Speaking on its 60th anniversary, Melvin reveals how a stage musical helped to change perceptions of WWI

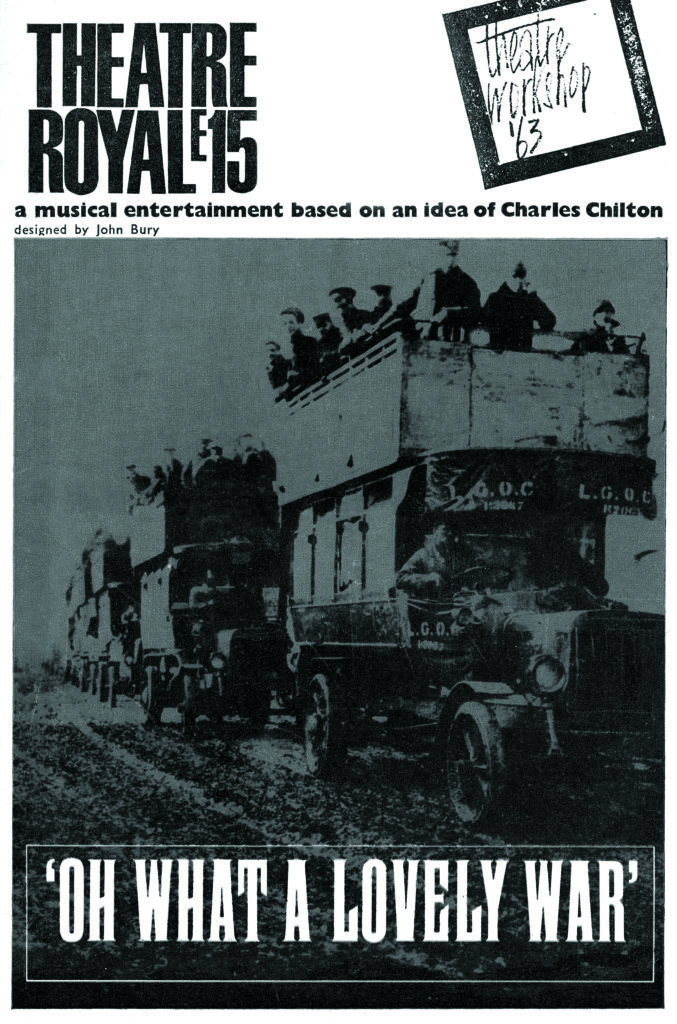

On 19 March 1963, a musical opened at the Theatre Royal Stratford East in London that radically altered perceptions of the First World War. Oh! What a Lovely War was created by visionary director Joan Littlewood and her Theatre Workshop ensemble that was based at the Theatre Royal. During the 1950s, Littlewood had leased the then derelict theatre in the East End to house the Theatre Workshop company. Her partner Gerry Raffles was the theatre manager with the Workshop presenting a variety of classical and modern plays.

Under Littlewood’s direction, the Theatre Royal became an engine house for radical fringe theatre. One notable success was the 1958 production of Shelagh Delaney’s play A Taste of Honey. A working-class tale set in Salford, the play was adapted into an award-winning film in 1961 by Tony Richardson. The only original cast member from the Theatre Royal to appear in the film was British actor Murray Melvin. A member of the Theatre Workshop since 1957, Melvin won the Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Geoffrey Ingham in 1962.

