The evacuation of Allied forces from the beaches of Dunkirk is one of the most dramatic and pivotal events of WWII. Between 27 May-4 June 1940 over 338,000 British, French, Canadian and Belgian troops amongst others were successfully evacuated against huge odds in over 900 vessels, the majority of them privately owned. After the horror of the Battle of France the evacuation became instantly iconic and symbolised Britain’s resolve to continue fighting Nazi Germany no matter what the cost.

This determination ultimately changed the course of history and along with the subsequent Battle of Britain immediately afterwards the United Kingdom was able to survive long enough for the USA and the Soviet Union to join the war effort the following year. Four years later Britain acted as the springboard for the western invasion of Europe and victory was finally achieved in 1945.

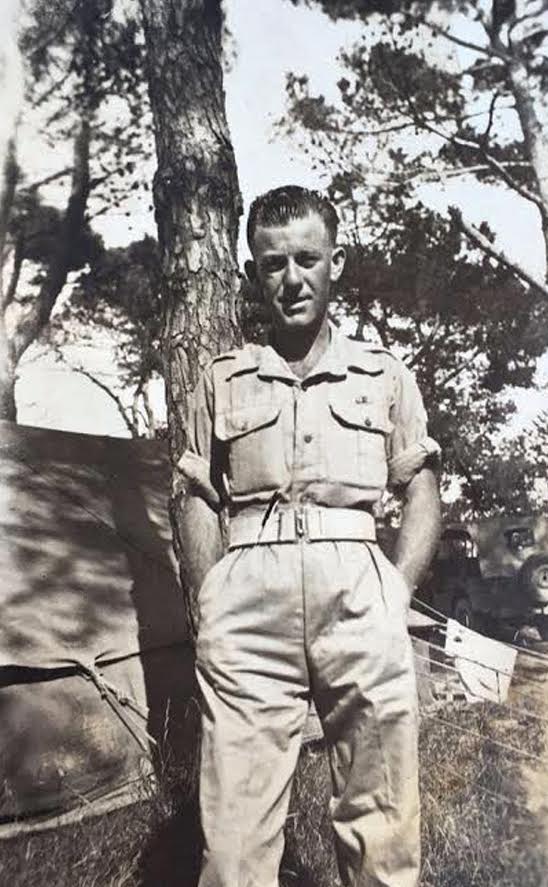

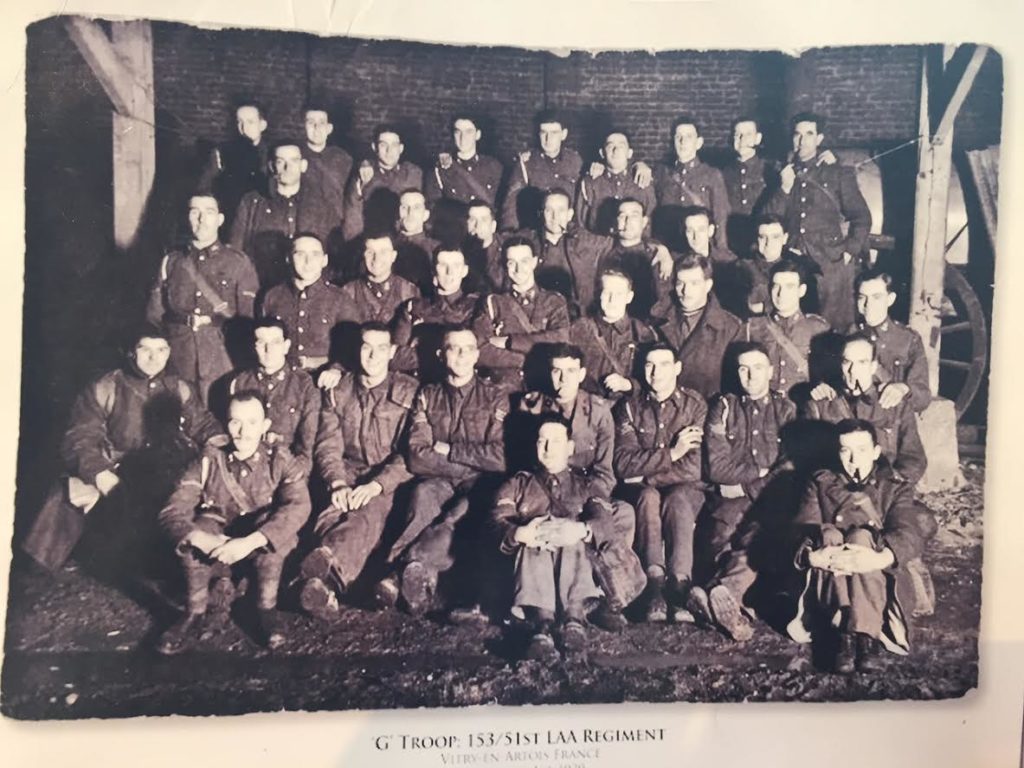

One of the evacuated soldiers from Dunkirk was Gunner Garth Wright, a 20-year old British artilleryman and despatch rider from 153 Battery, 51st Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery. Born in 1919 and now aged 97 Wright is a living symbol of the “Dunkirk spirit” and with the high-profile release of the Christopher Nolan’s motion picture Dunkirk, his dramatic story has now come centre stage. 77 years after his brutal experiences in France Wright spoke to History of War about his moving and remarkable survival.

Training and Arrival in France

When did you join the British army?

I joined around June-July 1939. When I joined up there were five of us originally. There was myself, Ken Stephens, Roger Palmer (we called him Reg), Harry Anderson and Peter Dodd. We were brothers-in-arms, we were very close friends before the war and we went across as one when war broke out.

I’ve read that your training was a little rudimentary?

It was indeed. There were Bofors 40mm anti-aircraft guns, pulled by a tractor which I drove. I was a despatch driver to start with and I finished up as a tractor driver. Our basic training consisted of going up to Plasterdown on a Sunday and we’d have perhaps one gun up there. Somebody would run around amongst the gorse bushes and suddenly pop up with his hat in the air and the sergeant would give the bearings of the target: that was out basic training. That was virtually the only training we had before we went into serious action in 1940. It was very, very basic indeed.

