Historian and author Andrew Wiest discusses how the Guard has changed over the centuries and how it has adapted to 21st century warfare

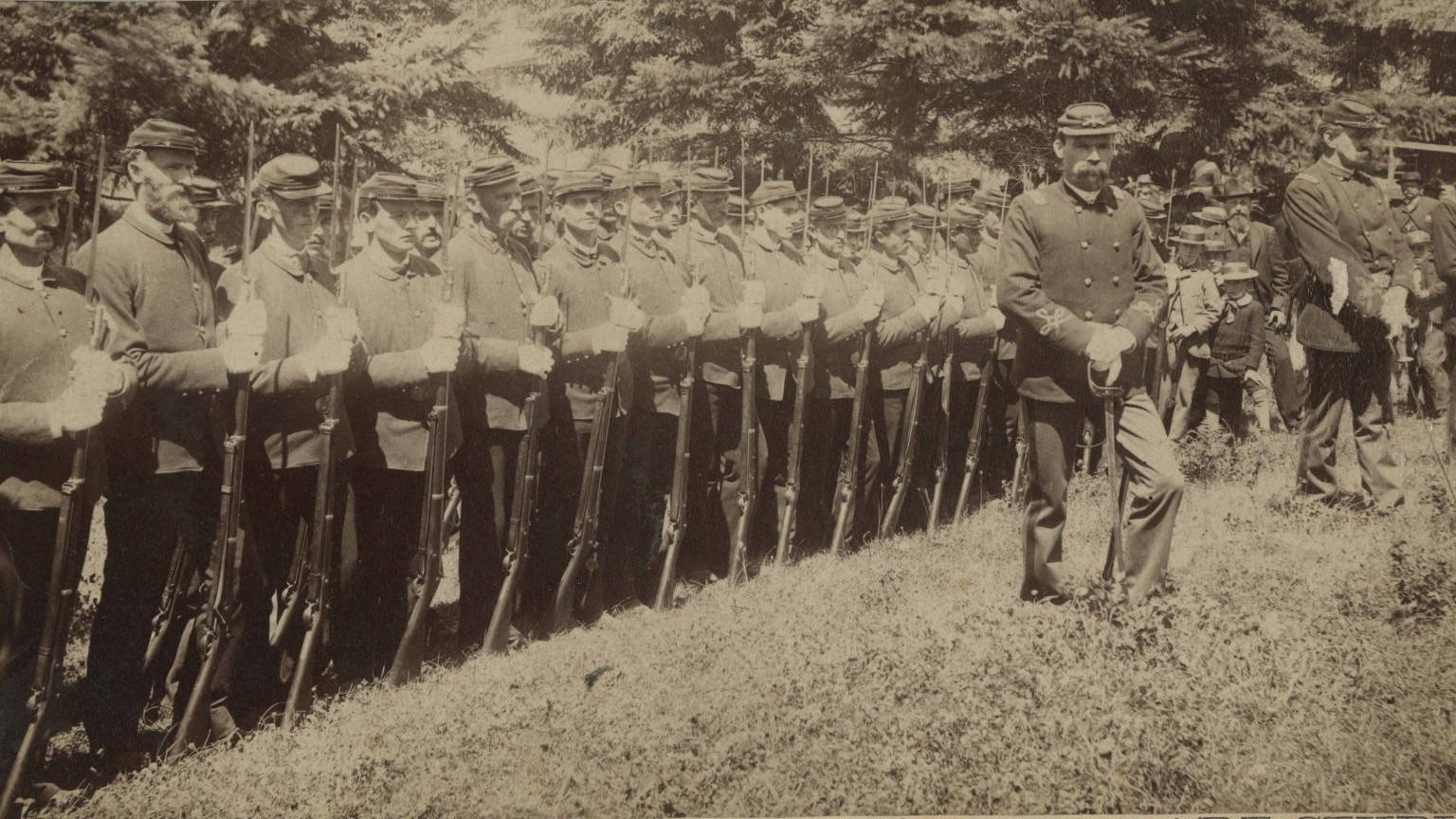

Featured image: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing

Andrew Wiest’s latest book Dogwood, published by Osprey, traces the experience of the 150th Combat Engineers of the Mississippi National Guard in their 2005 tour of duty in Iraq, centred on the forward operating base Dogwood. The unit comprised of youths hoping to attain a way out of grinding poverty, women seeking to break barriers, and patriots answering their nation’s call after 9/11.

