Main image: Owain Glyndŵr painting at Wales’ first Parliament – Owain Glyndwr Centre by Morien Wyn Jones

Owain Glyndŵr is the national hero of Wales. In the early 15th century, he led the last serious rebellion against English rule for Welsh independence, fighting a largely guerrilla war that depended on attacking castles and deliberately avoiding the English in open battle. Nonetheless, Glyndŵr fought and won several pitched battles that secured his place in Welsh history. His proud defiance caused severe economic and political problems for King Henry IV that blighted most of his reign. Eventually, the revolt would be suppressed, but like William Wallace in Scotland, the memory of Glyndŵr’s spirit of Celtic independence made him a national icon, which continues to the present day.

War of cultures

Wales had been under English control since 1283, when Edward I systematically conquered the country and displaced the native princes. To secure his conquest, Edward declared his own son and heir to be the Prince of Wales and built formidable castles, particularly in the north of the country. These fortresses were a powerful symbol of English dominance in a conquered Wales, and in the following century, Englishmen and their families were encouraged to settle there to cement English dominance, much like the Ulster plantations in the 17th century. Powerful ‘Marcher’ lords, the descendents of Anglo-Norman aristocrats, supported the settlements. They held lands on the Welsh border and asserted an authority that was semi-independent to the English crown. One of these Marcher lords, Baron Grey of Ruthin, would inadvertently spark the revolt that threatened to destabilise not just Wales but England too.

By 1400, many Welsh people had become deeply resentful of the English occupation. The new settlements meant that the Welsh were economically and racially discriminated against and were denied key appointments in the church and government. They were also more highly taxed than their English counterparts, yet the revolt was started by one of the few Welshmen who had actually benefited from English rule.

Owain Glyndŵr was middle-aged in 1400, having possibly been born in 1359, and was a prominent member of the Welsh nobility. His direct ancestry included the Princes of Powys and Deheubarth, both of whom had lineages to the House of Gwynedd. This dynasty had produced the original princes of Wales, and claimed to be descended from legendary British kings. Glyndŵr’s great-grandfather was one of the few princely survivors of the 1282-83 Conquest, and as such he was the most prominent native Welsh nobleman.

As befitting his noble rank, Glyndŵr had studied law in London, and at this time was loyal to the English crown, performing military service in Scotland in 1384 and at Sluys in 1387. However, in 1400 he entered into a bitter land dispute with his neighbour, Baron Grey of Ruthin. When the case was delivered to parliament, Glyndŵr faced discrimination because he was of Welsh nationality, and then Grey tried to accuse Glyndŵr of treason. What happened next is uncertain, but on 16 September 1400, there was an assembly of Welshmen at Glyndyfrdwy, which included many of Glyndŵr’s relatives as well as Welsh churchmen. They issued a declaration that “elevated Owain” as Prince of Wales and called for the death of Henry IV and the obliteration of the English language.

This was not a random coincidence – Henry IV had only recently usurped the throne from Richard II and declared his eldest son Henry to be prince of Wales. As usurpation was considered a grave sin, the Welsh refused to recognise the young Henry as their prince. On 16 September 1400, Glyndŵr used this transformed situation to descend “in warlike fashion” to burn his enemy Grey’s estates at Ruthin with 270 men. Afterwards, the ‘English’ towns of Denbigh, Rhuddlan, Flint, Hawarden, Holt, Oswestry and Welshpool were attacked. The rebellion had begun.

Mab Darogan rises

Sources for the revolt are scanty, and much of what happened is disputed. Nevertheless, it became an economic, military and political nightmare for Henry IV. In the aftermath of Glyndŵr’s initial attacks, Henry ordered levies in the Midland and Border counties. An English commander called Hugh Burnell defeated the rebels and Glyndŵr “escaped into the woods”. The king then toured northern Wales with his troops, mistakenly thinking the attacks were a minor disturbance. In early 1401, English chroniclers felt confident enough to report: “The country of North Wales was well obedient.” However, the revolt quickly resurfaced when Conwy Castle was dramatically captured by the Tudur brothers from Anglesey and held for eight weeks. This was soon followed by Glyndŵr’s first victory, in a battle at Mynydd Hyddgen in June 1401.

This clash took place in a valley in the Cambrian Mountains and began when a large force of 1,500 English and Flemish soldiers from Pembrokeshire attacked Glyndŵr’s army, which was encamped at the bottom of the Hyddgen Valley. Henry IV had given orders to quash the growing rebellion while Glyndŵr had been marching southwards with a small force of 120 mounted troops – aiming to pursue a guerrilla war in English-controlled southern Wales. The only account of this battle was written in the 16th century, in Annals of Owain Glyndŵr, and it states:

“No sooner did the English troops turn their backs in flight than 200 of them were slain. Owain won great fame, and a great number of youths and fighting men from every part of Wales rose and joined him, until he had a great host at his back.”

