Described by the travel writer Rebecca West as “a flabby young man with pince-nez who had a taste for clumsy experiments in absolutism”, Alexander Obrenović was brought to power by a coup and lost it in another one over his unpopular wife, Draga. The couple were just two of the many victims of Serbia’s cottage industry in regicide.

Serbia had been autonomous of the Ottoman Empire since 1815, when a hard-fought rebellion had transformed a rural hinterland into a dynamic young state and its provincial warlords into ruling princes. It had been fully independent as a kingdom since 1882.

Alexander was born into the machinations of Serbia’s first king (and last ruling prince), Milan I, and spent his early years pulled between his father and mother, Queen Natalija – both literally and in terms of their rival political alignments.

Under Austrian direction, Milan pursued a disastrous 1885 war against the emerging Bulgaria, then followed in Serbia’s footsteps by throwing off Turkish rule. As the Ottoman Empire waned and its Balkan frontier provinces began to devour it from within, Austria-Hungary and Russia eyed each other warily and sought to render South Eastern Europe their exclusive co-spheres. With Austria staking a claim on the ethnically mixed Ottoman province of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Milan was encouraged to grow Serbia’s borders at the expense of their ‘Slavic brothers’.

Natalija – the daughter of a Russian colonel and a Romanian noblewoman – was staunchly pro-Russian and pan-Slav, and to that end had successfully installed Alexander’s namesake, Tsar Alexander II of Russia, as her son’s godfather. For her, the Serbo-Bulgarian War was more than a foreign policy setback, it was an ideological anathema that had pit Slav against Slav while their bitter enemies looked on and jeered.

Sick of her husband’s incorrigible infidelity, bitter public rows and closeness to Austria-Hungary, Natalia – regarded as one of the most beautiful women in Europe – caused scandal in 1887 by abruptly upping sticks with her son to Crimea, the Black Sea resort of the Russian Empire. There, the beautiful victim of a faithless husband, she was feted by crowds as a sort of pan-Slavic Princess Diana.

The baroque divorce process demanded by the Serbian Orthodox Church rumbled endlessly on, with attempts at reconciliation stalling and Natalija outright rejecting the church’s formal ruling of divorce. She returned to Serbia “as queen” and took up her place in public life, bringing with her a moral panic about Russian meddling in the country’s fragile democracy.

Čedomilj Mijatović, the Serbian ambassador to London, setting out his stall as a member of the pro-Austrian/pro-Milan faction, wrote in 1906:

“Russia, hating King Milan, as a sort of deserter and traitor of the ‘Slavonic Cause’ utilised the general dissatisfaction of the people with the king’s divorce, and organised in Europe, and more especially in Servia, a regular campaign of the most unscrupulous calumnies.”

Amid this backdrop of embarrassment and farce, Milan I abdicated in March 1889. He renounced his citizenship and his stake in the crown, leaving his 12-year old son king, albeit under the aegis of a regency council until the boy came of age. The departed monarch had a caveat: not only would Milan leave Serbia until his son’s majority but he insisted Natalija be forcibly ejected as well. Digging in her heels and standing tall, Natalija refused to yield an inch of her royal rights, roused a crowd to fight off the police and returned to the palace in triumph. The next day, the entire Belgrade garrison was turned out to escort the queen to the border.

With that unedifying spectacle behind him, the teenage Alexander was king and – to use Milan’s own words – an “artificial orphan.”

The intrigues came thick and fast. In 1893 the 16-year old monarch dismissed his regents, suspended the constitution and assumed control of the government – soldiers stood waiting in the next room as he assured his ministers he had no need of them, a heavy handiness that didn’t go unnoticed.

Governments were formed and dissolved over the next ten years, and one one occasion he suspended the constitution for 30 minutes to clear house. Alexander did introduce a fully independent senate to try and calm the political waters, but didn’t seem to grasp that democracy wasn’t a tap to turn on and off at will. For the most part, though, the authoritarian young king had forcefully seen off the regular spats with ministers that dragged on through Milan’s reign and made government unworkable, but the army had concerns that demanded a more radical solution.

The question of a match and of an heir were of vital importance to a young nation delicately poised between empires. And Alexander chose unwisely.

“Everybody wanted me to marry. Every politician had some excellent match up his sleeve, but I believe in a question of this kind, a man should consult his own heart,” he told the sympathetic British travel writer Herbert Vivian (The Servian Tragedy, With Some Impressions of Macedonia, 1904).

