His may be the greatest story ever told, but how do historians sort fact from fiction when it comes to Jesus?

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

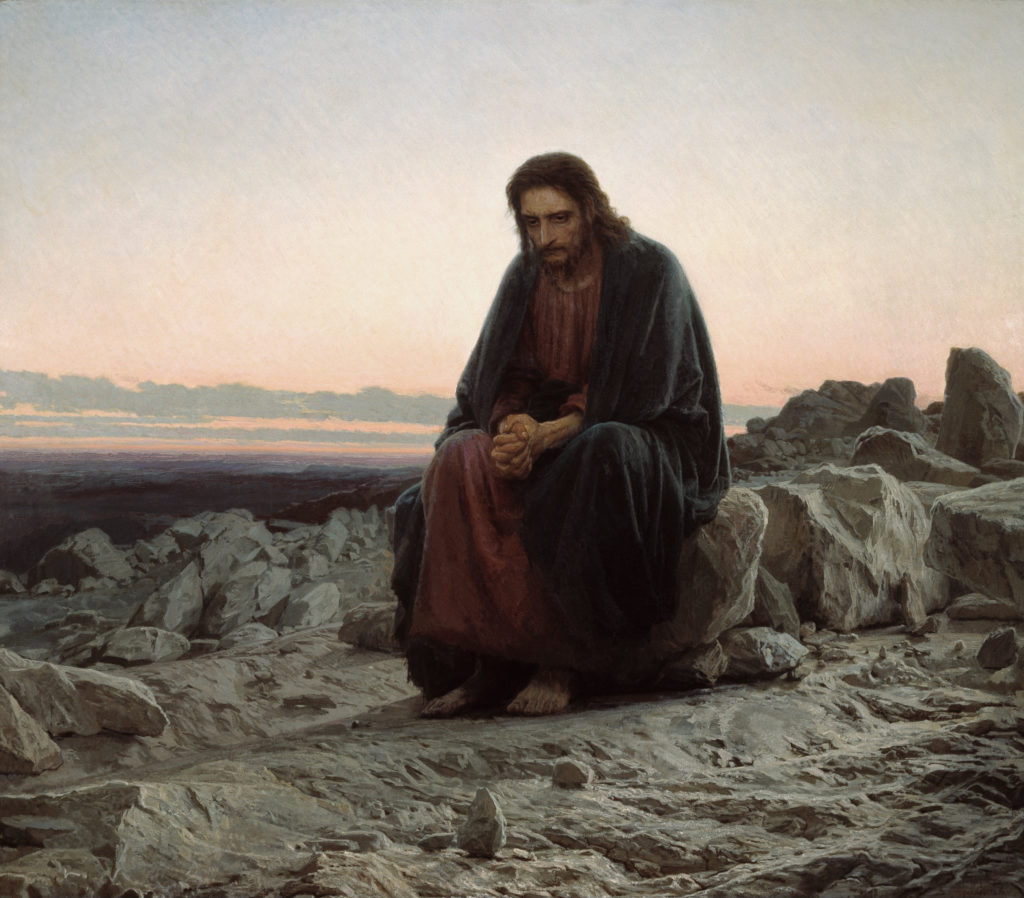

Jesus asks his followers in Matthew 16:15. It is a question they wrestled with and is still argued today. Believers may be able to approach the problem of Jesus via faith, but historians must use a different toolkit if they want to explore Jesus and his legacy. There is, and always will be, an impenetrable wall of mystery surrounding Christ the miracle worker as miracles are by their nature singular events that no amount of evidence will ever verify. Christ may be beyond the historian’s remit, but Jesus the man is not.

The search for the historical Jesus has been going on almost since the moment of his death. Today there are almost as many Jesuses as there are people looking for him. If you pick up any two books about Jesus you might think they were describing two different people. Marxists find a Marxist, philosophers find a philosopher, and modern Christians find a surprisingly modern Christ who agrees with all their own beliefs and prejudices. There are even those who believe that there was no historical Jesus, though few scholars hold this opinion.

