Æthelstan (popularly known to history as ‘Athelstan’) was the grandson of Alfred the Great and from 924 to his death in 939 he unified the disparate Anglo-Saxons to create a truly unified kingdom of England for the first time. He was the eldest of son of King Edward the Elder but his mother was a concubine and his accession, as “King of the Anglo-Saxons” was by no means guaranteed. Nevertheless, once he gained power he fought relentless campaigns against his Viking and Celtic enemies within Britain and forced them all to submit to his overlordship in 927. He was now “Emperor of the world of Britain” and his rapid conquests bred great resentments among his enemies that culminated in a ‘Great War’ in 937.

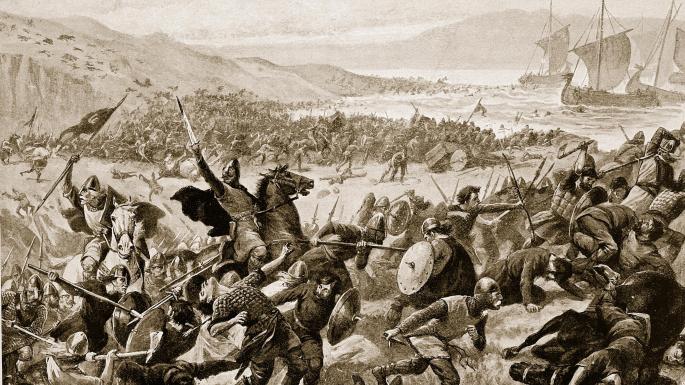

Led by the Viking king of Dublin, Anlaf Guthfrithson and Constantine II, King of Scots, an unprecedented alliance of Vikings and Celtic peoples from across the British Isles invaded northern England and captured York. Although the details are uncertain Æthelstan eventually raised an army and comprehensively defeated the invaders in an “immense, lamentable and horrible” battle at ‘Brunanburh’. Although the location of this mysterious battlefield remains unknown it was nevertheless decisive. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes how Æthelstan’s warriors were, “eager for glory, overcame the Britons and won a country.” In other words, the new kingdom of England was secured.

Despite his importance to English and British history Æthelstan is a largely forgotten king in the popular imagination. Now, over 1,000 years after the warrior king’s great victory at Brunanburh the historian, broadcaster and Anglo-Saxon expert Michael Wood spoke to History of War about an England that was ravaged by decades of savage conflict and a monarch whose military achievements made him “renowned through the wide world.”

How long have you been researching the Anglo-Saxons and Æthelstan in particular?

