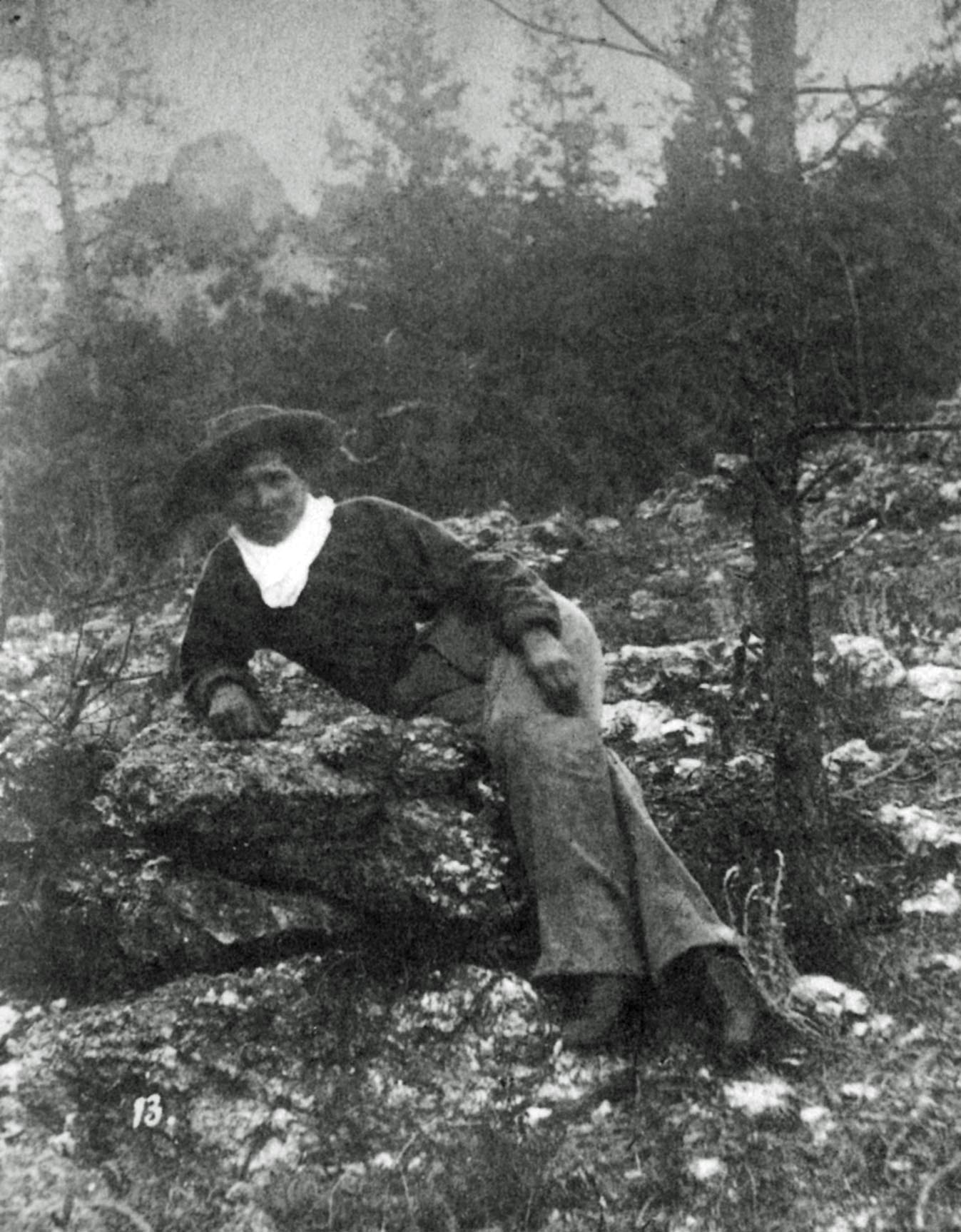

No other woman in the American west possesses a more enigmatic legacy than Martha “Calamity Jane” Canary. Between her birth in the 1850s and her death in 1903, Jane left a dizzying trail as she blazed around the west. She has been labeled a scout, freighter, and gambler, a drunken dance hall queen and prostitute. And though it is difficult to picture her in the domestic arena, Jane was also a mother.

To date, four children have been credited to the lady, although some of the claims have come from the children themselves. In 1941, Jean Hickok McCormick appeared in Billings, Montana. She said she was the daughter of Jane and Wild Bill Hickok, and was born in a cabin near Livingston, Montana in 1873. After a brief visit from Hickok, who then rode off into the sunset, a sea captain named James O’Neil happened to find her.

