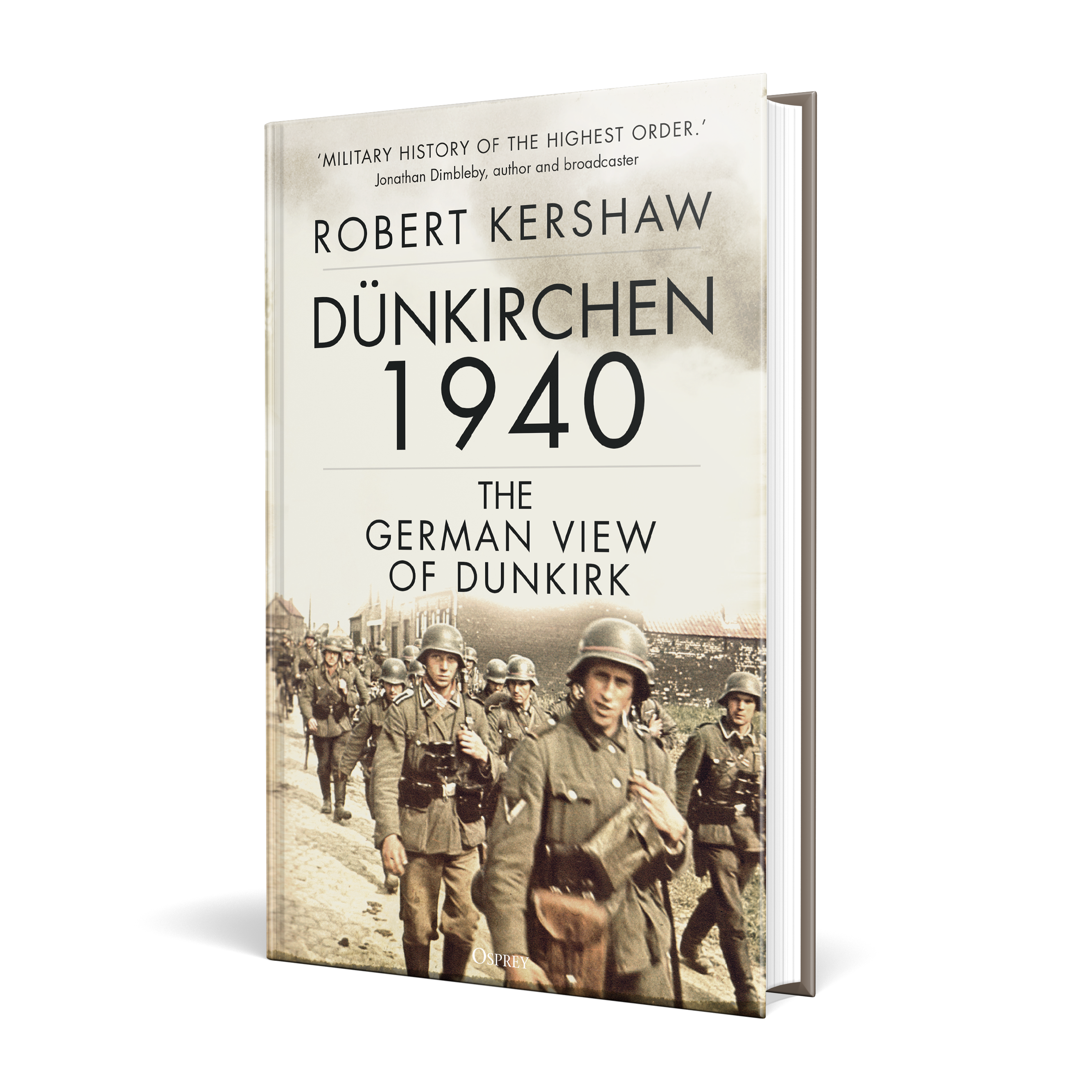

For the British, Dunkirk was one of the defining battles of the Second World War, the armada of ‘little boats’ coming to symbolize courage and defiance as they rescued the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). But how did the Germans view the battle? Historian Robert Kershaw’s new book provides a thorough, account of this question.

