He may be England’s most celebrated writer, but did Shakespeare hide codes and double meanings in his work to subvert the establishment during a time of religious turmoil?

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

Two guards grabbed him tightly and dragged him down a stone corridor, his shackled legs meaning he was unable to keep up the frantic pace they had set. He was determined to show no sign of weakness and tried to concentrate on the senses around him, such as the rats scurrying by his feet, the insects crawling on the walls and the warmth on his face from the burning torches that illuminated the short path.

How had things come to this? He was Robert Southwell, born into a good family and a man who devoted his life to God, being ordained a priest in 1584 in Rome. But what had been one of the best years of his life had also turned into one of the most bitter when later the same year, the ‘Jesuits, etc Act’ had ordered all Roman Catholic priests to leave England. They were given 40 days’ grace to do so and many of his friends had hurriedly scrambled their belongings together and fled the island nation for friendlier shores. These were difficult times to be a Catholic in England.

Pain ripped through his body as the guards swung him around a corner and flung open a new cell door for him. Looking at the horrible conditions his mind raced back. Damn that Henry VIII, he thought. Damn him and his desire for a male heir and his lust for Anne Boleyn that had seen him turn his back on the Catholic faith he had been brought up in. And damn that German monk Martin Luther whose actions had led the Protestant Reformation that had swept through Europe and ultimately been adopted throughout England.

Southwell was levered inside the cramped, dank space. He recognised it from the descriptions of others whose fate had brought them here; it was Limbo, the most feared cell within Newgate Prison, inside a gate in the Roman London Wall. The door closed and the guards walked away. His heart beating wildly with fear, he reflected on his decision to leave Rome in 1586 to travel back to England to work as a Jesuit missionary, staying with numerous Catholic families, thus becoming a wanted man.

Eventually, the door swung open and he was dragged out of his cramped cell. He could barely stand as he was taken to trial, hauled before Lord Chief Justice John Popham and indicted as a traitor. He defiantly laid out his position, admitted to being a priest and his sentence was passed. He was, Popham said, to be hanged, drawn and quartered. After being beaten on the journey through London’s streets he was forced to stand. His head was placed in a noose and he was briefly hanged. Cut down while still alive, his bowels were removed before his beating heart was dragged from his body and he was cut into four pieces. His severed head was held aloft. This was England in the late-16th century – Queen Elizabeth’s religious compromise wasn’t without its share of pain and suffering.

This was the world William Shakespeare lived in as he wrote his great works. He had moved to London from Stratford-upon-Avon in 1587, leaving behind his young family to pursue a career as an actor and a playwright with the troupe Lord Strange’s Men. He had married Anne Hathaway in 1582, when he was 18 and she was 26, and together they had three children, Susanna, Hamnet and Judith. But the lure of the stage had been too strong to ignore.

It had not taken Shakespeare long to make a name for himself. His first play, Henry VI, Part 1, written in 1591, made its debut a year later. It was successful enough to make fellow playwrights jealous. One of them was Robert Greene, arguably the first professional author in England. Unlike Shakespeare, he was university educated and urged his friends not to give Shakespeare any work, calling him an ‘upstart crow.’ Shakespeare was unmoved by such words. It would be, academics conferred later, a sign he was making his mark.

