Paddy Ashdown is one of the most eminent politicians in Britain. As leader of the Liberal Democrats between 1988-99, he led the new party to increasing electoral success. Now as Lord Ashdown of Norton-sub-Hamdon, he continues to be a leading voice on national and world affairs. Nevertheless, before he entered politics, Ashdown was a soldier who served in both the Royal Marines and the Special Boat Service. As an officer he saw active service in Borneo and Northern Ireland among other places and even as a politician he witnessed the horrors of conflict during the Bosnian War.

Ashdown spoke to History of War about his military career, his new WWII book Game Of Spies and the warnings from history that politicians should heed.

When you are conducting research for your military books such as The Cruel Victory, A Brilliant Little Operation and Game of Spies, how much of your own military experiences influences what you are looking for and eventually write?

People always know about Paddy Ashdown the soldier but in fact it’s almost the least important part of my life because I was only in the Royal Marines for 11 years. Of course it was an important part of my life but people also tend to forget that I was in the Foreign Office and before I became a Member of Parliament I had been on the unemployment register as a youth worker.

You bring to bear all those experiences when you write a book. You do draw on your experiences and what you’ve done and you grow on the insights you provide. For instance when I was writing A Brilliant Little Operation, I vaguely knew what it was like. I’d served in the intelligence business so I know what its like to be in that area and you draw on that but it would be simply wrong to say that this is exclusive because like any writer you draw on all your life experience.

What influenced you to write your new book Game of Spies?

As I say in the book the trigger for it was a friend called Richard Woolridge, the man who runs the remarkable, and I really recommend it to your readers, Combined Services Military Museum in East Maldon. It’s extraordinary; I don’t think there’s a museum to match it anywhere in Britain when it comes to what they’ve got there.

Richard was the person who rang me up and he’d read my Cockleshell heroes book. He said, “Hi Paddy, I’ve just come across this box of documents that have been sent to me by a vicar in the Isle of Wight and which apparently came from a house that had been emptied out. The house where these documents came from was called ‘Aristede’ but the word was the codename for the agent Roger Landes. Richard said, “Are you interested?” and I said, “You bet I’m interested” and I came down and saw the box.

My colleagues and I immediately realised that what we had here was the private papers of Roger Landes. Landes and the two other characters were fleeting figures when I wrote the “Cockleshell Heroes” book but here they were on my desk again. In looking through the private papers they led me to the archives in Bordeaux and it was there that I realised that I had the capacity to write a book that was able to follow the lives of these three men as they tried to find and fight each other in Bordeaux over a period of two years. This had never been done before so therefore I could produce an intimate portrait of what it felt like to be a secret agent in southwest France as part of the Resistance over all those years. Like so many books it was really just almost a case of happenstance.

Why did you decide to join the Royal Marines in 1959?

From the age of about four my family had chosen that I would join the Royal Navy. In truth, I think I realised the Navy wasn’t quite for me. I had a naval scholarship that paid for my last years at school and at that stage, the Royal Marines came into view. I was never very good at maths and I’m not sure I could have done the maths to get into the navy.

Going to university was something I would have liked to have done, and I did indeed get a place at a university but my parents couldn’t send me there. In retrospect, the Royal Marines was exactly the right thing for young Paddy Ashdown to be doing, rather than going off to university where I would have wasted my time with doubtless too much beer and girls.

Can you describe your experiences fighting in the Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation?

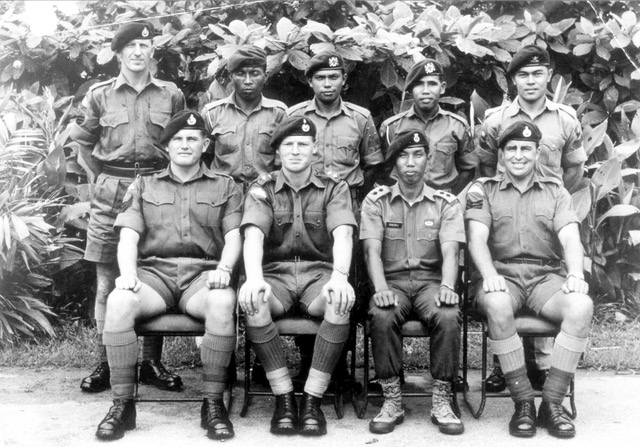

It was one of those little wars at the end of empire. I was a young officer in charge of 20 marines, in an outpost in the jungle, four hours march from the nearest headquarters being supplied by helicopter over a period of about three or four months fighting guerrillas with the then Indonesian forces.

It was quite an eye-opener and obviously you mature quite fast under those circumstances. I have to say that I learned a lot from my sergeant because he knew a lot more about warfare than I did. I had to learn from him and learn very fast but I loved it. I won the silver medal for my year at the Royal Marines and I think people respected what I did as a soldier, but that’s up to them I can’t comment.

When did you decided to join the Special Boat Service (SBS) and what did your training and duties involve?

I decided that I would try and go a bit further in the business of soldiering and applied for the Special Boat Service.

I did parachute training in the base at Poole and then in 1965 I was sent out to command 2 SBS in the Far East to train other officers. We were just reaching the end in Borneo of what we called the “Confrontation” and it involved operations and developing new techniques.

At that stage we tested a particular technique called “Goldfish” for getting out of submarines and returning to them without the submarine having to break the surface. So we were developing those techniques but also those operations that the SBS were required to carry out.

You’ve previously stated that you became a liberal during your time in the SBS. Was there a particular incident that influenced you or did you come to a natural conclusion?

