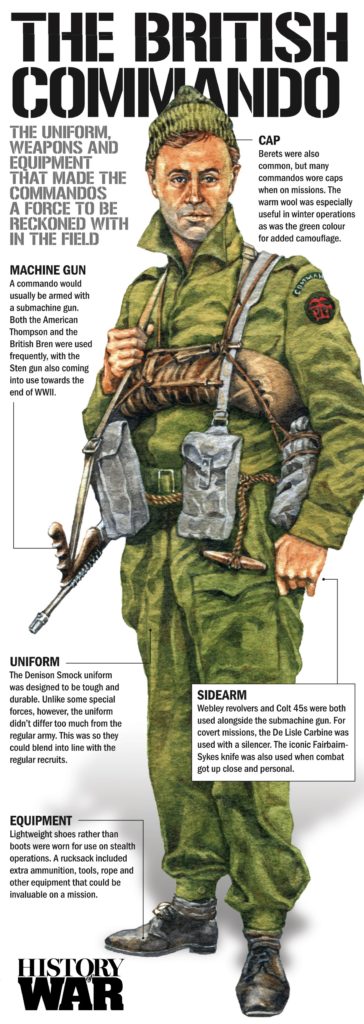

It’s 1940 and Britain has just weathered the first waves of the blitz. After the evacuation of Dunkirk, Churchill and his war cabinet have some respite to decide what is the best way to retaliate against the Third Reich. They make the decision to form an elite force that will be better than the best the Wehrmacht has to offer. The result is the creation of the British Commando regiment.

The commandos would become an instrumental part of the Allied fighting force during the war. Men were recruited from all over Britain to take part in what was simply called ‘service of a hazardous nature’. From D-Day to the Far East, the specialised units would become the scourge of the Axis forces. Despite initially having little training, these shock troops proved so effective that Hitler authorised the ‘Kommandobefehl’ (Commando Order), stating that German soldiers should eliminate any Allied special forces soldier on sight. This went directly against the original Geneva Convention and demonstrated just how these soldiers got under the skin of the Nazi hierarchy. Their job done, the British Commandos were disbanded after the war, but their role and skill set has lived on in the Royal Marines.

