Viceroy’s House portrays the moment that Lord Louis Mountbatten arrives in India as Viceroy, with his wife, Lady Edwina. His mission is to hand over India, but to do so in an orderly manner that serves British interests. The Viceroy House, an impressive complex completed in the 1920s, has a vast staff, made up of a cross-section of the population of the sub-continent, and here, ‘below stairs’, is the fictional star-crossed affair of Jeet, a Hindu, and Aalia, a Muslim. At first, the troubles affecting parts of India seem far away, but, as the story progresses, events begin to crowd in on the Viceroy’s household, and good intentions are overwhelmed by the scale and tempo of approaching independence; and violence.

Viceroy’s House portrays the moment that Lord Louis Mountbatten arrives in India as Viceroy, with his wife, Lady Edwina. His mission is to hand over India, but to do so in an orderly manner that serves British interests. The Viceroy House, an impressive complex completed in the 1920s, has a vast staff, made up of a cross-section of the population of the sub-continent, and here, ‘below stairs’, is the fictional star-crossed affair of Jeet, a Hindu, and Aalia, a Muslim. At first, the troubles affecting parts of India seem far away, but, as the story progresses, events begin to crowd in on the Viceroy’s household, and good intentions are overwhelmed by the scale and tempo of approaching independence; and violence.

Lord Ismay, the Viceroy’s Chief of Staff who is represented in the film, recorded:

“Before I left England, I was doubtful whether a mistake had not been made in fixing the date for the transfer of power to Indian hands as early as June 1948. I had been in India for a week before it was borne in on me that so far from being too early, it was too late. I got the impression that in a very short time we should find ourselves still saddled with tremendous responsibilities, but equipped with no power wherewith to discharge them. The few British officials that were still in service were at the end of their tether . . . British arms were represented by little more than token forces.”

There were many issues within the final weeks of the transfer of power. There’s the accusations that the British are leaving a country still in poverty, with the work of development still half-done. There is a sense that the British give their preference to Mohammed Ali Jinnah and the Muslim League to create a greater allegiance amongst Muslims against the Soviet Union. It was a process carried out in great haste, although the film makes it perfectly clear that Britain had simply run out of options: it couldn’t get any agreement from either side, Hindu or Muslim, and it had run out of time, goodwill and manpower to hold on any longer.

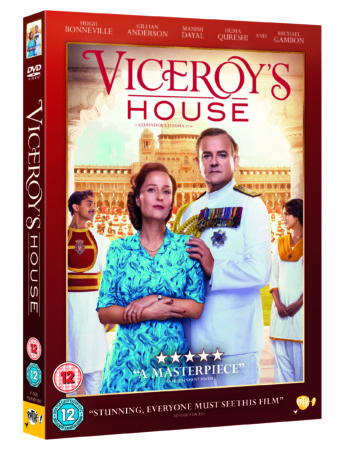

The British had favoured a gradual transfer of power to maintain control. Attempts to introduce local governance in the inter-war years was seen by Indian nationalist leaders as a deliberate attempt to avoid progressing to full independence. Consequently, there was widespread civil unrest. Nevertheless, Hindus and Muslims were brought into the Indian Civil Service, there was development in civil society, professional training in the medical services, the appointment of Indian officers as part of the ‘Indianisation’ of the army, and expansion of the Indian service sector in the economy. In Viceroy’s House, which releases on Blu-ray and DVD 7th August in case you are yet to see it, we see the results of this Indianization underway.

The outbreak of the Second World War interrupted the gradualist approach. The British government had initially ignored the Indian National Congress and then, through the Cripps Mission of March 1942, offered places in the Viceroy’s Council, with promises of representative government and dominion status after the war. The British also insisted on the protection of minorities’ interests and the freedom for individual provinces to elect to join an Indian Union, which was a way of preserving the Princely States. Incensed by the lack of progress, fearful that Muslims would stay outside a united India, and inspired by Mohandas Gandhi’s campaign of non-cooperation, the Indian National Congress had launched a ‘Quit India’ movement during the war. It was forcefully contained, but only with great difficulty, and national sentiment hardened. Many nationalists courted imprisonment as a badge of honour, and in the film, Aalia’s blinded father speaks proudly of his resistance.

