On the evening of 19 September 1356, the heir to the throne of the England entertained the king of France in his tent, near the town of Poitiers in western France. However, this was no ordinary royal meeting. The king had been captured on the field of battle and was at the mercy of one of the most legendary figures in Medieval history.

Although he was only in his mid-20s, Edward, Prince of Wales, was at the pinnacle of his military career. His life personally symbolises the first half of the Hundred Years’ War, when England fought for the right to wear the French crown. Edward, along with his father and namesake Edward III, epitomises the martial glory of the initial English victories and gained a reputation for courage and chivalry. However, Edward is known to history as the ‘Black Prince’, and, in many ways, his conduct in France was coldly brutal to those who denied their allegiance to him.

His life was a contradictory mixture of idealistic heroism and barbaric terror. Born in 1330, Edward was brought up to be a soldier. In the Medieval world, the ideal king had to be a warrior and Edward III wanted his son to be in military training from an early age. At the age of seven, Edward had already been equipped with a complete suit of armour and in the same year the conflict that would become known as the Hundred Years’ War began. Prince Edward would spend the rest of his life vigorously, and sometimes controversially, fighting his father’s cause and his military career began in earnest at the age of 16.

Winning his spurs

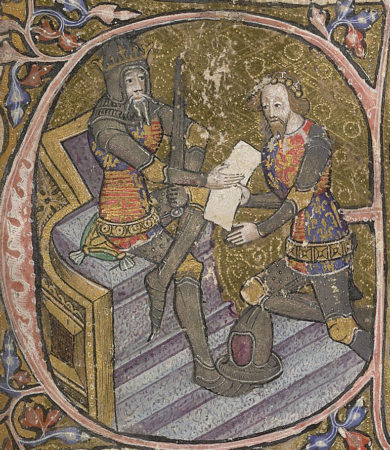

In July 1346, Edward III’s army landed unopposed in France at La Hogue. The following day, the king knighted Prince Edward to mark the beginning of his career as a soldier. The prince immediately exercised his rights to create other knights and in the subsequent march across Normandy the vanguard was nominally under his command. The French caught up with the English on the north bank of the River Somme and Edward III selected a site near the village of Crécy in order to give battle.

The English numbered between 9,000-12,000 men but were fighting a French army of about 30,000 under King Philip VI. Edward III deployed his men in defensive order on a hill with archers and two divisions in the front, and the king’s division forming the reserve. Prince Edward was in the centre of his men, surrounded by his household knights and two earls. Although the French and Genoese soldiers were continually harassed by English longbows, the brunt of the hand-to-hand fighting fell on the prince’s men.

Young Edward was in the thick of the fighting from the outset, and many stories are now attached to his conduct. It was reported that the duke of Alençon, who led the first French charge, beat down the prince’s standard before he was killed. A second French charge penetrated into Edward’s division and the prince was in considerable personal danger. Some said that he was forced to his knees and captured by the count of Hainault before he was rescued by his standard-bearer Sir Richard Fitz-Simon. In what would normally have been a serious breach of discipline, Fitz-Simon had to lower his banner in order to defend the prince.

One of the most famous stories concerns the messenger sent to Edward III at the moment of crisis to request help for the prince. The king reputedly replied, “Let the boy win his spurs.” When Edward III eventually sent 20 knights to rescue his son, he found the prince and his men resting and leaning on their swords, having repulsed the French attack.

Prince Edward’s courage during his first major engagement at the Battle of Crécy impressed his contemporaries. According to legend, he honoured the memory of the slain, blind King John of Bohemia by adopting his personal badge of three feathers as his own, which is still the symbol of the Prince of Wales today.

There was, however, a contrasting response to the knightly bravura. According to a Hainault chronicler, when Edward III asked his son what he thought of going into battle it is reported that the prince “said nothing and was ashamed”. If this account were true, then it would be at odds with Edward’s later behaviour on the battlefield.