Though it’s uncertain how the Welsh defeated the much larger English force, it was likely a case of speed over strength. The Welsh were lightly armed and mobile and were equipped with longbows (which were Welsh in origin), so it is probable that they simply outmanoeuvred the more heavily armoured English. What is certain is that Glyndŵr had now become the leader of a national movement.

The victory at Mynydd Hyddgen was followed by a symbolic moment at the Battle of Tuthill on 2 November 1401. Tuthill was a high position overlooking Caernarfon Castle, the headquarters of English domination in northern Wales. The encounter is most famous as the first occasion when Glyndŵr unfurled a flag bearing a golden dragon on a white field. This recalled the symbolism of the legendary Uther Pendragon, and Glyndŵr deliberately drew comparisons between his revolt and Welsh political mythology. By invoking Arthurian legend, Glyndŵr was presented as ‘Mab Darogan’ (the ‘Chosen Son’) who would free the Britons of Wales from the subjugation of the Anglo-Saxons. There are few details of the battle itself, but it is believed that the fight ended inconclusively with an estimated 300 Welshmen dead. However, the Battle of Tuthill demonstrated the isolation of Caernarfon and Glyndŵr’s ability to attack English positions in Wales with impunity.

After Tuthill, Glyndŵr began to seek external alliances and addressed letters in French to the king of Scotland and also correspondences in Latin to the Gaelic lords in Ireland. His rising prominence gained further currency when he won the greatest clash of the revolt at Bryn Glas.

This battle was fought on 22 June 1402 near the towns of Knighton and Prestaigne in Powys. The English, under the command of Sir Edmund Mortimer, numbered some 2-4,000 men, while the Welsh had approximately 1,500 men. Mortimer’s force also had a considerable number of Welshmen from Maelienydd, and these troops would play an important part in the outcome of the battle.

Mortimer’s men advanced on Glyndŵr’s force, which was occupying a hilltop position. The smaller Welsh army was divided into two sections: one on the crest of the hill to encourage Mortimer’s men to attack, and the other decamped in a hidden valley alongside the hill. As Mortimer’s army advanced up the slope, Glyndŵr’s longbowmen fired downhill with deadly effect, and although Mortimer’s army also had longbows, they were less effective when fired uphill. When the two armies engaged in battle on the hill, Glyndŵr’s men concealed in the valley attacked Mortimer on the right flank and rear. During the bloody battle that followed, some of the Welsh bowmen in Mortimer’s army defected to Glyndŵr and fired on their former comrades. This turned the tide and saw the English routed, Mortimer captured and between 200-1,100 Englishmen killed.

Chroniclers described how, “The corpses were left lying under their horses’ hooves, weltering in their own blood, as burial was forbidden for a long time afterwards.” Welsh women reputedly mutilated the English corpses in what would prove to be the most significant moment of the revolt.

Mortimer’s family were prominent Marcher lords who had a greater claim to the English throne than Henry IV, so the English government procrastinated over Mortimer’s ransom. This led Mortimer to defect to Glyndŵr, and he even married Glyndŵr’s daughter Catrin on 30 November 1402. This provided the Welsh revolt a much greater legitimacy and helped to destabilise English politics for several years after the matter.

Henry IV hits back

Bryn Glas shocked Henry IV, who decided to personally lead a new campaign into Wales. For the king, the revolt was becoming personal as his own estates were under threat. It has been calculated that the king and Prince Henry exercised lordship over half the surface area of Wales and could normally expect their Welsh estates to provide an annual income of £8,500 (almost £4 million in today’s currency) and often much more. As the revolt spread, not only were these revenues lost, but additional funds had to be found to deal with the rebels. Henry IV’s 1402 campaign after Bryn Glas planned to encircle the Welsh from the English headquarters at Shrewsbury, but it was thwarted by bad weather. The king himself almost died when his tent blew down in a storm and he was only saved from being crushed by his armour. Henry IV would personally lead six campaigns into Wales between 1400-05, but they were all to little effect and he would eventually leave the frustrations of endless campaigning to his son and the nobles.

Bryn Glas resulted in tighter English sanctions against the Welsh. When parliament assembled on 30 September 1402, it issued statutes prohibiting public assemblies, the bearing and importation of arms and the keeping of castles or holding office by Welshmen. Special mention was made to those allied or friendly to: “Owen ap Glendourdy, traitor to our sovereign lord and king.” In fact, Glyndŵr was not taken off a list of traitors until 1948.