McCormick claimed that O’Neil offered to adopt her, taking she and her mother to meet his wife in Omaha. From there the O’Neils took the pair to the family home in Richmond, Virginia, and ultimately raised the Jean in Liverpool, England. McCormick had a lot of written “proof” too, which was largely believed by those who met her. In more recent times, however, Calamity Jane biographer James McLaird disproved McCormick’s claim by researching when and how her fantastic autobiography unfolded.

Then in 1996, a second daughter was revealed. She was Maude Weir, born in 1881. In her book Calamity Jane’s Daughter: The Story of Maude Weir, Weir’s own daughter, Ruth Shadley, said her family secretly knew that Maude’s real mother was Calamity Jane. But although there was an uncanny resemblance between the two, plus stories of Jane visiting the child, Shadley lacked any documentation to back up her claim.

In reality, Jane’s first verified child was born in November 1882 when she was living with rancher Frank King near Miles City, Montana. Area newspapers reported that Jane named the boy “Little Calamity.” A freighter named Evans recalled watching Jane smother the baby with kisses, calling him “Muzzie’s yittle snoozey [sic] darling.” Jane later told others that Little Calamity died. Within a month of the birth, newspapers tracked her to a hurdy-gurdy house in Livingston.

Last, there is Jessie—the most credible of Calamity Jane’s daughters. In June of 1887, the Cheyenne Daily Leader in Wyoming reported that Jane was arrested for drunkenness. In court she presented the judge with a doctor’s certificate indicating “she was in a rather delicate condition,” an early euphemism for “pregnant”. Several sources, including Jessie, verify the child was born on October 28.

For the next several years, various witnesses saw Jane, who towed Jessie around with her as she drank her way across the west. At Castle City, Montana in 1893, when Jane was running a restaurant, she had with her “the daughter of one of her soldier friends in Texas” who probably was Jessie. While at Castle City Jane went to Gilt Edge, some two hundred miles away, where she was jailed for being drunk. Upon being sprung, Jane whisked into Castle City, picked up the girl, and went on her way.

More concrete evidence of Jessie came from Charles Zimmerman, who remembered Jane and her daughter’s frequent visits to his family’s ranch near Billings, Montana in 1893. Zimmerman said that despite their closeness in age, he and Jessie “didn’t say much to each other.” In December, the Rawlins Republican reported that Jane visited town with “a little girl she had stolen.” The child was no doubt Jessie, who was next seen with her mother in Ekalaka, Montana in 1894 by at least two people.

When Jane arrived in Deadwood, South Dakota in 1895, she told others that she needed money to enrol Jessie in a convent school at Sturgis. Her friends held a fundraiser for her and the benefit proved a “howling success”—until Jane began treating her generous friends to drinks. By the end of the night most of the money had been spent, and Jane was “roaring drunk”.

That winter, writer M.L. Fox met Jessie when she interviewed Jane for an article in Illustrated American magazine. “I’m glad she’s come [home from school] while you’re here,” Jane told Fox, “fer I want you to see her. She’s all I’ve got to live fer; she’s my only comfort [sic].” Fox described Jessie as “neatly dressed” but “shy and embarrassed.” Yet she “had a bright face, and her manners were very good for one whose opportunities had been so few.”

Fox’s visit coincided with the few weeks Jessie actually attended St. Edward’s Academy in Deadwood. A classmate later remembered the children teasing Jessie about her mother, throwing stones at her while shouting, “Calamity Jane! Calamity Jane!” Jessie withdrew from the Academy a short time later, but in January of 1896, Jane was finally able to take her to St. Martin’s Academy in Sturgis. Jane had been hired to travel with Kohl & Middleton Dime Museums; as she purchased her ticket out of town she told railroad agent A.O. Burke she had enrolled Jessie in the school.

Jessie and Jane were back together when they arrived in Billings, Montana in 1898. Classmate Mary Connolly remembered Jessie, saying, “we all played hopscotch and jumped rope on the playground.” But mother and daughter eventually left town again. At Bridger, Montana, Jane moved in with a cowboy named Robert Dorsett.

In 1899, Dorsett took Jessie to live with his mother in Lewiston. But by January 1903 she was back with her mother once more, a fact verified by the Belle Fourche Bee in South Dakota. Six months later Jane visited friends in Deadwood, stating Jessie had married and was living in North Dakota with two children. Just weeks later, on her deathbed in Terry, South Dakota, Jane confessed that she and Jessie were now “estranged” and declined to say where her daughter was living.