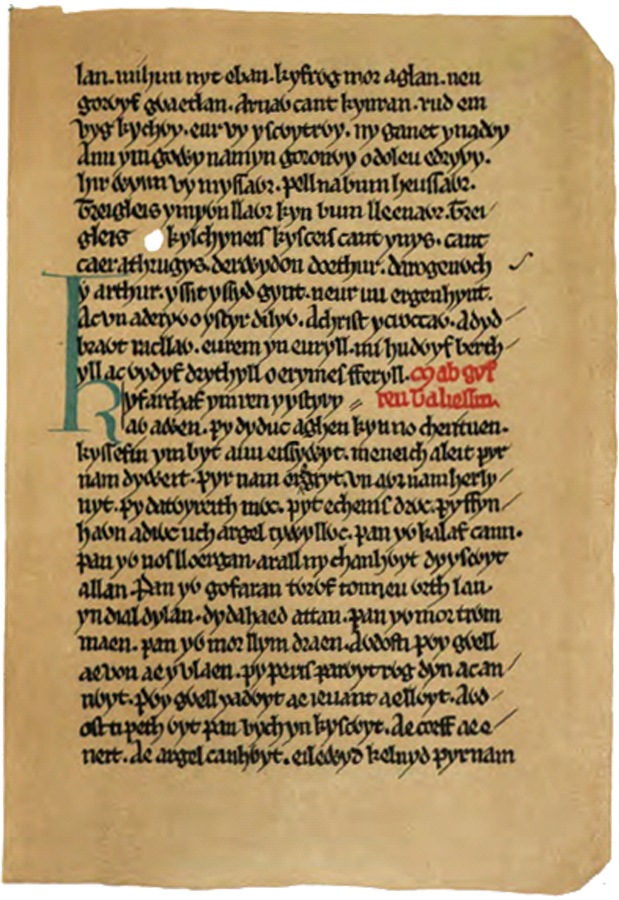

I was at school when I read Frank Stenton’s Anglo-Saxon England, which is still a really great book and was published, amazingly enough, in 1943 in the middle of WWII so it carries the mark of that as a book. Stenton has a brilliant account of Æthelstan. His reign was not very well known until that point because the materials for it are rather diffuse and fragmentary. The only thing that had been written about him before that was really great was a lecture done by a famous writer on the period called Armitage Robinson in 1922. He showed how you could look at fragments in burned manuscripts and relic lists to get into the psychology of the king.

But what Stenton did was provide an account of the wars and drama of Æthelstan’s reign and its huge achievements. A massive leap happens and its a really important moment. It’s the first kingdom of all England that’s created in 927 and the influence that this would have upon the state and its organisation and English law is massive for the future. However, it’s so problematical because there’s so little that survived except in a diffusive way.

Stenton pointed out in his bibliography that Æthelstan was the greatest person in British history for whom no biography had ever been written. I was already mad about the Anglo-Saxons since I was very young so I thought, “That’s something I would really like to do”. So I went to Oxford to do History and I actually stayed on to do research for a doctorate on Æthelstan. I didn’t stay on as a academic and instead went into television and journalism and started making films but I carried on writing academic articles. I’ve written about a dozen academic studies of Æthelstan over the years along with the more popular books so I still continued to publish stuff like that.

Two books on Æthelstan coalesced: one on the mystery of the key source and the other was a panoramic account of his whole life, which inevitably involves a lot of speculation with his early years because the most important thing is that he’s born in the reign of his grandfather Alfred the Great.

Alfred invested him with a sword, scabbard and cloak when he was aged about five in an omen of his future kingship but he was 30 by the time he became king and he only reigned for 14 years so most of his life was actually before he became king. We know hardly anything but a few things about that time so it’s a really intriguing period. Its obvious that something really big happened then but historians have never been quite sure what. So the work that I’ve done over all these years-longer than any TV programmes-is to try and untangle the material because it seems to me that its impossible to write an account of Æthelstan without having solved some of these crucial questions.

In the interim other people have done books on Æthelstan but none of them have solved these problems. Even a famous professor like Sarah Foot hasn’t solved those problems so it seems to me that until you’ve solved them you can’t write a really realistic story of the reign. One of these is what happened in the ‘Great War’ of 937, which is such an important event in 10th Century history.

“A SOCIETY GEARED TO WAR”

To what extent does Athelstan bear comparison to his grandfather Alfred the Great and his other forebears in creating the kingdom of England?

I view it as a family project over three generations. The kingdom (of Wessex) was nearly overrun in 878 before the Battle of Edington and Alfred, from a very small base, creates a “Kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons”, which was a union of the Mercians and West Saxons.

Alfred’s son Edward and daughter Æthelflæd then work together in one of the greatest combined operations in the whole of Dark Ages warfare when they reduce the Danelaw up to the River Humber. Æthelstan must have fought in those wars from the age of 15 onwards but we just don’t know.

We know from the surviving fragments that he was trained as a warrior. One source says he was “invincible like a thunderbolt” so he probably had a lot of experience of war in all those battles in the East and West Midlands fighting the Vikings.

A very reliable source says that Æthelstan was brought up by Æthelflæd in Mercia. He knew the Mercian aristocracy and that alliance is crucial to his ability to carry the Mercian aristocracy with him when he becomes king of the English.