1. St Nazaire Raid (28 March 1942)

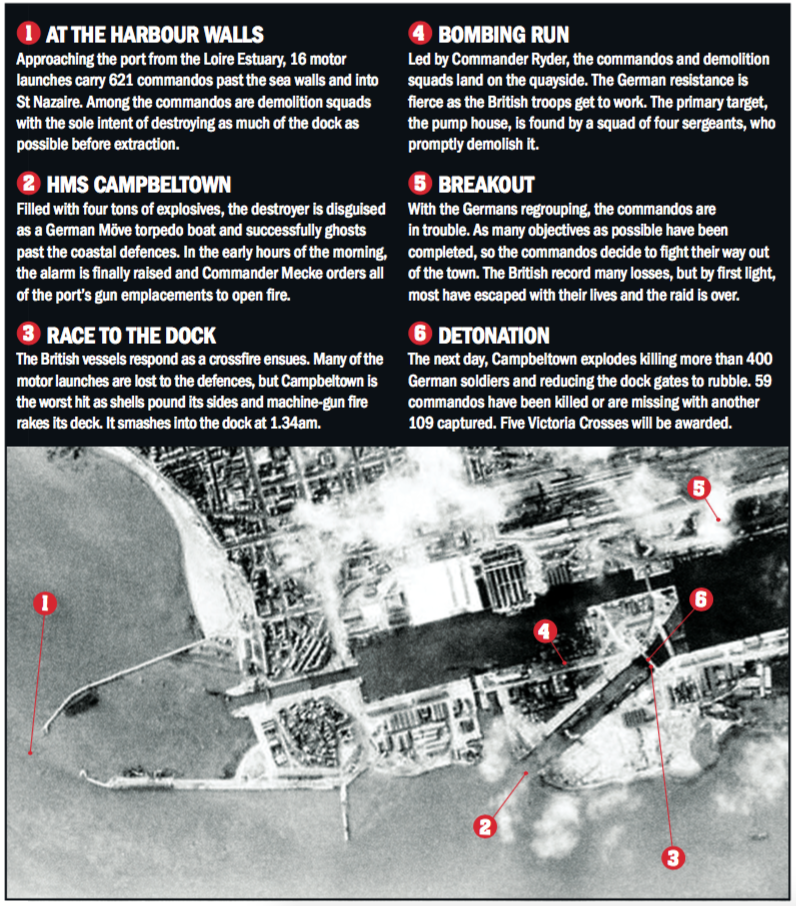

One of the finest acts of courage in the whole of World War II, the raid on St Nazaire was a true gamble. The best way to hurt the Kriegsmarine was to strike its dockyards, so the port became a key target for the British in what would be known as Operation Chariot.

The tricky part of the attack was reaching the harbour, as it was not exposed to open sea, so the commandos would have to navigate an eight-kilometre (five-mile) estuary as well as avoid a multitude of German anti-aircraft flak guns. Even worse, they could not use the tactic of blanket bombing due to the high number of civilians in the surrounding area, and naval support was tricky due to the narrow estuary.

Under the command of Lord Louis Mountbatten, the decision was taken to pack the destroyer HMS Campbeltown full of explosives and ram its full bulk into the dock while men from the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 9th and 12th Commando rode alongside the vessel in small motor launches.

Despite having the cover of night and taking a variety of precautionary measures, the Germans were alerted, meaning only a few of the motor launches made it to the docks. Once ashore, the commandos and demolition squads rushed into the submarine pens to arm explosives. The main objectives were:

- Completely destroy the two caissons of the Normandie Dockyard.

- Demolish as many of the dockyard facilities as possible.

- Break down the lock gates.

“After Campbeltown exploded, the St Nazaire dry dock was rendered inoperable for the rest of the war,” explains Dr Peter Johnston from the National Army Museum. “This severely limited the ability of the German surface fleet to operate in the Atlantic and threaten the convoys on which Britain depended. Because of the raid, the German Navy never sent the Tirpitz into the Atlantic for fear that, if it needed repairs, it would have to return to German waters via the English Channel where the Royal Navy Home Fleet could threaten it. Instead, the Tirpitz remained in the Norwegian waters until the RAF destroyed it on 12 November 1944.

“The raid also accelerated German plans for the Atlantic Wall. Ports, in particular, were increasingly fortified to prevent a repeat, and by June 1942 the Germans began using concrete to fortify gun emplacements and bunkers. While this diverted resources away from other German theatres of war, it would also make any future landing in Europe more difficult for the Allies.”