Clash on the waves

After Crécy, the French signed a truce with the English that was prolonged by the outbreak of the Black Death but by the summer of 1350 the war resumed. English plans for an Anglo-Castilian marriage alliance involving Edward’s sister Joan fell apart when she died of the plague. The French seized this opportunity to encourage the Castilians to send a large fleet to harass shipping in the English Channel.

By July 1350, the English had assembled a fleet at Sandwich and in mid-August a Castilian host was off Winchelsea. Both Prince Edward and his father embarked on 28 August and the two fleets engaged the next evening. The English rammed and boarded Castilian ships before the crews clashed on the decks. In the fray, the king’s ship was sunk and Edward III had to scramble aboard a Castilian ship. Similarly, Prince Edward’s ship was sinking when his brother John of Gaunt sailed alongside and rescued him. The battle was a fierce contest but ended with the retreat of the Castilians at twilight, with the remainder being captured by the English.

Afterwards the king and his sons anchored at Winchelsea and Rye and conscripted horses from the towns to convey the news to Queen Philippa. It is recorded that the royal family spent the night revelling and recounting tales of the day’s fighting, which appears to be a coldly decadent contrast to the maritime slaughter that had taken place only hours before.

Edward III made much of his naval victory and the new coinage of 1351 reflected his claim to be the ‘King of the Sea’ with the martial monarch shown to be standing in a ship. As for Prince Edward, the fight at Winchelsea only served to enhance his warrior reputation, which would increase in the years ahead. His career would also begin to be tainted by a harshness in his conduct of the war in France.

“Le terrible Prince Noir”

Final truces with France ended in the mid 1350s and Prince Edward was granted his own theatre of operations in Gascony, which at that time was an English possession. The prince was enthusiastic and wrote that he “prayed the king to grant him leave to be the first to pass beyond the sea”. He formally sailed to southwest France with full powers to administer English territories there. He also received a military contract of service, which made provisions for events such as the capture of “the head of the war” (the main French commander) and the prince’s own possible capture.

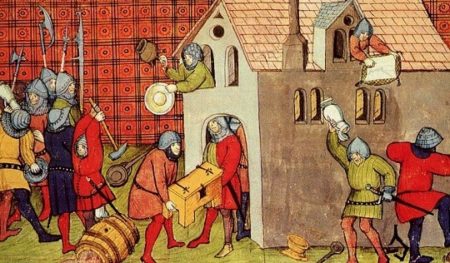

Edward landed at Bordeaux on 20 September 1355 and his combined Anglo-Gascon army of 6,000-8,000 men set out on 5 October with the aim of conducting a ‘chevauchée’ – a raid designed to weaken the enemy’s supplies and prestige by deliberately burning and pillaging towns and villages. It was effectively a form of authorised terrorism and was used throughout the Hundred Years’ War, with Edward helping to legitimise this wanton destruction.

The prince’s target in 1355 was the land of Jean d’Armagnac, who had been appointed by John II of France to put pressure on English territories. Once his army reached enemy lands on 10 October, it moved into three columns and spread out to live off the land and a fortnight was spent ravaging d’Armagnac lands. The army even had portable bridges to increase the range of the pillaging. Edward then moved into Languedoc and was able to inflict considerable damage on local towns, including the town of Carcassonne, which he seized and burned.

By 8 November he had reached the furthest point of his march at Narbonne on the Mediterranean shore where the town was taken despite fierce resistance – but its castle held out. Edward returned to friendly territory on 27 November, having not once engaged the French in open battle. The French had deliberately avoided him, making them appear hesitant and thereby giving the prince a propaganda victory.

The chevauchée was a nightmare for the people of southern France. At Montisgard it was recorded that men, women and children were slaughtered indiscriminately and this was a scene that was repeated across the region. In the 19th century, carbonised remains of burnt grain could still be found in the ruins of Montbrun-Lauragais and it was said that even the pope feared for his safety at Avignon. It is likely that Edward’s famous nickname originates from this raid – in the parts that he passed through he was known as ‘le terrible Prince Noir’. The damage was such that well into the 20th century there was a local oral tradition among regional peasants who related stories about a figure known as ‘L’Homme Noir’ who had passed by with an army in the Middle Ages.

