Having served 58 missions in Africa and Europe during World War II, Theodore ‘Dutch’ Van Kirk transferred to the 509th Composite Group. He was the navigator on the Enola Gay, which, on 6 August 1945, dropped the first atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. All About History interviewed Dutch shortly before his death last year, and he remained adamant that using nuclear weapons was the right course of action.

Theodore Van Kirk, known to everyone as ‘Dutch’, was having trouble sleeping.

It was a common affliction among soldiers before a mission, but then again Dutch and his fellow 11 crewmates stationed on the Pacific island of Tinian had more reason than most to be suffering from insomnia that night. The date was 5 August 1945, and tomorrow morning they were to drop the first ever atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

To pass the time, some of the crew – including navigator Dutch, bombardier Tom Ferebee, and pilot Paul Tibbets, played poker. It was quite prophetic considering that in a matter of hours they would be gambling again – and this time with much higher stakes. Sure, the US had successfully detonated the first nuclear device the month before during the Trinity test in New Mexico, and Dutch, like all his crewmates, had several months’ intensive training from Wendover Airbase in Utah under his belt. Nevertheless, the fact remained that what they were about to do had never before been attempted in warfare. Indeed, Dutch recalls: “One of the atomic scientists told us ‘we think you’ll be okay if the plane is 9 miles (14.5 kilometres) away when the bomb detonates’.” When challenged on his use of the word think, he said: “We just don’t know.”

Dutch had been hand-picked to join the 509th Composite Group – the unit tasked with deploying nuclear weapons – by his former commander: “I flew with Paul Tibbets all the time in England. We flew General Dwight Eisenhower (later to become US president) from Hurn (on the south coast of England) down to Gibraltar, for example, to command the north African invasion. Then we were all separated and doing various things – I was at a navigation school, for example, teaching other navigators. Tibbets was picked to take command of the 509th group and he looked up some of the people he’d worked with in the 97th (Bombardment Group).”

The history books often paint the picture that the US government and other Allied powers were hand wringing right up until the final hour over the decision to use the A-bomb. However, although Japan was presented with and rejected an ultimatum to surrender on 26 July, Dutch personally felt it was a foregone conclusion: “I knew that I was going to drop the atomic bomb from February of that year (1945). It didn’t come as a surprise. We were based on the US airbase at Tinian for about a month prior to dropping the bomb, just waiting for the call.”

At about 10pm, the crew were called from the barracks to have an early breakfast before one last briefing and final checks of the Enola Gay. Dutch remembers they had pineapple fritters because he hated them, but Paul Tibbets loved them. While he might not have seen eye to eye with his commander when it came to breakfast, he has only praise for the man that piloted the specially modified B-29 to Hiroshima – and back again.

“He was an outstanding pilot. His skill saved all of the crew’s lives a number of times in Europe and Africa. When he got in a plane, he became part of it. When you flew with Paul Tibbets you didn’t have to have your shoes polished or your pants pressed, and all that sort of stuff, but when you got in the plane, you better damn well know what you were doing!”

It’s hard to imagine what the mood on the Enola Gay must have been like as it took off at 2.45am, but from Dutch’s perspective this mission was the same as any other. “We were going a long distance over water, using Iwo Jima as a checkpoint on the way. Now, if you got lost between Iwo Jima and Japan, you really were a sorry navigator! Everybody on board was doing his own thing. Ferebee took a nap, for example, our radio operator, as I recall, was reading a whodunnit about some boxer. Everybody was making sure they did what they were there to do, and that they did it right.”

While the Enola Gay and Bockscar (the plane that dropped the Nagasaki A-bomb) are the two that have gone down in history, Dutch is keen to point out that the operation was a lot wider than that: indeed seven aircraft were involved in Special Bombing Mission #13 to Hiroshima on 6 August. Three were observational planes that flew ahead to ensure conditions were right, Top Secret was a backup to the Enola Gay that landed on Iwo Jima, while the other two aircraft – The Great Artiste and Plane #91 (later named Necessary Evil) – accompanied the Enola Gay for the full operation.

“The Great Artiste had instruments that were to be dropped at the same time as we dropped the bomb. If you were to ask me the name of them, I couldn’t tell you; I just call them ‘blast meters’ because that’s what they were measuring. The other aircraft (Plane #91) was flying about 20 miles (32 kilometres) behind with a large camera to get pictures of the explosion. Unfortunately on the day the camera didn’t work. So the best pictures we got were from the handheld camera of the navigator on that plane.”

The three planes arrived at Hiroshima without incident at about 8am. The city had been chalked as the primary target for several reasons. There were a great number of military facilities and troops there, as well as a busy port with factories supplying a lot of the materials that would be used to defend Japan in the event of an invasion. Beyond these factors, Hiroshima had not been previously targeted by Allied forces, so any damage recorded later could solely be attributed to the nuclear bomb. Tragically for the citizens of Hiroshima, it also meant the Japanese authorities had very little reason to suspect an attack there – even when the tiny squadron of three B-29s was no doubt spotted approaching…

On the actual bomb run, Tibbets relinquished control of the Enola Gay to bombardier and close friend of Dutch’s, Tom Ferebee. As Little Boy, which actually was not so little, weighing in at 4,400 kilograms (9,700 pounds), was released, the plane experienced a mighty upward surge, but Tibbets managed to stabilise the B-29 and make a speedy getaway.

