The scandal that brought down a US president and changed the political lexicon forever

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

With beads of sweat forming at his brow, the president of the United States of America looks straight down the lens of a television camera and says defiantly: “I’m not a crook.” The president, Richard Nixon, is in the middle of an hour-long televised question-and-answer session with over 400 journalists. That the leader of the world’s foremost superpower is forced to make such an astonishing statement shows the scale of a scandal that has spread like wildfire through the White House. It will lead to the first and only resignation of an incumbent president to date and become the defining political misdemeanour of the 20th century.

So seismic is Watergate that the last syllable will be added as a suffix to any public series of events deemed scandalous, yet the origins are seemingly small-fry in comparison to many political controversies – a burglary at the Watergate Hotel, the site of the Democratic National Committee.

At the time Richard Nixon delivers the quote, late in 1973, the walls are beginning to close around him, yet it will take almost another year for the president to tender his resignation following a ‘death by a thousand cuts’ that sees allies and aides resigning or cast ruthlessly aside. Days before Nixon resigns, beleaguered and facing impeachment, he consults an old colleague, Henry Kissinger, on his options. Seeing a broken man in torment at the prospect of only the second presidential impeachment and a potential criminal trial, Kissinger tries to console Nixon and even accedes to his request that the pair of them get down on their knees and pray. That it has come to this is an indication of the devastating nature of the revelations over a dirty-tricks campaign that struck at the heart of the White House.

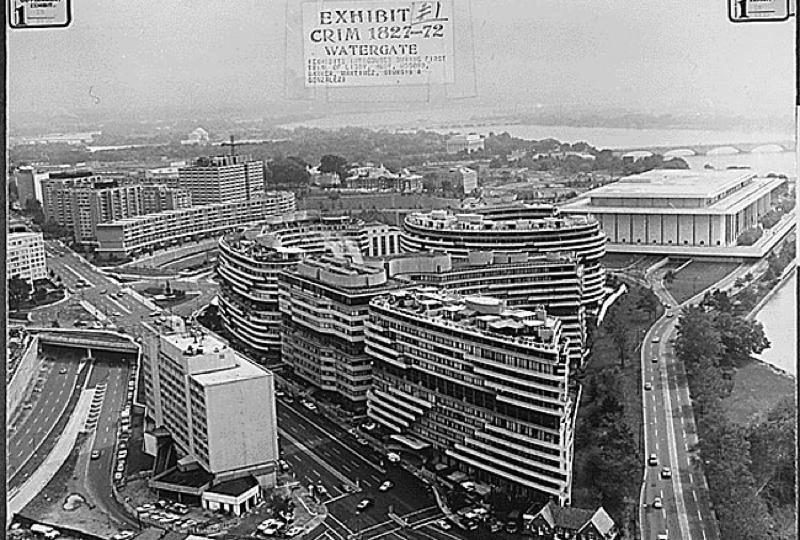

18 months earlier, on 17 June 1972, five men had been arrested by police on the sixth floor of the Watergate Hotel building in Washington, DC. Noticing that a number of doors have been taped open to prevent them from locking, a security guard called the police. All five were arrested and found to have connections with the CIA and a group that raised funds for the re-election of Richard Nixon, the Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP), often satirically abbreviated to CREEP.

Nixon is a familiar face, having been a vice president to Dwight Eisenhower between 1952 and 1960 and previously unsuccessfully fighting John F Kennedy for the White House. During a debate, the future president falls foul of a relatively new medium in political campaigning – while voters listening on the radio believe that Nixon has triumphed, television viewers are won over by JFK’s good looks and charm; they are equally dismayed by Nixon’s hunched shoulders, jowly appearance and sweaty brow. But, having narrowly won the presidency in 1968, Nixon wins by a landslide in 1972 and enjoys approval ratings of more than 70 per cent – almost unheard of for a president in his second term.

However, Nixon deploys an array of dubious techniques to smear opponents. The CRP becomes a de facto intelligence organisation engaged in dirty campaigns against potential rivals: bugging offices, seeking material that could be used against opponents and attempting to prevent leaks to the media. While the CRP is technically and officially a private fundraising group, its existence and true nature is known to several federal government employees and Nixon himself – while he is aware that the CRP gathers intelligence on his rivals and administration’s enemies, conversations reveal that he is either unaware of the scale of their activities or simply chooses not to know.