While visiting his mother at the French resort of Biarritz, Alexander became so besotted with his mother’s lady-in-waiting Draga Mašin that he was reportedly waiting nervously in the corridor outside the Queen Mother’s room for a chance to bump into her. Though from a prominent Serbian landowning family who had earned renown during the war of independence, Draga’s close history was less picturesque. Her father died in a lunatic asylum, her mother was an alcoholic and, most damningly, she was a widow some 12 years older than the king. That her first husband, a Czech mining engineer called Svetozar Mašin, was an abusive drunk and gambler who had committed suicide gained her little sympathy in patriarchal and parochial 19th century Serbia. In fact it made her one particularly deadly foe: her brother-in-law Aleksandar Mašin, a retired colonel in the Serbian army, who held her wholly responsible for her brother’s downward spiral.

The French-Romanian aristocrat Elena Văcărescu pompously relayed her encounter with Draga while in Natalija’s service in her risible memoir Kings and Queens I Have Known (1904). Given she must have been blessed with incredible prescience to know that this lady’s maid would be worth studying in such detail, it’s perhaps more accurate to look at Văcărescu’s account as a retrospective reflection of a popular prejudice:

“Her countenance was well calculated to charm though not to command attention; the features though delicate, lacked refinement, and there was about the nose a deficiency of classical lines, while the mouth twitched in a nervous way as if moved to smile without the courage to do so.”

Manipulative, insincere and poorly bred, then. But this sneering indictment was in line with society gossip that branded Alexander a naive young fool and Draga the worldly cynic playing him like a tamburica. Natalija’s attempts to dissuade him from the affair were in vain, and Draga left her service and began to appear at Alexander’s side, travelling Belgrade in a carriage and living well beyond her means. Stories circulated that Alexander would do nothing without her blessing, rearranging state functions to suit her schedule – galling for a wife, unthinkable for a mistress.

Eventually, without the courtesy of informing his ministers much less soliciting their advice, Alexander announced his intention to marry. The king’s private secretary quit rather than draft an official proclamation, and Milan and Natalija, both now restored to the royal family following Alexander’s seizure of power in 1893, opposed the marriage so bitterly that they were exiled a second time. Interior Minister Đorđe Genčić confronted the monarch with a particularly low blow, telling him “Sire, you cannot marry her. She has been everybody’s mistress – mine among the rest.” With all rules of courtly behaviour clearly suspended, Alexander slapped him across the face and reminded Genčić that he himself had been cuckolded by King Milan, who made the minister’s wife one of his many sexual conquests. Genčić was imprisoned (briefly) and the entire government resigned – only the threat of abdication and further chaos convinced the church to grant the marriage their blessing.

Ominously, one of the army officers in the wedding procession of 5 August 1900 was Dragutin Dimitrijević, better known as Apis, a key figure in the coming coup and the later 1914 assassination of Franz Ferdinand. What pushed Apis and his ilk over the edge was the ‘phantom pregnancy’ of 1901 and the rumoured change to the succession that followed.

The mostly likely story is that Draga was sterile and her infertility was poorly understood, perhaps by Alexander’s wishful thinking. Instead the king interpreted some routine malady – weight gain, sickness, lethargy – as evidence of a coming heir. When the pregnancy failed to unfold as expected, slander reigned supreme and one story doing the rounds was that Draga planned to palm off her sister’s child as her own before her plot was uncovered. The Austro-Hungarian press sniped freely at the couple from across the border (journalists were reported to simply cross the Danube where they were free to telegraph gossip to Vienna and Budapest before returning an hour later to hoover up more hearsay), reporting that divorce was imminent and that Alexander had grabbed his wife by the throat and struck her in an argument over petty cash.

Outraged, the young king – his autocratic tendencies rising with his blood – decided to have Belgrade’s tongue-waggers arrested, but Draga talked him down. Either way, it was too late, their real enemies had chosen deeds not words. Draga’s two brothers were both army officers and one, the widely detested Nikodije Lunjevica, was rumoured to have killed a policeman while drunk. Furthermore the lush insisted that generals salute him despite his lower rank, demanding respect as a member of the royal family.

The latest plot doing the rounds in the officer’s mess was that Draga planned to officially enshrine the petulant and egotistical Lunjevica as her husband’s heir. This, on top of everything else, was simply too much for Belgrade’s military establishment to take. They were used to volatile rulers, royal scandals and democratic deficit, but the matter of succession put the kingdom at stake. The humiliation of the generals was salt in the wound.

