On the eve of the 400th anniversary of his death, a 1623 copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio has been discovered at Mount Stuart House on the Isle of Bute, off the west coast of Scotland. We spoke to Professor Emma Smith from the University of Oxford, who verified the book’s authenticity, about how this find will help us to understand more about Shakespeare and his evolution from playwright to literary icon.

Can you tell us a bit about the First Folio, and why it’s so special?

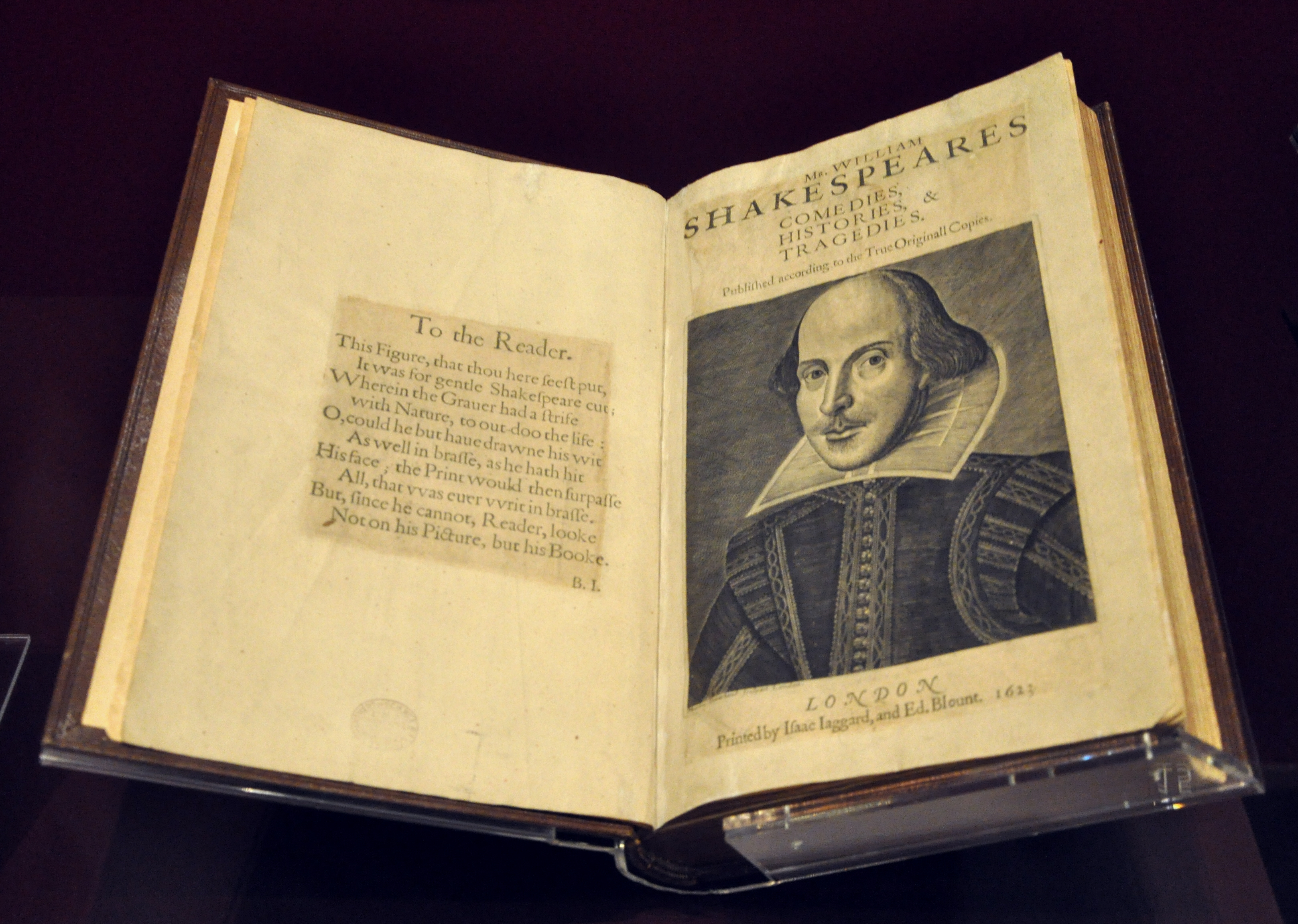

The First Folio is the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays. It was published in 1623, after his death, and for 18 of his plays it’s our only source – so to put that another way, we would have lost half of Shakespeare’s works had it not been printed.