In an attempt to regain the initiative, Prince Henry was appointed as royal lieutenant in Wales on 8 March 1403, but this did little to change the military situation. Throughout 1403 Glyndŵr continued to raid and attack castles across Wales, including at Newcastle Emlyn, Llandovery and Kidwelly. At the same time his success was fermenting a civil war in England. The powerful Percy family, who had helped Henry IV during his usurpation, did not feel properly rewarded. He colluded with Mortimer and Glyndŵr to raise an army to overthrow the king and replace him with Mortimer’s nephew, the Earl of March, and to recognise Welsh independence. Henry IV fought and won a vicious battle at Shrewsbury on 21 July 1403 to prevent the Percys from linking up with Glyndŵr, but still the revolt in Wales continued unabated.

After the Battle of Shrewsbury, the Welsh started to receive support from the French who appeared with a fleet off Kidwelly and Caernarfon at the end of 1403. Eventually a formal treaty of alliance was signed between Glyndŵr and Charles VI of France, who recognised his status as Prince of Wales. Glyndŵr would later write to Charles VI:

“Most serene prince, you have deemed it worthy… to learn how my nation, for many years now elapsed, has been oppressed by the fury of the barbarous Saxons; whence… it seemed reasonable with them to trample upon us… I pray and beseech your majesty to… extirpate and remove violence and oppression from my subjects, as you are well able to. Yours avowedly, Owain, Prince of Wales.”

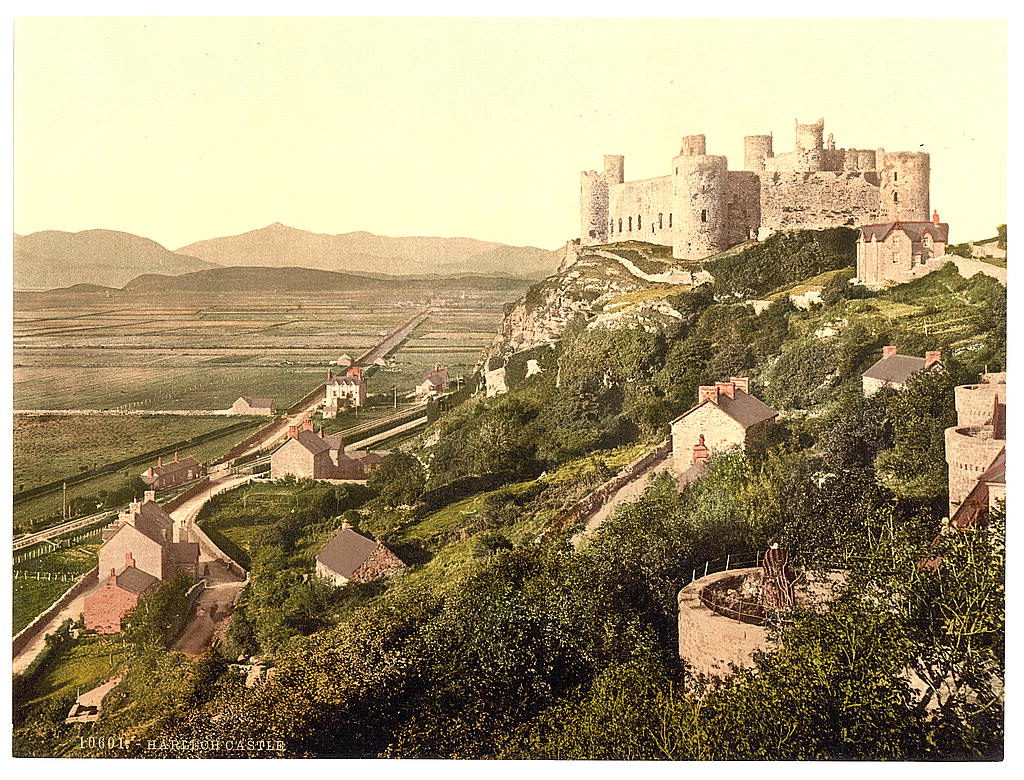

This letter showed that Glyndŵr saw himself and Wales as being worthy of recognition from the French king and he was getting close to his dream of independence. 1404 was the high point of the rebellion, with the mighty castles of Harlech and Aberystwyth being captured. Glyndŵr held a parliament at Harlech and it became the headquarters and court of the rebellion. It was the nerve centre for Glyndŵr’s vision of a free principality with an independent Welsh church and plans for the establishment of two universities. The capture of the two castles also confirmed Glyndŵr’s influence over large swathes of western Wales and endowed him with key coastal fortresses. At this stage, the Welsh rebel army numbered about 8,000 or more men, who continued to attack castles in southern Wales, including Cardiff and a raid into Shropshire. The inhabitants of Shropshire complained about the destruction wrought by the rebels and concluded a truce with “the land of Wales”. Most significantly, Glyndŵr was crowned as prince of Wales at Machynlleth in 1404 – his defiance against the English crown was now cemented.

