Colonel Mike Snook MBE, PhD. reveals the fierce conflict between the British Empire, Egypt and the Sudan during the late 19th Century

Between 1881-99, various conflicts and uprisings took place in northeast Africa between Egypt, Britain and the Sudanese followers of Muḥammad Aḥmad ibn al-Saiyid ’Abd Allāh. Better known as the ‘Mahdī’ (‘Guided One’) of Islam, this messianic religious leader first fought the forces of Khedivate Egypt and later the British Empire for supremacy in the Sudan.

Eighteen years of brutal war eventually resulted in the destruction of the Sudanese Mahdīst State and the establishment of Anglo-Egyptian rule over Sudanese territory. During these conflicts, both sides won significant victories as well as suffering humiliating defeats. The Mahdīsts were fierce opponents of the British and Egyptians and several famous figures from this period rooted themselves in the history of the British Empire including ‘Gordon of Khartoum’, Herbert Kitchener, Garnet Wolseley and their fierce opponent – the Mahdī.

Colonel Mike Snook, MBE, PhD. is a former British Army officer and, recognised authority on Victorian military history and the author of several books on the Mahdīst Wars. Speaking to History of War Magazine, he discusses how the British Empire became involved in the wars, the military abilities of the Mahdīsts and Egyptians and how the Sudan finally came under Imperial control.

Why did Britain become involved in the various Mahdīst conflicts and uprisings of the late 19th

Century?

Britain’s great strategic interest in the region was the security of the Suez Canal and the associated sea lane through the Red Sea. Sudan was an Egyptian colony in which Britain had no direct interest, beyond its standing moral crusade to see the slave trade suppressed all over Africa. Initially, it proved possible to uphold these imperatives through the agency of the Egyptians.

In the decade preceding the Mahdīst uprising (1881-5), Egypt was ruled by the Khedive Ismail Pasha, who thought of himself as a great moderniser, but did not enjoy the revenues to sustain his ambitions. He drew so heavily on international capital that Egypt fell into a state of bankruptcy. In a bail-out of 1875, he sold the Egyptian interest in the Suez Canal to Britain. Growing irritation at the influence of Britain and France gave rise to deepening nationalist sentiment in the army, centred on Colonel Aḥmad ʿUrābī Pasha (1839-1911). Alarmed by Ismail’s unrelenting profligacy the British and French prevailed upon the Sultan in Constantinople to dismiss him and elevate his son, Mohamed Tawfīq Pasha (1852-1892), in his stead.

Shortly afterwards Muḥammad Aḥmad ibn al-Saiyid ’Abd Allāh (1844-1885), who called himself the Mahdī, launched a revolt in the Sudan. The movement’s early heartlands were the Kordofan and the Red Sea Littoral. In the latter region Uthman abū Bakr Diqna, (c. 1840-1926), (‘Osman Digna’), acted as the Mahdī’s plenipotentiary and established a powerful hold over certain Bīja tribes. In 1882, ʿUrābī Pasha moved against Tawfīq, triggering a British military intervention in support of the khedival regime. In the aftermath of Wolseley’s victory at Tel-el-Kebir (13 September 1882), Britain set about reforming the Egyptian military.

Britain’s subsequent involvement in the Sudan came about because the Egyptian garrisons there were overwhelmed. Strategically, this was of the greatest pertinence in the Red Sea Littoral, where Osman’s following looked capable of taking Suakin. The final straw came with the 1st Battle of El Teb (4 February 1884) when the last 4,000 troops the Egyptians could field were routed by the Bīja. The former British officer in charge, Valentine Baker, now a khedival employee, was fortunate to survive. The seal had been set on events in Kordofan three months earlier, when another former British officer, Colonel William Hicks, led an army of 10,000 men to destruction at the Battle of Shaykan (3-5 November 1883).