When war was declared, where were you and how long was it before you were deported to France?

It was a Sunday morning when war was declared. We were having a church service up at Tavistock Guildhall with the local Salvation army band and when 11 o’clock came they said that there would be an important announcement. It was old (Neville) Chamberlin: he came on the wireless and said that they had given an ultimatum to Mr Hitler that if he didn’t pull out of Poland then a state of war would be declared. He came on the radio and said no such assurance had been given by Mr Hitler. As a result we are indeed at war with Germany. That was 11 o’clock on 3 September.

Some of the boys cheered and at the time I wondered what they were cheering at because I knew then that it wasn’t going to be a short affair. We were in for a pretty long haul which indeed it was.

We were then on our bikes. We set off for Avonmouth on the Monday morning and we left a lot of the young lads and the older boys behind. We just had a skeleton battery made up of people of the sort of age that would be expected to go to the front. We went up to Thursley camp to pick up some more vehicles and things like that and a couple more guns and also some reservists that had already done their 21 years in India and came out. They joined us: about a third of out battery was made up of these old sweats that had done their time. We then went from Avonmouth down over to Saint Nazaire and landed there and unloaded. We were greeted by a meal from the French boys, they were dishing out bowls of soup. I questioned the soup and said, “Is this horse?” They almost gave me a wallop with the ladle so I thought I better keep my mouth shut and eat up!

What was your job while you were based in northern France?

We made our way up to Seclin, which is an airport by Lille. Our first job was in defence of the airport, which was the main airport for Lille and also one of the forward aerodromes. We set up there until the balloon went up in 1940.