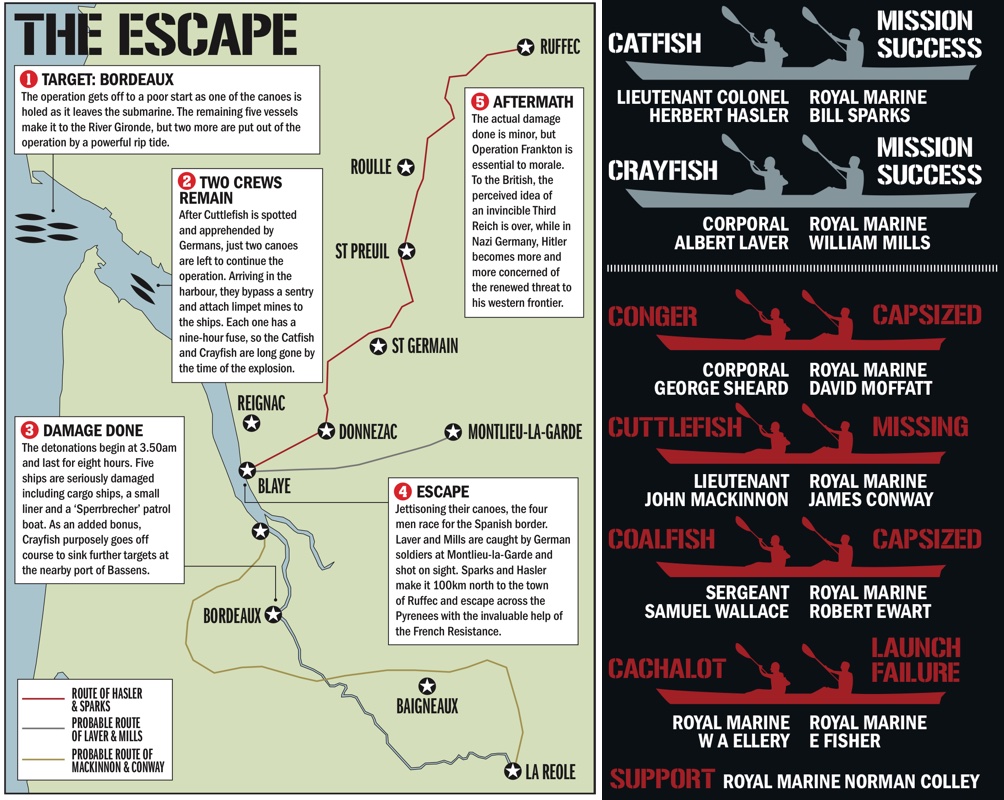

2. The Cockleshell Heroes (7-12 December 1942)

One of the most unusual missions of the war, Operation Frankton is remembered for helping maintain the Allied blockade between Japan and Germany. The idea of using canoes for infiltration behind enemy lines came from the British witnessing the success of the Italian canoes in December 1941, which did major damage to the battleships Elizabeth and Valiant. By 1942, the Allied blockade on Germany was becoming less and less effective, especially at the port of Bordeaux. After deliberating the more conventional forms of assault, it was decided that canoes would be the method of attack.

Split into two divisions, the objective was to destroy German ships in the harbour. After a series of faults, only the canoes Catfish and Crayfish managed to make it to Bordeaux. While taking cover in some vegetation, the four men were discovered but managed to convince the civilians that remaining silent would be the best course of action. The two canoes pressed on for days and eventually made it to their target on the night of 10 December. Making their way into the docks, the fuses on the limpets were set.

On the next night, more mines were attached to cargo ships and patrol boats as five ships and the harbour itself were badly damaged. At one point, Catfish was spotted by a sentry, but its camouflage saved the day as the soldier turned away again. Their work done, the canoes were scuttled and the crew made a hasty escape to the safety of the Spanish border. The success of Operation Frankton is credited with helping shorten the war.

Dr Johnston from the National Army Museum commented: “The long-term effects of the raid were not as significant as those of St Nazaire – but they did of course have an affect on the German war machine.

“However, nothing should detract from the bravery of the men who carried it out. A small team that was well led, well trained and dedicated to success, inflicted damage far outweighing their small capacity. The Germans became increasingly defensive and committed more resources to guarding ships in harbour – men and material that could have been deployed elsewhere.”

3. The Bruneval Raid (27 February 1942)

In previous attacks on this radar station in northern France, Flak gun emplacements had nullified the impact of bombing squadrons. The Germans boasted highly advanced radar systems that repeatedly helped knock the RAF out of the sky. As a result, commandos from C Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Airborne Division were sent on a mission that would be known as Operation Biting, or simply the Bruneval Raid. Led by Major John Frost, C Company was tasked with the destruction of a house on the cliffs of Bruneval. Seemingly inconspicuous, it was actually being used as an important radio and signalling location for the Germans that acted as an early warning system of approaching Allied ships or planes.

To avoid the machine-gun posts and barbed-wire fences, C Company was dropped a fair distance behind the house, before advancing closer. Using their expert infiltration skills, the commandos clinically took care of business as they killed every occupant of the house.