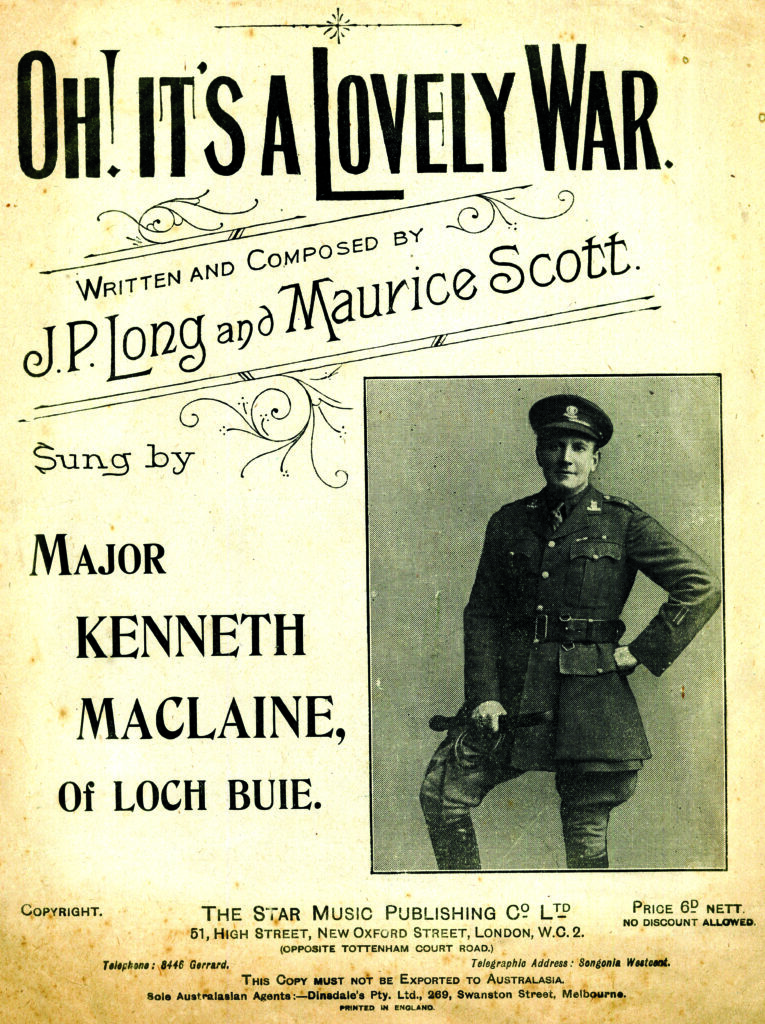

While Melvin was riding high on the success of A Taste of Honey, Gerry Raffles had developed a new production idea for the Theatre Royal. Inspired by Charles Chilton’s BBC radio programme The Long, Long Trail about the First World War, Raffles proposed a musical to Littlewood that was based around WWI songs. The result was a biting satire that was told from the perspective of the ordinary British soldier.

With cast members wearing clown costumes and harrowing images from the war projected behind the actors, Oh! What a Lovely War combined comedy and tragedy with its use of songs from the First World War. The musical’s approach was a unique departure from previous stage portrayals of the conflict with the show often reducing audiences to tears. It was also produced at a time during the early 1960s when memories of the war were still raw to many surviving veterans and grieving families.

Although critical reviews were initially mixed, Oh! What a Lovely War struck a deep chord with audiences and it successfully transferred to the West End and Broadway. Along with contemporary revisionist histories and the acclaimed BBC 1964 documentary series The Great War, it helped to change perceptions of the conflict, particularly with its bitter criticisms of the Allied high command. It was later adapted into a star-studded film directed by Richard Attenborough in 1969 and the musical is still performed today.

One of the original cast members who premiered Oh! What a Lovely War on 19 March 1963 was Murray Melvin who had returned to the Theatre Workshop. He would go on to have an acclaimed career working with film directors such as Stanley Kubrick, Ken Russell and Lewis Gilbert but Melvin has always retained a close attachment to the Theatre Royal and Joan Littlewood’s legacy.

Working as a voluntary archivist at the Theatre Royal for many decades, Melvin donated the theatre’s archive – including for Oh! What a Lovely War – to the British Library in 2021. Speaking to History of War Magazine for the 60th anniversary of the premiere, he recalls the vigorous rehearsal process and the response from audience members, including WWI veterans and Bertrand Russell.

What does the original programme for Oh! What a Lovely War reveal about what its creators wanted to achieve?

I’ve got the original programme in front of me and I still find it very moving. There’s an extended quote in it by Charles Chilton that says the following, “In 1958, I was on holiday in France. At the request of my grandmother I visited Arras in order to photograph the grave of my father – her son – who had been killed in that area. I had no idea there were so many soldiers’ cemeteries around Arras. When at last I discovered my father’s official memorial, it was to find that he had no grave. Instead, his name was inscribed upon the wall with those 35,942 officers and men of the forces of the British Empire who fell in the Battle of Arras and have no known grave.”

