Providence could not have endowed a more difficult setting for India’s greatest romance. Along the periphery of the Thar Desert, beyond the undulating dunes and thorny brush, are the Rajput nations. From Gujarat in the west until Delhi and the foothills of Kashmir, there existed since time immemorial glittering kingdoms ruled by fighting men. Yet it was in the Indian subcontinent’s arid north, the realm of the harrier and desert fox, where Rajputana came to be. It was a land where rugged noblemen hunted game, built magnificent strongholds, and repelled the tides of conquest.

They are the ‘sons of kings’, divided among clans whose ancestry dates so far beyond recorded time that descendants claim divine origins. Among the Rajput clans, some trace their descent from the Sun, others the Moon, and still others believed their lineage came from fire.

Until modern times, the prevailing consensus as to the Rajputs’ point of origin was an Aryan descent from India’s mythical age. This unsubstantiated belief in a shared heritage with white Europeans later provided ample justification for the British Empire’s designs on the subcontinent. Furthermore, no single source gives a complete index of the Rajput families. The English soldier and adventurer Lt Col James Tod’s Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan is the seminal volume about these soldier-aristocrats and remains the best introduction to the subject.

Divided among three dozen clans and even more sub-clans, many notable surnames stand distinguished in the historical record. Consider the Chauhan clan, who once ruled Delhi before the Afghan conqueror Muhammad Guri vanquished them in the 12th Century. It is the Guhilot clan, however, who would conceive of India’s greatest fortress: Chittorgarh. Seized from its former masters whose fortunes ebbed with the decline of an ancient empire – of which many are found across India – the Guhilots held Chittorgarh for several centuries and grew wealthy from its country, the kingdom of Mewar.

But why did Will Durant, in his The Story of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage, compare the Rajputs to Samurai? Perhaps it was their preoccupation with honour, a trait manifested in another well-known clan, the Sisodyas, who in the early 14th Century replaced the Guhilots as overlords of Mewar. Like the Samurai, the Rajputs had their own code of conduct. Theirs was detailed in no less than the Mahabharata, Hindu civilisation’s epic poem. In it, the Hindu Kshatriya, or warrior caste, were beseeched to always fight fair and observe correctness in their doings. No conquest should be followed by plunder, no victory accompanied by the dishonour of one’s foes. Importantly, combat was a rite where cool heads prevailed. “A Man should fight righteously without yielding to wrath or intending to slay,” the Mahabharata read.

On the other hand, it was Tod the chronicler of Rajasthan who found parallels between the Rajputs and European knights, a comparison that no doubt resonated with his fellow Englishmen raised on Walter Scott and Cervantes, for whom the echoes of medieval pageantry rang with sweet nostalgia. Meanwhile, another historian, Mountstuart Elphinstone, agreed with Tod’s portrayal yet drew a different assessment of the Rajputs. “They had not the high-strained sentiments and artificial refinements of our knights,” Elphinstone concluded, while lauding their fighting spirit.

The warrior caste, defined

One of the first serious writers on India, James Mill, philosopher John Stuart Mill’s father, produced The History of British India, a groundbreaking work that sought to explain the nuances of the Hindu world.

Mill claimed that once land ownership supplanted pastoral society, it was imperative for a religious class, or the priestly Brahmin, to coexist with fighting men who would protect them: the fabled Kshatriya. “To bear arms is the peculiar duty of the Cshatriya [sic] caste,” he wrote. “And their maintenance is derived from the provision made by the sovereign for his soldiers.”

Below these exalted social strata, according to Mill, were two lower castes of common labourers and even less reputable, and not mentioned, are the untouchables.

