The award-winning author discusses her book, Reckonings, and how many have still not been held accountable for their crimes under the Third Reich

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

Reckonings: Legacies of Nazi Persecution and the Quest for Justice looks to broaden the way in which the Holocaust is often remembered, expanding it not just from Auschwitz to the wider mechanisms of persecution in Nazi Germany, but also the longer tail of prosecution (or lack thereof) of perpetrators in the years following WWII.

It was the Wolfson History Prize 2019 winner with the judges stating; “Quoting many moving accounts from victims of the extreme cruelty perpetrated by the Nazis, Fulbrook moves through the generations to trace the legacy of Nazi persecution in postwar Germany. A masterly work which explores the shifting boundaries and structures of memory.”

We spoke with Mary Fulbrook about her important work and how the passing of time is affecting how we approach the Holocaust and the prosecution of those who aided and abetted it.

In the early years of prosecutions of the Holocaust, was a lack of witnesses ever a roadblock to justice?

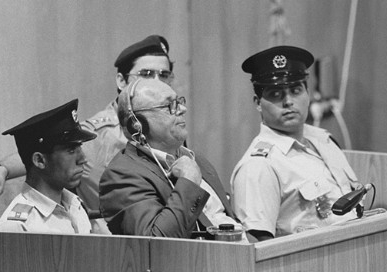

It changed over time. One of the things I did in the book was to look at trials over the decades and the need for witnesses has changed dramatically in the last few years since the Demjanjuk trials (John Demjanjuk was convicted in 2011 as an accessory to the murder of 28,060 Jews while working at Sobibór extermination camp in Poland). Witnesses for most of West Germany’s history, the Federal Republic, were used to try to show that a particular person had committed murder with particular intent or particular subjective motivation, and particular brute force, on a particular day at a particular time – and for that you needed witness testimony and it was very easily discredited in courts.

So where the killing machine was most perfect, as for example in Belzec, the extermination camp, seven out of eight SS guards who were prosecuted were acquitted. They had been so successful in killing everybody that only two people ever survived that camp (and one of them was assassinated in 1946), and so the SS guards just argued that they were only following orders and they were not murderers in the sense of West German criminal law definition of murder.

What changed at the Demjanjuk trial was that it now became sufficient to say somebody was part of the machinery in a place where mass murder was being carried out; and because they were actually functioning in that place at that time, they were also in some sense aiding and abetting the murders that were being carried out, and so you no longer needed this survivor testimony. So witnesses were absolutely crucial, but in two quite different ways. I think what has happened in recent trials is that witnesses have come simply to bear witness to the impact of that past on themselves or their families.

Was the legal system simply insufficiently equipped to handle some of these cases; did it have the precedent to lean on or the mechanics?

Well the West German legal system didn’t, the East German legal system and the Austrian legal systems did. And it was a political decision in West Germany to not adopt the Nuremberg Principles, which are appropriate to a system of mass murder, collective violence. And in part for good reasons, namely to show that what was committed under Hitler was a crime even then, but it had this perverse and ironic effect that you couldn’t actually then find people guilty if they were only following orders and herding people into gas chambers. You could put 300,000 people to death and not be a murderer, it was just a total distortion.

In East Germany former Nazi perpetrators were six or seven times as likely to be convicted as in West Germany and that was in part because they had a different legal system and in part because they were more determined to bring them to prosecution. There was a different mentality. The legal profession in West Germany was still very Nazified, so judges who had served in Hitler’s courts, went on to serve in the Federal Republic, which was not the case in East Germany. They had a total turnover of the legal profession.

And I think in Austria it’s different again, the legal system would have allowed easier convictions in terms of their particular legal system, but the juries were much more likely to acquit known Nazis so the acquittals began to be a public embarrassment and from the mid-70s they stopped trying to bring former Nazis to trial at all, because it was becoming so embarrassing that juries just acquitted them. So it’s a different reason in each case there.