“What could have possibly have happened to a man that rendered his burial impossible? What horror could have taken place that rendered the burial of 35,942 men impossible and all in one relatively small area? The search for the answer to this question has finally led to this production in the sincere hope that such an epitaph will never have to be written upon any man’s memorial again.”

The programme also has sections written by Raymond Fletcher (who was the play’s military advisor) and Gerry Raffles. Raymond Fletcher wrote, “The First World War could be accurately described as being a miscalculation out of accident. The accident was the assassination of the Austrian archduke, which set in motion the military machinery of two great alliances. The miscalculation was that it would be a short, sharp war that would settle Europe’s future in a few weeks. All the carefully prepared plans for war were nullified in its first month. There was an awful military stalemate from October 1914 to March 1918, during which no attack moved the front more than ten miles in either direction.”

“A lesson can be drawn from this. Before 1914 people believed that the balance of power could preserve peace. Today, they believe the balance of terror can but accidents and miscalculations are still possible and a third nuclear world war could kill as many in four hours as were killed in the whole of World War One.”

Gerry Raffles also wrote in the programme, “Everything spoken during this evening either happened or was said, sung or written during 1914-18. Everything presented as fact is true. In 1960, an American military research team fed all the facts of World War One into their computers that they had used to plan World War Three. They reached the conclusion that the 1914 war was impossible and couldn’t have happened. There could not have been so many blunders, nor so many casualties. Will there be a computer left to analyse World War Three?”

Its good stuff when you consider that the programme was written in 1963. However, it’s also terrifying. This is because what they wrote could absolutely be applied to today, especially with what it is happening with Putin and America at the moment. There could still be some sort of mishap where an atom bomb goes off and that’s it. The programme is so interesting because it still affects me – I’m so moved by it.

What were the origins of the musical?

The original accolade has to go to Gerry Raffles. Charles Chilton worked for the BBC and did musical programmes. Charlie had lost his father during WWI and did a radio programme about the conflict called The Long, Long Trail. Just by chance, Gerry heard it at home and thought, “There’s a play there”. He thought that the unofficial musical numbers that were written by the soldiers would support a whole evening show, which of course they did.

By the time Oh! What a Lovely War began rehearsing you had already had great success with the film of A Taste of Honey. How did you come to return to the Theatre Workshop for the musical?

Whenever the call came you would go back. It meant poverty, but that didn’t matter because I knew there was a genius there with Joan. When the production moved to the West End we all thought we would get lots of money but we were actually paid on minimum wages. Nevertheless, you always went back to the Theatre Workshop and to Joan if you could. You knew the experience would be hell and drive you mad but you would learn something every time.

How did the Theatre Workshop develop the production?

We had a mountain of reading! Before everyone was called to rehearsals, Joan had done all her homework and you were given a lot of research to do. This is what you did if you worked with Joan but it was not the sort of thing that was done in the elite theatres at the time. It wasn’t done because, for example, what sort of research could you do for a Noël Coward play?

In the early 1960s, the war was still seen as something of a triumph for British militarism but Barbara Tuchman had just published her book August 1914. It was our historical treasure house so we all went out and got a copy. When you read it, you realise why the war was horrific and shouldn’t have happened. I also read Alan Clark’s The Donkeys, which was luckily a very short book! It turned out to be the text that gave precise information, which is what Joan liked.

With the research, the production developed into a story of the “muddy boots” up to the “shiny boots”. History is made by the soldiers with the shiny boots but the killing and dirty work is done by the men in the muddy boots.

How attuned was Joan Littlewood to the sensitivities of the audience?

We had initially rehearsed a scene where the latest contingent of troops went to the front singing, “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary”. During this scene, the soldiers were singing away until they all looked at each other and stopped whistling. There was this strange silence, the birds would stop singing and the soldiers would suddenly see some English troops staggering towards them. They had been gassed and blinded during the first use of mustard gas.