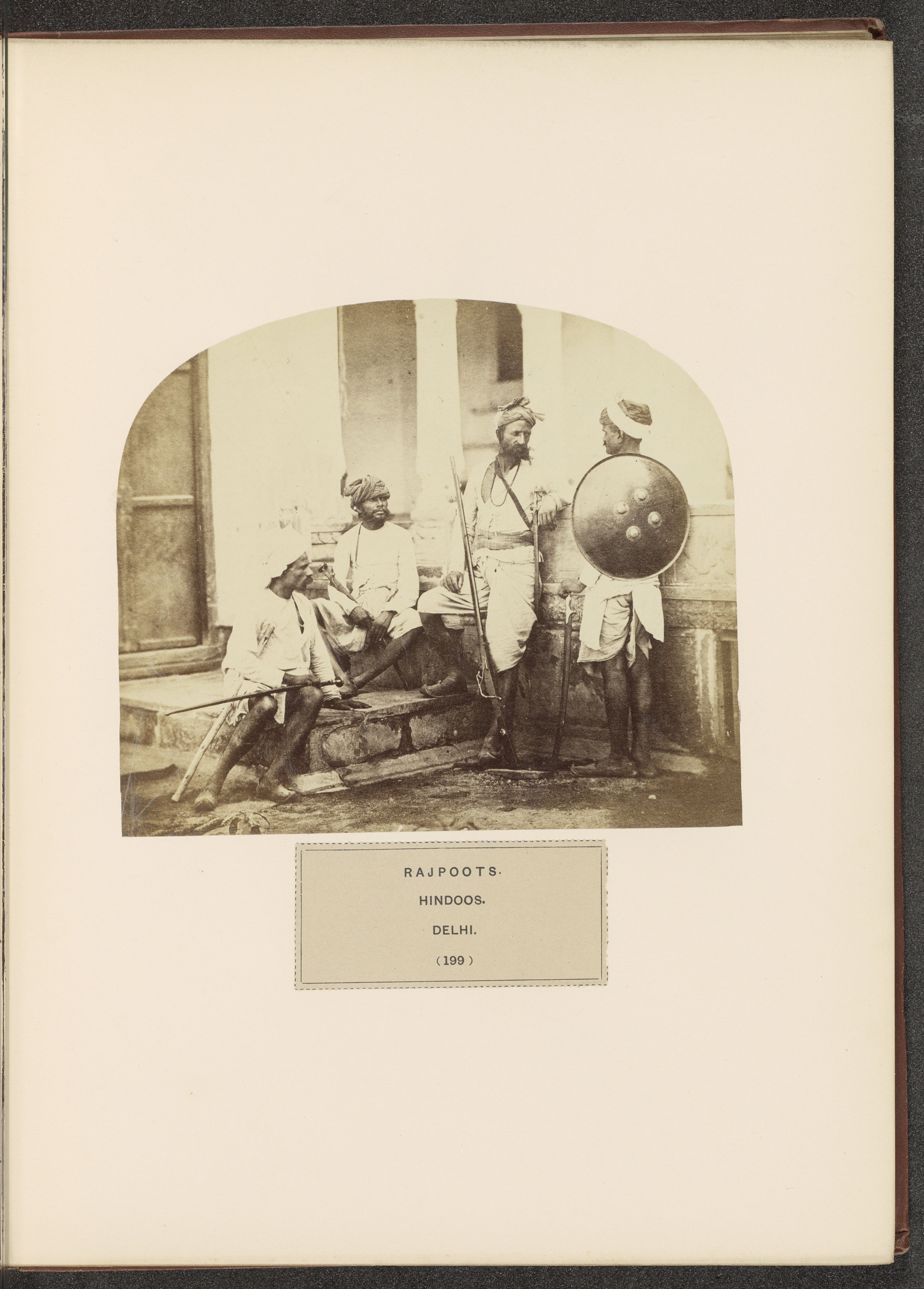

The provisions Mill referred to, in the case of the Rajput, were more than adequate. The quintessential Rajput warrior, middle-aged and seasoned by at least several campaigns, was a swarthy gentleman fond of the hunt and the pleasant diversions befitting a nobleman.