The British anticipated that the end of the war would mean a return to widespread violence that the Indian Army would be unwilling and perhaps unable to contain. Army Headquarters informed the Military Secretary:

“It is fair to say that, as the war draws to its close … the general I[nternal] S[ecurity] position is bound to deteriorate, as interested parties begin to prepare (as they are now preparing) for the eventual struggle for power.”

The additional pressure was that thousands of Indian soldiers were being demobilized after the war and were in need of work. In the film, this includes Aalia’s betrothed ex-army fiancé.

Back at the political level, Jawarhalal Nehru is portrayed in the film as an intense figure, prepared to give Mountbatten a chance to prove British sincerity about independence, but clearly serious and determined. While Nehru asserted Congress, Jinnah eventually tired of the talks and declared a Direct Action Day on 16 August 1946. Designed to prove that Muslims’ interests had to respected, the demonstrations merely deepened existing communal antagonism with Hindus. Some 4,000 were killed in the fighting. The increasing violence deepened division, with grave consequences for our young Indian couple in the film, but with even more shocking effects in real life.

Before Mountbatten’s appointment, the British had drawn up a secret plan for the rapid withdrawal from India ‘in the event of a political breakdown’. Only a select handful were party to the plan, and, in the film, there is a dramatic moment where Mountbatten is made aware of a comparable, pre-determined secret ‘partition plan’.

Mountbatten had very little room for diplomatic manoeuvre and even his reputation for charm and goodwill was unable to overcome the intransigence of the national movements. Wavell had noted, before Mountbatten’s arrival:

“The machinery on which our control in India has depended is rapidly running down… [the Indian Civil Service] have always been few in number and their effect has depended on their prestige, their confidence that they can rely on the support of the government, and their solidarity.”

The film captures perfectly the transfer of allegiance from Britain to communal preferences, with disputes erupting with ever greater frequency within the Viceroy’s house.

Mountbatten’s predecessor, Wavell, when he left, had estimated that Britain would only be able to enforce its will for another 18 months at best. In London, the government was soon brought to the same judgement. The Cabinet concluded on 10 December 1946:

“One thing was quite certain viz., that we could not put back the clock and introduce a period of firm British rule. Neither the military nor the administrative machine in India was any longer capable of this.”

Wavell had written:

“The administration has declined, and the machine at the Centre is hardly working at all now, my [Indian] ministers are too busy with politics. And while the British are still legally and morally responsible for what happens in India, we have lost nearly all power to control events; we are simply running on the momentum of our previous prestige.”

Attlee instructed Mountbatten that the ‘definite objective’ of the government was ‘to obtain a unitary Government for British India and the Indian States, if possible within the British Commonwealth, through the medium of a Constituent Assembly’. Mountbatten was unable to get any agreement. The Cabinet reported in May 1947 that: ‘the refusal of the Muslim League to participate in the work of the Constituent assembly destroyed any possibility that the Cabinet Mission Plan [outlined above] could be successfully put into effect’. There was ‘no prospect of a Union of India’. The British were aware of ‘the difficulties and dangers necessarily inherent in any scheme of partition [since] the situation in many parts of India was already highly inflammable’. There was a significant risk of bloodshed in the Punjab, and the Sikh community would be divided. The logistical and administrative complexity of dividing the country between the successor states, as well as partition of trade, finance and industry, was enormous. In Viceroy’s House, there are scenes of absurdity in that allocation. The problem was that Britain had no power left to control events or to ensure equity. Even Gandhi’s calls for compromise went unheeded. His heartfelt appeal for conciliation, after independence, cost him his life.

Mountbatten was instructed to ‘thrust upon the Indians the responsibility for deciding whether or not India shall be divided and in what way’. Based on self-determination, it was fully expected that a bifurcated Muslim state, split between the north-west and Bengal, would be the result. In common with other parts of the British Empire, many in government hoped that the economic demands for co-operation between the new states would force them to work towards some sort of federation. Realising the situation was slipping out of control, and desperate to halt the violence, Mountbatten announced in June 1947 that the date of the transfer of power would be brought forward to August, barely three months away. He made a public appeal for ‘a reasonable measure of goodwill between the communities’. Admitting that he had failed to get agreement for the Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946, he believed the only alternative to coercing Indians into a single state was partition. He stressed his desire to avoid worsening the plight of the Sikhs of the Punjab by involving them in the boundary commission and expressed his view that he could not wait until the Constituent assemblies had completed their work on the details of the transfer. Instead, everything was to be ‘transferred many months earlier than the most optimistic of us thought possible, and at the same time leave it to the people of British India to decide for themselves on their future’.