In 927 Æthelstan invades and conquers Northumbria and forces all the kings of Britain to submit to him. He became not only the king of all the English and but also the king of all Britain. It’s an extraordinary idea.

How devastating was the impact of Viking raids and campaigns in Anglo-Saxon England during the early 10th Century?

If you want to know what is in Æthelstan’s head it would be the knowledge of what had happened in his grandfather’s and parents’ generation. Wessex had nearly fallen and there was this great royal family story of Alfred fighting in the marshes of Athelney. They really saw it as the salvation of England.

When you come into Æthelstan’s youth and teens there are major battles and devastation right down the country so it was a very, very unstable time. There are odd sources such as a letter from the Bishop of Winchester to King Edward saying, “We cannot possibly pay any more taxes. The estate here has only got 90 animals left. The Viking raids and the weather have destroyed us. The raids have depopulated the villages and the landscape: we beg you for no more exactions.” They’re talking about an estate within a few hours from Winchester, which is the so-called capital [of Wessex] so these little hints tell you that nowhere was safe. That’s why I would argue that the result was a society geared to war.

What was the condition of England when Athelstan came to power as “King of the Anglo-Saxons” in 924?

The condition of England is that north of the Humber there is a Viking-ruled kingdom of York that joins the kingdom of Dublin. The same kings from the same clan ruled both and it possible that the kingdom of Lindsey in what is now the bulk of Lincolnshire was also under their power.

In 924 Edward dies on campaign to suppress a Mercian revolt and his heir was not Æthelstan but Ælfweard. He was slightly younger than Æthelstan but was the son of Edward’s first queen whereas Æthelstan was the son of a concubine.

Ælfweard had been proclaimed as king not long before his father died so they must have known that his father was slipping. He was invested with the regalia of his office but he died 16 days after his father. At that point the Mercians proclaim Æthelstan as king and that’s the great conundrum because the Mercians proclaim him as king of Mercia, not Wessex. It takes a year for that to be resolved with Wessex so there is clearly a succession crisis.

It wasn’t guaranteed that Mercia and Wessex would stick together but because Æthelstan was favoured by the Mercians and was a West Saxon prince he trod both paths.

How significant were Æthelstan’s military conquests and campaigns of 927-28 and 934?

The first campaign that he fights as king is after the death of his sister’s husband the Viking king of York. Æthelstan seizes York, demolishes the fortifications and there may well have been fighting. Æthelstan then marches on to Cumbria and at Eamont Bridge the king of Scots, Strathclyde Welsh, Cumbrians and the other northern kings have to submit to him. The Welsh kings probably submitted at Hereford and there’s even a suggestion that the kings in Cornwall-the “West Welsh”- also submit. All of the kings in Britain have submitted to Æthelstan.

That first campaign of 927 is a kind of blitzkrieg and Æthelstan probably moves down to the Welsh borders near Hereford and further down to the southwest so you can reconstruct this incredible tour around Britain where he enforces an “Empire of Britain” with an army. Æthelstan becomes the most powerful ruler since the Romans and that uneasy overlordship survives until 933 when the Scots renounce their allegiance.

In 934 Æthelstan assembles a great army at Winchester and they then invaded Scotland. A Durham source says that they went along the east coast past Aberdeen and as far as the Moray Firth. The naval expedition that went alongside it went as far as Caithness and devastated it, including perhaps the Viking settlements there. It’s a sudden revelation of a military force that you never could have expected 10-30 years earlier. Its an incredible operation and extremely ambitious. They hit the most northern point of Britain, which hadn’t been done perhaps since Agricola.

Æthelstan re-establishes the overlordship but it’s probably the event that leads the Scots to put out feelers and say, “We’ve got to do something about this.” It ultimately led to the great coalition of 937.

ANGLO-SAXON ARMIES

What were Æthelstan’s traditional military duties as king?