Here we will look at how people have sought Jesus throughout history, what they have uncovered, and what evidence we can rely on when we assess the existence of this extraordinary individual.

The Early Texts

Like many of the great teachers, Jesus never wrote a book. We therefore lack direct access to his words and so must consider the accounts of others to fill us in on what he was like.

Historians would love to have multiple contemporary records of Jesus’s life yet that is unrealistic for the period. Even a locally important figure such as Pontius Pilate is only mentioned a few times by contemporary writers, and only a single partial inscription naming him has been found by archaeologists.

For a peripatetic teacher such as Jesus to receive even that level of attention would be remarkable. The earliest sources which give an account of Jesus come from the New Testament. Most scholars date the letters of St Paul to the 50s CE, just two decades after the death of Jesus.

Unfortunately the Pauline Epistles are written not with an eye to describing the historical Jesus, but to help settle theological debates within churches. From the references that are made to the life of Jesus we can glean such facts as Jesus was born, he taught, and he was crucified.

He makes references to Jesus’s brothers and describes how he met one of the brothers, James, in Jerusalem (described as a cousin or step-brother in some orthodoxes). Paul also knew of and had met some of ‘the twelve’ – the close followers of Jesus. Paul, who never met Jesus while he was alive, at least had access to eyewitnesses.

By far the longest accounts of Jesus’s life in the New Testament are the gospels. Despite the names traditionally attached to them (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) the texts are actually anonymous.

The dates of their composition are generally agreed as being between 66-70 CE for Mark and 90-110 CE for John. It is unlikely that the authors ever met Jesus but they may well have had access to reports from people who did. The gospel of Luke tells us: “Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the word. With this in mind, since I myself have carefully investigated everything from the beginning, I too decided to write an orderly account for you.” It would be tempting to take the gospels then as the authoritative and accurate chronicles of the life of Jesus.

While it is easy to talk about the gospels as one collection they offer a diverse set of viewpoints and often differ in their chronicling of the life of Jesus. The common nativity story known to us from many nursery school Christmas plays appears nowhere in any one gospel, but is constructed from aspects in Matthew and Luke.

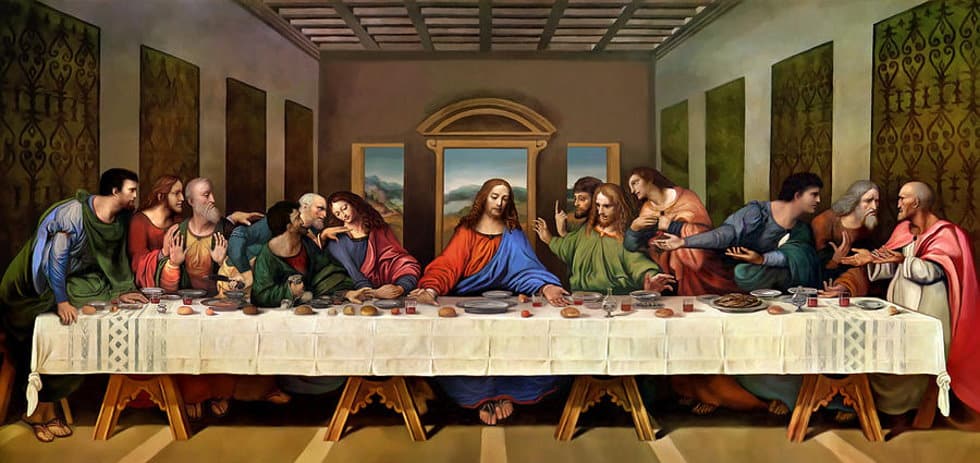

Where the gospels do include the same details they often disagree with each other, such as with the date of the Last Supper. Worse for historians is when the gospels do not agree with facts from other sources.