I read that you were digging trenches on First World War battlefields. Can you describe what that was like?

When we landed in Saint Nazaire we moved into Merville and wherever we went we dug in and used our guns: that was the basic job to do. I was digging out a gun pit and every shovel full of earth that came up had a momento of the terrible battle from WWI: cap, badges, buttons and little bits of bone. I wish I had kept some of it but there was so much of it at the time and in any case I couldn’t of got it back home after Dunkirk. What a terrible war that must have been. I think that Merville was one of the spots that even in WWI it was one of the worst battles. Farmers were going around digging up and were taking out shells and unexploded stuff, just parking it beside the field. I could see massive things such as artillery pieces. It was everywhere.

The Blitzkrieg comes to France

What was it like to be on the receiving end of blitzkrieg when the Germans launched their campaign in 1940? Did the speed alarm you?

The Germans set off with their blitzkrieg lightning strike, and it was indeed! It was really frightening. It was men against boys really, they’d had armoured experiences on other fields of war in Poland and Czechoslovakia. They went through us like a dose of salt.

Conditions were made worse by Me 109s, which were coming over strafing along with Stukas dive-bombing. A lot of people poo-pooed the Stuka but by God it was an effective plane. It was sure to hit the target: you just aimed the plane at the target and the only target the gunner on the ground had was a little thin line coming down. You could see the bomb leave the plane and you knew damn well that it was going to land directly on your gun. What do you do? Scarper, or do you stick it out? Well of course it was pretty frightening.

Were you aware of their success in places like Poland and Czechoslovakia?

We weren’t prepared for that sort of warfare and the French in particular were still horse-drawn. We were not much in advance of them at all. It was a Blitzkrieg all right.

What are your memories of encountering refugees on the road to Dunkirk?

The refugees choked the roads and to make matters worse the Germans came down with their Me109s strafing the roads. The refugees, poor devils, were killed or choking the roads: you couldn’t move. If we did try any manoeuvre or try to put up a fight we couldn’t have done it and the Germans had no interest in life, they just rolled right through them.

Can you tell me about the time you gathered supplies from an abandoned RAF airfield?

We were guarding the airfield and word went around that the RAF had pulled out and took their planes, Spitfires and Hurricanes, back to England and thank the lord they did because they saved us during the Blitz. Word went round that all their NAAFI stuff was up there for the taking so I took my 30 underweight truck, went up to the NAAFI and sure enough there were bottles of whisky, fags and lots of goodies so I loaded that up.

I took it back to my billet but on the way out the aerodrome the CO Major Stephens, who liked a little tipple himself, was driving in. By the time I got back to the billet he was there and said, “I suppose you know what the penalty for looting in wartime is?” I said, “That’s not looting sir, it’s salvaged” He said, “Aye, but in my book that’s looting so get in this hut and I’ll get the firing squad for you.”

So he locked me in and I was waiting. The CO was always mad drunk. He was running up and down the day before with his Webley revolver shooting at planes a mile high. He was tiddly as a goat but he was going to shoot me for looting! I was biting my nails and the captain Harry Rogers came along and said “What’s all this about you looting Garth?” I explained the situation and said, “If we don’t have it, it’ll only be left for Jerry.” He said, “Yes, but we mustn’t let that get amongst the boys.” He had been in WWI and said, “I’ve seen this happen before. All the boys got drunk and the Germans just came in and wiped them out so you’d better put that in my billet.”

So I the threw down what I could and he told me to get down to HQ and out of the major’s way. I took my truck and I went down to the HQ at Amiens and on the way back I got cut off by Jerry. I was on my own. I stopped at a café, got a bottle of booze, sat on the step of the café and as soon as I sat, dogs and kids come around. This French boy came up I gave him a bar of chocolate from my so-called loot and we sat together. All of a sudden up ahead at a t-junction a half-track went by with SS on board, they didn’t take prisoners so I thought it was time to move! I made my way back to the ol’ smoke at Dunkirk.