Jessie later said that the Deadwood Chief of Police wrote her about Jane’s death in 1903. But thirty years had passed when she began making inquiries about Jane, whom she thought was her grandmother. Few could help her verify the truth, and Jean McCormick was of little help. By 1942 Jessie had changed her story, perhaps at McCormick’s urging. Now, she said, both Calamity Jane and another famed woman of the west, Belle Starr, were her aunts. Neither claim was true.

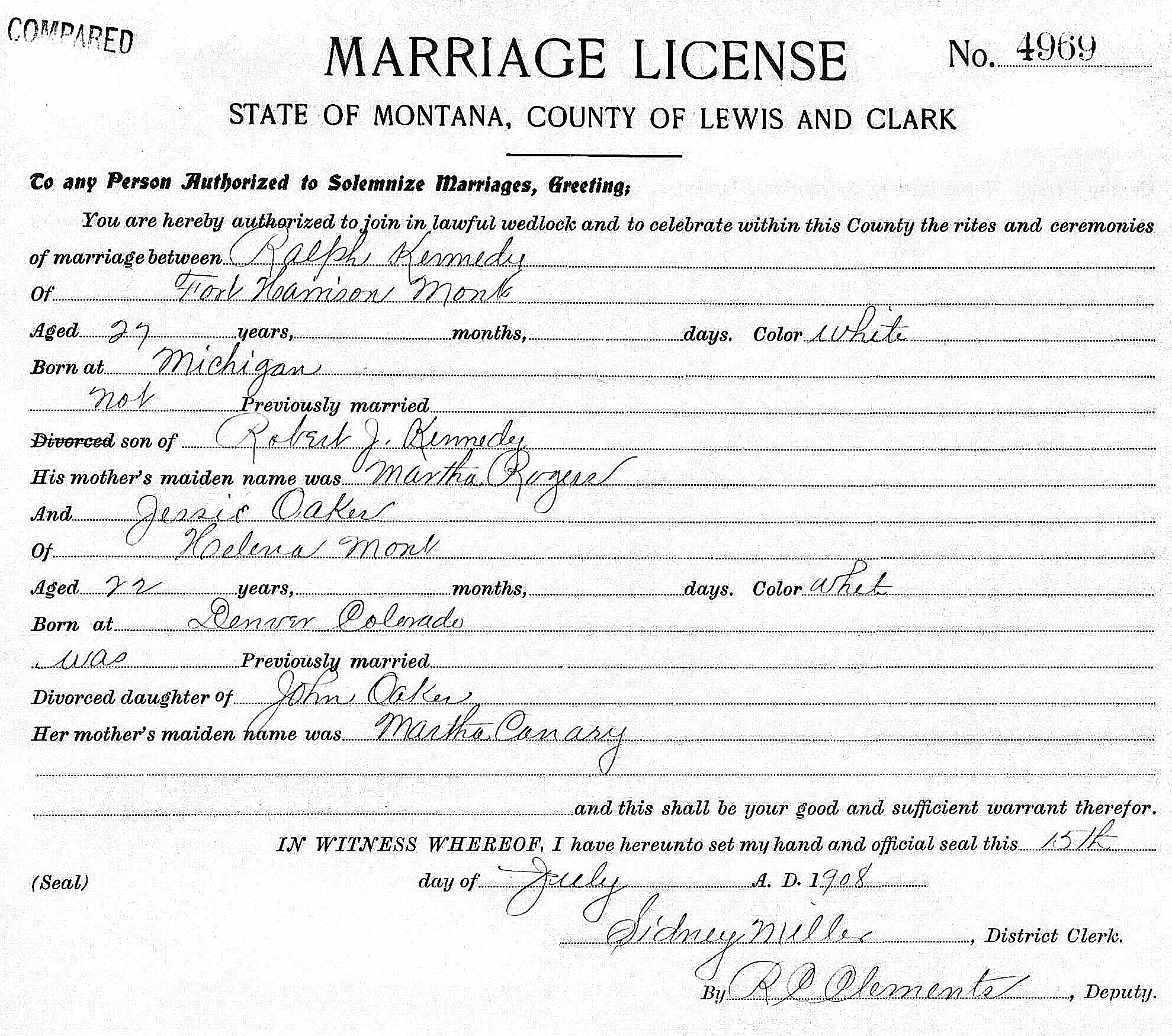

Author McClaird theorised that Jessie, who had no birth certificate, said what she had to in order to receive financial assistance at her last residence in California. She appears to have finally learned the truth by the time she died in 1980, for her death certificate correctly lists her mother’s maiden name as Canary. It was the last word on a true child of one of the wildest women of the west.

Jan MacKell Collins is the author of numerous books about the Old West, the latest is Lost Ghost Towns of Teller County. For more on American history subscribe to All About History for as little as £26.