The gospel of Luke has Joseph and Mary travelling from Nazareth to Bethlehem to take part in an empire-wide census ordered by the Emperor Augustus, under the governorship of Quirinius, while Herod the Great was king. There is no other record of a census of the whole Roman world taking place at one time, and certainly none that would require people to return to far away towns because their ancestors lived there.

The main problem with Luke’s account though is that Quirinius was governor of Syria from 6CE, and Herod the Great had died in 4BCE. It would be impossible for Luke’s account to be accurate. Whatever the literary and moral qualities of the gospels, they must be viewed as historical artefacts and not history.

Outsider Sources

When studying the past it is always good to have multiple sources that have multiple views. Historians want accounts not just from supporters but from opponents too. The gospel writers clearly revered Jesus so it would be useful to see what those who did not worship him had to say.

All Roman sources on Jesus come from after his death, but there are some close enough in time to be useful to historians. Within 100 years of Jesus’s crucifixion we have potential mentions of Jesus by three writers.

Suetonius in his 121 CE history of the reign of the Emperor Claudius says Claudius expelled Jews from Rome “since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus”. The nearness of Chrestus to Christ has led many to identify the two figures, but we learn nothing from this reference except perhaps that there were Christians in Rome by that point. Similarly the famous 112 CE letter of Pliny the Younger where he asks the Emperor Trajan how to deal with Christians in his province is valuable evidence of the early church, but not about Jesus himself.

The historian Tacitus, when he recounts the Great Fire in Rome, describes how Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations “called Christians by the populace”. Importantly for our purposes he then describes their leader “Christus” who “suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus”.

We do not know the source of Tacitus’s information on the life of Jesus but he is a valuable outsider source even if the Pilate Inscription does call him a “prefect” rather than a “procurator”.

The longest account comes from the Jewish historian Josephus, writing around 94 CE. In his Antiquity of the Jews there is the following passage, “About this time there lived Jesus, a wise man, if indeed one ought to call him a man. For he was one who performed surprising deeds and was a teacher of such people as accept the truth gladly. He won over many Jews and many of the Greeks. He was the Christ. And when, upon the accusation of the principal men among us, Pilate had condemned him to a cross, those who had first come to love him did not cease.”

Josephus’s comment on Jesus, often called the Testimonium Flavianum, has been cast into doubt in recent years. There are those who think that this section of Josephus’s work was entirely concocted by later Christian copyists looking to bolster evidence for their beliefs. Some researchers however see a kernel of authentic testimony in Josephus’s writings. Perhaps Josephus did write about Jesus’s crucifixion, but later scribes glossed the text to make it more laudatory to Jesus. If this is the case it happened early, as Christian authors quote the passage in the 4th century CE. If the answers are not in the texts then other sources about Jesus had to be found.

Relic Hunters

Catholic altars have generally always contained relics – either some part of a saint’s body or something closely associated with them. The New Testament gives examples of people being healed just by touching the robe of Jesus so it was natural that followers would search out items that had been close to Jesus. Such a search, if able to provide physical evidence of Jesus’s life, would be valuable to historians. Perhaps the most famous early relic hunter was Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine. Constantine was the first Roman emperor to allow Christians to worship legally and he converted, on his deathbed, to Christianity. Once installed as emperor in 306 CE he gave his mother unlimited funds to tour the Holy Land in search of relics. Many sites still visited by Christians today, such as the Church of the Nativity, were first built by Helena.

According to legend it was while Helena was constructing a church over the site of Calvary that she discovered three buried crosses. To test which cross was the one on which Jesus died Helena had a sick woman brought to touch each in turn. It was contact with the third cross, which healed the woman, and Helena declared she had found the True Cross. A peer-reviewed journal today would be unlikely to accept such evidence. Other writers record how Helena found the nails used in the crucifixion and the seamless robe of Jesus.

The demand for relics only grew with time and proliferated to such an extent that it is now impossible to find any that are unambiguously genuine and shed any light on the life of Jesus. Fragments of the True Cross were so numerous that John Calvin declared in 1543: “If all the pieces that could be found were collected together, they would make a big ship-load. Yet the gospel testifies that a single man was able to carry it.” If historians were to seek physical proof of the life of Jesus they would have to wait for archaeological methodologies to improve.