A military conspiracy gathered around the figures of Dragutin ‘Apis’ Dimitrijević and Aleksandar Mašin, with former Interior Minister Đorđe Genčić as their civilian figurehead. Drunk on a poisonous cocktail of innuendo and machismo, they swore an oath to “Anticipating certain collapse of the state […] and blaming for this primarily the king and his paramour Draga Mašin, we swear that we shall murder them” and place the rival Karađorđević dynasty on the throne. (Incidentally usurping not only the alleged heir, Lunjevica, but the real one – Montenegro’s Prince Mirko who was Alexander’s brother-in-law).

The haughty Serbophile Vivien wrote in disgust:

“All through this long period, many of the traitors were enjoying the confidence and even the generosity of the sovereign they had sworn to kill, eating at his table, wearing his livery, fawning for promotion and presents.”

In short, they were perfectly placed to end the lives they blamed for Serbia’s disgrace and political vulnerability, and the plots that didn’t succeed emphasise this as much as the one that did. In early 1903 an assassin was placed in the kitchens and caught by the head chef scattering white powder in one of the bubbling saucepans. Forced to consume the meal he had tampered with, the would-be assassin died writhing in agony. A vicious end for sure, but the Austro-Hungarian press went further and claimed Alexander himself stormed into the kitchen and put a bullet through the scullion.

Against this backdrop of threats and intrigues, Alexander declared with some tragic irony:

“I am not afraid of revolutions. If anyone rebels against me, I am ready to meet him sword in hand at the head of my faithful army.”

On the night of 10 June 1903, the conspirators – somewhere between 50 and 150 army officers summoned by telegram – gathered across Belgrade, drinking and brooding. At the smokey Srbski Kruna (Serbian Crown) coffee house they toasted one another and jeered, requesting ‘Draga’s March’ played over and over again.

“The faces of the officers grew redder and more shiny, their eyes sparkled like those of wild beasts, and there was something particularly devilish about the madness of their laughter,” wrote Vivian hysterically.

Drunkenly they began to move across the cobbles toward the palaces. Despite the rakija in their veins, this was planned to the minute detail. A man on the inside of the palace opened the courtyard to the conspirators – one guard, rushing to re-bar gate was pushed aside and shot in the head – while another conspirator roused the 6th Regiment from their nearby garrison, issued them with five rounds apiece and ordered them to seal off the street around the palace. They were told the king wished Draga removed from the country like his mother before her and they were to prevent the interference of forces loyal to the queen and ignore all cries from within the palace itself.

A second man on the inside was to drug the king’s loyal aide-de-camp General Lazar Petrović to stop him getting in the way and a third would open the door to the main building. With officers covering every window and door, the remainder would rush in and do the deed. Across Belgrade, more conspirators, having mobilised and armed more regiments of unwitting accomplices from their barrack hall slumber, planned to kill the Prime Minister, the Minister of War and the queen’s reviled brothers.

Unexpectedly, the palace door proper remained firmly bolted, but armed with dynamite the conspirators blew it open – the blast blowing the fuses with the hinges and plunging the building into darkness. It wasn’t just the second inside man who had let the team down, but the third. Inadequately drugged, General Petrović rose woozily to the sound of gunfire in the courtyard. In the courtyard, Apis had been near-mortally wounded in a firefight with the palace guard, and lay bleeding, while in the street gendarmes roused from their nearby police station by the sound of the explosion exchanged shots with the army before being overrun.

Finding the phone line had been cut, Petrović stood firm on the stairs bristling with the indignation of rank and demanding explanation. Pushing past him the conspirators found the royal bedchamber empty. With a great show of resistance and reluctance the general eventually ‘revealed’ that the king and queen were cowering in the cellars.

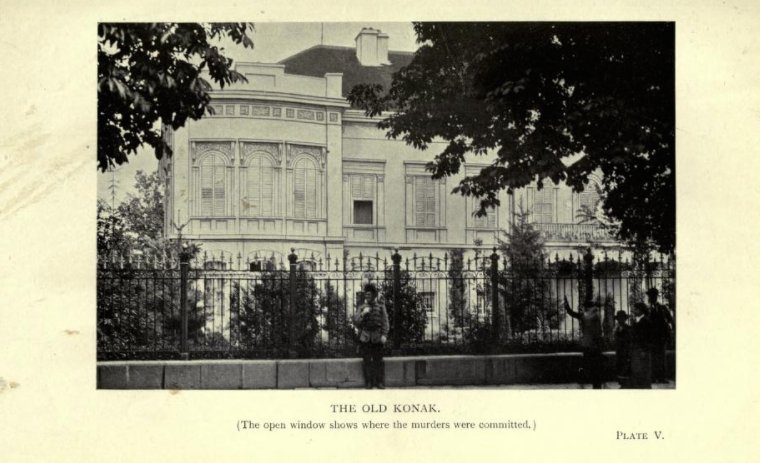

A farcical two-hour candlelit search followed with officers, growing more frantic and furious, poking behind each barrel and into each darkened corner. In the flickering candlelight they’d completely missed the concealed door of the queen’s dressing room, set flush against the wall where Alexander and Draga waited anxiously.