We rehearsed this scene for three days and did a huge Brechtian display of marching around in circles until we slowed down and saw the gassed soldiers. When we arrived on the fourth day, Joan had got a rehearsal schedule. We said, “Can we go through the marching?” but she replied, “We’re not doing that.” We wondered why but she said, “You were so wonderful but we won’t have any audience members left in the theatre after that scene. It’s too horrific – so I’ve cut it.”

Facetiously, I could say that Joan changed her vision for Oh! What a Lovely War and other shows every other day, if not hour! We had been going through a nightmare of rehearsing the same scene for three days but her instinct was on the ball. That’s why in the first act it’s all rather jolly with Fanny Carby singing “Hitchykoo” etc. The idea was to make the audience complacent as they sat there enjoying the show before the end of the first act with the song “Goodbyeee” and a big explosion. Then, for the second act, came the horror.

The musical dressed its cast in Pierrot-style clown costumes. What was the idea behind that?

Joan was of the generation that went to the seaside for a holiday. They would see Pierrot clowns performing there, which was a tradition. Her idea was that army uniform costumes were horrific and using proper guns would be more than horrific. Therefore, we used ordinary wooden sticks shaped like guns. The reason for the Pierrot costumes was that it made us – the actors – removed from the horror. It was actually three times removed: actors playing Pierrots playing soldiers.

We may have worn an army hat for certain scenes but we never wore a full uniform. I later went to see a performance where they were using real rifles. I told the people who had put on the show that they’d kill the production because Pierrots don’t go around carrying real guns.

Joan was a genius because she knew uniforms and realistic weapons were unacceptable. She didn’t like death on her stage, even in classical theatre. Her reasoning was that nobody would believe an onstage death because you’d have to come back and do a matinee the following day!

What roles did you play in the production?

I had multiple roles and loved it. For example, Brian Murphy played one of the troops in the mud but he would then put on a belt and become Field Marshal Sir John French. We would change characters by just putting different belts, hats or shoes on.

How effective were the projections of real WWI images compared to the comedic style presented by actors on stage?

It was very effective because that sort of thing had never been performed before. We actors did not know what the effect of the WWI slides would be. We had no idea and because we were looking out front we never foresaw their impact.

Oh! What a Lovely War premiered at the Theatre Royal on 19 March 1963. What are your memoires of the first night?

The first person to come into the dressing room after the first show was my old chum Barbara Ferris. She was not in Oh! What a Lovely War but she was a member of the company and acted in Sparrows Can’t Sing. We were excitedly saying to her, “What was it like?” but she had a shocked look on her face and just stood there dumbfounded. She said, “You do realise this show will go on forever, don’t you?” That was the first time we realised that perhaps we had got this enormous success.

What was the audience and critical reception like?

Well, we’re still talking about it! Nothing had been seen like it before because it was “anti” the then social theatre. There was no set, it was just lighting and it ultimately changed perceptions of the war.

How did WWI veterans respond to the production?

We had a lot of veterans who came to see it. When they returned home from the war they never talked about their experiences. There were stories of wives who said that their husbands would wake up in the night screaming but they would never talk about what happened – until Oh! What a Lovely War.

This was because they had to admit that the play was right. They started to open up a bit more but because this was 1963 they did it in a different way than they might today. For example, you would go to the bar after the show and they’d come up and say, “Well done, someone is telling our story at last.” You’d ask them, “Was the war like that?” and they’d say, “Oh yes, but even worse.”

