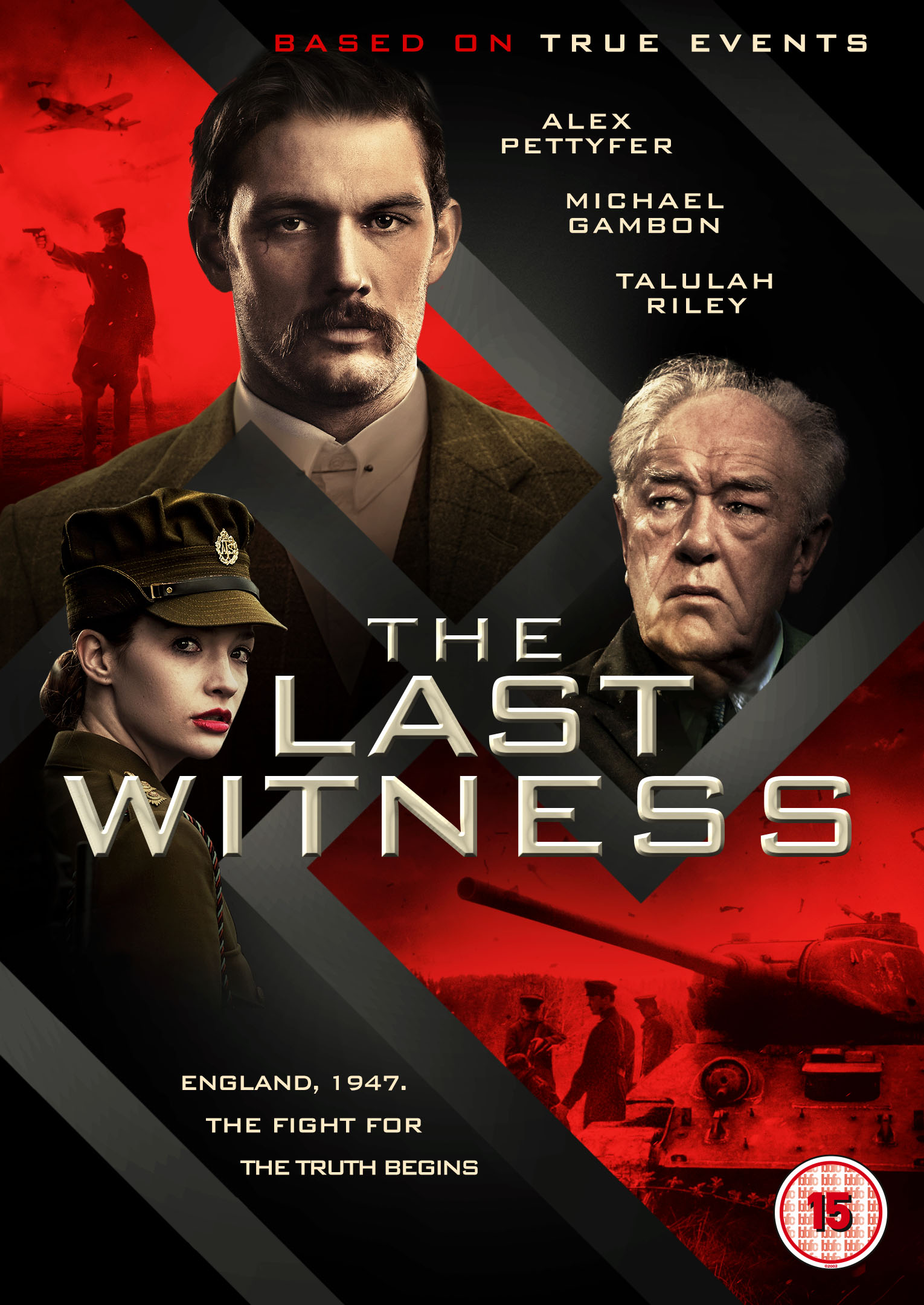

Based on true events, director Piotr Szkopiak’s new film, The Last Witness is a historical thriller set in post-war England 1947. It follows an ambitious British journalist, Stephen Underwood, as he uncovers a multi-layered conspiracy, concerning the harrowing murder of 22,000 Polish officers, executed by Stalin’s secret police in 1940, and is today remembered as the Katyn Massacre.