The Anglo-Saxons expect a king to be a leader in war. The epithets of kingship that you see in the poem such as the famous one about the Battle of Brunanburh refer to the, “giver of rings”, the “lord of warriors”, and the “plunder lord”. You are expected to lead the army and the king’s presence was vital for its leadership.

The royal army, which goes on the expeditionary campaign all the way up to Scotland in 934, is a mounted army. The core is the leadership and there are about 140 major thegns (landowning warriors) in Æthelstan’s time and all of them have retinues. They would each have had several estates and they could probably take quite large retinues with them. We have no idea about the size of an Anglo-Saxon royal army in the 10th Century but it’s going to be several thousand men.

How were armies structured and raised by Anglo-Saxon kings in the early 10th Century?

We know so little about 10th Century warfare but law codes talk about the obligation of landowners who receive land from the king to provide military service including at least one mounted man for every plough so that’s a massive military obligation.

When you think of an Anglo-Saxon royal army you can of course also have a local army and that might be led by a local earl. If a shire is attacked the local thegn or ealdorman will send his leaders out to the hundreds (regional divisions) of the shire and the people who owe military service will be brought in with their equipment. They have some rough kind of training but they’re good enough to be directed by the few professional warriors (i.e. the thegns) of the shire to fight against local Viking attacks.

What weaponry and equipment would have been used at battles such as Brunanburh?

The word ‘knight’ is Anglo-Saxon and we think of it as late medieval but its Anglo-Saxon and a thegn would have had his own equipment including spears, a shield, sword, helmet, probably mail body armour and a horse and spare mounts. They form a really strong and well-armoured nucleus of the army.

The thegns have really ace equipment and the weaponry in their wills describe the value of their blades and hilts. You’ve only got to look at the Staffordshire Hoard where you’ve got dozens of aristocratic hilt decorations from an earlier period to see that it was portable wealth. These are really valuable possessions that could have included inlaid armour and ornamental helmets.

We haven’t got any surviving examples from the 10th Century but you can imagine that you’re dealing with an aristocratic elite who are trained for war. They’ve gone through military training and the army leaders have probably read tactical books by Vegetius or other Latin texts that exist from Anglo-Saxon England. It’s quite likely that they actually read classical texts on how to conduct feigned retreats for example.

It’s also hard to imagine that the army going up to invade Northumbria in 927 didn’t have a large baggage train with possibly mobile siege towers and portable bridges. We don’t know but they must have had these kinds of things and they are described in the Siege of Paris with Viking armies. You can’t conduct campaigns like that to besiege York and destroy the Viking fortifications [without them]. They must have had the equipment to do this because these are active stormings rather than a siege where you sit down and starve them out.

What is known about the common soldiers who fought below the rank of thegn?

We just don’t know but I’m sure we underestimate the Anglo-Saxons’ tactical ability because coordination, the messaging of separate units to join together on a particular day and place and coordinating night or surprise attacks are very common.

The Battle of Cynwit in 878 in North Devon is really interesting because Alfred is in deep trouble in Athelney and the main Viking army is in North Wiltshire. Instead, the ealdorman of Devon, Odda, has raised a force from the shire. It’s not a royal army but the Vikings suffer 800 dead so it’s a sizeable force. Odda was able to marshal a shire army that included enough people who in their normal lives were farmers but who had military training and would take orders from the leadership. You’ve got to have discipline and order in an army, they’re not just a load of peasants who sit down and drink beer. They were able to outmanoeuvre the Viking army, storm their defences and take them by surprise. All these things suggest trained leaders who work out what they’re going to do.

THE ‘GREAT WAR’

What were the causes of the ‘Great War’ of 937 and where does the term come from?

A chronicler called Æthelweard, who was an ealdorman in Somerset, was writing in about 980 and its quite likely that his ancestors fought at Brunanburh. He said that right up to present day men in the street referred to the “Magnum Bellum”, which you can safely translate as the “Great Battle” but it is conceivable that it is actually the “Great War”. The only reason I raise that translation is that we simply don’t know the scale of the war.

