Just after midnight on 8th December, 1941, Japanese forces landed on a beach near Kota Bharu, on the north-eastern coast of what was then British Malaya (now peninsula Malaysia). Conventional wisdom at the time regarded Japanese weaponry as inferior and Malaya’s virgin jungles as impenetrable. The Japanese, it was thought, could not win. Even if they landed in Malaya there was always the backstop of ‘Fortress Singapore’, the island on the southern tip of British Malaya.

“Singapore shall never be taken while Britain lives – that is what London is saying this morning…”

The Straits Times of Singapore, 15 December 1941

On the battlefield itself, the swiftness and efficiency of Japan’s takeover was breathtaking.

- 19 December 1941: Penang falls

- 11 January 1942: Kuala Lumpur is occupied

- 15 February 1942: British forces capitulate in Singapore.

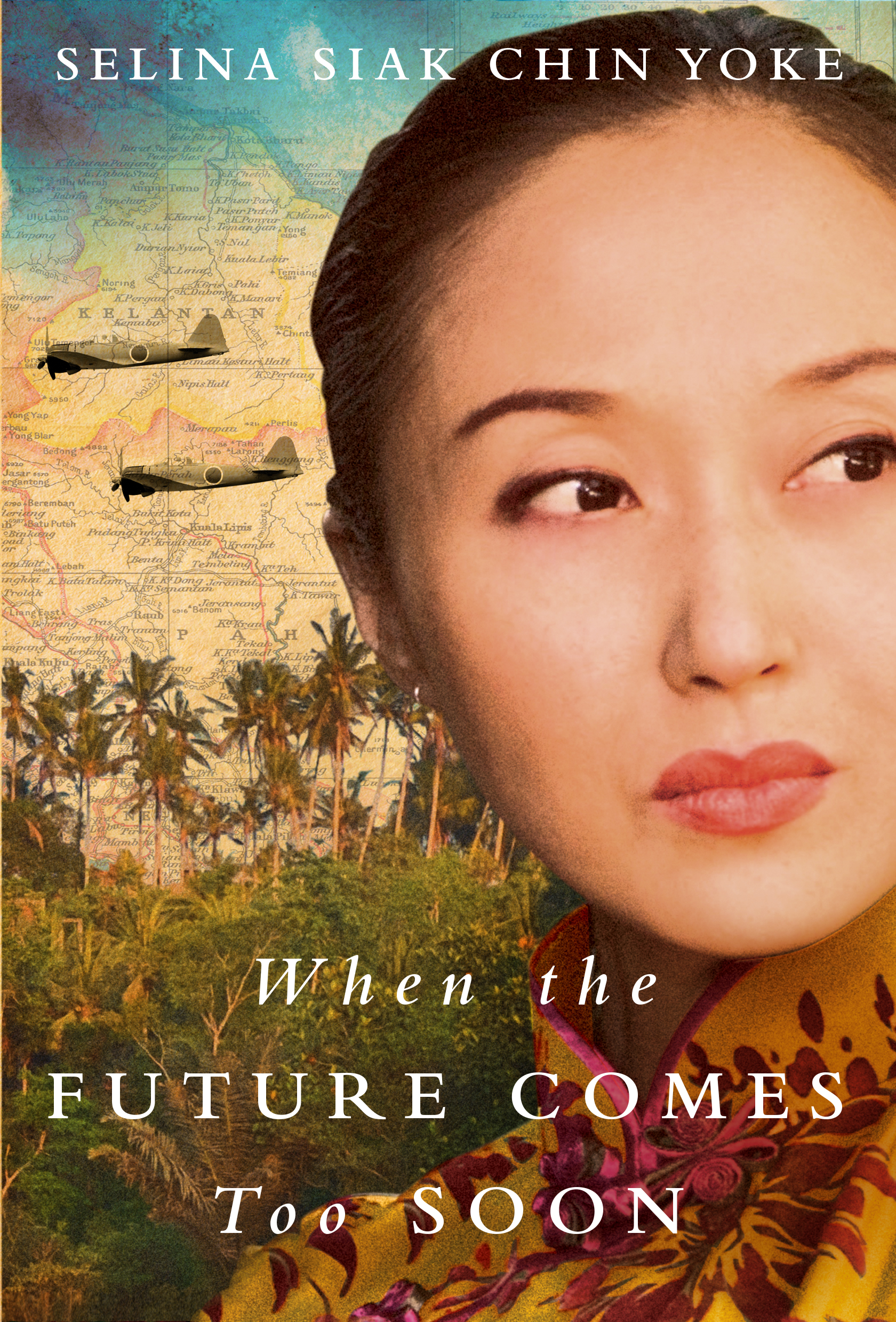

Thus began the Japanese occupation. It would last 3½ years. This is the climate in which my second novel, When the Future Comes Too Soon, is set.

