On 3 March 1941 Hans Frank, the Governor General, constructed a twisted mockery to that old capital of Poland’s Jewish community. Kraków had been home for up to 80,000 Jews whose roots and rituals stretched back to the 13th century, but from May 1940 the number plummeted as Frank ordered a bitter campaign of mass deportations to render the capital of occupied Poland “judenfrei.”

The remaining 15,000 Jewish inhabitants were crammed into a district previously occupied by 3,000. Behind the walls and the wire of the ghetto, Jews lived four families to an apartment. Overcrowded and unsanitary, the inhabitants were permitted only 184 calories a day of rations when the average adult requires 2,500.

In September 1941 Edward Mosberg, then aged 15, and his family joined them after his father had been picked up off the street along with nine other men and shot.

“In the ghetto they put us in a two bedroom apartment,” he recalls, “and in one room were my grandparents, my mother, my two sisters, one of my aunt with two children, and another aunt with another child. But, we were all together, still alive. I thought that life would stay like this through [to] the end of the war.”

(c) United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

On 20 January 1942 a meeting of government and security officials chaired by Reinhard Heydrich, director of the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA), set forth the Final Solution at a lakeside villa on the outskirts of Berlin. The conclusion of the Wannsee Conference was to be the extermination, whether immediately through violence or eventually through labour, of the entire Jewish population of occupied Europe.

“They slowly start liquidating [the ghetto]. They took my grandparents to the extermination camp in Bełżec. Then, they took one of my aunts with her child again to the Bełżec, and then they took my second aunt with her son.”

Though news of the extermination camps made it back to the ghettos through civilians who lived nearby, escapees or agents of the Polish Underground State, many simply would not – or could not – comprehend such a thing was possible.

“I heard the rumours, but I never believed something like this even when they sent people to Bełżec in 1942. People were saying, ‘Oh, they transport them to a new area for a work over there.’ No one knew about it because they were telling people, ‘Take everything with you because you’ll be going to a place to work.’”

(c) United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

On 13 and 14 March 1943 the Kraków ghetto was finally emptied in an orgy of violence orchestrated by SS-Untersturmführer Amon Göth. 8,000 Jews judged fit for work were transported to the nearby Płaszów labour camp. 2,000 of those found wanting – including children, the infirm or the elderly – were murdered where they stood, while 3,000 were transported to Auschwitz. Of that 3,000, 2,450 were marched into the gas chambers while the remainder were used as forced labour.

“They made us line up in the street to tell us to bring everybody, bring some luggage and put it on the street, and then they will bring us to the Płaszów Camp. I saw Germans were picking [out] people while a mother was holding a child in her arms. They ripped out the child from the mother’s arm, and they smashed the child’s head against the concrete wall, killing the child instantly. When somebody hid their child in their knapsack, they were shooting into the knapsack to kill the child. The Germans were running out with whips in one hand and a gun in the other, and shooting and picking those people [unable to work].”

Płaszów existed to supply slave labour to a network of armament factories and a stone quarry. It was considered vital to the German war effort, but subject to the sadistic whims of its commandant, Amon Göth, the death rate was high. Typhus and starvation competed with human cruelty in the race to claim the most lives. Göth, nicknamed The Butcher of Płaszów, would shoot inmates before his breakfast or order them torn apart by his dogs if he suspected they weren’t working hard enough.

(c) United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

“I worked in the offices in the administration of the officers and Amon Göth. I saw how that brutal bastard was murdering people just with pleasure. I saw him almost every day.”

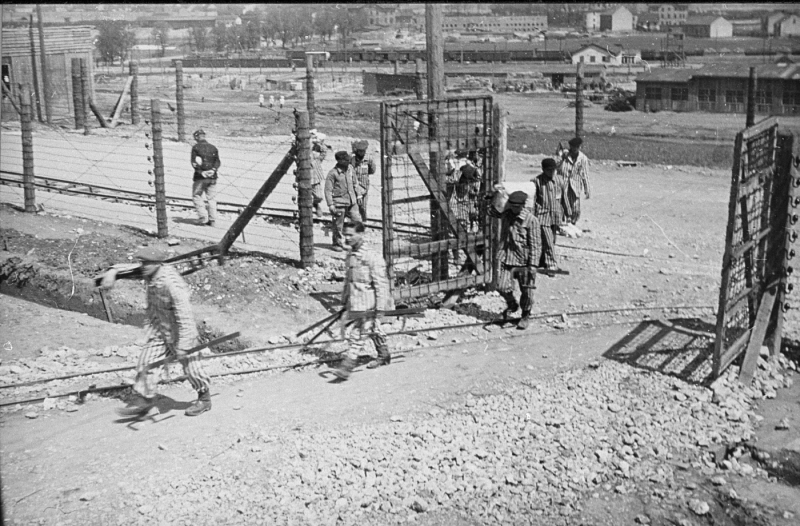

During the summer of 1944 the Germans began to dismantle the camp before the approaching Red Army. Again, those able to work were put on trains for labour camps in Germany and Austria, while those deemed too weak were driven into wagons bound for Auschwitz-Birkenau.