It may not just be a battle. It may be that the whole of the North was in chaos, that the devastation went right down into the Midlands, the losses were absolutely gigantic or that the war continued into the next year. There are later traditions of Æthelstan that say the Scots and Picts submitted and a Scottish source says that he sent an army north in 938. The scale of the fighting is something we just don’t know although I think “Great Battle” is more likely.

The cause of it was obviously the English empire and Æthelstan’s aggressive policies towards Britain. This included his determination to wipe out an independent kingdom of Northumbria run by Vikings from a Dublin clan. It was also immediately incited by his aggression in 934 with the army and the fleet going all the way up Scotland. At that point his enemies decided to combine.

What is known about the alliance led by Anlaf Guthfrithson and Constantine II of Scotland against Æthelstan in 937?

Two sources say that Constantine was the instigator and he had married a daughter to the Viking king of Dublin, Anlaf Guthfrithson. There’s a very interesting source, the most famous of all Welsh prophetic poems, the Armes Prydein (the Great Prophecy of Britain) which calls for an alliance of all the Vikings, Irish, Norse Irish, Dublin Vikings, the Cumbrian Strathclyde, Welsh, Cornish and everybody else to join together to defeat “the Great King.”

The specificity of the reference in the poem is key and suggests that by the summer of 934 a Welsh poet in Dyfed knew that people were calling for this alliance against Æthelstan to get the whole manpower of the Celtic fringe to join together to defeat him and of course that is what happened in 937.

Their intention was probably not to march down to Winchester. That’s not the agenda but what they would do either by treaty or battle is to restore the kingdom of York and to say, “Northumbria is our land and your kingdom stops there.” Whether they wanted to say it stopped at Watling Street rather than the Humber is another matter but the restoration of the kingdom of York is ultimately what they’re after. That would also ensure that the Scots wouldn’t have to endure English armies attacking them again.

We are still trying to piece together the evidence but in Viking terms their force was massive. When it’s said that “many thousands” were killed that’s from a very realistic source. A Northumbrian source says that 615 ships was the size of the fleet that went into the Humber. That’s not the Scottish and the North British armies coming overland, that’s just the combined Viking fleet. 615 ships is the biggest Viking fleet ever in the British Isles.

How did the invasion of Æthelstan’s territories unfold in 937?

The answer is we don’t know and I’m the first person to attempt to a tentative construction that is really based on the sources. One is this source by William of Malmesbury who gives an extended quotation from a lost poem that was dismissed as just being made up in the 12th Century. When you look at it closely it is not and there is no doubt whatsoever that what he says is a verbatim quote from a lost source.

It’s incredibly informative and clearly comes from a time not so long after Æthelstan’s death. It simply tells you that the Northumbrians submitted to the invaders under Anlaf Guthfrithson so that tells you that it’s in York or in the region of York. That then enables you to see how the rest then unfolded because other sources say they eventually gave battle with the help of Danes who were settled within England. That can only be in Northumbria or the East Midlands.

William’s source says that the invaders devastated widely with terrible destruction. The fields were burned; the ravaging and the looting were terrible-it was horrendous. At some point York submitted and the invading army must have gathered somewhere on the Northumbrian border because the fleet had landed in the Humber. From there the invaders are mounting expeditions into the Midlands but is it just plundering expeditions or an actual invasion? That’s what we don’t know.

The really interesting thing that then comes from the same quotation (which proves how contemporary it is) is that Æthelstan had previously been swift to act during danger. He was brilliant, invincible and never let his enemies rest but now he seems to have almost wasted the time. It was as if he “deemed his service done” while they ravaged everywhere and caused such destruction. That has to be contemporary and contrasts with rather homiletic sources where the king’s job was to be “seated on a high watchtower ever vigilant.”