In the case of West Germany what was the calculus for being more cautious in their prosecutions?

There were a number of different things going on. I think in the late 1940s to early 1950s when the Federal Republic is just being founded the Cold War plays an incredibly important role for America, particularly. The Western Allies see the threat of communism as greater than the importance of dealing with the Nazi past and so the Allies themselves start reducing sentences. People who were given life sentences have their sentences reduced to a shorter number of years and then there are amnesties; people are released early in the 1950s.

I think then the Cold War becomes important in a quite different way in the late 1950s/early 1960s, when East Germany starts using the fact that there are Nazis in high places in West Germany as a weapon in its Cold War propaganda against the West; and that stimulates West Germany re-opening the attempt to prosecute, particularly because the Statute of Limitations is beginning to run out. So there are big parliamentary debates about the Statute of Limitations and whether to extend it for the Nazi crimes of murder. But that gives an urgency to it in the early 1960s, which is when the Auschwitz trial starts being mounted. So political considerations change over time in different contexts.

An important area you touch on in your book is the way industries took advantage of the camps as a source of slave labour. Why do you think this has been largely sidelined and in many cases unpunished?

It’s one of the shocking aspects of all this; the notion of perpetrator was narrowed down to a lower class thug, preferably a Ukrainian or somebody else as a concentration camp guard, and the fact that then German businessmen got away with murder, literally. Friedrich Flick who when he died in 1970 was probably the richest man in Germany, one of the richest in the world, never paid a single cent of compensation to those few slave labourers who had survived; eighty percent of slave labourers he employed died on the job. Only twenty percent actually made it through and those who had survived long enough to try and receive compensation failed, and he didn’t pay a single cent.

I follow through some of the areas of slave labour in quite some detail in the book and I think that it’s absolutely shocking, that businesses, the common names that we still talk about today, the I.G. Farben successor companies, BASF, Hoechst and so on, made fortunes on the backs of slave labour and were never brought to account. I don’t know why that was so downplayed, but I think in the period of the economic miracle and Western determination to combat communism, getting the economy going again, preventing people from turning to communist causes and so on, were very significant political considerations in the 50s and 60s.

Do you feel that there are any gaps in our understanding of the Holocaust because there was a reticence to confront the full scale of it in the immediate aftermath of WWII?

There were things that I wanted to bring out in this book, which are not normally brought out because most books on the Holocaust treat the period as the period of the extermination of the Jews and then finish with liberation and maybe just a few years after the end of the war. What I wanted to do was to treat it on a much broader scale; the persecution of many, many other groups, including homosexual men, Roma and Sinti, Jehovah’s Witnesses, euthanasia victims and so on.

I wanted in the first part of the book to raise to attention individual stories, for example the suffering of gay men whose stories were never really told; and looking at the following decades, the fact that so many of these victim groups were still outcasts, still stigmatised and marginalised decades afterwards. Homosexuality was still a crime for the next quarter of a century and you get somebody released from a concentration camp going home and being met by the same bureaucrat who had sent him to the concentration camp still in the same office saying “hey, you’ve still got two years of your prison sentence and so off to prison with you”. It’s just shocking, stories like that.

I think it’s the late 1970s/80s that people really start wanting to hear the whole life stories of Jewish survivors, and also to understand that there were survivors who were persecuted for other reasons as well and who achieved incredibly late recognition. The ‘Gypsies’, Roma and Sinti, only became recognised in the 1980s. With the victims of euthanasia, many families still felt stigmatised and uncomfortable about the fact that they themselves bore a measure of responsibility for having put their relative into a sanatorium for the mentally ill or physically disabled and therefore felt partially agonised by their own co-responsibility for that relative’s death, and didn’t want to talk about it as it was too painful to confront. So it didn’t really come out in the open. And so many people were still in post in the sanatoria, for example, where the mass killing in gas chambers started in the euthanasia programme, you still had the same staff working in the clinics for decades after the war. You’re not going to put up a plaque outside your office saying ‘on this spot a few years ago I killed 10,000 people’. So memorialisation could really only begin to come after a whole generation had passed through.

