The Legend:

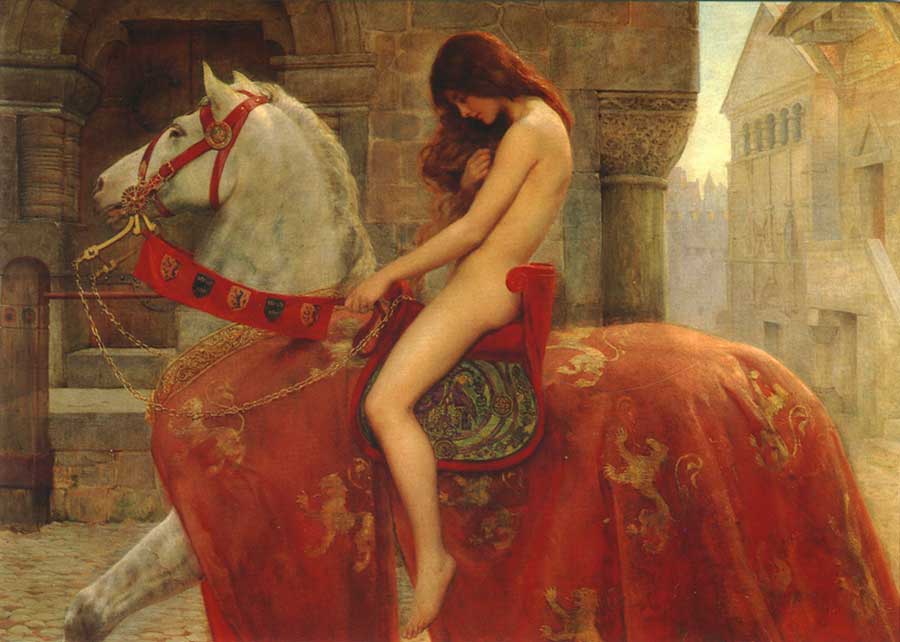

There are various different versions of Godiva’s naked ride written by different authors though the years, but the most common version that has entered into legend is as follows:

The people of Coventry had been inflicted with a heavy tax by the earl, Leofric. Lady Godiva, upon witnessing the plight of her people, went to her husband and begged him to relieve them of the tax. He scolded her for questioning his authority, and warned her not to ask him again. However, she refused to back down and finally her exasperated husband said, “Mount your horse naked, then ride across the town’s marketplace from one end to the other, with all the people assembled, and when you return you shall have what you ask for.”

To Leofric’s surprise, upon receiving his word the countess mounted her horse naked, as agreed. She then released her hair from her head and let it fall and cover her whole body. She commanded all the people to stay indoors, away from their windows, upon pain of death. However, as she rode across the marketplace there was one who couldn’t resist looking, but it cost him his life. Godiva returned to her astonished husband who had no option but to fulfil his promise and release the people from the harsh tax.

Although some details differ, the main story remains the same in all accounts – the noblewoman sacrifices her own modesty to relieve her citizens of a cruel tax imposed by her husband. This story of the sacrificial ride has entered into legend, and in memory of this event a statue of the man who couldn’t resist looking out of his window has stood in Coventry since the 16th century.

Who was she?

Unlike Robin Hood, King Arthur and many more famous legends, what we do know is that Lady Godiva was certainly a real person who lived and breathed. Godiva – or Godgifu, in Old English, was one of the most prominent women in Anglo-Saxon England. She was a wealthy woman of high status in her own right, and was also married to one of the three most powerful earls in the kingdom – Leofric.

Godiva lived in a time of great political turmoil, her lifetime likely spanned nine different kings of England. Although we do not know her parentage, we know she was a noble lady with large estates to her name. Godiva married Leofric before 1040 and their combined estates enabled them to control an enormous amount of wealth. Godiva held many of these estates herself, Coventry included, as Anglo-Saxon law allowed women to do this.

There are numerous instances that prove Godiva’s generosity; she made donations to the monastery at Stow near Lincoln and also to many religious houses across the country. At Coventry in particular Godiva and her husband donated so many jewels, gold and holy relics that “the very walls seemed too narrow for all this treasure.” There is also evidence that she donated some of her land to monasteries.

After the death of her husband in 1057, Godiva lived on until sometime between the Norman conquest in 1066 and 1086. Her name can be found in the Domesday Book in 1086 and she was the only woman to still own land after the conquest. Her son was a man of little political importance, but her granddaughter went on to marry Harold Godwinson and became the last queen of Anglo-Saxon England.

Considering what a prominent and important figure of status Godiva was, it is surprising that there is no contemporary reference at all to her famous naked ride, which she is known for today. If we consider that Anglo-Saxon chroniclers were avidly recording every morsel of news that came their way, it is highly suspicious that not a single one wrote about the naked ride of one of the most important women in England.