The film is supported by a strong cast; Alex Pettyfer (Magic Mike, I am Number Four), Michael Gambon (Harry Potter), Talulah Riley (Westworld), Robert Więckiewicz (In Darkness), Piotr Stramowski (Pitbull), Will Thorp (Coronation Street) and Henry Lloyd-Hughes (Indian Summers).

Documentary filmmaker Marianna Bukowski met with Piotr Szkopiak, to talk about the making of the film, his personal connection to the subject, and the responsibilities of finding the right balance between fact and fiction in historical films…

To celebrate the release of The Last Witness on DVD & Digital, Signature Entertainment is giving away a war movies bundle worth £20. Read on for your chance to win!

How did you set about adapting the real history, as well as the Paul Szambowski play, to the big screen?

We’ve all watched that film where it where its ‘based on a true story’ and they have bastardised everything. Here, because it’s personal history, Polish history, I have got a huge responsibility, in telling that history as factually as I can, but also I’m trying to make a film, an engaging film.

So this is where the idea of making it a thriller came in to it. It’s ultimately a murder mystery. And that is how we approached it. I have to say, I didn’t set out to make a film about Katyn. It is about Katyn by default, because we are seeing it through the eyes of the witness.

He is witness to the massacre, but I’m not telling those details. That is a massive story in itself and Andrzej Wajda made that film [2007’s Katyń]. I didn’t want to make the same film.

I saw Paul Szambowski’s play, on which the film is based, in 1995. I didn’t know the story of the last witness then. I knew about Katyn, but I did not know about Michael Loboda, and him being [in UK] and him being found hung, outside of Bristol. That is a true story.

Paul fictionalised his play around this story. Everything in the film, about Loboda, is true. Except for the one obvious thing, because I have no evidence of that. Officially it is recorded as a suicide.

When Paul looked into it, in a way just like [the film’s fictional protagonist] journalist Stephen Underwood, he came to the conclusion that it probably was not suicide. That’s where the story came from.

Underwood is fictional but Loboda, the last witness, is the core. I had some reactions where some people think the true story is Stephen Underwood. Clearly he is a believable character!

It’s through Underwood that the audience makes the discovery of the Katyn Massacre and the political cover-up, which for a British audience may not be as familiar a subject…

Completely. That’s exactly that. The audience is “Stephen Underwood”. Stephen Underwood knows nothing about this, and he discovers it. And they, the audience, along with Underwood, discover the story, uncovering it all.

It was made for an English audience that may know nothing about Katyn. I want you to enjoy it as a thriller, a film noir, a piece of cinema. The fact that it is about Katyn, and all those facts are true, is a bonus.

You can see it purely on a filmmaking level, a historical level, a political level – It is still politically relevant. I’m not telling a story that has finished. The story has not come to an end yet, and it’s still a sensitive subject.

Those borders drawn at the end of the war knowing what the Soviets had done, they were not the good guys.

As the character, Pietrowski says in the film’s beginning: “Everyone’s forgotten that it wasn’t just the Nazis that started the war” and I find myself saying that so many times. Everyone always says: “When Germany started the war…”

The Germans started the war, and the Soviets were in on it. Germans and Soviets shaking hands on the demarcation line. They were in on it together!

After Germany invaded Poland, Britain declared war on Germany, but 17 days later they should have also declared war on the Soviets. The Soviets were already the bad guys right from the start, and it’s kind of been whitewashed out of history. The Russians were never true allies. It’s grey history. It’s not black and white.

What was the most challenging in bringing this story to the screen?