The five men arrested at the Watergate were likely there either to recover bugs that had been left on the telephone of senior Democrats or install new surveillance equipment but originally little significance is ascribed to the break-in. When the Washington Post’s rookie reporter Bob Woodward is sent to a local courthouse to cover the story, he discovers that the five men are no ordinary burglars, being found with unusually advanced bugging equipment and a surprisingly high-powered attorney. One of the men, James McCord, admits that he has previously worked for the CIA – Woodward connects him to E Howard Hunt and Charles Colson using phone books belonging to the men. Colson will claim that upon hearing of the arrests the day after they took place, Nixon hurled an ashtray at the wall in fury.

Hunt is another CIA operative with a colourful background – he had once been accused of involvement in the assassination of JFK; anecdotal evidence implies he may have been in Dallas at the time of the killing – and at the time was working for the White House Plumbers, a shadowy group that worked to prevent classified information being leaked to the media from the Nixon administration.

While the existence of the Plumbers – comprising a heady mix of CIA operatives, Republican aides and assorted security personnel – is known to Nixon, the extent of their activities is initially kept from him by senior staff. The group had come into existence from a desire to punish and undermine the Republicans’ enemies – a memo from 1971 suggested the group use any federal machinery “to screw our political enemies” – but the line between what constitutes enemies of America, the Nixon administration and the Republican Party becomes hopelessly blurred. Colson is a special counsel, essentially a lawyer, and Woodward realises that he, unlike Hunt, is a genuine link between the Watergate burglary and upper echelons of the White House.

In 1972, Woodward is teamed with another reporter, Carl Bernstein, and the pair is urged to develop the story by the Post’s executive editor. Woodward contacts an FBI source he has previously used, and using an elaborate system of signals and instructions he is told that the scandal originates in the White House. The source is referred to as Deep Throat.

When Hunt, G Gordon Liddy and the five burglars are indicted on federal charges relating to the burglary, Hunt demands money from the CRP and White House to support the seven’s legal fees – essentially hush money. They are all convicted in early-1973 and given stiff sentences, reflecting Judge John Sirica’s belief that the men are lying about their external help. The president announces that a full investigation has occurred and found no evidence of wrongdoing – while in fact no investigation has taken place. In his announcement, Nixon says: “I can say categorically that his investigation indicates that no one on the White House staff, no one in this administration, presently employed, was involved in this very bizarre incident. What really hurts in matters of this sort is not the fact that they occur, because overzealous people in campaigns do things that are wrong. What really hurts is if you try to cover it up.”

The words will prove to be prescient. Payments to the jailed men create a paper trail that implicates senior figures in the administration. Woodward deduces that the chief of staff, HR Haldeman and Attorney General John Mitchell are also implicated. Deep Throat claims the Watergate break-in was masterminded by Haldeman and also states that the lives of the two reporters may be in jeopardy: Woodward and Bernstein press on regardless and write a book, All The President’s Men, later turned into a film, about their experience of the scandal.

While Woodward and Bernstein are busy uncovering the paper trail to the White House, another revelation will prove just as disastrous for Nixon. James McCord sends a letter to Judge Sirica in March 1973, explaining that he has perjured himself, alleging orders from high up in the White House. Also in March, Nixon gets a lengthy rundown from John Dean on the scale of the dirty-tricks campaign and how the Watergate burglary came to happen. Nixon listens, appalled, as Dean recounts the web of deceit in which many of his staff are now trapped – Dean’s prognosis is grim: “We have a cancer, close to the Presidency, that’s growing. It’s growing daily. It’s compounding, it grows geometrically now because it compounds itself.”