By far the most depressing episode of the entire transfer was the severe loss of life in the Punjab (which affected the family of the film maker directly) and in Bengal. Increased rivalry between the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League had fuelled communalism to a pathological degree in some provinces. Fears and rumours stoked the antagonism, and when the partition was implemented in the autumn 1947, panic caused a flight by communities who realized they would be on the wrong side of the border. Gangs rushed in to seize land or to avenge themselves against the rival community, and news of deaths inflicted by one side merely encouraged the other to take reprisals. Estimates are that half a million were killed during the widespread violence of partition. In the film, there is nothing but agony as Jeet hears of the infamous train massacres, believing Aalia is lost.

The killing drove people to flee. Five million refugees passed into India and approximately the same number fled to Pakistan, with some twelve million left homeless. Alan Flack of the ICS wrote:

“Lots of people here are depressed and miserable about the transfer of power . . . The Punjab is an absolute inferno and is still going strong. Thousands have been murdered…”

Mountbatten and his wife were nevertheless energy personified: organizing guards of local politicians, deploying units to the worst affected areas, sending out medical units, and attaching security forces to trains and refugee convoys. Indeed, the crisis meant that Mountbatten ignored constitutional arrangements and issued instructions as a quasi-military commander.

British personnel had mixed feelings about the transition from India, summed up as bewilderment at the speed of the process, weariness, fatalism and professional indifference, a sense of abandonment of Indian personnel, but also affection, and pride. Like the Indians, all expressed a sense of shock at the scale and ferocity of the communal massacres taking place around them. Lt J. P. Cross, 1st/1st Gurkha Rifles wrote:

“Pressures of events obscured the heartbreak [but] it was a heartless and painful experience. On parting, tears were shed and the sorrow was genuine and hard to bear. [I was] indignant at the unseemly haste of having to meet an unrealistic political deadline. We were abandoning our men, we had broken trust and, by God, it hurt.”

One officer believed the breaking up of India ruined all that had been achieved and gave an equally emotional response: ‘to us it was the heartbreak of heartbreaks—it was something that one will never get over.”

But the sense of being broken up was worse for the Indians, and in Viceroy’s House, staff members go through the dilemma of choice. Some are clear. Others unsure. Field Marshal Claude Auchinleck, the Commander in Chief in India, captured the sentiment:

“Regiments like my own, half Hindu and half Moslem, were just torn in half – and they wept on each others’ shoulders when it happened … you felt your life’s work would be finished when what you had been working at all along was just torn in two pieces.”

Some scholars believe that Mountbatten recognised the inevitability of withdrawal and got the task finished as quickly as possible. Yet there is a widespread belief that he rushed the whole process, leaving too little time for negotiations which had the effect of increasing the urgency, desperation and violence. The view was widespread at the time. Sir George Cunningham, the Governor of the North West Frontier Province, wrote: ‘the opinion of most sensible people out here [is] that the trouble was enormously aggravated by the speed at which everything was done’. However, the Cabinet records and Mountbatten’s correspondence suggest the British felt responsible for the breakdown of law and order, but they no longer had the power to prevent it. They could only react to events.

Ed Brown, a soldier of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, captured another verdict: he felt that at the back of the ‘Jewel in the Crown’ there was:

“Squalor, hunger, filth, disease and beggary. Only when I came out of the army could I see what a terrible thing it was that a country had been allowed to exist like this. Such snobbery, so many riches, so much starvation.”

On the other hand, the British had refused to take a partisan position and remained even-handed to both sides (including preventing Jinnah taking half of India as he planned, and compelling the Princely States to choose one or other country rather than remain independent). They withdrew as they had pledged to do. They also refused to conduct a repressive campaign in 1947, as the French attempted to do in Indo-China and later in Algeria, which probably saved thousands of lives. Nevertheless, hundreds of thousands died in the violence that gave birth to India and Pakistan.

Viceroy’s House is available on Blu-ray and DVD from 7 August. For more the stories behind the making of the modern world, subscribe to All About History for as little as £26.