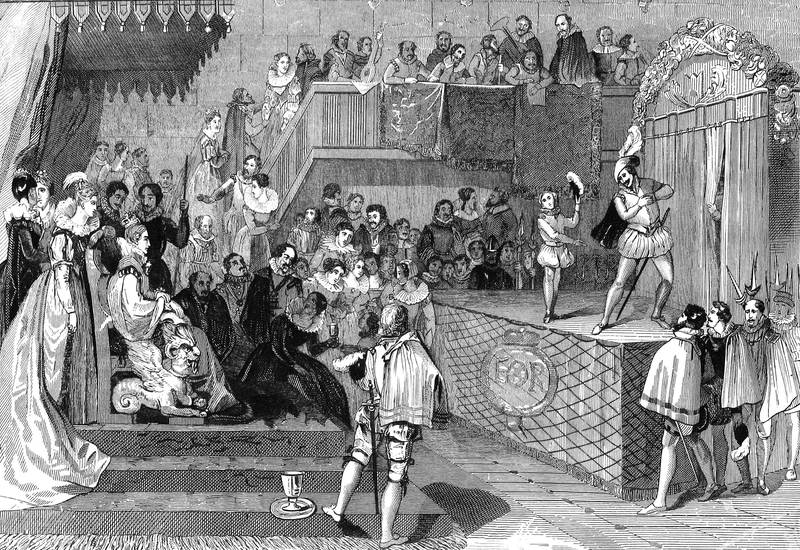

By 1594, he had written more plays and seen both Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrese published. He dedicated them to his patron Henry Wriothesley, the Earl of Southampton. He liked the Earl. Southampton was from a long Catholic dynasty and he appreciated poetry and theatre. When the theatres re-opened in 1594 following an outbreak of bubonic plague, he was keen to invite the Earl along. After all, Shakespeare’s new troupe, Lord Chamberlain’s Men, was becoming popular, with them even invited to perform in the royal court of Queen Elizabeth I. Shakespeare had also bought shares in Lord Chamberlain’s Men and was becoming a powerful and influential figure.

The Reformation had changed England’s approach to religion, moving the country away from its Catholic roots and into the arms of Protestantism. But it had not been as peaceful a transition as is sometimes painted. Protest leaders who encouraged more than 30,000 priests, gentry and commoners to demand a return to Catholicism in 1536 had been executed. Two years later, reformers had banished the cult of saints, destroying shrines and banning the population of England from making pilgrimages. Riots in 1549 were repressed in the most vicious of ways – the reformers would hang priests from church towers and lop off the heads of laymen who refused to obey the new order.

All this affected the Bard; he wasn’t writing in a bubble and nor were the actors who performed his work. Clare Asquith states in Shadowplay: the Hidden Beliefs and Coded Politics of William Shakespeare: “Shakespeare’s family are thought to have been Catholics […] his early years would have echoed to angry discussions of the impact of fines and imprisonments, the liberties taken by the Queen’s commissioners, the wreckage under Edward and the wicked errors of the old King.”

Speaking out against the establishment was hard – not least for those who wanted to keep their heads. Anyone wanting to put across another point of view had to be smart and Asquith believes the man who would go on to be England’s most celebrated poet and playwright rebelled and devised a secret code, inserting messages and double meaning into his writing. It isn’t as outlandish as it may sound; cryptology had been used since ancient times and there were examples of secret codes being used in this time period. For example, it is known that Mary, Queen of Scots used a cipher secretary called Gilbert Curle to handle her secret correspondence. It wasn’t entirely sophisticated, though, so her plot to overthrow Elizabeth was soon uncovered – Catholic double agent Gilbert Gifford intercepted letters that had been smuggled out in casks of ale and reported them to Sir Francis Walsingham, who had created a school for espionage.

For Catholics, certain words and key phrases stood out. For example, ‘tempest’ or ‘storm’ were used to signify England’s troubles, according to Asquith. So Shakespeare may well have been convinced he could change people’s view of the world by writing on an entertainment and political and religious level.

First he had to work out exactly what message he wanted to put across. Philip II of Spain, who had married Mary I, felt England’s Catholics had been abandoned and there had long been a promise that, if the Catholics bided their time, help would come. Relations between Spain and England had declined to an all-new low. This culminated in the sailing of 122 ships from Spain in 1588 with the aim of the Spanish Armada being to overthrow Elizabeth I and replace the Protestant regime.

The Armada was defeated but it had succeeded in creating further religious and political divisions, so the authorities were on even greater alert. Within this world Shakespeare got to work and, at first, kept things simple. “My reading is that the early plays were light, comical, critical and oppositional, written for Lord Strange’s Men”, asserts Asquith. The earliest plays addressed political reunion and spiritual revival. Their plots related to divided families, parallels for an England cut in two.

Asquith believes the Bard placed certain markers in his texts that signalled a second, hidden meaning. He would use opposing words such as ‘fair’ and ‘dark’ and ‘high’ and ‘low’: ‘fair’ and ‘high’ being indications of Catholicism while ‘dark’ and ‘low’ would indicate Protestantism. Asquith takes this as reference to the black clothes worn by Puritans and to the ‘high’ church services that would include mass as opposed to the ‘low’ services that didn’t. If this theory is true – a matter of some debate – then it enabled Shakespeare to get specific messages across, using characters to signify the two sides and by using words commonly associated with Catholic codes. For example, according to the theory, ‘love’ is divided into human and spiritual and ‘tempest’ refers to the turbulence of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation and the Bard used his own terms to disguise a message that was pro-Catholic.

