How punitive criminal sentences, a gruelling journey and years of backbreaking labour forged the modern-day land down under

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

There wasn’t much in the way of mercy for a common criminal in 18th-century Britain. You could be branded or whipped for a relatively minor offence and for repeat offenders, the hangman’s noose awaited. The infrastructure of the criminal justice system was as outdated as the punishments it dished out, a relic of medieval times and unable to keep up with the burgeoning population and an exponential crime rate. A rudimentary police force was still over a century away, so with some help from the night’s watch, victims of crime were expected to obtain an arrest warrant, gather a mob and then apprehend the criminal themselves. Once the accused was handed over to the authorities they were expected to pay the cost of prosecution, which was often beyond the means of the working class. As if that wasn’t incentive enough to simply take it on the proverbial chin, if the victim pursued the criminal through court, they could face retaliation from members of the gang they belonged to. Unsurprisingly, a high number of crimes simply went unreported.

The courts themselves were also poorly equipped, with archaic legislation that allowed those cunning criminals that arrived at the court dock to easily slip through the fingers of the law. The biggest thorn in a magistrate’s side was ‘Benefit of Clergy’, a provision by which first-time offenders could simply quote the first verse of Psalm 51, beginning: “Have mercy upon me, O God…” to effectively get themselves off the hook. This was a throwback to a time when it was deemed that only those of the cloth could read and know the Bible, and thus were beyond the jurisdiction of anything but a church court. Although many 18th-century criminals couldn’t read, by rehearsing this verse they could easily avoid a brutal punishment altogether and walk away with their freedom and reputation intact.

As a result, the crime rate rose in Britain while death sentences became an everyday tool in a judge’s arsenal, used as a draconian way of reducing the number of criminals on the street as much as a deterrent. Even so, a state-sanctioned blood bath of hangings for the dozens of crimes that a criminal could receive capital punishment for was something the British government wanted to avoid. So, in 1718 and with the New World of America firmly in sight, the Transportation Act was put in effect.

Transportation was a legal way of sending convicted criminals abroad to labour in the new colonies. The act allowed for two categories of punishment for two different types of offence: for those that would normally receive ‘Benefit of Clergy’, the judge could hand out seven years of overseas labour instead of a branding or a whipping. Capital crimes could be repealed at the discretion of the judge and, if he was in a merciful mood, a death sentence could be reduced to a minimum 14-year transportation sentence. It solved the pressing issues of cheap labour in the new world, removed criminals from the streets and emptied jails; for the British government it seemed like the perfect solution. Thus Britain forged its new colonies on the blood and sweat of convicts. This was such a popular form of punishment that 50,000 people were transported to America from 1718 to 1786, and when the American Revolution broke out, making transportation to New England impossible, Britain didn’t consider changing its policy but simply looked to a vast wilderness brimming with opportunity on the far side of the world: Australia.

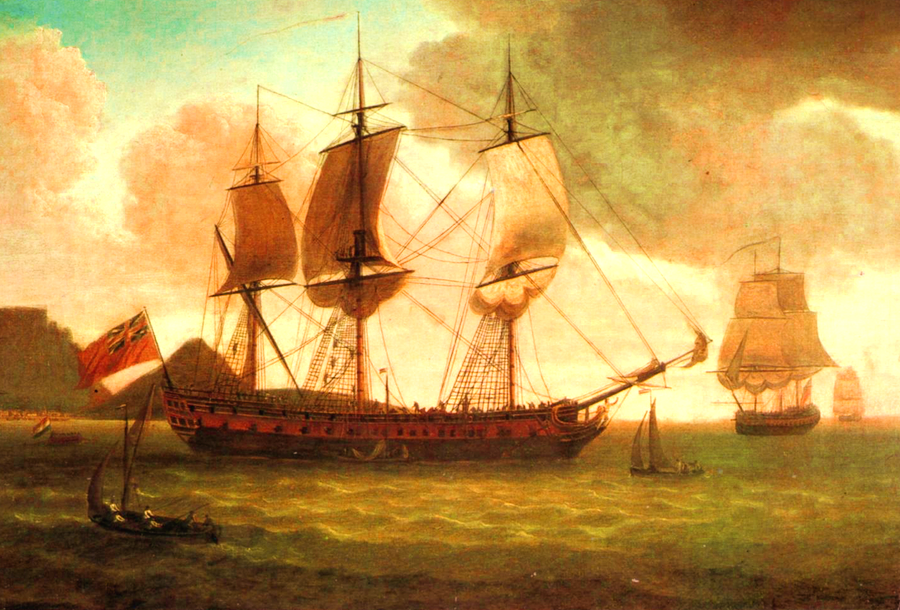

The ‘First Fleet’, as it’s now known, set sail for Australia on 13 May 1787 and consisted of 11 ships: two armed Royal Navy vessels, three supply ships and six criminal transports housing 736 convicts in total. The fleet’s admiral was Arthur Phillip, a working-class military man who had ascended through the merchant navy from apprentice at 13, before giving up his civilian rank to join the Royal Navy as a seaman two years later. He was a self-taught navigator and excelled in other maritime disciplines, which gave him a distinct edge over his peers and allowed him to take charge of his own fleet as admiral aged 50. He was also a disciplined, far-sighted and pragmatic leader who believed slavery would only hinder the progress of the new colonies, yet wasn’t afraid to use the hangman’s noose to make an example of those convicts who broke the rules repeatedly.