His face adorned by a flowing moustache, head wrapped in a turban dyed the colours of his clan, the Rajput was a dapper fellow. Come war time, a steel helmet crowned his head and astride his mount the warrior sallied forth with a lance and a round shield – the latter perfect for single combat.

When it came to the preferred mode of fighting, cavalry raids were a perennial favourite and very effective against their Turkic adversaries. Once mounted on either a Kathiawari or Marwari horse, Rajput formations wrought havoc on enemy formations.

Always prepared to meet his end, the Rajput fought in a shirt of mail and tied around his waist was a bright coloured sash that held two sheathed talwars (curved swords akin to the Arabian scimitar), and the fearsome katar dagger for dealing mortal blows at close quarters. Other warriors preferred the heavier khanda, a lengthy single-edged blade similar to a cutlass that was ideal for slicing through armour.

In later centuries the Rajputs would embrace the firearm. When the matchlock arrived in India via the Mughals, it was widely adopted and used until the late 19th Century. Despite this seeming prowess, Mill, for some inexplicable reason, was quick to dismiss the fighting prowess of Hindus. “Yet has India given way to every conqueror,” he observed.

This conclusion betrays a lapse in Mill’s scholarship. Apparently, he failed to acknowledge how numerous Rajput clans repelled invasions from the time of Alexander the Great to the Persian Nadir Shah in the 18th Century. But deriding the Hindu was a distasteful consequence of British imperialism. The irony is during the British Raj in the latter 19th Century, it was fashionable to commend so-called “warrior” or “martial” races within Indian society.

A dated but superb example is The Martial Races of India by Lieutenant General George MacMunn, written and published after the Great War. Another similar text is The Sepoy by Edmund Candler published around the very same period.

Both Candler and MacMunn were in agreement as to the valour and toughness of the Rajputs and the Jats, the Gurkhas and the Sikhs, even the “Mussulman” Pathans and the Mughals.

Constant invasion

These clans formed a prosperous civilisation, until the 18th Century when enterprising warlords across Central Asia saw India as a source of loot for their armies. The geography of the Rajput kingdoms, including Mewar, meant the Kshatriyas had no choice but to thwart these onslaughts or be dispossessed.

While Rajput cavalry could best the seasoned Turks, Afghans, and Mongols, many catastrophic defeats were also dealt by the would-be conquerors. Of ruinous portent was the arrival of Zahiruddin Babur (14 February 1483 – 26 December 1530), who sought to expand his tenuous control over Kabul by annexing Delhi and its surroundings. Babur might have perished at an early age, but he left a son, Humayun (6 March 1508 – January 1556), to finish what he started. The rise of the Mughals signalled the greatest tribulation forced on Rajputana’s kingdoms.

It was during the reign of Akbar (5 October 1542 – 12 October 1605), considered the most accomplished Muslim ruler in his era, when Mewar’s ruling Sisodya clan was humbled and their country almost ruined.

Having failed in compelling a union with his growing empire, the cosmopolitan Akbar sought to annex the kingdom of Mewar. It was sheer luck that the current Sisodya Maharana Udai Singh II was a weakling and once the siege commenced on October 1567, he quickly abandoned the fortress.

Akbar used the enormous wealth at his disposal to raise an army equipped with cannon and musket. The five-month struggle of Chittorgarh, where fighters from several clans held fast, was brutal. Despite having mined a portion of its impregnable walls and inflicted horrific casualties on the defenders, the Rajputs were unbowed. It was only their ideal of honour that doomed them to suicide at the last moment. The men died fighting while their families committed Jauhar, grisly ritual suicide by self-immolation.

Akbar’s victory was the third and last time Chittorgarh fell. Further disgrace followed in the Battle of Haldighati, where Mughal arms prevailed once again.

Their forces scattered, it was the renegade Sisodya Maharana Pratap Singh (9 May 1540 – 29 January 1597) who carried the red banner of Mewar. Maharana Pratap, as he is known today, was such an ardent rebel and tactician he became a folk hero.