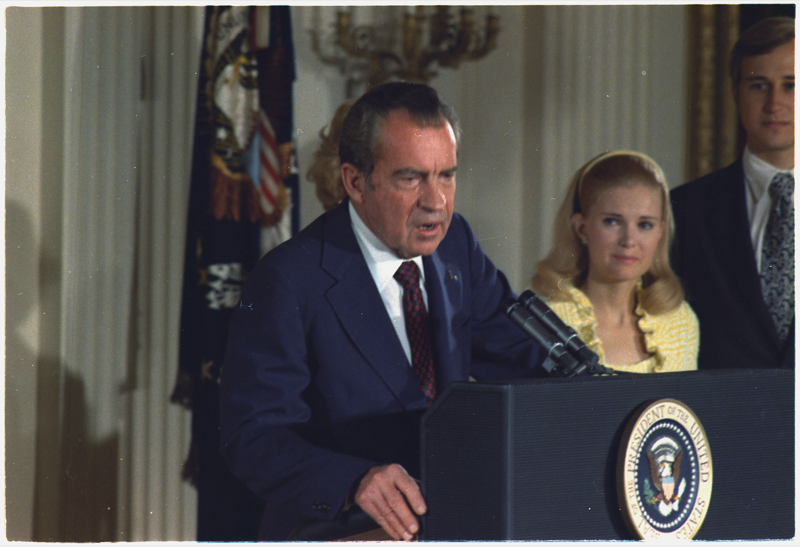

An exasperated Nixon sighs his way through Dean’s prognosis, which reveals illegal activities, blackmail and perjury on a grand scale. It is clear the chain is only as strong as its weakest link – and those are cropping up everywhere as the net tightens. Asked about his personal feelings on the matter, Dean replies he is not confident the administration can ride it out. Even Dean himself is starting to feel the pressure and can’t shake the impression that he is being set up as a scapegoat. He is probably correct: Nixon fires Dean, who turns star witness for the prosecution, and the president rolls the dice and gambles by disposing of some of his most trusted lieutenants, asking for the resignation of both Haldeman and Ehrlichman. Richard Kleindienst also resigns.

Coincidentally, at around this time, confirmation hearings begin for installing L Patrick Gray as permanent director of the FBI. During the hearings, Gray reveals that he has provided daily updates on the Watergate investigation to the White House and alleges that John Dean has “probably lied” to FBI investigators, enraging the White House. It is subsequently revealed that Gray has disposed of some of the contents of a safe belonging to Hunt – drawing the FBI into a web of deceit along with the CIA, the federal government and the Republican Party – forcing his resignation in April 1973. In just a few turbulent weeks Nixon had lost his three most trusted lieutenants, his attorney general and the head of the FBI. By May, more people disapprove than approve of Richard Nixon’s presidency and a month later the Watergate hearings are being televised; viewers see John Dean tell investigators that he had discussed the cover-up with Nixon at least 35 times. Although Nixon can plausibly deny knowledge of the CRP campaigns and protect himself by firing staff, things are about to get much worse for the president.

Nixon is a suspicious individual who has few real friends and sees conspiracies against him everywhere. Given to brooding behaviour and capable of vulgar outbursts and ruthless behaviour, the president will later acknowledge that the American people knew little of his real personality. This side of his personality was to be his undoing. Known only to a few individuals, Nixon has had secret recording equipment installed in the Oval Office, Cabinet Room and his private office in the White House. The resulting tapes are vital in proving his knowledge of – and active participation in – the Watergate cover-up and wider culpability in allowing his aides to commit behaviour both immoral and illegal.

Nixon has been at the sharp end of American politics for decades. He has made powerful friends and enemies alike and learned how to play dirty, even ordering tax investigations on Kennedy and 1972’s Democratic presidential candidate, Hubert Humphrey. On the tapes, Nixon is heard to remark: “I can only hope that we are, frankly, doing a little persecuting. Right?”

In the run-up to the presidential election of 1972, when it looks like Ted Kennedy – brother of JFK – will be a potential opponent for the 1976 election, Nixon and his aides attempt to use the Secret Service and Inland Revenue Service to spy on the Democrat senator in the hope of discovering material they can use to smear him. Such operations have been learned over 25 years in politics – Nixon smears his first political opponents as communists or communist sympathisers during his 1946 and 1950 Congress election runs. His nickname, Tricky Dicky, is devised during 1950 and he finds it hard to shake. Nixon also uses the shooting of presidential hopeful George McGovern in 1972 as an opportunity to place a loyal man within a security protection detail on Ted Kennedy. The spy, Robert Newbrand, is to pass information back to the White House. “[W]e just might get lucky and catch this son of a bitch and ruin him for ‘76”, says Nixon of Kennedy.

In light of what the president knows to be on the tapes, July 1973 brings a bombshell that Nixon instantly recognises as disastrous. The aide responsible for the president’s schedule and day-to-day archiving testifies that Nixon has had recording equipment secretly installed throughout White House offices. The ramifications are obvious, with the tapes laying bare just how widespread the use of dirty tricks are and how the orders frequently come direct from the president.

Archibald Cox, leading the hearings, instantly subpoenas the tapes. Realising the gravity of the situation, Nixon refuses the request, citing executive privilege and – for the next few months – begins a high-stakes game of bureaucratic cat and mouse in an effort to keep the tapes in his possession. In October, just days after losing his vice president, Spiro Agnew, to an investigation into past corruption, Nixon astonishes his advisors by ordering Cox’s firing – something only Elliot Richardson, the attorney general, could legally do.

