain, but there was a surgeon rear admiral Sir Thomas Desmond Gimlette (1857–1943) in the navy when it started to become popular, and he is often credited with the invention of the delicious gin cocktail.

Not all army and navy drinking could be claimed as medicinal, however. Lord Kitchener’s forces in Sudan had shipments of Pimm’s sent up the Nile in 1898, which had no possible health benefits. It could be tricky to actually get hold of the bottles once they arrived in the country, as the cocktail base was such an unfamiliar product to the locals. Major H P Shekleton in Khartoum sent a telegram to the manager of Pimm’s in July 1898 saying: “Many thanks… Pimm’s has already caused a good deal of excitement and is refused registration but hope for the best.”

This would become a repeating theme – Shekleton wrote of another hiccup in getting the Pimm’s through Europe later that year: “It has been an object of the greatest suspicion. Nobody would register it and every customhouse wanted to charge enormous duty… It has been sealed and resealed, stamped, labelled and tied up in all sorts of ways with tape and coloured string, but has survived it all and is now reposing in my cabin looking well after its many vicissitudes.”

Once Pimm’s became familiar cargo, British soldiers had an easier time getting to actually drink it. Colonel Rogers, director of army supplies in Cairo, wrote: ‘It is really very kind of Messrs Pimm to be so thoughtful about poor fellows sweltering out in these regions. It is nice to know that people at home take practical interest in our welfare.”

Into the 20th century, and cocktail drinking went truly global. Ironically, in the United States when the government decided to take the most extreme action possible – Prohibition – to stop the march of alcohol, it actually prompted some of the world’s most memorable and exciting drinks, because bartenders were forced to experiment with limited ingredients. When it became obvious by 1933 that Prohibition was failing and was accordingly abandoned, the cache of being once illicit gave cocktails an edgy glamour.

Also a lucky upshot of Prohibition for Londoners was the arrival of America’s leading barmen in search of employment. The most famous of these was Harry Craddock, who went on to compile The Savoy Cocktail Book, the highest-selling cocktail compendium in history. If Craddock had any anxieties about leaving New York, he need not have. He quickly found a job at the Savoy’s American Bar, which he ran with great flair, making it a haunt for both old-money Londoners and Hollywood stars such as Ava Gardner, Errol Flynn, and Vivien Leigh. Like Jerry Thomas before him, he knew how to self-publicise – he would even go so far as to advertise his return from holidays in The Times’ announcements.

Among his 750 drinks, Craddock thought it “a great necessity of the age” to develop effective ‘Anti-Fogmatics’ in particular. They were alcoholic drinks that were designed to clear the head in the morning, which Craddock did not think a contradiction. He insisted that drinking in the morning was beneficial, and recommended that his cocktails be drunk “before 11 am, or whenever steam and energy are needed.” One of his enduring anti-fogmatics was the unappetisingly named Corpse Reviver No 2, although one would be hard-pressed to find anyone who knocks them back for breakfast these days. With a dash of absinthe on top of gin, Cointreau and Kina Lillet, Craddock did offer the health warning: “Four of these taken in swift succession will unrevive the corpse again.” He was well aware of the potency of his own concoctions and advised, for the Bunny Hug – a mix of whisky, gin and absinthe – that: ‘This cocktail should immediately be poured down the sink before it is too late.”

He made more delicate classic drinks too, such as the ever-popular White Lady, a light combination of gin, egg white, Cointreau and lemon juice; the Bentley, to celebrate Bentley Motors’ Le Mans rally victory, made with Calvados, Dubonnet and Peychaud’s bitters; and the Mayfair, a delicious spiced mix of cloves, gin, apricot brandy, orange juice and syrup. He also championed the Dry Martini in London, for which we have been grateful ever since.

The other star of post-war London was Scottish bartender Harry MacElhone. His big break had come in 1911, at Harry’s New York Bar on the Rue Daunou in Paris, as beloved by F Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway and Coco Chanel. James Bond gave the bar more cachet still when he proclaimed it the best place in Paris to get a “solid drink” in Casino Royale. The bar claims to be the birthplace of such classics as the French 75, a gin and Champagne cocktail named after a World War I gun, the Bloody Mary, and the Monkey Gland, made with gin, orange juice, grenadine and absinthe. Embracing the bar’s louche reputation, MacElhone thoughtfully had luggage tags made for regulars that read, “Return me to Harry’s Bar, 5 Daunou.’”

Not quite so refined and elegant was the era of tiki cocktails, such as the Mai Tai and the Painkiller, which mainly had a rum base, rather than gin or vodka. The aesthetics of these tropical drinks could not be further from a sleek, clear Martini or a discreet White Lady, with their glasses full of outlandish garnishes, as immortalised by the character Del Boy on the British sitcom Only Fools And Horses. His drinks memorably captured the fashion for garish drinks like Pina Coladas, loaded with syrup, sweet fruit and showy decorations such as paper umbrellas, Day-Glo plastic stirrers and patterned straws. It originated, again, in America. After Prohibition, Trader Vic, or Victor Jules Bergeron as he was christened, opened his first restaurant in San Francisco where he pioneered rum-based cocktails. His tiki style was never as popular in Britain as it was in the United States, but it still remains a firm favourite with drinkers who have a sweet tooth.

In the early 21st century, classic cocktails made a comeback, and the emphasis at a new wave of cocktail bars was ‘mixology’, involving novel ingredients, complex flavours, and plenty of theatricality in the preparation. Alexis Soyer, Jerry Thomas and Harry Craddock would be proud – the elegance of bartending has come full circle.

This article first appeared in All About History issue 51. Never miss an issue, by subscribing from just £13.