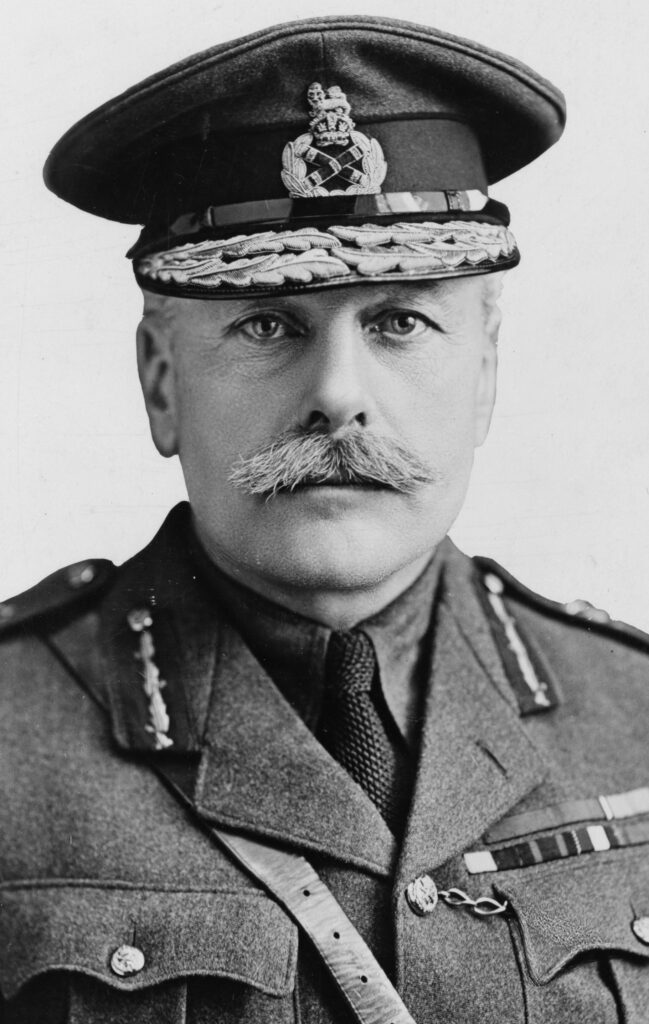

Field Marshal Douglas Haig’s command during WWI is heavily criticised in Oh! What a Lovely War. How did his family respond to the production?

The timing was right for us because the British government’s WWI documents had recently been released. We were able to directly say in the programme, “All these words are true”. At that time, Haig was heavily associated with the Poppy Appeal, whose charity is still called the Haig Fund. He had a statue in Whitehall that was saluted by everybody but he was a monster.

Poor George Sewell – who played Haig – would very often get instructions from Gerry Raffles saying, “They’re in tonight”, by which he meant the Haig family. George would come over to me and say, “Listen mate, would you go over my lines with me?” I would say, “George, you know your lines” but he would reply, “I know, but…” So we would go over his lines just to reassure him because Gerry had said, “Watch what you say George because if you get one word wrong, they (the family) will close us down.”

It was as severe as that and poor George used to be sweating out of fear. I would say, “Come on then, let’s go from the top” but of course he knew all his lines and the family never got him to make a mistake.