Here, Wiest discusses the history of the US National Guard, how it has changed over the centuries and how it adapted to 21st century warfare.

When was the US National Guard founded?

The National Guard dates back to the very earliest traditions of the English militia system, specifically the Elizabethan train bands that were transplanted to the New World, beginning at Jamestown but solidified especially in Massachusetts. The Regular Army dates back only to the Continental Army of the American Revolution.

What was the relationship between the National Guard and the Regular Army, and how has this changed over the centuries?

The National Guard functioned both as state militias and as the chief reserve force of the Regular Army. Initially the relationship between the two was rather haphazard, but as the US took on a greater role on the world stage the National Guard had to become more regularised to play a heavier role on the battlefield, leaning much further into its role as a reserve force.

Photo: DPLA / public domain

How and why was the Guard more closely integrated into the Regular Army in the late 20th century?

As the Regular Army dwindled in size the National Guard had to be integrated in as a kinetic force more than ever before. Especially with the demise of the draft after Vietnam, the military shifted to a ‘Total Force’ policy that focused on linking the National Guard ever closer to the Regular Army as an immediately deployable military force.

Related: How a black railway porter from New York became the first American to win the Croix de Guerre

What were the major changes to the Guard after 9/11?

After 9/11 there was a surge in National Guard recruitment, with the new soldiers knowing full well that they would be deployed to war under the ‘Total Force’ policy. Training ramped up, with National Guard units making regular runs through the National Training Center. And a deep restructure took place as the US shifted from divisions to enhanced brigades as the base deployable unit of the military.

What operational roles were Guard units tasked with during the Iraq War? In particular can you describe the role of the focus of your book, the 150th Combat Engineer Battalion, in 2005 at Forward Operating Base Dogwood?

National Guard units made up essentially half of all US deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq, meaning that National Guard units were tasked with everything from logistics, to route clearance, to land ownership in a counterinsurgency fight.

Photo: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing

The unit I study, the 150th Combat Engineers from Mississippi, were supposed to go to war in 2005 as combat engineers. But necessity transformed them into an infantry battalion tasked with holding an Area of Operations in one of the hottest corners of Anbar Province. With essentially 200 combat troops, the 150th faced an Area of Operations larger than New York City that was awash with insurgents and armaments. Devising their own homespun counterinsurgency techniques that often grew out of the Guardsmen’s experience in the civilian world as police officers, farmers, construction workers. . . the 150th innovated solutions to their tactical dilemma that would presage much of the American strategy that was developed later in the conflict.

Related: The Eye of Desert Storm: Inside the Iraqi Army in the First Gulf War

How prepared were the 150th in training and equipment for the environment they were in?

The 150th had trained diligently and well for many months both in Mississippi and at the National Training Center before their deployment. However, they found themselves facing a different assignment. They had so little intelligence on their new Area of Operations that the convoy that was headed to FOB Dogwood got lost on the way there. The unit was also woefully short on up-armoured vehicles that were designed to face the IED threat that bedevilled the area.

Do you think perceptions of the National Guard as ‘weekend warriors’ have now permanently changed as a result of its performance in the 21st century?

Certainly. The ‘weekend warrior’ vision of the National Guard was essentially linked to the Vietnam War in which the Guard was never called up and was seen as a haven for those not wanting to fight. As the ‘Total Force’ policy developed – one designed to make the Guard deployable and kinetic – that old myth about the National Guard was dashed.

How do you think the Guard may change again in the near future?

The Guard began its history as the local community at war. As the role of the American military in war has changed, so has the Guard. It remains community based, but is now much more closely linked to the Regular Army, especially in terms of readiness and deployability. As the military continues to get smaller, the National Guard will have to become an ever sharper instrument of war, taking it ever further from its militia background.

Dogwood: A National Guard Unit’s War in Iraq is published by Osprey and on sale now

Pick up Issue 146 of History of War for the Andrew Wiest interview. The issue also includes a cover feature on the Luftwaffe and we ask “What if the US didn’t enter WWI?”