Digging for Jesus

The spectacular monuments of Egypt sparked a rush among Europeans to see them, excavate new sites, and return with astounding artefacts in the 19th century. This boom created the first group of people who pursued archaeology in the first systematic way, if only haphazardly at first. From these beginnings other researchers moved into the Holy Land looking to locate the many sites mentioned in the Bible.

The first to survey locations in Palestine often made connections with New Testament sites on only the most flimsy of evidence, sometimes just on a feeling. Later archaeologists were able to locate important sites more accurately, even those doubted as real. The gospel of John mentions a pool at Bethesda with porticos and five entrances. Many questioned whether such a place ever existed, but in the 19th century a site very much as described was excavated. This helps place the narrative of Jesus’s life in geographical space. Other discoveries have revealed much about what it was like to be alive in 1st century CE Palestine. Much Biblical archaeology remains highly controversial though and forgeries have proliferated, including fragments of Dead Sea Scrolls that ended up in the Museum of the Bible.

Books in the Sand

Undisputed physical evidence of Jesus may not have been turned up by archaeologists but research both in Palestine and other places has turned up a wealth of rediscovered written material. The New Testament as we have it today is a collection of texts written by different people, in different places, at different times. To get to the currently accepted collection of texts took centuries of debate within the church and many, many other writings were excluded. Simply because those in the past did not accept them as inspired does not necessarily mean they are of no use to historians today.

These Apocryphal texts, as those not included in the Canonical Bible are called, offer some startlingly different views of Jesus. The Infancy Gospel of Thomas, dating from the 2nd century, features a young Jesus who causes the death of a playmate and withers another child, though he does restore them in the end. It is easy to see why such a text was left out of the Bible but that does not make all such apocrypha useless.

Recent efforts to get to the true historical Jesus have used close textual criticism. By comparing texts, canonical or otherwise, scholars are able to make judgements about the historicity of the events and sayings they describe. Several criteria have been suggested for seeking truth in Biblical texts. The criterion of multiple attestations

means that if several sources that do not rely on each other both say the same thing, then it is more likely to be true.

The criterion of dissimilarity says that if an act or saying of Jesus is different from what you would expect a 1st century Jewish teacher to say then it is more likely to be genuine. There is also the criterion of embarrassment. If a source is pro-Christian and yet says something which seems to harm the Christian argument, then it is more likely to be referencing a historical fact.

A close reading of the texts can turn up interesting features that may point to authenticity. Some parts of the gospels, written in Greek, make reference to the Aramaic which Jesus and his disciples spoke. In the gospel of Mark, Jesus is said to have raised a girl from the dead by saying “Talitha koum!” the gospel writer then glosses the Aramaic for his audience saying “which means ‘Little girl, I say to you, get up!’”. The other gospel writers give similar translations too which suggests a number of stories about Jesus were originally told in Aramaic, placing them in the cultural situation where Jesus lived.

“Who do you say I am?”

Who then was the real Jesus? It can sometimes look as if 2,000 years of work have left us little better off than those in the decades immediately after his death. Like Pilate we must ask “what is truth?”. All historical knowledge is a series of probabilities. The stronger the evidence the

more probable something is to have happened

in the way we believe.

For Jesus it seems that the most anyone can say with certainty is that a man called Yeshua was born around the turn of the 1st century, was a teacher who had several disciples, travelled around preaching, caused some trouble in Jerusalem, and was crucified around the year 30 CE. All other facts of his life must be determined on the balance of the evidence available to us.

Whatever we make of Jesus’s life we can be sure his remarkable afterlife will continue as long as there are historians to argue the case.

[Banner image: Jesus and his Disciples on the Sea of Galilee by Carl Oesterley (Image source: wiki/Dorotheum)]

Subscribe to

All About History now for amazing savings!