The end of the revolt

France now sent troops to support Glyndŵr, that landed at Milford Haven in August 1405. A combined Franco-Welsh force then invaded England and encountered Henry IV’s army two miles north of Worcester. However, there was no battle, and the Welsh eventually went home due to a lack of food. Nevertheless, Glyndŵr’s financial position remained healthy thanks to the seizure of the king’s baggage train, which was loaded with provisions and jewels. Also, the rebels concluded a truce with the loyalist men of Pembrokeshire, which yielded up to £200 of silver.

1405 was also the year that the tide slowly began to turn in the English favour, starting with the Battle of Pwll Melyn on 5 May. The Welsh army, under the command of Glyndŵr’s son Gruffudd, attempted to capture Usk Castle but came up against a substantial English force that then proceeded to heavily defeat the Welsh. Sources are unclear, but it is usually said that the Welsh lost a huge number of men, among which was Glyndŵr’s brother Tudur, the renowned warrior Hopkins ap Tomos and John ap Hywel, an abbot who was the spiritual leader of the Welsh army.

Gruffudd was captured and imprisoned in the Tower of London. It is clear that the Welsh force was of considerable size and importance, as it contained key members of his family and entourage. Afterwards, 300 Welsh prisoners were beheaded by the English outside of the walls of Usk Castle, and this drastic measure showed that the English were determined to suppress the rebellion, as well as send a stern message to Glyndŵr. It is possible that the Welsh unwillingness to fight the English outside of Worcester stemmed from the defeat at Pwll Melyn. From this point onwards, the revolt began to peter out from a national perspective and Glyndŵr was increasingly on the back foot.

There were several reasons for the eventual Welsh defeat. Glyndŵr never had the universal support of his people, and although he attracted followers from prominent families, this was countered by other respectable dynasties and townsmen who were pro-English. Additionally, most Welsh attacks were little more than a show of strength, as they could not commit large numbers of troops for campaigns.

For their part, the English benefited from dominance of the sea and the fact that many of the English-built castles, with the exception of Aberystwyth and Harlech, often stood firm against Glyndŵr. Southern Wales and the border areas were used as headquarters from which to mount offensive sallies against the rebels. The English also reorganised their Exchequer to keep war finances steady and made their supply routes more secure. French support for Glyndŵr also began to fade after Henry IV negotiated a truce with Charles VI.

In 1406, the regions of Gower, Ystrad Tywi, Ceredigion and Anglesey all submitted to the English, and Prince Henry retook Aberystwyth in 1408. During the siege, cannons were used by the English in one of the first recorded instances of artillery fire in Britain. Harlech fell the following year and Glyndŵr’s family were taken to the Tower of London. Nonetheless, pacification was by no means complete.

The Welsh lightning strikes and guerrilla tactics enabled them to resist a final defeat and in 1409 Glyndŵr was reported to be devastating the countryside with a large band of followers. There was also another raid into Shropshire and in 1410, two Scottish merchants were imprisoned at Caernarfon on the accusation of attempting to aid Glyndŵr. As late as 1415, Welsh rebels were reported as being active in Merionethshire but of Glyndŵr himself there was now no trace. Henry IV died in 1413, exhausted by the stresses of his reign. Prince Henry succeeded as Henry V and began to issue pardons to former rebels and even to Glyndŵr himself. But the old warrior reputedly refused all offers of clemency and disappeared. There is no record of his death or burial in existence, but it is thought that he died around the year 1415.

In the end, the Welsh revolt was the last gasp of genuine freedom from England. Ironically, by the end of the 15th century it would be a Welsh dynasty, the Tudors, who would reign in England and the two countries were unified under an Act of Union in 1536. However, the Tudors largely ignored their Welsh origins and so it was Owain Glyndŵr, the last native Prince of Wales, who became a lionised icon. His long campaign of sieges, guerrilla attacks and battlefield victories were remarkable for their daring and support. What’s more impressive is that this Arthurian figure almost succeeded in achieving independence, and for that the Welsh have never forgotten him.

Tom Garner is Features Editor on History of War, he has an MA in Medieval Studies from Kings College London. For more on early Medieval warfare, subscribe to History of War for as little as £10.50.