Realising that Petrović played them for fools, the old general was killed on the stairs and the conspirators tore around the palace, re-entering the bedchamber and slashing at curtains and cushions, and firing their pistols into furniture. A servant was discovered cowering in the royal apartments, hauled out and threatened with death, he finally nodded toward the concealed door and ended a dynasty with gesture.

There are three possible sequences of events, in one – perhaps tailored for foreign audiences or future trials – an officer entered the room alone and demanded that Alexander abdicate. Stubborn to the last, the tyrant replied “I am not King Milan” and was shot to save the nation. In another version of events the queen begged for her life, Alexander embraced her and made the sign of the cross before they were gunned down by the assembled officers, 36 bullets riddling his body and 14 riddling hers. The officers drew their swords and slashed and stabbed at their bodies, making obscene gestures and spitting obscene curses.

In perhaps the most visceral account of the bloodletting, an officer enters where Alexander is standing, shielding Draga with his body, and shoots him in the neck with an explosive bullet that would have near-severed the king’s head from his shoulders and coated the room in gore. She catches and cradles her husband when Aleksandar Mašin enters, having been promised the first pass at his sister-in-law. He shoots and misses, and more officers stream in hungrily, firing bullet after bullet at the queen before they draw their swords. They slash at Alexander’s face and hands, and slicing open Draga’s stomach as mocking reminder of her failed pregnancy.

“They seemed to emulate the exploits of Jack the Ripper on the dead body of the woman who was their queen,” noted Mijatović in disgust.

A fait accompli is only a fait accompli if people bear witness. To make good on their coup the officers drag the bodies onto the balcony to throw onto the grass below where they could be seen from the street. Ghoulishly and impossibly, Alexander is not dead – his left hand grips the railing and so the mutilation continues, his fingers severed until he finally plummets to the ground. As Serbia’s first family lay dead in the predawn gloom, the officers ransacked the palace of its valuables.

Mijatović described the chaos:

“They screamed and shouted at the top of their voices, dancing and running about the rooms like madmen, firing their revolvers at the pictures on the walls, at looking-glasses and candelabras; some of them broke with axes the bedstead of the royal couple and smashed all the fine things on the queen’s toilette table; called for wine from the king’s cellars and the trembling servants obeyed their orders. Others who felt the air of the palace hot and sulphurous, rushed into the courtyard, ordered tables to set out on the carriage drive.”

After two hours, the Russian ambassador, who had watched the whole affair from his residence across the road (“through his fingers,” shrieks Vivian) emerges and orders his servants take the bodies inside. An officer standing guard unceremoniously blasts the gore from the king and queen with a garden hose before they are placed on a kitchen table. Surgeons are summoned to perform a politically expedient autopsy, ruling that Alexander was mentally unstable and Draga was infertile, as if either were suitable grounds for this stomach-churning slaughter.

After a brief lying in state – the king dressed in black and the queen in a pale pink dress – while a steady stream of visitors field past, according to Vivian, spitting on the queen and making lewd remarks, they were buried with little fanfare while the conspirators were honoured as “saviours of the nation.” Flags and bunting went up in the streets, and cannons fired triumphantly.

Peter Karađorđević returned from his exile. A smart, considered man with the vision to build a modern state he had been educated in Switzerland and served in the French army. He was a moderniser and a reformer, but when it came to treating Serbia’s open wounds, he found himself poorly placed to condemn the crime of which he himself had been the net beneficiary. Instead a tight knot of scar tissue grew over the affair, pulsing with sickness.

“The king is a nullity,” reported an official at the Austrian Foreign Ministry in November 1903. “The whole show is run by the people of 11 June.”

With the military clique at the heart of the coup having proven exactly what they were capable of, the new king, Peter I, and government kept them very much on side, in fact three of the government’s newly minted ministers (one of them replacing the murdered Minister of War) were members of the conspiracy.

Dragutin ‘Apis’ Dimitrijević, on his recovery, was formally thanked by the Serbian parliament and feted as a hero. In winter 1905 the king chose him as a travelling companion for his son Crown Prince George as he made his way across Europe on a hearts and minds tour. He was later appointed Professor of Tactics at the Military Academy. Only very grudgingly in 1906 as a result of almost total international isolation (only representatives from Greece and Bulgaria attended Peter I’s coronation), were the conspirators moved away from the centre of power in Belgrade. Not punished – many were promoted – but removed from the eyeline of Europe.