At the same time, Shakespeare was operating in establishment circles. “He was drawn into the orbit of the court and wrote elegant pleas for toleration to Elizabeth, in the elaborate allegorical language she was used to”, says Asquith. But England was becoming more violent again. Shakespeare’s patron, the Earl of Southampton, rebelled against Elizabeth I, becoming Robert, Earl of Essex’s lieutenant in an attempt to raise the people of London against the government. The Essex faction had ordered a performance of the ‘deposition’ play Richard II just before the rebellion and Shakespeare’s company had their work cut out afterward denying complicity. The plan ended in failure in 1601, but in that same year, Shakespeare wrote Hamlet, encouraging action against unjust rule. “His more critical work supported the cause of the Earl of Essex against the [William] Cecil regime”, says Asquith. If this is true, then Shakespeare really was one of the defining rebels of the period.

Critics have said for decades that the writer was against populist rebellions and supported authority and the rule of law, “but with the recent reassessment of the extent of dissidence at the end of Elizabeth’s reign, Shakespeare’s Elizabethan work begins to seem more oppositional”, Asquith argues.

“What if the authority he upholds was not that of the breakaway Tudor state, but of the European church against which Henry VIII rebelled?” she asks. “What if he sympathised with the intellectual Puritan reformers, who felt secular monarchs like the Tudors had no business assuming spiritual authority over individual conscience? What if he, like so many contemporaries, opposed the destruction of the old English landscape, from the hostels, colleges, monasteries and hospitals to the rich iconography of churches to local roadside shrines and holy wells?”

It can be argued that the Bard personified England itself so that he could explore just why the ideas behind the Reformation had taken hold, presenting it as gullible and deluded, willing to turn its back on spiritual heritage, with the play Two Gentlemen Of Verona cited as evidence of this. The more elaborate plays retained the puns, wordplay and double meanings so beloved of audiences in Elizabethan times, but Asquith notes that some of Shakespeare’s characters came to be increasingly dramatic and allegorical; they had a hidden spiritual meaning that transcended the literal sense of the text.

When King James assumed the throne in 1603, Catholics had assumed that he would lend them greater support than Elizabeth, given that his mother was a staunch Catholic. But that was not to be and Shakespeare must have been well aware of a growing political and religious resentment against the monarchy, with a feeling of rebellion growing. His plays in this period became more cynical, which some have speculated was a consequence of the world he was living in.

Matters came to a head with an explosive event in 1605. Five conspirators, Guy Fawkes, Thomas Wintour, Everard Digby and Thomas Percy hired a cellar beneath the Houses of Parliament for a few weeks, spending time gathering gunpowder and storing it in their newly acquired space. Their plan was to blow the building sky high, taking parliamentarians and King James I with it. But their cover was blown and Guy Fawkes was taken away to be tortured into confession, the deadly rack being the instrument said to have broken him. He was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

At around the same time, Shakespeare wrote King Lear, Othello and Macbeth, all plays warning against unjust and persecuting rule, which many Catholics felt James I was guilty of. “My own theory is that Shakespeare, though not an outright rebel, used his increasingly privileged position to address the court and the crown, both Elizabeth, and James, on the issue of religious toleration”, Asquith asserts. “He protested against the persecution and injustice perpetrated in the name of the monarch, and pleaded for religious toleration.”

Such an assessment revises the prevailing thinking that Shakespeare wrote universal plays and avoided any topicality. Some literary scholars remain hostile to the idea that the playwright was involved in the volatile religious issues of the day, but could he really have ignored what was going on around him? It’s plausible that he wanted to do more than merely shake the literary world; he wanted to influence politics and religion, to affect his society.

When he sat at his desk, overlooking the squalid, filthy conditions of London, William Shakespeare may have been looking out at a more enlightened nation than ever before, but is was still a city and a country where the screams of religious and political prisoners filled the corridors of cramped jail cells as torturers extracted forced confessions. This sobering reality was a stark reminder of the perils of religious divisions that continued throughout Shakespeare’s life. Was it a society that he rebelled against in his own way? The final and definitive answer to that, like some of the great man’s work, is unfortunately lost to the ages.

Originally published in All About History 84

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!