The chevauchée also disrupted the economic productivity of the region and the French ability to withstand English attacks was consequently diminished. Edward’s steward explained, “The countryside and towns which have been destroyed in this raid produced more revenue for the king of France in aid of his wars than half his kingdom.” In December 1355, Edward justified the raid in a letter to the Bishop of Winchester: “We rode afterwards through the land of Armagnac, harrying and wasting the country, whereby the lieges of our said most honoured lord, whom the count had before oppressed, were much comforted.” Edward was implying that the local nobility were grateful for his intervention but was apparently unconcerned about the suffering that his army committed. This coldness implies that Edward only reserved his chivalric behaviour for fellow members of the nobility.

Triumph at Poitiers

In August 1356, Edward launched another chevauchée into France from Aquitaine. He adopted a scorched earth policy as he advanced north to ease pressure on English garrisons in northern and central France, but was stopped at Tours when he failed to take the castle. At the same time, he heard that John II was marching south from Normandy to destroy his army at Tours. Edward began to retreat back towards Bordeaux but the French king caught up with him near Poitiers.

At this stage, Edward offered to give up the loot his army had stolen in exchange for a safe passage but this was rebuffed. With no options left, he turned his Anglo-Gascon army of 6,000 men to face a French army of at least 20,000 on 19 September. He formed his army into three divisions with his archers on the flanks and retained his own division in the rear with an elite cavalry unit. Edward then arranged his men behind a low hedge for protection, with marshes to the left and wagons to the right.

King John arranged his own men into four ‘battles’ led by himself, the dauphin, Baron Clermont and the duke of Orléans. Both the dauphin and Clermont attacked the English but were swept back by hails of arrows and counterattacks by English men-at-arms. The dauphin’s forces then crashed into Orléans’ approaching division before running into John’s troops, which caused confusion. Had the French not panicked at this stage, they could have routed Edward’s men, who were becoming exhausted and had started to collect their wounded. Instead, Edward ordered his men to break cover from the hedge and charge the French while simultaneously launching his cavalry to flank the enemy. After a hard fight, the English stood their ground and the French line collapsed.

It was a huge victory for Edward. At a minimal cost, 2,000 Frenchmen were killed with another 2,000 captured including the biggest prize: King John II. He was brought to Edward’s tent, where the prince served him and according to one chronicler said that John’s personal bravery “had outdone his own greatest knights”. This was little consolation to John who was taken back to England in triumph.

Edward was treated to a great procession in London, where the water conduits apparently ran with wine, while John wore a sombre black robe. He had good reason to – his capture had huge ramifications in France where his ransom was more than the yearly income of the country. Some said it was twice as much and John eventually died in English captivity, with his country in a broken state of anarchy.

Into darkness

Poitiers was the pinnacle of Edward’s military career and he seemed ready to succeed his father as a powerful King Edward IV of England. He ruled Aquitaine as a semi-independent principality between the years of 1360 and 1367, and won a further dramatic victory in Spain at Nájera in 1367. Nevertheless, after the Spanish campaign his health began to deteriorate rapidly. In a highly controversial incident at the Siege of Limoges in 1370, a now litter-bound prince ordered the sacking of the captured town.

According to the chronicler, Jean Froissart, “It was a most melancholy business; for all ranks, ages and sexes cast themselves on their knees before the prince, begging for mercy; but he was so inflamed with passion and revenge that he listened to none, but all were put to the sword, wherever they could be found.” This has since been highly disputed among historians but, whatever the truth, Limoges greatly stained Edward’s reputation.

The prince’s health continued to deteriorate and he died aged 46 in 1376, just one year before his father. The once mighty prince never became king of England – his son would take that role in his place as Richard II. Edward, the Black Prince instead left a mixed legacy of military glory, selective chivalry and a bitter memory of brutal bloodshed.

For more stories of historical warriors pick up a subscription to History of War and save money on the cover price! For more information visit: www.myfavouritemagazines.co.uk