On the way up I was challenged by Frenchmen or Belgians or some damn thing. They wanted to ride on my truck and I said no, I had a girl on board, she had asked me to take her, I cant remember where it was but there was a maternity hospital there and she was heavily pregnant so I said I would take her there and drop her off. She was sat beside me and they raised their guns. I took out my Tommy gun and said ”Right, who’s first?” and they backed off.

I went on, dropped the girl off and picked the convoy up again. It was that night I picked the convoy up that the bloomin’ truck with all my loot on and Harry Rogers’ kit got bogged down. The soldiers nearby said, “Get over this side” There was a bloke in front of me who had a fag on and all of the petrol from the truck was running into the drain. All of my salvaged supplies was on board this truck and I thought, “Why the devil should anybody else have it?” I let the bloke go on smoking and when he dropped the fag end the whole damn lot went up. All of the supplies, including booze, went up in smoke!

You received your only wound on the road to Dunkirk, how did that happen?

When he told me to put his whiskey down in his billet, it had this twisted wire I was throwing it down and it slashed my thumb!

Could you see Dunkirk at night?

At night there was a red glow in the sky. By day the oil tanks were one of the Germans first targets there was a black pool of smoke a mile high drifting along. Jerry used to come through that smoke and drive out of it down onto us. It was hell on earth on the beach itself.

Memories of Dunkirk Beach

What was the situation like when you arrived at Dunkirk?

When we got to Dunkirk we were encircled. We finally got to Dunkirk and all the static guns in Dunkirk had a direct hit with the crew on the sandbanks surround. Everybody picked that out first so accordingly we went around as free agents going up and down keeping mobile all the time. The column was being led in by Ken Stephens, he was a dispatch rider. He was leading the column into Dunkirk and the Stukas bombed the head of the column. Poor old Ken was blown off his bike and killed by the side of the road. He was followed up a 1,500-weight with Tiffy Hicks, a sergeant, an artificer, a gun-fitter and a driver. They were all killed and the boy on the tailboards was severely injured. They’re all in Dunkirk cemetery.

We went into Dunkirk and we kept on the move giving what cover we could for the evacuation but we had to keep on the move all the time, keeping mobile up and down the beaches, getting into action and trying to give Jerry as much as he was giving us. We didn’t do a bad job.

When Ken was killed he was the despatch rider and we had no other riders around so I took over the job of being despatch rider keeping touch with the outlying guns. I did that for 48 hours or so between what we had for a headquarters in Dunkirk to the outlying guns around Bray-Dunes. I did a little bit of despatch riding then I dug in my own little pit.

Did a bullet hit your motorbike?

Yes it did. When I was the only one that could so a bit of despatch riding and the other riders were killed I took a bike and I was commuting between what we had as a HQ in Dunkirk to the outlying guns at Bray-Dunes. I used to have to go along the canal and you could only get 49mph out of the old thing. I used to head down and just pray because a sniper had a go at me twice and once hit the frame of the bike.

Did it stay in the bike?

It pinged and glanced off and I could see it on the frame.

How did that feel?

It was one of my more worrying moments of the war.

What was it like on the beaches?

The Germans timed bombing attacks every half hour on the tip of the half hour. He would come over strafing with his Me109s and bomb us with his Stukas. You could set your watch, on the tick of every half hour through daylight hours. Nothing happened at night but as soon as dawn broke until sunset they were over. It was so damn frightening that I was beginning to wish that the next attack would be my last. I thought, “I’m not going to get out of this so lets get this over with.” I honestly felt that way, it was terrifying.

How long were you on the beaches for?

I was up and down to the guns on the motorbike for a couple of days and I was on the beach for about 24 hours.

The evacuation is famous for the ‘little ships’ that came to rescue Allied soldiers. Did you see any of them?