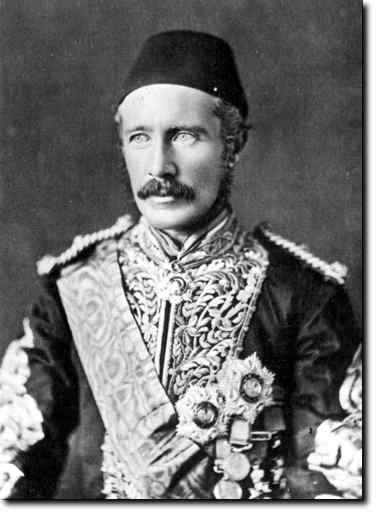

After the Baker disaster there was a clamour in London to the effect that ‘something must be done’. Reluctantly, Prime Minister William Gladstone agreed to commit a small British army to operations around Suakin. As to Khartoum, where there was still a substantial garrison in place, the Prime Minister would not be drawn beyond a gesture. That gesture was Major-General Charles Gordon, who had earlier been on Ismail’s payroll as Governor-General of the Sudan.

Gordon was now to go to Cairo and advise the Egyptians on extricating themselves from Khartoum. It formed no part of Gladstone’s intention that a British officer should be appointed as Governor-General of the Sudan, but when Gordon arrived he asked the khedive to appoint him to the governorship. With that he left for Khartoum under instructions to turn the Sudan over to self-rule. It was a tall order.

What were the qualities that made the Mahdīsts a formidable fighting force?

The Mahdīst movement was both a personality cult and rooted in fundamentalism. In Kordofan and the Littoral the greater part of the population was extremely poor, so that the movement’s foot soldiers, the ansār, were more than ordinarily ‘hardy’ souls. Because Egyptian rule had been so corrupt and exploitative, conditions were ripe for insurrection.

It is in the nature of a Mahdīst cult, of which there have been many, that authority will be heavily centralised. Blind faith in the credentials of the divinely guided one is obligatory and any doubters will be terrorised into conformity. The conjunction of Islamic fatalism, that raw philosophy which would have it that both the outcome of the day and the fate of the individual is a matter for Allah alone, with the jihādist notion that death in battle provides a portal to paradise, rendered the ordinary ansāri all but oblivious to the physical dangers of the battlefield. Therefore, the Mahdīst charge could not be checked by a modicum of effective fire. If it was to be stopped at all, it was necessary that it be literally shot to pieces with a prodigious volume of fire.

The garrison troops confronting the rebels were of doubtful quality; pressed men, spasmodically paid, poorly-led and part-trained at best. It is unsurprising that morale often collapsed, precipitating a sequence of defeats that left thousands of Remington rifles in Mahdīst hands, along with a good many artillery pieces. Thus the Mahdī’s army was always that much better armed than formerly. The Baqqāra clans provided a ready-made cavalry arm while the ansār were fearless, disciplined, unified and well-led. They manoeuvred rapidly, made excellent use of the ground and were exceptionally hard to stop. On a battlefield that’s a powerful combination of qualities.

Much is made of the clash between British and Mahdīst soldiers but to what extent has the role of

Egyptian troops been forgotten?

The Egyptian military in the Sudan was literally destroyed during the uprising and it was that which led to British troops fighting the ansār largely unaided over the 1884-5 bout of hostilities. It is important to caveat the ‘unaided’ remark with mention of the Indian, Australian and Canadian contingents sent to the Sudan. Even before Gordon lost his life at Khartoum, Sir Evelyn Wood had been appointed to raise and train a new Egyptian Army. In the interval between the fall of Khartoum and Kitchener’s campaign of reconquest (1896-98), the new army successfully held Egypt’s southern frontier against the forces of the Khalifā Abdullahi (1846-1899), the successor to Muḥammad Aḥmad.