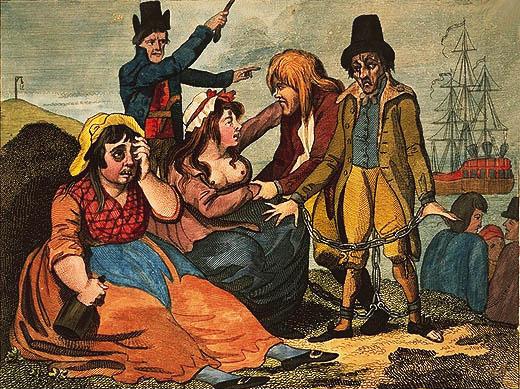

Only a few of those aboard had been given transportation sentences for violent crimes that would otherwise have necessitated a death penalty. Among those guilty of lesser crimes were 70-year old Elizabeth Beckford, given seven years for stealing a wheel of cheese, 11-year old James Grace, transported for stealing ribbon, and nine-year old John Hudson, a chimney sweep also given a disproportionately harsh sentence for common larceny. Admiral Phillip had hoped for tradesmen to set up the new colony but not only was he dismayed by the largely unskilled rabble he was presented with, he was appalled at the treatment the courts had meted out to the prisoners while their fate was decided.

Although the cramped conditions that awaited them below deck could hardly be considered comfortable, Philip had hoped that each convict was at least being given the best chance of surviving the journey that their ‘pardon’ afforded them: the sorry state that they were marched from the jail in suggested otherwise. Regardless of crime, age, ethnicity or gender, nearly all were malnourished, lice-infested and wearing barely enough in the way of moth-eaten rags to hide their modesty. It enraged Philip that not only was the government denying him the skilled labour he would need to effectively establish a colony, but the rag-tag dregs of Britain’s gaols had been half-broken before they had even left the shore. Nevertheless, he was neither going to be delayed nor disheartened, and so Philip saw the First Fleet through what would have been a distinctly unpleasant eight-month journey to a harbour 12 kilometres (7.5 miles) south of modern-day Sydney, stopping off at South America and South Africa along the way.

The last of the fleet landed at its final destination in Botany Bay relatively intact, on 20 January 1788. None of the ships had been lost on the journey and only 48 of the would-be colonists had died, a remarkably low statistic for the time. However, the new colony was nowhere near the paradise that explorer Captain James Cook, who charted the region on his 1772-1775 voyage, had painted. Cook arrived during the month of May and had named the natural harbour for the diversity of its vegetation, also noting its abundance of fish.

But at the height of the Australian summer when the First Fleet arrived, the land was withered and the stingrays Cook had talked about were nowhere to be seen. The shallow bay also prevented the ships from dropping anchor close to the shoreline, so conditions for a fledgling colony on shore were far from ideal. The water was mostly brackish, the bay’s topography would make it difficult to defend and the soil was poor with slim potential for growing crops from the grain they had brought with them. At least there were plenty of strong trees and the natives, an aboriginal clan called Cadigal, weren’t hostile. But the fear of attack from aboriginals or foreign powers looking to usurp his claim to the land led Arthur Phillip to search elsewhere. He took a small party of three boats north the next day to discover a much more suitable, sheltered site for a colony with fertile soil and fresh water. Cook had called it Port Jackson but hadn’t entered the harbour, so Phillip took the liberty of renaming it Sydney.

It wasn’t just the dregs of the prisons that had been upended into the First Fleet. One particular thorn in Phillip’s side was the prickly Major Robert Ross. The Scottish marine had a reputation for having a hair-trigger temper, but it wasn’t until Phillip was trying to set up the colony that he discovered just how insubordinate he could be. He refused to allow marines under his command to supervise convicts or to sit in court on convict trials, he was lazy, quarrelled with his officers and commanders alike and generally made Phillip’s job of governing the colony more difficult. Phillip had already instructed his lieutenant, David Collins, to take a small party of seven free men and 15 convicts to Norfolk Island, a small island 1,412 kilometres (877 miles) directly east of Australia. They arrived a month after the settlement of Sydney and over the course of a year, more convicts were sent to help with what appeared to be a promising industry.