The next part of the operation was to destroy the radio; as this was being done, German fire came in from a neighbouring farmhouse. 12 of the company dealt with the attackers, and after the dismantling of the machinery was complete, it was time for extraction. At first, no contact could be made with the Royal Navy as the relief vessels had been nearly spotted by Kriegsmarine destroyers. Finally, the boats arrived under a hail of German machine-gun fire and the commandos escaped to safety, their mission complete. A day later, a lone Hurricane flew over the area undetected – Operation Biting had been a success.

“In 1941, British reconnaissance aircraft had photographed the Würzburg radar installations, but experts in Britain were not sure what they were and how they functioned,” explainedDr Johnston from the National Army Museum. “Bomber Command was suffering heavy casualties in air raids over occupied Europe, and it was essential to understand how German defences worked so that they could be negated.

“The capture of the radar enabled British scientists to analyse it and better understand it. It was this examination that confirmed to British scientists their suspicion that the Germans had developed radar that was resistant to the jamming methods that the British were currently using. A new solution was needed, and so the British put the Window countermeasure into use. The results were spectacular, and Germans were forced to develop new defensive strategies and technology.”

4. Operation Colossus (14 February 1941)

In February 1941, 35 men from No. 2 Commando were dropped into the heart of Axis Italy. The mission was one of sabotage, and the objective was to destroy a railway viaduct in the Apennine Mountains, north of Naples. The Tragino Aqueduct was the water supply for three Italian ports, and the operation was led by Major T Pritchard, who trained his X troop for Colossus from nearby Malta. Along with the main raid, a diversionary attack was carried out in Foggia to draw the Italians away. Back in Tragino, the commandos had dropped in and the explosives were armed and ready to go.

The huge explosion successfully eliminated the aqueduct, but the raid soon got difficult as the extraction of the men became tricky. The original plan was to evacuate the commandos via submarine, 60 miles away, but this idea had to be abandoned when the extraction site was discovered by the Italians. There were no plans for an alternate method of withdrawal, so the men were forced to split into four groups and escape across the countryside on foot.

Slowed down by the need to stay hidden in farms and small villages, they were soon all captured. The Italian spy and interpreter Fortunate Picchi, who was working for the British, was tortured and executed, while the others were sent to POW camps.

The mission was a success, but the aqueduct was soon repaired, nullifying the damage of the explosion and the mission. However, the operation proved that commandos could (andwould) cause havoc behind enemy lines for the remainder of the war.

5. Operation Claymore (3 March 1941)

The Lofoten Islands were home to several German glycerine factories that supported the manufacturing of weapons for the Third Reich. To put an end to this armament production, 500 men from No. 3 and No. 4 Commando were sent to destroy the plants. After a three-day journey where seasickness ravaged the men, the British arrived on 4 March. Lowered down onto thick ice, the commandos stormed into the German compounds, completely surprising the Wehrmacht soldiers stationed there. Advancing through the chilly environment, the commandos swiftly rounded up the defenders and set charges on factories, military buildings and ships. 225 Germans were taken prisoner with the loss of no commandos. It has been reported that the local Norwegians were so happy at the sight of Allied soldiers that they offered ersatz coffee to them all.

The mission was such a success that the British saw the event as an ideal opportunity to poke fun at the Nazis. Lieutenant RL Wills sent a mocking telegram to ‘A. Hitler’ in Berlin saying: “You said in your last speech German troops would meet the British wherever they landed. Where are your troops?” If the operation couldn’t have gone well enough, as an added bonus, the commandos came across some spare rotors for a German Enigma machine, which were sent straight to Bletchley Park for study by Alan Turing and his team.

Dr Peter Johnston from the National Army Museum commented: “Commando raids in Norway had a significant effect on the Third Reich’s war machine, and had important knock-on effects with other theatres of war. They provided an opportunity to gather intelligence through captured prisoners and restore British morale. The forays helped capture a set of rotor wheels for an Enigma machine and its codebooks. This meant that the British could read German naval codes at Bletchley Park, providing the crucial intelligence that helped British convoys avoid German U-boats.