Perversely, while Peter’s reign witnessed the birth of a more robust democracy than that of the Obrenović kings – fondly remembered as a “Golden Age” of domestic prosperity and liberalism – foreign affairs became a hostage to the belligerent militarists who had been empowered by the coup. The delicate balancing act between Austria-Hungary and Russia was thrown off kilter by the murders and never recovered. The next decade would see a series of diplomatic spats and feuds that by 1914 would make war seem not only inevitable, but a welcome solution to Serbian insolence and Austro-Hungarian arrogance.

In 1911 Apis helped to found Ujedinjenje ili Smrt (Unification or Death), a tightly structured terrorist network dedicated to building a Greater Serbia by whatever means necessary. Better known as the Black Hand, its methods were made clear by its symbol of a skull and crossbones, knife, bomb and vial of poison. Royal patronage appeared here too, and the Black Hand’s journal, Pijemont, was founded with a donation from Crown Prince Alexander (George having renounced his place in the succession after kicking a valet to death). Prince Mirko of Montenegro, smarting from being shoulder barged from the succession by the May Coup, was also a member, hoping that the Black Hand would usher him onto the Serbian throne.

Militant nationalists like Apis believed that Croats, Bosnians and Macedonian Slavs were Serbian and by right their lands belonged with – or to – Serbia. This arrived in tandem with the rise of Yugoslavism in the Balkan provinces of Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, the growing sense that South Slavs (Yugoslavs) were better bound together in their own nation inspired by the model of the free and democratic Serbia. Unlike the Greater Serbia ideal of the Black Hand, this cut across religious and ethnic lines but from the outside the methods and aims were the same – resistance to Austria-Hungary and Turkey, and solidarity with the Kingdom of Serbia. These fires were further fanned by the First Balkan War (1912-1913) that saw a triumphant Serbia split the Ottoman province of Macedonia with Bulgaria. The opportunistic Second Balkan War (1913) saw Serbia turn on its neighbour and ally, snatching a further chunk of Macedonia from Bulgaria.

In 1913 Apis became head of Serbia’s Military Intelligence, which plugged the Black Hand into the very heart of the Serbian military establishment.

Similarly, while Apis’ star rose with the First Balkan War, many of the officers complicit in the May Coup returned to the active list, directing the war effort from the front and not just the shadows. With the territorial ambitions of Greater Serbia realised in the south, they turned north and west. Slavic nationalists in Austro-Hungary were courted by the newly invigorated network, in particular Mlada Bosna (Young Bosnia), the desperate student activists that the Black Hand would issue with Serbian Army sidearms and cyanide capsules, and point in the direction of Franz Ferdinand’s state visit to Sarajevo.

So prominent and so feared were the Black Hand – and Apis in particular – that Crown Prince Alexander (named regent in 1914 as his elderly father’s health faltered) began to gather his own military clique around him, nicknamed the White Hand and made up predominantly of enemies and rivals of Apis. Meanwhile the long-serving Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić cultivated a fierce inscrutability, remaining utterly ambiguous in terms of his sympathies and loyalties that allowed him to bob and weave through the debris of Black Hand plots and counterplots. Eventually, at the close of World War I – a particularly bloody and bruising experience for Serbia – Pašić had Apis and the Black Hand leadership executed following a show trial. Justice of sorts, but 15 years too late as by 1918 all of Dragutin Dimitrijević’s aims had been realised: Austria-Hungary was no more and Greater Serbia had been born in the form of the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (from 1928, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia).

“Now I realise that when Alexander and Draga fell from that balcony the whole of the modern world fell with them,” Rebecca West observed in 1937. “It took some time to reach the ground and break its neck, but its fall started then.”

James Hoare is Group Editor-in-Chief of All About History and History of War. For more on the prelude to World War I, subscribe to History of War for as little as £10.50.

Sources:

- C Clark, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, Penguin, 2012

- JP Newman, Civil and Military Relations in Serbia 1903-1914, Cambridge University Press, 2015

- R West, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey Through Yugoslavia, Penguin, 2007

- V Herbert, The Servian Tragedy, with Some Impressions of Macedonia, Grant Richards, 1904

- H Vacaresco, Kings and Queens I Have Known, Harper & Brothers, 1904

- C Mijatović, A Royal Tragedy, Being the Story of the Assassination of King Alexander and Queen Draga of Servia, Eveleigh Nash, 1906