You mention the treatment of gay men and one of the painful stories you tell in the book is of gay prisoners returning home and not being able to talk about why with their own families because homosexuality was still illegal.

Exactly, a terrible shame. Such an awful shame. I use the case of Pierre Seel quite extensively in the book because he was courageous enough to actually write about it and he’s written an absolutely heartrending account and he said for years afterwards he was so ashamed he couldn’t talk to his family, he couldn’t talk to anyone. He tried to get married and indeed had children, but ended up as an alcoholic and had a divorce, and it was only in the 80s that he finally thought ‘I must come out, I must tell this story’. I think one of the things I try to bring out in the book is that many survivors felt there was no one they could talk too, nobody who would listen, but at least in some survivor communities they felt they could talk to each other, and I think gay men felt particularly isolated in that respect.

Do you feel that we fully tackled the challenge of differentiating between the willing participants in the Holocaust and those who felt coerced to follow orders and do their jobs, even though they contributed to and committed crimes in the process?

That’s what my current book is about actually, the book I am writing now. I don’t think we have fully understood that yet and I think it is far more complicated than the old debates about consent and coercion, or terror and enthusiasm. We had very dichotomous debates from the 1980s onwards about whether the German people were frightened into obedience or were enthusiastic followers of Hitler, which is a very simplistic dichotomy. I think it’s far, far more complicated than that and I’m trying to explore that a bit in the work that I’m doing at the moment.

You use the concept of a mushroom cloud of memory around the Holocaust in your book. Could you explain that analogy a little for us?

Yes, it just came to me that there was this massive explosion of violence in a wide area across Europe, in a large number of places, which immediately devastates those communities who are immediately affected and involved in those areas, but what it seems to have done is then wafted across a far wider area. This is why I think mushroom cloud analogy is important because it’s affected and contaminated and tainted far wider circles across the world in different areas over time. Like many things it has a half-life and it’s a generational half-life and my feeling is that for my generation, which is the second generation if you like, the people born after the war but looking back at it, it’s very vivid, very immediate because we know people who are intimately affected.

I talk about communities of connection and identification and I think that you are intrinsically affected by it if you are personally connected with people who lived through it. I think for my children’s generation it is already a much more distant third generation and I think in the fourth, fifth and coming generations it will be past history, it will be dissipating in the wind. It will be of interest and continuing relevance, but in a different way. It won’t have the close personal impact, the emotional impact that it now does, so to some extent the mushroom cloud metaphor seemed to me really apposite.

As we move from one generation to the next, do we have the same emotional connection to these events?

I think the emotional agony is not the same the further away you get from the personal connection with it. I think you can have an emotional response reading any period of history. You can read about the plague or Black Death or 16th or 17th century history and feel agonised by the fates of our forebears, but the agony when you think about your own family or people you know and their families, it feels more personal. I think all history does elicit emotional connections and responses, otherwise we wouldn’t do history, it wouldn’t be relevant to us, we wouldn’t explore it. There are some parts of history obviously which are more like intellectual puzzles, but there are parts of history that are more or less evocative of emotional responses. I feel that this is something that has informed and structured us as people in this generation, which is different from looking back at previous eras where we don’t feel as intrinsically or personally connected to what happened.

Are we in any way better placed to look back and understand the motivation behind these horrific events with greater removal?

I think we’re differently placed because we have different interests in it. I’ve had many people writing to me about this book and many of them say ‘this helps me to understand my grandfather better’ or comments to that effect, and so for some people there is a need, on a personal level, to try and understand what a close relative had been up to or how they should think or feel about that relative. I think we will be differently placed when we’re trying to understand how a system of collective violence can develop, be sustained, pull so many people into it and wreak such incredible havoc and destruction, and that I think is the bigger lesson that is so important to come out of this.

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!