Perhaps to avoid outright conflict as much as the need for a military presence on the island, Phillip decided to send the surly major over to Norfolk with a retinue of marines in 1790. It was not a successful relocation. Ross continued to argue with Lieutenant Governor Collins and his own men. He declared martial law for four months after the 540-ton HMS Sirius attempting to bring over a company of marines escorting convicts was wrecked on a coral reef. No lives were lost but the ship and all its provisions perished, which only piled the pressure on the islanders. In the space of a few years, Norfolk had turned from a small cottage industry settlement to an intensive labour camp worked by the worst of the Australian mainland’s criminals and overseen by military officers who proved difficult to manage. Ross was sent back to Sydney in 1791 and was promptly deported back to Britain after being relieved of his command. Even after Ross left though, Norfolk Island was still used primarily as a prison island for the worst of the worst from the Australian mainland. The treatment of its convicts under the command of Governor Darling became even more brutal.

The system that Arthur Phillip set up aimed to extract the best use of every convict. A few cursory details like their place of birth, religion and physical marks like scars or tattoos were noted to identify them, before they were asked about their previous trade and level of literacy to establish their vocation. Extra labourers, providing they worked well, were always handy but anyone with a trade was valuable. As the penal colonies of Botany Bay and Sydney spread into Australia’s rural regions, the trades of a Western civilisation became sought after. Now, not just carpenters, smiths and farmers were in demand, but housemaids, nannies, porters and other servants were required for the free migrants seeking their fortune in a new country. Regardless of their background, every convict was assigned a trade: the educated were freed from menial labour and got off lightly with the job of helping with the island’s administration, while the job of some wives and mothers was simply to help populate the colonies.

For those tasked with building the houses and infrastructure in the first few decades of the colonies, life was a shade tougher. Leg irons were widely used and the convicts’ overseers wielded their whips liberally. Back-breaking work building roads and bridges could last anything from 14 to 18 hours a day, seven days a week. Though the aim – ostensibly at least – was to reform these convicts into new colonists by the end of their sentence and there was even a chance for them to earn their freedom for good behaviour, there was no doubt they were being punished for their crimes.

Those transported for more serious crimes could face the death penalty if they were caught escaping, or at the very least face even harder time as colonists on Norfolk Island. Neither did those servants who were assigned to the households of the free migrants have an easy time of it. They were at the mercy of their masters and vulnerable to abuse.

Convicts weren’t completely without rights, though. The colonial government paid for their food and clothes, so if a convict’s master wasn’t feeding or clothing them properly, was giving them disproportionate physical punishment or not allowing them enough rest, the convict could have their complaint heard. If the defendant was found guilty, the convict could be reassigned to someone else and their former master or mistress could lose their right to have convicts work for them at all in the future.

The female transportees of Botany Bay and Port Jackson were treated separately from the men – the 120-strong convict roster on one of the six prison ships of the First Fleet was entirely female, for a start. When they arrived, they were sent to a prison called a ‘female factory’, where they laundered clothes, sewed and spun while they were awaiting assignment. Many of the women transported to Australia’s first penal colony brought children with them or had given birth at some point during the eight-month voyage. Their babies stayed with them until they were weaned, at which point they were taken away and put into an orphanage, where they could be claimed back once the mother had earned her freedom.

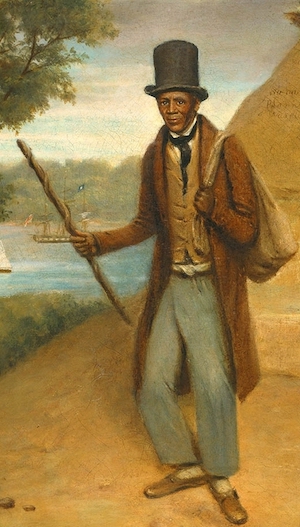

While life was hard for everyone when the Botany Bay colony was established, it was undoubtedly a better fate than some of the convicts would have met back in Britain. Records show that the quality of a convict’s food was much better in Australia than it would have been in Britain. For some, there were ripe opportunities abound in this new land, too. With Botany Bay and Port Jackson growing every year, free men and women began to migrate from Britain to seek their fortune and to take advantage of the cheap labour the penal colonies offered. If a convict behaved, adhered to the rules and served their time, they were free to go. They could buy their passage back to Britain if they wished, but most chose to stay and not just because of the high price of a ticket: the stigma of being an ex-con in Britain simply didn’t exist in this new land. Convicts had the opportunity to start again with a clean slate, take advantage of the many opportunities that Australia offered a free, white European citizen and even climb the social ladder – something unthinkable back on British soil.

Over the following 50 years, public opinion would gradually turn against the Transportation Act as it became thought of as a particularly cruel form of punishment. In 1850, 17 years after slavery was finally abolished, transportation to the growing colonies in New South Wales was also abolished. But by then, hundreds of thousands of Europeans had settled in the new land, many of them changing their names and leaving a dark past behind them, setting the future course of this new Australian nation.

Originally published in All About History 11

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!