Oh yes quite a lot. There were bloomin’ great queues for the little boats and I thought, “I’m not going out and waiting for that.” I just stayed in my trench and waited. I picked the right deal I think but quite a lot got away with the little ships.

I go over (to Dunkirk) every year now and the little ships…there’s none of the original owners left, they’ve all died off. You’ve got to be a millionaire I suppose to own one now-it’s quite an exclusive club. The ones that are around still are in immaculate condition and of course there is the old vintage cars they meet up with the little ships every year in September and go up the Thames to have a bit of a meet up.

The ‘little ships’ are famous but you were evacuated on HMS Codrington. Can you describe your rescue?

Yes I was very, very lucky, I was just sitting waiting for whatever came next and they came for volunteer stretcher bearers.

They say don’t volunteer for anything but I’m damn glad I volunteered for this one! I came up, anything rather than just sitting there waiting to be the next one picked off so I got up. Me and another guy picked up what was left of this poor lad and took him out along the Mole. That had been badly bombed but repaired as much as they could so you could still get access to the destroyer laying off there: HMS Codrington. We took this boy aboard the Codrington and put him down but I don’t think he lived long. I went to go back to the slit trench but the Captain told me to stay on board. I didn’t argue too much with him and I had a first class trip from Dunkirk to Dover on the Codrington. I consider myself damn lucky that I got away.

What happened when you returned home?

The artillery was sent to Woolwich and infantry was sent to Salisbury or Alderhsot. They said that anybody that had relatives within distance could have a 24-hour pass to visit, them. My brother-in-law’s sister was at Walthamstow so I opted for a pass and went there. They took me down the local pub that evening and I felt awful, I felt like a coward because old boys from the WWI were buying me drinks as if I was some sort of hero. Some had been gassed or were limbless and I felt like a coward that had ran away. That was honestly my feelings, they were the people that I looked up to and I felt that I had run away and was a coward compared to them. But there you are, that’s war.

From there we took over the forward defence for the Battle of Britain. We were around all the forward aerodromes: North Weald, Hornchurch and places like that until the Blitz was over. Then we joined the 6th Armoured Division that formed up of the 17th-21st lancers, the old skull and crossbones boys, 15/6 lancers and quite a few armoured infantry boys. We had no armour at all, we were still naked on our blessed old Mark I Bofors and it was very discouraging going into battle and all the armour shot down the lids. We were sat there up about five-feet high, supposed to be guarding them against air attack but it was not a very comfortable feeling. We did have a mobile thing in the end, it was mounted on a Ford chassis but still no armour at all, it wasn’t a very good idea.

Reflecting on the Miracle of Dunkirk

People talk about the “miracle” of Dunkirk, do you think it was?

I think it was. We came away to fight another day, it was only 350,000 of us got away but it was the nucleus of the British Army. There’s a TV programme on now called SS-GB whose plot is that the Germans had indeed overrun us and what it would have been like here. It’s pretty gory, the way they just lift up a girl and shoot her in the head and throw her down. I think that’s the sort of life that we would have had if it weren’t for the miracle of Dunkirk.

What did you think of the Germans fighting ability?

I had a sneaking regard for Jerry: the old Wehrmacht German soldier. I think the ordinary German soldier was as near to us as any other nationality, with the exception of the SS. The ordinary German was just the same as us, the SS were a different crowd. They were nasty devils but we had some funny ones too.

The German campaign was very fast and rapid. When you look back at Dunkirk, did you attach any blame on your commanders in the field or did you just you just feel you were caught up in something you couldn’t control?

We were all in the same boat; we just weren’t ready for that type of warfare.

Garth Wright is a member and beneficiary of the Royal British Legion, the United Kingdom’s largest armed forces charity. For more information visit: www.britishlegion.org.uk For more first hand accounts of World War 2, subscribe to History of War for as little as £26.