There’s no doubt that that’s a real source telling you that Æthelstan, for all his great reputation, at this moment was strongly criticised for not immediately responding to the invasion. What you guess (and what the source actually says) is that he bided his time, presumably to gather more forces. Harold II did the wrong thing in 1066 by charging down from Stamford Bridge and immediately attacking [at Hastings] but Æthelstan wasn’t going to let that happen. He risked the devastation of stretches of his territory to make sure that he’d got enough forces to combat this. So that’s how I would tentatively reconstruct it but its pure speculation.

THE BATTLE OF BRUNANBURH

What is known about the events of the battle itself?

Not much actually. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle suggests that the West Saxons pursued the North British all through the day after the defeat but that’s just a poetic phrase and it may not mean anything. It almost suggests that the Mercians and the Viking army fought it out on the field for much longer but that’s maybe reading too much into the evidence. Certainly, the losses in the Irish leadership and the Irish-Viking army were huge and it does suggest that a sizeable part of the army was cut down on the field.

However, everyone agrees that it was a gigantic battle. The Annals of Ulster say it was, “immense, lamentable and horrible” and savagely fought. “Many thousands” of the Viking army were killed and a “multitude” of the English was killed as well so they have some knowledge of what happened. Anlaf Guthfrithson only escaped with “a few” so its an absolutely gigantic defeat and resonated in lots of sources.

What is known about the casualties of the battle on both sides?

There are various accounts of bishops and nobles killed on the Anglo-Saxon side. If one story is correct two of Æthelstan’s cousins are also named as being killed who were buried at Malmesbury.

There is a strong York tradition that Æthelstan founded Saint Leonard’s Hospital around that time and one tradition says that it was after the battle. Was this an expiation of his sins for having killed so many people or doing something nice for the Northumbrians? Who knows, and I haven’t been able to prove it yet.

On the Viking side the casualties included five kings and seven earls. The heir to the king of Scots was killed and there is an Irish source that lists a lot of the dead. The aristocracy bore the brunt of the fighting in some of these battles and they led by example. If things went wrong then the losses could be massive. Losses in leaders were often very heavy and they definitely were at Brunanburh.

How did Æthelstan’s contemporaries receive the victory at Brunanburh?

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was written within two years after Æthelstan’s death in 939, says it was the greatest victory since the Angles and the Saxons first came over the wide seas to Britain to win themselves a kingdom. That’s the historical context that they see it under and there’s quite a few other sources that see it in that light. It goes into folk legend, late medieval sagas, hagiography, miracle stories and right down to Elizabethan drama. It became a great source of legend so it’s a big story.

THE LOST LOCATION OF BRUNANBURH

Can you explain your theory that the battle site might have been at Robin Hood’s Well in the Barnsdale area of South Yorkshire?

I’ve always thought it was in that area. The first academic article that I ever published as a graduate student thought it was in that area and I still think it is because the other proposed battlefield site at Bromborough on the Wirral doesn’t have anything in it apart from the place name. The place name isn’t even called that until the 1130s-40s so there’s a real issue about it. The key thing is that the sources don’t even remotely suggest that it was on the shores of the Wirral and why should it have been? If York is the goal of the invasion why should the battlefield be at Bromborough?

However, Bromborough has become the accepted view and a 500-page casebook on Brunanburh was recently published by one of the university presses that’s clinched the whole thing but they didn’t asked any Anglo-Saxon historians to contribute. It’s just a misguided book in my view. I’m not saying I know for certain where the battlefield is, I’m just saying that proper source criticism has to be deployed.

Bromborough is a real problem; after all we’ve got a good source that says they landed in the Humber and many other sources suggest the same area. Common sense and the history of the area also suggest that so you have to keep looking.

I wrote an article in the Yorkshire Archaeological Journal as a response to the Bromborough casebook and the hardening of the opinion that this had to be it. Once it goes on the Today programme on BBC Radio 4 you think “My God!” and they’ve just completely overstretched the argument.

In terms of the potential location in the Barnsdale area on the Great North Road, I did the review of the evidence and looked at the most obvious thing that everyone takes for granted, which is the actual name ‘Brunanburh’. I started it as a footnote but I did a lecture at Liverpool University and have since circulated it to some top Anglo-Saxonists and they were all cool about it so I thought, “Right, I’ll put it out”.