The suffering of the majority of Malaysians in that period has been largely forgotten. Fictional stories set in WWII Malaya have often been from a colonial perspective, involving the torture of prisoners of war, for example, or the small band of white soldiers that was belatedly parachuted in to bolster the local resistance, the so-called Force 136. While not denying their bravery, in reality, the vast majority of the population, who have been sidelined in the overall narrative, had more pressing issues of survival. It is symptomatic that after Britain had re-occupied Malaya, the war reparations it sought from Japan were in respect of British property and commercial interests. I became indignant when I read this at Malaysia’s National Archives in Kuala Lumpur.

I was increasingly aware that there was another set of stories – the ones I grew up listening to – about what the Japanese occupation was really like. These stories were unwritten and unpublished, and had only been passed down verbally. I knew that if I could write such a story, it would shine a new light on the stresses and struggles experienced by many Malayan families during WWII.

But anecdotes are one thing: a historical novel requires accuracy. For the brand of historical fiction I write, where I aim to immerse the reader in the era, I needed a huge amount of detail, and all of it had to be accurate. I used a mix of sources, beginning with archived newspapers.

From the outset, I was shocked by the things I learnt. No one had told me about the disgraceful way in which the colonial government abandoned Malaya. This is such a far cry from the British fair-mindedness I know that it was hard to believe. Archived papers, though, were telling. Every day in December 1941 brought news of yet another ‘strategic retreat’ – and these took place all the way down the western coast of peninsula Malaya. Following the ‘evacuation’ of European civilians from Penang, the Straits Times on 23 December 1941 said:

“The Governor (of Singapore) referred to the evacuation of European civilians from Penang. He said that this was done without his knowledge or that of the Colonial Secretary. He gave an assurance that if it became necessary in the future to yield any district to the enemy, a sufficient number of European Government officers would stay with the people to look after their needs so far as they could, even though they might fall into enemy hands.”

In the event they left: officers, medical personnel (with equipment), civilians. A few brave souls wanted to stay but were ordered to go.

The story in When the Future Comes Too Soon takes places in Ipoh, my hometown. I therefore revisited the places I had grown up seeing, such as the large field in the centre of town – the Ipoh Padang. This former cricket pitch was where the Japanese army sent Chinese men to stand under the midday sun. In the mornings, the same field was used for the exercise drills which the Japanese – who wanted to be called Nipponese, not Japanese – were keen on, exercises known as Radio Taiso. To get a better idea of what Radio Taiso was, I relied on good old Google. You can even find videos of Radio Taiso on youtube!

One of my granduncles, Chin Kee Onn, kept handwritten notes throughout the Japanese occupation. It’s fortunate that the Nipponese never found them! After the war he turned his notes into a non-fiction book called Malaya Upside Down, which became a Malaysian classic. I used a lot of details from his book.

I also interviewed people who actually lived through the occupation as adults. I could still see the fear in their faces 70 years later. Everyone mentioned that there had been no rice – which to us is unimaginable – especially in a country as fertile as Malaysia.

At the end of the day, research only gets you to a certain point. I still had to imagine the details of every scene for myself: no one else could do that for me. All of the things which my characters go through in the novel – from the protagonist changing her currency into Nipponese notes to her husband having to join a Jikeidan, or neighbourhood watch group – all of these actually happened. Real events anchor my novel. The only poetic licence I took was in changing their chronology for dramatic effect.

The result is an emotional story about an era most of us today would find hard to imagine. It is no exaggeration to say that the events recounted in When the Future Comes Too Soon changed the face of Malaysia. I very much hope I’ve done justice to the memories of those who shared their stories with me. For others I hope that my novel brings colonial Malaya: the sights and sounds, also the plethora of attitudes and prejudices.

The majority of Malayans could not flee, could not live out the war in Australia. I would love for their stories not to be relegated to the footnotes of history.

When the Future Comes Too Soon by Selina Siak Chin Yoke is out now. For more on the Pacific front of World War II, subscribe to History of War for as little as £26.