The Guardian newspaper used to have a column called Reel History in which the writer and historian, Alex von Tunzelmann, reviewed films in the context of historical accuracy. In her articles a host of minor or major errors were exposed.

For one, Leonardo Di Caprio’s harrowing trek through the wilderness in The Revenant takes place on screen in a freezing winter, while the real person on whom the character is based made his real epic journey in late summer. For another, Benedict Cumberbatch’s Alan Turing in The Imitation Game probably never even knew the spy John Cairncross, let alone, as the film has it, covered up Cairncross’s treasonous activities. Ironically, von Tunzelmann was herself recently excoriated for her own alleged inaccuracy in a new film she has written about Churchill. According to historian Andrew Roberts “The movie is a catalogue of errors which paints an entirely false picture of Churchill…it’s a hatchet job of the kind the Nazi propaganda machine would have been proud.”

Strong stuff! Churchill himself had issues with cinematic falsehood. His objections were influential in securing the withdrawal from UK release of Errol Flynn’s 1945 war movie Objective Burma. What was wrong with the film? It gave American forces the credit and glory for victory against the Japanese in Burma which had actually been secured by British and Commonwealth soldiers. A Times leader thundered “nations should know and appreciate the efforts other countries than their own made to the common cause.”

Does it matter if historical facts are distorted? I think most people would say it was a question of degree. Misplacing Di Caprio in a snowy winter landscape to enhance dramatic effect is a mild and forgivable distortion. Implying falsely that the great Alan Turing colluded in espionage against his country is another matter. As for Churchill, one might think that his place in our pantheon of national heroes is secure enough to withstand a little filmic misrepresentation but allegations of gross inaccuracy are still disturbing if correct.

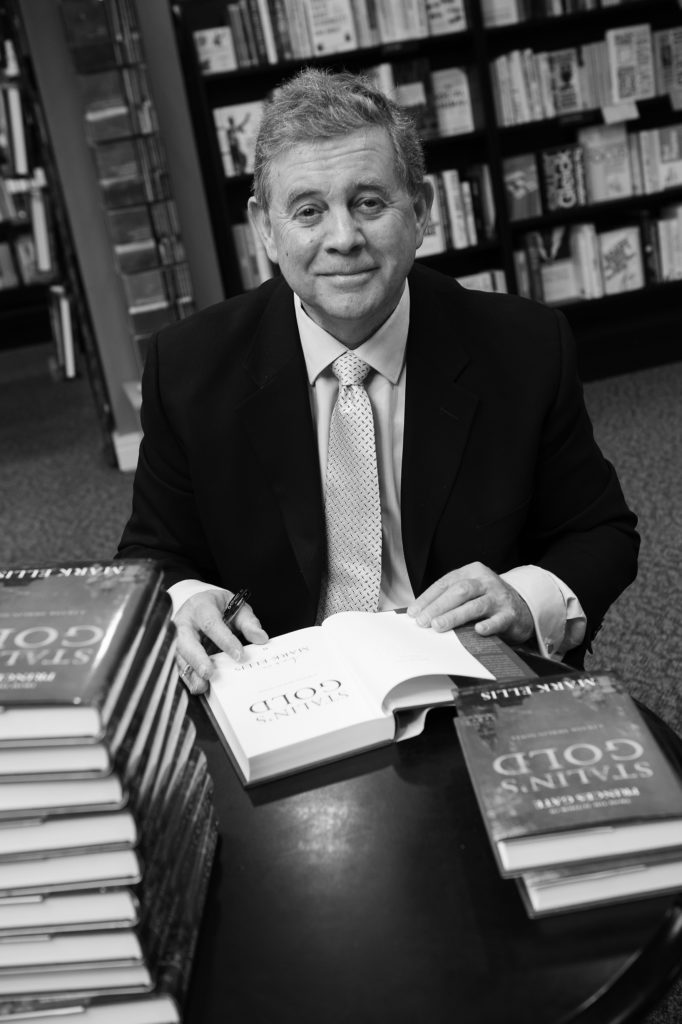

Historical accuracy in fiction is of keen interest to me as a writer of detective fiction. My period and place are World War II London and I try hard to get things right. Thanks principally to the wonders of the internet it is now possible to find out with relative ease the minutest of details about any day between 1939 and 1945.

What was the weather, how many bombs fell and where, which RAF planes were in the air, what was on the radio, at the pictures and the theatre? Details like these help to provide authenticity. People can get the hard facts of wartime life in history books but for a journey back in time to experience, for example, what it was like to pass the evening in an air-raid shelter in 1940, good fiction sometimes has the edge. To encounter a group of well-realised characters accurately reflecting the real people who endured Blitz nights on Underground station platforms may provide a deeper kind of learning experience than can the many excellent social histories of wartime London. Authenticity is essential to such fiction.

Good historical fiction can also open up people’s lives in a way not so available to the historian. To understand the real pressures and dangers of life as a spy in the war what better way to find out than through the novels of Alan Furst? To appreciate the absurdities of practical wartime soldiering at home and abroad what more illuminating than Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy. In some cases, even where the themes are on a very grand scale, fiction can be superior. Can there really be a better way to learn about Napoleon’s invasion of Russia than reading War and Peace?

By and large, I think most writers strive for historical accuracy. There have, of course, been many dreadful lapses. The WWII film U-571 tops the list for me. Following in Objective Burma’s shaky footsteps, the writers credited the heroic acquisition of the first naval German Enigma machine to the crew of an American submarine. It was really the British Navy who captured the machine and passed it to Turing’s Bletchley team for decoding, but many friends who’d seen the film wouldn’t believe me. ‘If it’s in a big budget Hollywood movie it must have happened that way’ they said. Thus the film betrayed the memory of brave people who did much to secure our victory.

I hope to avoid errors in my books, whether major or minor, and so concentrate hard on historical detail. My particular wartime detail may range from trifling matters like the day’s river conditions on the Thames or the evening wireless listings to the weightier matters of the defence of Britain, but the past is owed the truth, providing of course it can be found.

Merlin at War by Mark Ellis is out now (Hardback £12.99, London Wall Publishing).