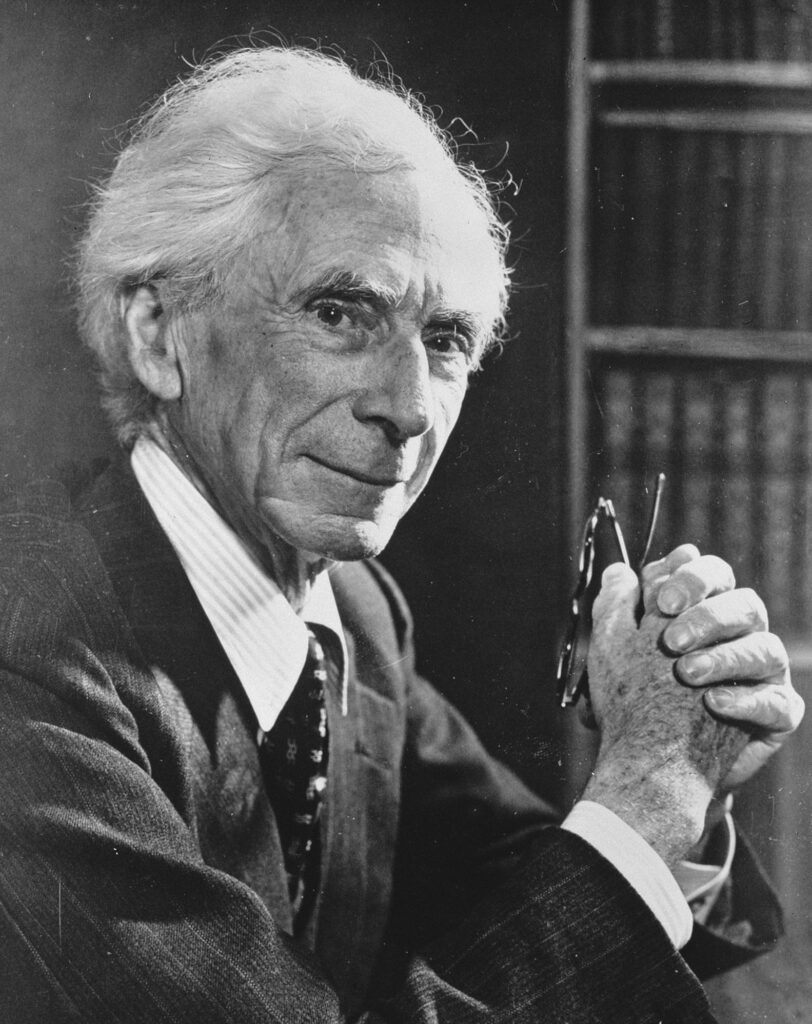

The philosopher Bertrand Russell had been convicted and imprisoned for anti-war campaigning during WWI. What did he think of Oh! What a Lovely War when he saw it on his 91st birthday?

We knew he was coming and he sat in the front row. He used to speak at Speaker’s Corner, Hyde Park as a campaigner against war and one day somebody set fire to his stand. When he saw the play he was very moved. At the end of the show Gerry Raffles got all the young ushers to come in and lay white flowers around his feet to take the place of the flames.

I can’t tell you how moving it was. We knew he was in but the audience didn’t know. There was an enormous reaction from them when an announcement was made onstage and they realised he was in the front row.

He was in tears and as soon as the show was over he left. We had planned a lovely meeting with him backstage but he was too emotionally rocked by it. It wasn’t until a couple of weeks later that he wrote a letter to us, which Gerry Raffles gave us all a copy of. He wrote in it, “I was so moved. I can’t believe that any government would allow you to show this to the general public…Oh! What a Lovely War brings war within our grasp, which is immensely difficult.” The letter is now in the archive at the British Library.

There are 14 boxes of material from the Theatre Royal’s archive in the British Library relating to the original production. Are there any materials that stand out for you?

The complete archive includes everything that has been on the main stage since the theatre opened on 17 December 1884 through to 2017. I decided that the archive should be placed in the British Library because it’s just down the road from the theatre.

At first, the British Library just wanted the material relating to the Theatre Workshop. However, I told the British Library that they couldn’t have the archive unless they took all of it. It means much more if you’ve got that pre-1914 stuff and especially from the First World War itself.

During WWI, the theatres were still open whereas they were closed during WWII for safety reasons. It’s interesting to see the productions Stratford East put on during 1914-18. Initially their tone was patriotic such as, “We will win, good old England…” but as the war went on that changed to “A Mother Lost Her Son” with themes that involved deep grief. The patriotism during the early part of the war was extraordinary.

Out of the 14 boxes relating to the production, I would think that the letter from Bertrand Russell stands out the most. It still moves me.

What do you think of Oh! What a Lovely War’s legacy 60 years after it premiered?

This was the first time in theatrical history that the war had been told from the muddy boots up. It was told from the common man’s perspective rather than the grandeur of high society and that frightful old Haig.

It still has a resonance and it’ll be forever there. From a practical point of view, it has wonderful parts for actors but ultimately it is the songs that are the show. That’s what Gerry Raffles first heard on Charlie Chilton’s radio programme. He heard those songs and thought, “Wow, that could be on stage”. Out of that came the show and here we are talking about it 60 years later.

For more information on Oh! What a Lovely War pick up a copy of History of War Issue 118 to read an interview with Eleanor Dickens, Curator of Contemporary Literary Archives and Manuscripts at the British Library. To subscribe to History of War visit MagazinesDirect.com

Further Reading

- Joan Littlewood, Oh! What a Lovely War (Methuen Drama, 1967).

- Murray Melvin, The Art of the Theatre Workshop (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2006).

- Murray Melvin, The Theatre Royal: A History of the Building (Stratford East Publications, 2009).

- Peter Rankin, Joan Littlewood: Dreams and Realities. The Official Biography (Oberon Books Ltd, 2014).