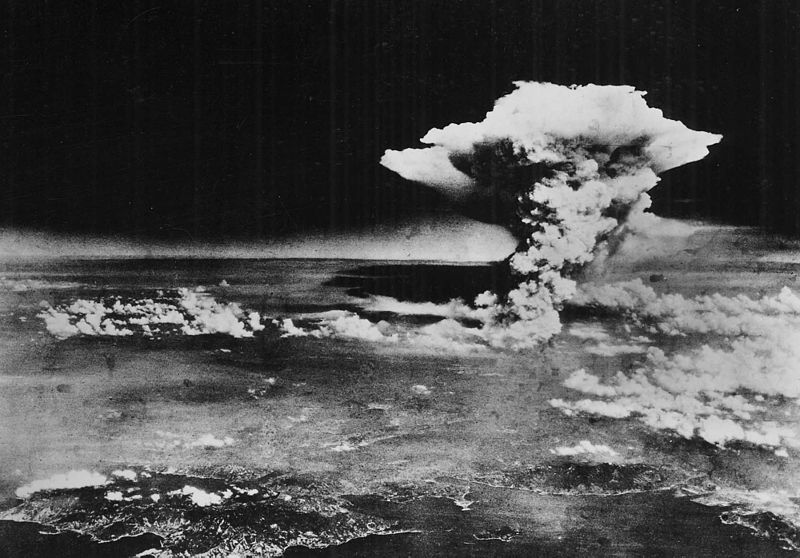

“We made the 150-degree turn that we’d practised many times and pushed down the throttle to get away. All people were doing was holding on to something in preparation for the turbulence that was sure to follow. A loose person or a loose anything in the plane was going to go flying around, so we all made sure we were in position and wearing our goggles.” They were about nine miles away when the bomb exploded, 43 seconds after it had been released. “We couldn’t hear a thing over the engines, but we saw a bright flash and it was shortly after that we got the first shockwave. When we turned to take a look back, all we could see of Hiroshima was black smoke and dust. The mushroom cloud was well above us at about 40,000 feet (12,190 metres) and still rising. You could still see that cloud 300 miles (480 kilometres) away.” What the crew of the Enola Gay couldn’t know at that point was just how destructive the atomic bomb had been. Underneath all that smoke and dust nearly 70 per cent of the city’s buildings had been destroyed and 80,000 people were dead – and that figure was set to rise with the much-underestimated effects of radiation.

Unlike the Great Artiste with its faulty camera, from the perspective of Dutch on board the Enola Gay “everything had gone exactly according to plan. The weather was perfect; I could probably see Hiroshima from 75 miles (120 kilometres) away. My navigation was only off by six seconds,” he says with pride. “Tom put the bomb exactly where he expected. We got a lot of turbulence, but the plane did not break up, which it could have done, and we got home. Now, as for the second mission to Nagasaki, everything went wrong. They had a lot of luck on that mission.”

Indeed, three days later on 9 August, a different bombing crew on Bockscar almost didn’t make it to Nagasaki due to a combination of bad weather and logistical errors. However, they managed to salvage the mission – the result of their success, or ‘luck’ as Dutch would have it, was the instant obliteration of another city and 40,000 of its inhabitants. Less than a week later Emperor Hirohito made a radio announcement, declaring Japan’s surrender as a result of “a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which is incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives.”

A few weeks after the bombings, Dutch Van Kirk was part of the crew transporting scientists to Nagasaki to measure the devastation of one of these ‘new and most cruel bombs’ first hand. “Having picked up some scientists in Tokyo from the Japanese atomic programme – they were also working on atomic bombs, you see – we flew down to Nagasaki; we couldn’t land at Hiroshima at that time. We landed on a dirt field and the Japanese commander of the base came out, looking for someone to surrender to. We were given old cars – 1927 Chevrolet models, or similar – to drive to the city centre, but they all broke down three times before getting into Nagasaki.

“There wasn’t really anything that shocked us, though there is one thing that has stayed with me. The Japanese military was being broken up at the time and one of the soldiers arrived on the bus looking for his home – but it had been destroyed. I remember looking at Tom Ferebee and saying: ‘You know, Tom, that could have been us if the war had gone the opposite way.’ I didn’t feel too good about dropping the bomb – but I didn’t feel too bad about dropping it either. This was one man among many that were saved by the dropping of the bomb” because it had precluded a full-scale invasion of Japan. “It was very important we saw that, and we both recognised how lucky we were.”

Along with all the Enola Gay crew, Dutch Van Kirk has no regrets about dropping the atomic bomb, seeing it as the lesser of two evils. Asked whether he believes the result would have been the same – that the war would have ended – if things ‘had gone the opposite way’ and Japan had dropped an atomic bomb on the USA first, there is a long pause before Dutch says, “No, I don’t think so. I think we would have been more resilient.” But underneath the bravado of the response, there’s no getting around how long he had hesitated – or the fact that, like that atomic scientist who couldn’t offer any certainties on Tinian in 1945, he had used the word think.