The president, furious at Cox’s intransigence over refusing to accede to an offer to appoint a Democrat senator to listen to the tapes, rather than hand them over, makes it clear that he will accept the resignation of Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus if they do not sack Cox. On a night in October, dubbed the Saturday Night Massacre, Richardson refuses the order and promptly resigns. Having been given the same order by Nixon, Ruckelshaus also refuses and resigns, leaving Solicitor General Robert Bork to reluctantly carry out the order.

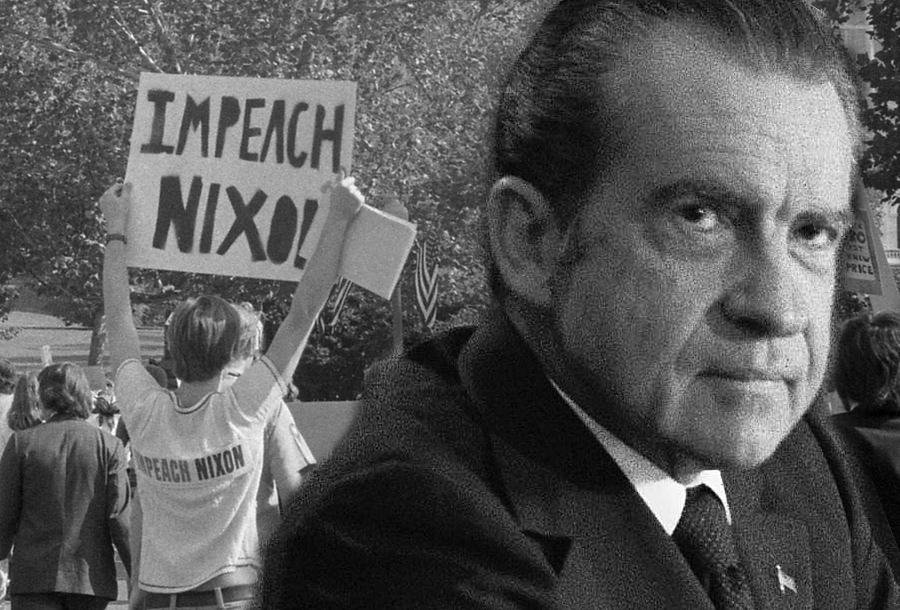

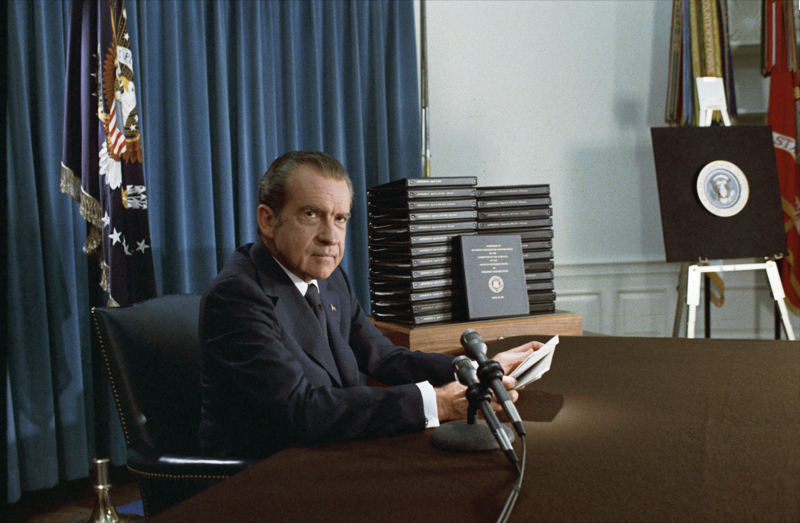

Public opinion quickly turns against Nixon, with protests greeting the president’s public appearances. In November, he goes on the offensive, delivering a televised question-and-answer session where he delivers the famous “I’m not a crook” speech. He claims the tapes will exonerate him, but knows that this is not the case and that his political manoeuvrings are merely buying time: his presidency is a busted flush. Nixon had earlier recognised the danger the tapes posed and asked Haldeman to dispose of them: “Most of it is worth destroying”, says the president. “Would you like – would you do that?” Haldeman replies in the affirmative but crucially is not as good as his word, perhaps believing that if he is seen to be responsible for destroying the tapes he would make the president bulletproof and seal his own fate.