This month History of War readers can WIN one of three copies of Dünkirchen 1940 – see below for more details.

As the author of this intriguing book, Robert Kershaw has ‘form’, having previously written It Never Snows in September and War Without Garlands, both accounts of major Second World War battles from a German perspective, the former on Operation Market Garden and the latter the invasion of the Soviet Union. This time round Kershaw has chosen to explore Dunkirk, a battle totally embedded in Britain’s Second World War psyche and immortalized in countless films and books ever since – but always from the British standpoint – which makes Dünkirchen 1940 a daring choice of topic, and one Kershaw pulls off handsomely.

As usual Kershaw – an ex-British Army paratrooper himself – has researched his subject thoroughly and focused on first-hand accounts by ordinary German soldiers – the landsers – although he admits the difficulty of the task given so few of the landsers involved in the battle survived the War, most being killed over the next four years in Russia. Add to this the German forces involved never numbered more than ten divisions, and a relative paucity of accounts is only to be expected, but despite this Kershaw has been able to unearth enough material to really give the reader an excellent feel for the reality of the fighting. This is especially true of the last quarter or so of the book which tells the story of the battle during its final few, bitter days.

The book begins by placing Dunkirk in the context of Nazi Germany’s attack on the West, and Kershaw begins as he means to go on by focusing on the campaign from the German side with Hitler’s gamble to back Erich von Manstein’s radical Sichelschnitt (sickle-cut) plan and invade France through the thought-to-be impassable Ardennes. With Schnelle Heinz (Fast Heinz) Guderian’s panzers then racing to the sea, splitting the Allied armies in two and trapping the best of the French and the entire BEF in the north of France and Belgium. Kershaw describes what the German soldiery thought of their opponents as they battled forward, with the French ranging from anywhere between excellent to “an army without spirit and drive”, the British as “courageous and disciplined” and the Belgians proving tough nuts to crack.

For the Germans the headlong advance was unprecedented, and the author sharply contrasts the success of the Wehrmacht’s 1940 offensive with the dismal failure of the Imperial German Army’s 1914 invasion of France. Although the linkage between the military efforts of fathers and sons was often tragic as Helmut Neelsen described when he and his comrades crossed the River Lys under heavy fire; “Our company commander…was severely wounded…He was wounded in the same place where, over 20 years ago his father – who also gave his life for Germany – lies. Shortly after he died himself…”.

Given the book is from the German viewpoint there is relatively little of the book dedicated to the details of the evacuation and the ‘little boats’, and instead a big focus on the Wehrmacht’s attempts to pierce the defensive rearguard – both British and French– and this is entirely appropriate. The narrative also explores aspects of the battle that have often been overlooked previously, including the shock felt by German troops in being the target of RAF ground attack, and the nature of the terrain over which the Germans were forced to attack to try and capture Dunkirk.

However, probably the most interesting point the book makes is to question the narrative that it was Hitler’s famous ‘panzer stop’ order – supposedly given against his generals’ advice – that allowed the BEF to escape and robbed Nazi Germany of a decisive victory. Kershaw presents a very good case that the order was only temporary and was strongly approved of by his senior commanders who were desperately worried by their foot slogging infantry’s inability to keep up with the blitzkrieg of the new panzer divisions. In this he joins the growing voice among modern historians challenging the postwar orthodoxy – propagated by the Wehrmacht’s senior officers – that Germany’s defeat was entirely down to Hitler’s mistakes rather than their own.

Kershaw also, rather bravely, explains to his British readers that Dunkirk wasn’t as important to the Germans as defeating France – their Erzfeind (archenemy), and that, in fact, the Germans saw Dunkirk as secondary compared to a renewed push to take Paris.