Maharana Pratap’s struggle continued after his death until Akbar’s son Jahangir (30 August 1569 – 7 November 1627) grew weary of fighting the Rajputs. Sparing the sword, he signed a treaty with Maharana Pratap’s son and from then on lavished gifts upon the Sisodyas. The bewildering sums of these bribes are described with detail in Jahangir’s memoirs.

In a rare gesture of magnanimity, Jahangir even returned the regal Chittorgarh fortress to its former owners. But could the Rajputs survive the oppression of European colonialism?

They did, and it led to a new age of prosperity for these landed Kshatriyas. Once again, it is Tod’s Annals that explains why the Rajputs, having likewise suffered from the decline of the Mughals, sought help from the British Empire.

As early as 1775, in fact, a battalion of Rajput riflemen were levied by the East India Company, whose grip on the subcontinent was now uncontested after besting the French during the Seven Year’s War. By 1817 this core unit became the Rajputana Rifles, the foremost senior regiment in the Indian armed forces.

From one empire to another

It wasn’t until the 19th Century when Rajputana’s leading clans sought to federate with British India. A deal was brokered by the Maharanas and Charles Theophilus Metcalfe, a special aid to the acting British Governor-General in Delhi.

The reason was entirely practical, since by 1818 Rajputana had been economically ruined by the collapse of Mughal power, repeated invasions from Persia, as well as the resurgent Marathas who wished to carve out their own piece of empire.

Once the British controlled the whole of India, the Rajputs proved willing partners in governing the small kingdoms throughout this vast colonial possession. Their usefulness quadrupled as soldiers and allies, while the habits of the Rajput nobility also mixed well with their British counterparts.

The attraction, by any account, was mutual – this sentiment is found in the aforementioned The Martial Races of India by MacMunn. MacMunn believed the Rajputs were the Aryans of Central Asia and belonged to the same racial stock as modern Europeans. “They are the descendants of the warriors who carried forward the Aryan exodus and influx,” MacMunn concludes, before distinguishing the Rajputs from the Jats, the Tartars, and Mongols.

MacMunn also found the Rajputs to be a fair race, admiring their features that had the “Aryan beauty and physiognomy of the Greek.” In MacMunn’s view, at least, these favoured Kshatriya were white men too.

Into the world wars and beyond

Despite the understated contempt among the British for Hindus in general, the British Indian Army was a force to be reckoned with. In World War I alone, 1.3 million Indians fought in every theatre and the Rajputana Rifles distinguished themselves in France, Palestine, and Mesopotamia (now Iraq).

Come World War II, it was in East Africa where the Rajputana Rifles rose to the occasion despite the brutality of modern warfare. During the struggle for the commanding heights of Keren, in Eritrea, which was controlled by the Italians, a company from the 4th Battalion, 6th Rajputana Rifles lost its officer in a night-time assault.

Undaunted, the second-in-command Subedar Richpal Ram (20 August 1899 – 12 February 1941) led the company with “great dash and gallantry” in an uphill battle. Having reached their objective, they beat “several counterattacks” until they became low on ammunition and were forced to withdrew back to their lines.

The following day, mortally injured on the latest attempt to recapture lost ground, Richpal Ram fought and led his men until he died of his wounds. His actions won him the Victoria Cross and his name is inscribed on the Keren Cremation Memorial.

Come independence and bloody partition, the Rajputana Rifles fought every major war with Muslim Pakistan and were even deployed on counter-insurgency operations in Sri Lanka and Jammu-Kashmir.

The warrior kings of Akbar’s reign and James Tod’s book are long gone. Their weapons remain unused, their martial valour unneeded, as the noble Rajputs gently surrendered to the modern age. Nonetheless, In the first year of World War I, British General O’Moore Creagh summed up their character with exquisite praise: “They are, and ever have been, honourable, brave, and true.” His words fit the Rajputs to a tee.

For more on the military history of Asia, subscribe to History of War for as little as £26.