So where does the story come from?

The famous story first emerged 200 years after Godiva’s supposed death in the St Albans Chronicles known as the Flores Historiarum, seemingly out of nowhere. Compiled by Roger of Wendover and Matthew Paris, this 13th-century account’s considerable age does warrant some further investigation, however, numerous historians dispute its reliability. Matthew Paris especially, was known to add much imaginative embellishments to his accounts, and was willing to sacrifice factual accuracy for a riveting story. Considering the only accounts of Godiva prior referenced her as a saintly wife who made great donations, it is easy to see where he may have been inspired to pen a tale of self-sacrifice and selflessness.

It is very peculiar, however, for the story to suddenly emerge out of nowhere in such detail. It is likely that Paris and Wendover added embellishments to the story, but creating it from scratch seems a dubious claim to make. In a chronicle written by Richard Grafton in the 1560s, there is reference to a ‘lost chronicle’ written by Geoffrey, the prior of the monastery of Coventry between 1216 and 1235. Grafton claims that the Godiva story first appeared in this lost chronicle. We cannot be sure how accurate Grafton’s claims are, but he was able to provide additional details that added to the Godiva legend, helping it to grow and grow.

Links to folklore

Whether we can trust Grafton or not, the story certainly didn’t appear from thin air. There are numerous similar figures to Godiva throughout Celtic and Nordic mythology. There was particular interest in these ancient legends around the time Wendover and Paris penned their account, and it seems likely they were influenced by them. Monks were known to travel far, while also accepting visitors from far and wide, so it’s no stretch to believe that they heard traditional stories from all over Western Europe.

The Celtic goddess Epona and the Welsh goddess Rhiannon were both women heavily associated with horses. Rhiannon in particular was known for her affinity to horses, but also her wealth, generosity and beauty. The Norse heroine Aslaug was another well-known figure who was famed for her beauty but also her cunning – such as one instance where, upon being asked to arrive neither dressed nor undressed, she arrived wearing a net. There were also a number of fertility cults that had ceremonies involving a naked woman riding a horse to benefit her community. Although these links may seem tenuous, Paris and Grafton were writing at a time when verbal folklore and legends were finding their way into the written form.

As time went on the story grew and grew – Godiva was originally accompanied by soldiers, then her handmaidens, then she was completely alone. The order for nobody to watch her also emerged later, as did the figure of ‘Peeping Tom’ who is blinded in one account and struck dead in another. The Victorians in particular were fascinated with the story – prompting an array of ballads, poems, plays and sculptures based on the legend.

Is it true?

It is possible that the Godiva ride did happen, entered into oral tradition and was finally written down 200 years later. As for the lack of its presence in the historical accounts, this could be attributed to the fact that the people were ordered not to look, and the chroniclers also chose to pay such respects. However, when the story is scrutinized alongside what we do know of that era, its credibility begins to be chipped away.

First of all, the figure of Leofric – in the story he occupies the role of a cruel, unrelenting ruler, willing to humiliate his wife to prove a point. However, this directly goes against what we know of the earl.

Leofric was shrewd in his political judgments and his marriage seems to have been a successful and honourable union. There are no accounts at all that question his dignity as a ruler, or indicate in any way that he was cruel or overbearing. The reason Leofric was successful is because he was very politically conscious in a time of great instability. As an eminent figure it is almost unthinkable that he would subject his wife to such a humiliating ordeal that would have demeaned not only her, but himself and his authority. There just isn’t any evidence at all that backs up the image presented of Leofric in the legend.

Perhaps even more revealing is the fact that Coventry was Godiva’s, not Leofric’s, estate. If the citizens were suffering under a tax, she had no need to plead for Leofric’s mercy, she could levy a tax on the town by herself. If the tax instead was the ‘helegeld’, imposed by the king, again it would be useless pleading with her husband, and she would have had to take her case to the monarch himself.

Further doubt is created if we look at the location of the naked ride – Coventry. In the 11th century, it was no town, but instead a small village with no more than 300 people. This was certainly not big enough to have a marketplace, and the largest building would have been the monastery – a very unlikely setting for the naked ride.

If we consider all these facts, along with the conflicting contemporary accounts, it seems highly likely that the story of Godiva that has entered legend today is one born not out of facts, but of folklore and oral tradition developed over many hundreds of years.

To help dissect the truth of more ‘historical’ tales, pick up the new issue of All About History or subscribe now and save 25% off the cover price.

References:

- Great Tales From British History, Robert Gambles

- Lady Godiva: A Literary History Of The Legend, Daniel Donoghue