“May 14, 1944, they took my mother to the gas chamber of Auschwitz. I remember it like yesterday, when she waved her hands to me, and I never saw her again. This was the worst thing in my whole life. A couple of months later, they took my two sisters and the sisters of my [future] wife to Auschwitz. And then from there they took them to concentration camp in Stutthof. One night, they lined up 7,000 young girls along to the office, and they shot them with machine guns.

“I was taken from Płaszów to Mauthausen. I remember when they took us on the train, we stayed the whole night [on the rail sidings] by Auschwitz because they wanted to bring us to Auschwitz, but they told us they were too busy and they could not handle [the extra people]. [Instead] they sent us to Mauthausen. I worked in the stone mines of the Mauthausen concentration camp; 186 steps going up and down [to the quarry] from early in the morning til night. If you think you will stop for a moment, they push you to [your] death, or they beat you with their whips.”

Mosberg credits his survival with luck, but the surest chance of survival in a labour camp depended on being able to continue working in face of the brutality, exhaustion and hunger. Good health proved as scarce as good luck, but there were ways of tipping the odds.

“I always volunteer for extra work by going to the kitchen to bring container of soup, for instance. So, you have to get up early in the morning to bring the coffee. So, because I was bringing it in, so I could get the first cup of coffee [or bowl of soup]. Then, when they finish it up, I used to clean it up. And I used to eat the whatever they left from coffee there, the grounds.”

As the Allies advanced deeper into the Reich, the SS planned to liquidate the camp by marching the inmates into the underground factories and burying them alive. On 28 April 1945, under the guise of an air raid, 22,000 prisoners were marched into the complex. For whatever reason – sabotage, cowardice or conscience – the dynamite didn’t blow and Mauthausen was liberated by the US Army.

“This is my life. I never forgot this, and I cannot forgive. In Bełżec I lost 60 members of my family. When I walk through that place visiting now, I could hear the cries of my family and the rest of the 600,000 people who were murdered there: Don’t forget us. How can we forget?”

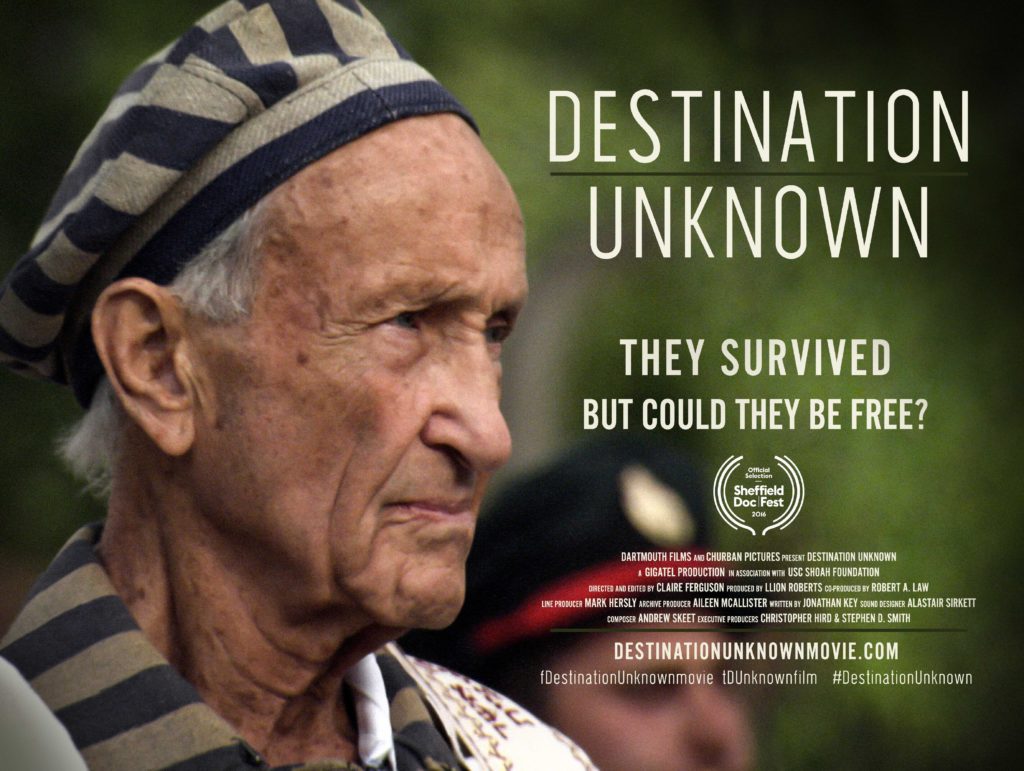

DESTINATION UNKNOWN is in cinemas 16 June http://