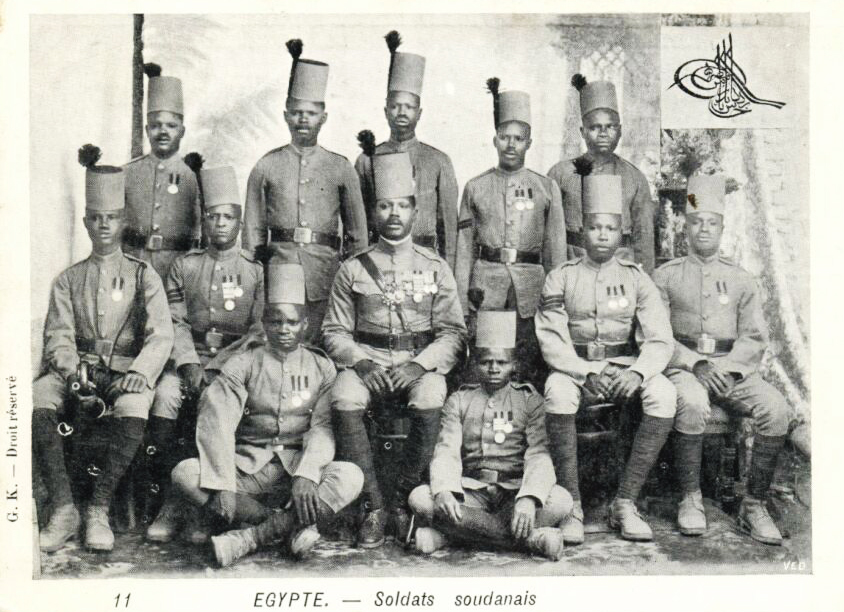

It is to Kitchener’s campaign that we must turn in order to find the new Egyptian Army (EA) at its best. It was led by seconded British officers, who ensured that their commands were thoroughly well trained and motivated. The EA consisted not only of units recruited from the Nile Delta, but also a number of first class black Sudanese battalions recruited from Equatoria and the Bahr el Gazal. Hector MacDonald’s Sudanese brigade pretty much saved the day at Omdurman (2 September 1898) by shattering an unexpected attack on Kitchener’s right. When we read of the EA we will inevitably find our noses in English language texts written by British officers, but what will be apparent from their recollections is their fondness for their men and the great faith they had in their fighting qualities. Few armies have been so dramatically transformed in so short a space of time.

‘Gordon of Khartoum’ was popularly lionised as a national hero in Britain for many years after his death. Why is he less well known in the British popular imagination today?

So too are countless other great figures of British history for broadly the same reasons. This is because of the sheer vastness of Britain’s national story with much of it arising from the prominent part the country has played in global affairs. An already vast canon, British history never stops expanding so the term ‘popular imagination’ cannot be expected to embrace all of its virtually numberless dimensions. No school history syllabus can even begin to touch on it all.

The key thing is that one doesn’t have to delve very far into the history of Victorian age, the history of the Sudan, British imperial history or military history more generally to come across mention of the remarkable General Gordon. Of course epic films can play an important part in revitalising the ‘popular imagination’ many decades after the fact with Charlton Heston’s portrayal of Gordon in the 1966 movie Khartoum fulfilling exactly such a role. Therefore, Gordon may not be so far faded from the popular imagination as the question might imply. What struck me when I was serving in the Sudan was how well Gordon is remembered there.

What lessons did the British learn from the Gordon Relief Expedition to achieve their victory

against the Mahdīsts during the Reconquest of Sudan

Kitchener would probably not have latched on to that many directly transferable lessons, because where the relief expedition had been completely governed by time, he had all the time he could ever want. That enabled him to accommodate the seasonal rise and fall of the Nile in passing his gunboats upriver and also allowed him to extend the railway in aid of his logistic effort. It is noticeable that Kitchener was taking no chances when it came to force levels. He took 17,000 men to Omdurman, whereas Wolseley, if he had made it on time, would have been obliged to fight with 3,000 men at best and might well have come unstuck. Advances in weapons technology also vested Kitchener’s force with greatly superior firepower. The Martini-Henry was replaced by the Lee-Metford, the Nordenfelt by the Maxim and muzzle-loading field guns by quick-firing breechloaders.

The result was the prodigious slaughter inflicted on the ansār on the Kerreri plain on 2 September 1898, an outcome that neither their faith nor their bravery could avert. The charge of the 21st Lancers provided a fitting end to the age of military glory.

Mike Snook is the author of Beyond the Reach of Empire. Wolseley’s Failed Campaign to Save Gordon and Khartoum, which is published by Pen & Sword Books. You can search his full bibliography at Pen & Sword here.

For more articles about the Mahdīst Wars, buy the latest copy of History of War Magazine Issue 110 (including sales and subscription offers) at MagazinesDirect.com