It gives us the first and the only verified image of Shakespeare and it’s a really important book in that it made Shakespeare last not just in literary and cultural terms but in practical terms – it was a safe way to keep his work in a big, heavy book that doesn’t get lost easily, so that’s a really important element in securing Shakespeare’s reputation in the first century after his death.

Did it sell well at the time of publication?

That’s a good question as we don’t really know. We reckon there were around 750 copies printed, which is a middling size print run for the time, and we know that there is a reprint nine years later in 1632 – some people will say ‘It was reprinted in only nine years’ and other people say ‘God, it took them nine years to shift these copies’ – it depends how you look at it.

My own view is that seven years after someone dies is quite a low point in their critical reputation. They’re not fashionable and current and they’re not yet vintage or nostalgic or classics, so I think perhaps Shakespeare was not an obvious thing to try to sell in 1623 and what this book tries to do is reorient a writer known for theatrical works into something more canonical and literary.

How many copies exist today?

About 230, but it’s a measure of how iconic a book it is that people are interested in it even though – or perhaps because – it’s not that rare.

The discovery of a First Folio at Mount Stuart house is very timely, considering this month marks the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. When did you first hear about this possible new find?

I got a call last September and I went to Bute off the west coast of Scotland to have a look at it. I was very sceptical – I thought it was very unlikely that they would have a First Folio because this is such a studied book and we know a lot about it. I thought they might have a later edition or perhaps a facsimile but it turned out that it was genuine.

How did you go about verifying its authenticity?

The verification is based on two things. The first and probably the most important is watermarks, so we know the paper stock that was used by William and Isaac Jaggard when they printed the First Folio, so we can check those watermarks – they’re very difficult to fake. We also know in absolute minute detail how every word is printed, where there are errors, where there are turned letters or glitches, and we can match those with this new one.

What can we learn from this copy in particular?

We can learn some interesting things about the reception of Shakespeare. Either we love these books because they’re pristine and perfect and they seem like a little time capsule, or we love them because they’ve had a continuous history of people using them, and this Bute copy is in that second category; it’s not perfect – it’s been used, it’s been re-engineered to make it a more manageable book; it’s been split into three so it’s much lighter to carry, it’s easier to sit in a chair and look at it.

The First Folio is a study book really; it’s a book you have to have on your desk, and that tells us something about how Shakespeare was becoming domesticated, it became something to do with leisure rather than with study. It’s connected with the 18th century editor Isaac Read who owned it, and he got it from a significant Shakespearean actor in Covent Garden called John Henderson. So we know bits and pieces about its history and we know it’s circling around a sort of overlap between Shakespeare in the theatre and Shakespeare on the page, so that’s interesting.

And there are some earlier marks that we haven’t been able to trace yet – doodling etc – which shows this was not a valuable book to them, this was an ordinary thing, and it’s good to be reminded of that when we’re so in awe of it as an object now.

Do you think there is a chance that more copies of the First Folio are out there that are yet to be discovered?

I wouldn’t be surprised, actually. These are big books and you don’t lose them by accident. There may be places where they’ve fallen out of current knowledge but they’re probably going to be in rather neglected libraries, a bit like Mount Stuart. I don’t think they’re going to be in someone’s attic, although it would be nice if they were.

Read more about the First Folio and Shakespeare’s secret life in the new issue of All About History or subscribe now and save 25% off the cover price.