If the argument goes that you’ve got to look south of York and perhaps just south of the Humber there are two names; not just ‘Brunanburh’ but this Northumbrian name ‘Wendun’. Then there is the issue of where was it? No stone can left unturned and then you discover that three of the four Anglo-Saxon chronicle manuscripts spell it with two ‘n’s instead of one and so does a very important Northumbrian source. That’s enough to put the flashing lights on to say that you just need to think about this.

That’s all I’m calling for really but of course common sense leads you and if you accept the argument that the war was fought somewhere on the Great North Road south of York into the five boroughs of the Danelaw then to find ‘Wendun’ and a ‘Brunannburh’ with a double ‘n’ in immediate proximity to each other then that’s really worth looking at.

Spelling is also a really good indicator. Even if it didn’t have that spelling you’d seriously be saying, “Well why on earth should Bromborough become so strongly supported as an argument?” These are philologists who are saying this, not Anglo-Saxon historians and it is a historical problem of sources in the end.

A POWERFUL LEGACY

Could it be argued that 937 is as important as 1066 in early medieval English history?

Some people have said that. I wouldn’t say it was as important as 1066 because that was a catastrophic rupture but it is one of the great decisive moments in early British history. The historian Frank Stenton said that the victory at Brunanburh wasn’t as decisive for the future as the Battle of Edington [in 878] but of course if Æthelstan had lost, been killed and his leadership wiped out then it would have been a very different story.

What was the impact of Æthelstan’s reign and his victory at Brunanburh?

Æthelstan died two years later and his empire in the north immediately collapsed. Although it was fairly rapidly restored they did have to fight another 20 years to make sure that Northumbria became a part of the kingdom of the English.

His reign left a template for a kingdom of all the English including the regal styles and the titles. He pretty much establishes that up to the Humber, Northumbria will be a part of the English kingdom. A lot of his ideas will prove useful to the future including his lawmaking, a coinage for the whole realm and even extending Alfred’s translation programme. Æthelstan was really ambitious and saw himself as a late Carolingian king.

It is a premature kingdom of all the English but it is there and later generations always saw him as the first king even though he possibly overreached himself in many ways. His model was probably [Saint] Bede’s “gens Anglorum”: the English people. These can include Mercians, West Saxons, people of Danish descent, Cornish, Welsh people and speakers on the English side of Offa’s Dyke. It is a nation, as one 10th Century source says, of many different languages, customs, costumes and so on. In a sense, it’s a visionary kingdom based on Bede’s blueprint that Alfred then dreamed up and Æthelstan brought into being.

Æthelstan and Anglo-Saxon history in general are both extremely important for English history but are they relatively neglected subjects because they are often viewed through the prism of 1066?

I think so. People forget that the English state was really a creation from before 1066. English law, language and literature was before 1066 and there were many, many important things that were established in the Anglo-Saxon period. If you look at the whole period from the Roman departure in 410, its 1,600 years and 650 of those are Anglo-Saxon so it’s a massive period in terms of roots. In terms of the creation of an English state and laws in the 10th Century it is also really important. Æthelstan’s great assemblies are now thought to be the origins of the English parliament with consultations of the regions and localities so it’s massively influential.

We do view it through 1066 and we count our kings from then and not earlier and that’s an interesting thing. We get people like William of Malmesbury who was writing in the 1130s and whose parents were English and Norman. He talks about the common opinion of Æthelstan among ordinary people in the street in the 1130s and their view was that there was nobody more learned or just that had ever ruled the state. So they still had a very strong sense of these people not as a semi-mythic warrior king for example but as an actual administrator, law-giver and personality because they were much nearer to them.

Michael Wood has produced a number of books and documentaries on Anglo-Saxon England. For more on early Medieval warfare, subscribe to History of War for as little as £26.