“Similarly, Operation Gunnerside in 1943, which was run by the British using Norwegian commandos, saw the targeting of the Norwegian heavy water production facilities to slow German development of an atomic bomb. These raids also helped stretch German military resources from other theatres. After Operation Archery, the Germans sent 30,000 troops to Norway to upgrade coastal and inland defences.”

6. Operation Dryad (2-3 September 1942)

The closest Hitler ever came to a conquest of Britain was the Channel Islands. The Casquets off Alderney were home to a German naval signalling station and also some secret codebooks. An attack on the complex had been attempted many times prior to September 1942, and this time a team from No. 62 Commando was assigned to the task. The lighthouse was protected by razor-sharp rocks that were a magnet for shipwrecks, but the commandos managed to scramble on land after disembarking a torpedo boat 800 yards from the shore.

With the noise from the waves covering their movements, the 12 men scaled the cliffs up to the walls of the compound. The seven German defenders were armed with Steyr rifles and grenades, so stealth was key. With a mixture of tactical espionage and German slackness (the defenders were either asleep or not willing to resist), the lighthouse was captured without a shot being fired. However, the raid was not over.

Upon leaving the rock, one of the commandos, Adam Orr, jumped aboard the escape boat, knife in hand, and in the choppy water stumbled into one of his fellow marines, Peter Kemp, stabbing him in the thigh. Worse still, another one of the group, Geoff Appleyard, broke the tarsal bone in his ankle when he slipped down from a rock. The mission complete and the injured safely aboard, the prisoners were interrogated upon the return to the mainland and provided the British with valuable information on German positions, movements and manpower.

7. Assault on Walcheren (1-8 November 1944)

Antwerp was a major target for the Allies. Home to one of the biggest ports in Europe, its occupation was key to increasing the pressure on the shrinking Third Reich. However, the holding of the port was useless without access to the mouth of the River Scheldt. Walcheren was an island that was heavily fortified by the Germans with bunkers and coastal guns, and it prevented mines being cleared to allow ships in to the river estuary.

The island would be attacked under Operation Infatuate with a pincer movement from two directions. From the south, the commandos of 4 Special Service Brigade would attempt an amphibious landing while being supported by Canadian troops from the north. A gap in the dyke had been formed by earlier RAF bombing, and the Royal Navy drew German fire away from the infantry. The tower at Westkapelle was the first to fall, followed by a radar station.

The next objective was the batteries, which were eventually taken after many commando casualties. With only one battery left to take, the German commander negotiated the surrender of his remaining 4,000 troops in the area. The mission was complete, but before the day was over, disaster struck as one of the amphibious landing vehicles ran into a mine. 18 men were killed with a further nine wounded.

8. The Måløy Raid (27 December 1941)

By Christmas 1941, the Wehrmacht had occupied Norway for more than 18 months. In this time, the Germans had extracted copious amounts of ore to fuel their armed forces. To strike back, the Allies launched Operation Archery on the islands of Vågsøy and Måløy alongside Operation Anklet on the nearby Lofoten Islands.

The raiding force was a hybrid of three commando units (No. 2, No. 3 and No. 4) and a Royal Norwegian Army Group totalling 525 men. There were no Axis warships to combat, but the Wehrmacht 181st Division along with substantial fortifications and air support would be a tough nut to crack. Finishing up their Christmas dinner on HMS Kenya, the troops were deployed. The first move was taken by the Royal Navy, which opened fire on the coastal defences, followed by the RAF, which provoked the Luftwaffe into action while also creating a smoke screen for the commandos to advance under. Initially surprised, the Germans fought back with force but their resistance was stifled by the British floating reserve that blocked reinforcements coming from the north of Vågsøy. The commandos escaped having killed 150 Germans and taken 98 prisoner. They were also joined by 71 Norwegians who were fleeing their occupied country.

The results were not limited to land, as nine ships were sunk and four aircraft downed. The Måløy Raid was a successful precursor to Operation Claymore.

For more special forces history from some of the world’s best military historians, subscribe to History of War for as little as £26.