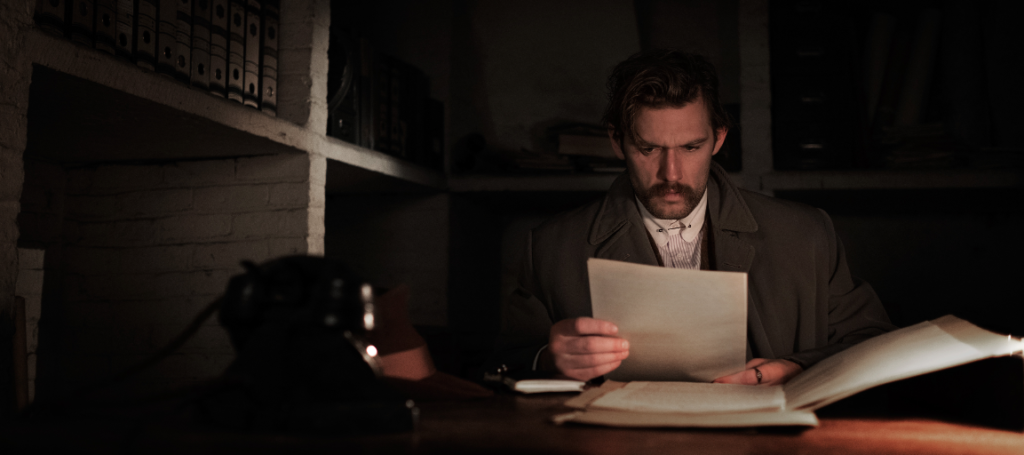

It is just difficult to make a film. I’m not helping myself by setting it in 1947, by having this many characters, where everything in the frame is period. It’s not an idea you can just go on the street and shoot. The practicality and the technical challenge of creating 1947 – that was the biggest challenge!

And you have to believe the visuals. If you don’t, it takes you out of the story. We had to be solid in every aspect. Getting this right is very important, as I am telling a true story. We had to be spot on. If the smallest thing is wrong its: “Oh, if they couldn’t be bothered…. Then why should we believe the really important stuff…”

You dedicated your film to the 22,000 Polish officers that were murdered at Katyn, and there is also a personal connection to the event for yourself?

My grandfather was on the border force and was captured and put into camp with all those officers. My mom, being an officer’s daughter, was put on a train and deported to Siberia. Once Germany invaded Russia, an amnesty was given to the Poles and General Anders brought his people out.

All Poles were left to the their own devices to leave and my mom managed to get out – she went to Persia, Africa, Palestine… and in 1947 she came to Britain. It’s the story of every post-war immigrant.

How does the film deal with the question of post-war resettlement and the heartbreaking fact of many people committing suicide after the war?

The Brits were saying: ‘The war is over – Go Home!’ And the Poles were going: ‘No, not really, you gave Poland away to the Russians, so the war for us is not over!’

Same for the Polish Battle of Britain pilots. All the free Polish forces were stuck. Yeah, politically the Poles were a problem. In 1947 the Brits formed the Polish Resettlement Act to get them out of uniform and into civvies. It was a question of which country could take you – which is the classic refugee story.

And the suicides were real. There were a lot of Poles that committed suicide. News were coming in their whole families had been killed, they had just fought for six years, traumatised after the war…

The Poles were forced refugees. They could not go home. They became political refugees. My mother was not going to go back to the country that is occupied by the same people who killed her father and deported her to Siberia.

And the Poles that did go back were imprisoned or worse.

It is an interesting story to tell and also a story that is vital to tell, because people do not understand. Politically saying “Poles should all go home!” That’s exactly what was happening in 1946 and it’s happening now.

These subjects are still politically relevant, and those same kind of issues are cropping up now in today’s politics. It is an uneducated take on immigration.

Let’s picture a situation that this was 22,000 British officers. I think things would have been different. If the Russians had killed 22,000 British officers, then Britain had been given away to the Soviet Union after the war – no one can even imagine that.

Given the weight of history in telling the story of a tragedy like The Katyn Massacre, did you face any formidable challenges or feel a considerable responsibility as a filmmaker?

My responsibility is huge. Not just to an audience, which has come to see a good film. It’s the historical accuracy. It’s the fact that it’s so important to Poland. And I don’t live in Poland – so I’m kind of taking a bit of Polish history and they are not going to be happy if I don’t treat it properly.

In the same way, I dedicated it to my grandfather, who is my mother’s dad. If I have not treated this film properly, or if she does not like it or if she is not happy, then I have to live with that as well.

All you can do is try your very best. In the end – I made [the film] for my mother. She is still alive and she is sitting next to me. It’s a living history.

I’m sitting next to the daughter of one of the officers. And it’s still affecting her. And through her it’s affecting me quite clearly. And so the duty is to that generation. To this day this story has still not come out. People still clearly do not know about it. The more important the story – the more difficult it is to tell.

The Last Witness is available now on DVD and digital platforms. For more insights and analysis from World War II, subscribe to History of War for as little as £13.

For your chance to win a Signature Entertainment War Movie Bundle worth £20 (containing: Another Mother’s Son, Wings of Eagles, The Exception, Man Down) just answer the following question: