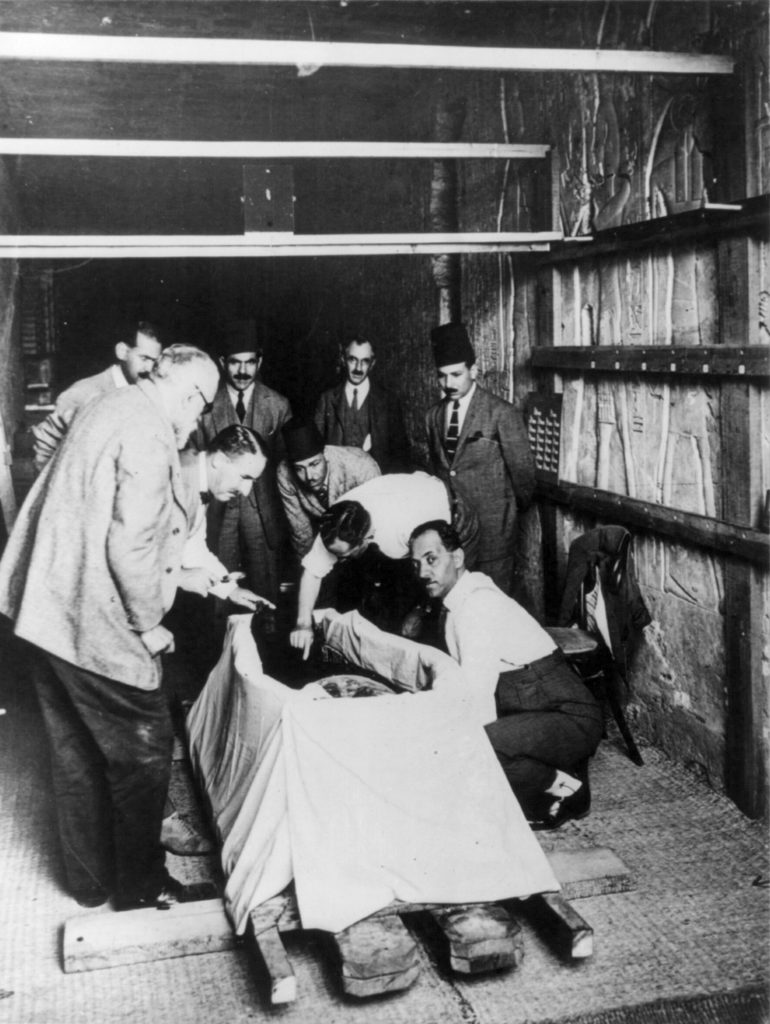

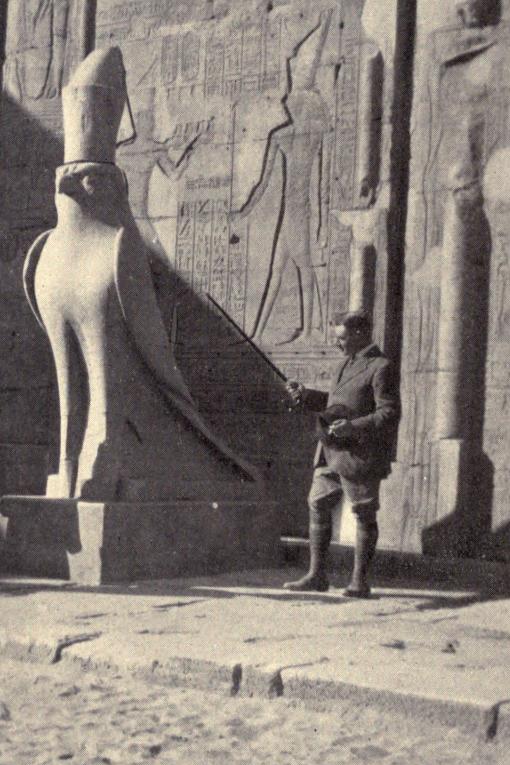

The last great discovery of the golden age of Egyptology – and the first in a new age of mass media – the unearthing of the tomb of the boy king was a sensation, talked about in the popular press and captured on flickering newsreels. The inner chamber was breached by archaeologist Howard Carter on 16 February 1923 and by April, Carter’s outlandish financier George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon (often referred to as ‘Lord Carnarvon’) was dead. The cause was gruesome and Carnarvon sliced open an infected mosquito bite while shaving, leading to blood poisoning and pneumonia.

It’s tempting to trace the ‘curse’ back to Daily Mail correspondent Arthur Weigall, who lashed out at Carnarvon giving exclusive access to the rival Times. In frustration at being unable to access the tomb, Weigall – as well as other newsmen who’d been cut off from the action – began to fill their stories with anything that came to hand, such as the death of Carnarvon’s canary which was grabbed by a cobra on the day the tomb was opened. It was an ill omen as Tutankhamun’s iconic gold and blue headdress is after all crowned by a spitting cobra, the symbol of the goddess Wadjet whose role was to protect of the Pharaohs.

A passionate (if controversial) Egyptologist who did much to popularise the subject back in Britain, Weigall was no friend to superstition but for lack of anything else to report he tried to have his cake and eat it. While professionalism – and sanity – prevented him from actually blaming ancient magical forces, he certainly massaged enough ambiguity into the matter for his readers to see exactly what they wanted to. In Tutankhamun and Other Essays (1923) he recalled being awed by the solemnity of the tomb being opened, and appalled by Carnarvon’s glib attitude issued what he unhelpfully described as a “prophetic utterance”:

“I turned to the man next to me, and said: ‘If he goes down [into the tomb] in that spirit, I give him six weeks to live.’”

A perfect example of Weigall’s knowing slight of hand and taste for theatrical high drama, in another essay he evokes a sense of melancholy at the mummified monarch’s exhumation by all but suggesting he’s one of the living dead:

The opening of this tomb still presented itself to my mind as the disturbing of a sleeping man […] It was as though he were somebody who had been left behind by mistake […] someone who was alone in an alien age, and who was being wakened to face thousands of staring eyes not filled with reverence but curiosity.

Rex Engelbach, the Chief Inspector of Antiquities for Upper Egypt, maintained that Weigall “disinterred the old story about bad luck coming from Egyptian tombs […] when my wife and I protested to Weigall, he said ‘But see how the public will lap it up.'” Even without Weigall’s early input, a rogue’s roster of spiritualists, gossips and hucksters were all too eager to see the hand of the otherworldly – and their enablers in the press were only too happy to follow-up their sober obituaries with titillating nonsense.

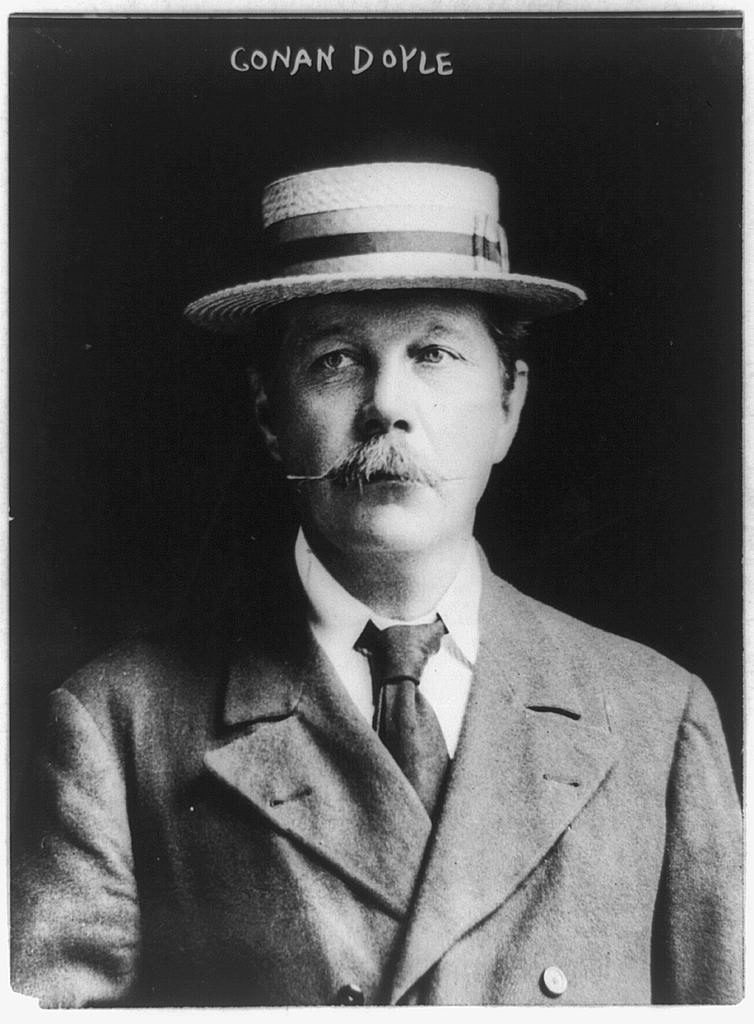

Sherlock Holmes creator and constant companion to all manner of tommyrot Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, speaking to newsmen in New York (reported in the Western Daily Press of 6 April), blamed “an evil elemental” and the long reach of the Press Association gleefully distributed his claims across the globe. The author had long since squandered any respectability through his increased obsession with the supernatural, his defence a series of hoax photos showing storybook fairies, and bitter public spats with his BFF-turned-arch-debunker Harry Houdini, but Conan Doyle’s outlandish utterances made for good copy.

With the conviction of the true believer, Conan Doyle explained that this elemental was “a built up, artificial thing, an imbued force, which may be brought into being by spirit means or by nature.”

He continued:

There was once a mummy in the British Museum […] which it was believed was guarded by one of those elementals, for everyone who came into contact with it came to grief. This was the mummy of a Queen, and even one of my dear friends, a journalist, who investigated the misfortunes that befell those who handled the mummy, was himself stricken with typhoid fever and died.

For their part The British Museum attempted a rebuttal quoted in the Hull Daily Mail (7 April):

None of the officials of the Egyptian department of the British Museum is aware of the existence of any such mummy. There is in the department, and has been for many years, the portion of a wooden mummy case about which various foolish stories have long been current, but to which the officials of the department attach no credence whatever.

By way of shoring up his authority on the matter noted that spiritualists were frequently in contact with spectres from Ancient Egypt and beyond, adding that “through my wife, who is a medium, I often get advice from one such [being] on spiritual matters. He lived 3,000 or 1,000 years ago in Arabia.”

As if the credulous Conan Doyle weren’t enough, Marie Corelli, wrote to the New York World to warn that:

I cannot but think some risks are run by breaking into the last resting place of a King of Egypt, whose tomb is specially and solemnly guarded, and robbing him of his possessions. According to a rare book I possess entitled The Egyptian History of the Pyramids, the most dire punishment follows and rash intruded into the sealed tomb. The book names ‘secret poisons enclosed in boxes in such wise that those who touch them shall not know how they come to suffer’. That is why I ask, Was it a mosquito bite that has so seriously infected Lord Carnarvon?

Corelli’s intervention carried as much weight as Conan Doyle’s. Although her name has been largely forgotten today, the novelist – a sort of softcore Stephanie Meyer – was a sensation who had counted amongst her fans Queen Victoria. That her “rare book” said nothing about Ancient Egyptian spiritual beliefs and everything about the superstitions of later Arabic chroniclers, was overlooked. Indeed, Conan Doyle’s “elemental” has more in common with the djinn of Arabic folklore than anything native to the time of the Pharaohs.

Soberly – and pointlessly given the plentiful spiritualists willing to churn out doom on demand – the Western Daily Press (6 April) observed:

Egyptologists not only discredit the idea of any supernatural factor in the death of Lord Carnarvon, but they regard the suggestion with impatience […] Sir Ernest A Wallis Budge, Keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities at the British Museum in an interview yesterday described such theories as “bunkum”.

Budge concluded archly in the same report that if curses were real “there would not be any archaeologists left today.”

Out of nowhere, claims of a foreboding warning inscription – “Death shall come on swift wings to him that toucheth the tomb of a Pharaoh” – adorning the burial chamber began to appear in the newspapers, a spontaneously manifesting smoking gun that Howard Carter insisted did not exist and no first hand accounts recall. That this inscription can’t be found at the site, then or now, has done nothing to dislodge it from the mythology of of ‘the Curse of the Pharaohs’.

Soon every death with even the thinnest connection to the dig (up to and including the sinking of the Titanic) was being blamed on the curse, while ignoring those at the heart of the excavation who lived to a ripe old age. Among the “victims’ was the tabloid-pleasing fate of Captain Richard Bethell and his father, Lord Westbury, as dreary case study in hysteria, rumour and outright fabrication as there ever was.

Bethell was Howard Carter’s secretary at the time of the dig and had even named his daughter Nefertari after Tutankhamen’s queen. He had been found dead in his bedroom at the Bath Club in Mayfair, suddenly and suspiciously, causing the likes of the Nottingham Evening Post (16 November 1929) to re-examine his recent history with their flimflam goggles on:

The suggestion that the Hon. Richard Bethell had come under the ‘curse’ was raised last year, when there was a series of mysterious fires at it home, where some of the priceless finds from Tutankhamen’s tomb were stored.

The same article admits that a footman – rather than a long dead king of Egypt – was charged with arson, but not every account was so honest. Three months later the orgy of mysticism continued as his father flung himself from the window of his seventh-floor flat, leaving a suicide note on black-edged which – as so enthusiastically reported by the usual suspects – began ominously: “I really cannot stand any more horrors.”

The newspapers referenced vague claims that “Lord Westbury was frequently heard to mutter ‘the curse of the pharaohs’, as though this preyed on his mind” and kept in his room a relic of dig conveniently inscribed with that familiar fabricated warning: “Death shall come on swift wings to him that toucheth the tomb of a Pharaoh.”

It would be stuff of gothic fiction, were it not for the accounts of the Coroner’s inquest. Placed back into context, Westbury’s suicide note paints an altogether less enigmatic portrait of a man whose ailing health had been met with deep despair at the death of his son. The nearest to full account of his suicide note, according to the Yorkshire Evening Post of 21 February 1930, reads:

“I really cannot stand any more horrors. I hardly see what good I am going to do here, so I am going to make my exit. Goodbye, and if you are right all will be well.” […] the rest of the letter, the Coroner said, was difficult to make out, but his lordship wrote something about Sister Catherine, a nurse, having a hundred pounds, and thanking his housekeeper for her overwhelming kindness. The letter ended up with: “I am off.”

Not the words of a man haunted by ancient curses, but a sick man haunted by grief as the Coroner concluded:

No doubt this poor Lord Westbury had been suffering very much and had great difficulty in sleeping. He also was old and depressed, and lost his son not very long ago. He appears to have kept his feelings very much to himself, as one would have expected.

Sobriety and sympathy, however, wasn’t on the menu. To add to the froth, Westbury’s hearse hit two young boys en route to the cemetary, killing one, which further fed the mania. Though how this blameless eight-year-old was somehow a fitting target for Tutankhamen’s revenge was never fully explained.

In January 1934 the curse claimed its patient zero as Daily Mail stringer Arthur Weigall’s passed away, with the press rushing to remind its readers that “the death of Mr Weigall recalls the story of a curse on the violators of the tomb of King Tutankhamen…” A bitter irony for the man whose desperation for good copy gave wings to the myth in the first place, but to see the sum total of the proud Egyptologist’s life reduced to a few paragraphs of breathless pulp fiction distressed his family then and galls the reader still.

Weigall was certainly known to Herbert Eustice Wicklock, curator of the Egyptology department of the Metropolitan Museum in New York and close friend of Howard Carter, who weeks after the death examined the ‘curse’ in detail. Winlock noted in the New York Times that of the 26 people present at the opening of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber, six had died within ten years while 20 were still alive. Of the 22 people present for the opening of his sarcophagus, only two had died, and of the 10 present at the unwrapping of the mummy… all we still alive.

Winlock scrupulously logged falsehoods and hearsay, debunking the more outrageous claims and issuing corrections to the newspapers. Ultimately it was all in vain. The stories kept coming and with them silver screen shockers like Boris Karloff’s The Mummy (1932) – inspired in no small part by the Curse – burying the details under the shifting sands of gothic romance, and ensuring fiction’s footfalls would be forever heard in truth’s shadow.

To give the final word to Howard Carter himself, writing in the preface to The Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen (1923):

The sentiment of the Egyptologist, however, is not one of fear but of respect and awe. It is entirely opposed to the foolish superstitions which are far too prevalent among emotional people in search of “psychic” excitement […] yet mischievous people have attributed many deaths, illnesses, and disasters to alleged mysterious and noxious influences in the tomb.

Unpardonable and mendacious statements of this nature have been published and repeated in various quarters with the sort of malicious satisfaction. It is indeed difficult to speak of this form of ‘ghostly’ calumny with calm. If it be not actually libellous it points in that spiteful direction, and all sane people should dismiss such inventions with contempt.

For ancient history, pick up the All About History Book of Ancient Egypt or subscribe to All About History and save 25% off the cover price.

Sources:

- The Mummy’s Curse: The True History of a Dark Fantasy by Roger Luckhurst

- A Passion for Egypt: Arthur Weigall, Tutankhamun and the ‘Curse of the Pharaohs’ by Julie Hankey

- Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun by TGH. James