In July 1974, having exhausted various means of preventing their release, including releasing transcripts and heavily redacted tapes, Nixon is ordered to give up the tapes to investigators and Congress moves to impeach the president. Any possibility that Nixon might hang on disappears in August, when a previously unheard tape is released. The evidence is known as the Smoking Gun tape. On the tape Nixon is heard advising Haldeman to advise the CIA to stop the FBI from investigating the Watergate break-in: “When you get in these people, when you… get these people in, say: ‘Look, the problem is that this will open the whole, the whole Bay of Pigs thing’ […] they should call the FBI in and say that we wish for the country, don’t go any further into this case, period!”

Opinion is divided as to what ‘the Bay of Pigs thing’ refers to, though the implication to the CIA is obvious – if they do not assist in the Watergate cover-up, sensitive information regarding the agency’s role in the aborted CIA-backed invasion of Cuba in 1961 will be released by the White House. The tape constitutes authentic evidence that the president was involved in the Watergate cover-up and attempted to pressure federal agencies into participating.

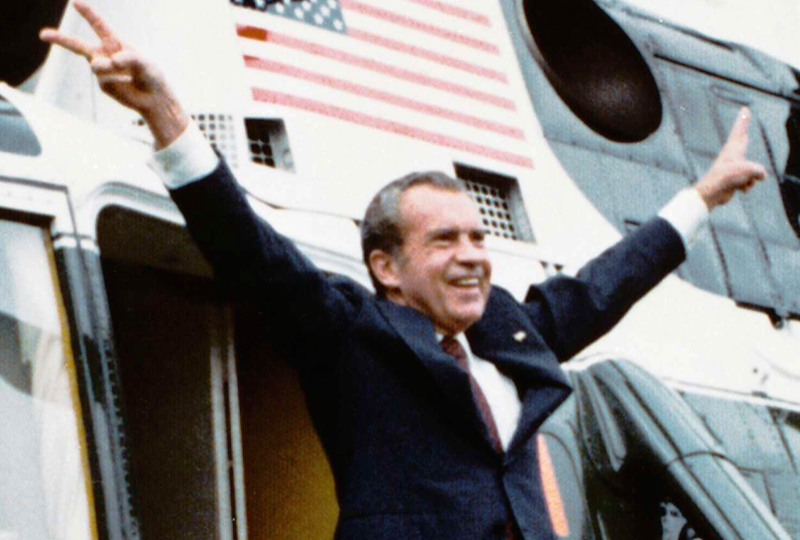

Senior Republicans gather to tell Nixon that he has no support in Congress. Ever the political survivor and having claimed that he would never resign, even Nixon realises that he has exhausted his options. The president promptly resigns, knowing that he will be impeached if he remains in office. His resignation speech is broadcast from the White House the night before he leaves for his home in California. Typically, his speech wrongfoots many, with allusions to the difficulties of office and oblique mentions of wrongdoing, notions of duty and vague expressions of regret.

Nixon also includes a lengthy summation of what he sees as his achievements in office, preferring them to discussions of Watergate – a trope that would become familiar in years to come. Nixon never escapes the taint of Watergate but he becomes a respected statesman on the American and global stages and wins acclaim for his domestic and foreign accomplishments. He is almost immediately pardoned by his successor, Gerald Ford, in a move that many decry.

Nixon avoids jail but the scale of wrongdoing – and the depth of the unpleasantness that modern US politics constitute – takes voters by surprise and reveals those at the top of government as venal, vulgar, deceitful and greedy. Most of all, it shows US presidents to be flawed and long after his resignation Nixon still inspires fascination.

Upon leaving the White House, Nixon spends most of his time at his house in California – driving to a small outhouse on his golf buggy every day to work on his memoirs. In 1977, short of cash and keen to rehabilitate his reputation, he agrees to the now-famous series of interviews with journalist David Frost. The trained lawyer and long-serving politician initially runs rings around the under-prepared Frost, but on the final day of interview the disgraced president finally opens up on the Watergate scandal: “I let down the country. I brought myself down. I gave them a sword and they stuck it in. And they twisted it with relish.”

The former president may have admitted some culpability but he never shakes off his ardent belief that the ends justified the means. Nixon had relied on a range of dirty tricks – many illegal – to claim power, and then affect change as he saw it. The apparently insignificant burglary that brought down the 37th president of the United States was just one of the ways that he bent the law – it’s just that this time, he got caught.

Originally published in All About History 11

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!