You often find that after active service opinion can swing left. Some of it is because of that sense of the brotherhood of man. You rely on each other – I relied on them and they relied on me. At that stage, the men that I was privileged enough to command were by any standards better at the job we were doing than I probably was. It was an accident of birth that I was in charge of them and not the other way around. I learned a huge amount from them and I learned, and I was utterly convinced, that you could create a nation to be a meritocracy. I hate the class system and if we could create a nation in which people progress according to their ability, and the men I worked with had a high ability indeed, then this would be a better country.

I was never one for giving orders, they were given, I hope, more casually. Whenever we went on something difficult I’d come up with a plan but my team would sit around together and often improve it. So from that I learned the value and importance of the individual and the fact that you can trust individuals and that you should empower people. Judging people according to ability and the dependence you have on each other in difficult circumstances is one of the bases of liberalism.

How did it feel to be commanding a Royal Marines company in Northern Ireland, a place where you had largely grown up? Were you surprised at the level of sectarian violence?

I had been involved in peacekeeping abroad but I was brought up just outside Belfast so this was my city and it was a very wrenching, emotional experience to suddenly protect the peace. I was the son of a Catholic father and a Protestant mother and we all knew very well the Troubles were coming up, I could sense them in my bones, and so it didn’t come as a surprise.

What did come as a surprise if I’m really honest, is the fact that what I had been doing to keep the peace in Aden and Singapore was happening in Northern Ireland and my home city was being treated as a colonial hell.

We were the occupying troops, although some people tend to see this the other way around. Some of the attitudes that were around, not in the Royal Marines I should say, but elsewhere in the military there were certain colonial attitudes and I realised with a shock that they were acting as maybe I had acted in the past abroad.

At the same time the Foreign Office had approached me, and I’d spent two and a half years learning Chinese in Hong Kong. They had approached me saying we don’t have many people speaking Chinese so would you like to join us?

However, I think it was the experience of soldiering in Belfast that affected my decision [to leave the armed forces]. It wasn’t the danger, but I thought we just weren’t trying to do things as well as we could and I couldn’t influence people into a different direction. I thought the empire-based attitudes that we took in the early days such as internments were very ill advised.

How did you feel to leave the Royal Marines?

I have to say that I was very sad. I liked the Royal Marines but I decided I needed to move on and take up the position offered to me by the Foreign Office and join them.

I loved my time in the armed forces. I didn’t move on because I suddenly disliked military life because I’m still in contact with those people and I regularly attend SBS reunions and try not to miss it. I’m also very proud indeed of having been a Royal Marine and having had the extreme privilege of commanding Royal Marines on acting service.

As a liberal, to what extent, if at all, did your military career permeate your politics?

The SBS illuminated the thought and belief in me, which you would call Liberalism, and convinced me that it was the right political stance for me. Beyond that no. The thing that being in the services does give you, and perhaps it’s missing from most politicians these days, is our judgement.

The quintessential quality of a politician, the one without which they cannot do without, is moral courage. Unless you have courage then everything else, all your other talents, vanish at the moment of crisis. That’s a really important issue for me and I learnt that in the Royal Marines.

Despite your long military career did your experiences in Bosnia uncovering concentration camps (such as Omarska and Trnopolje) and then being UN High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina change your thinking about war or did it reinforce views that you already had?

Concerning the horror and tragedy – when you’re a soldier you see life on the frontline, what you don’t always see is how it affects people who are swept up in war but are not on the frontline. I famously became, amongst those who came to help me, almost impossible in refugee camps. I just couldn’t stop the tears starting in my eyes. I couldn’t prevent looking at these people and seeing my sister, wife and children so it came as a deep and profound emotional shock.

I’ve always been utterly perplexed, puzzled and bewildered by the capacity of man’s inhumanity to man and to see it face to face was a very moving experience. Nothing prepares you for going to a death camp, nothing prepares you to see the horrors of Trnopolje with all those women and children. Nothing prepares you for the fact that two or three days after you’ve left the Serbs rounded them all up and took them to the edge of a cliff and machine-gunned them. There’s no preparation for that and you never forget it all your life.

In your opinion was the British MP Andrew Mitchell right to compare Russian attacks in Syria to the Nazi bombing of Guernica?

I like Andrew Mitchell very much and I’m a big admirer, and we’re very good friends. I think there is a comparison there, yes, and I think it’s a good comparison. There are other comparisons such as Sarajevo for example but what’s happening in Aleppo is ten times worse. The difference is that in Aleppo’s case, a foreign power is acting in a way similar to the way the Germans acted in Guernica. My belief is that in the end politicians have to hold very firmly to the understanding that in the end there is only one way to stop what’s going on in Syria and that’s peace. In the end you’re going to have to sit down and negotiate with these people.

Therefore, while it’s right to identify that the way the Russians are behaving is disgraceful, I think it’s just clumsy, immature, grandstanding politics to call them war criminals like Boris Johnson (the Foreign Secretary) has done. It’s not up to politicians to call them that, its up to courts. It seems to me to suggest that he’s not really up to the job.

Its far more nuanced and to dub someone a ‘war criminal’ is a very big word. I had said to Slobodan Milosevic when I saw him about what I was experiencing the day before when I was being bombarded by the army and the defenceless villages that I saw. Now he was in my opinion a war criminal and he ended up in the Hague and indeed the next time I saw him I was at the Hague giving evidence against him. However I think calling a leader a war criminal in public is not a judgement that a politician should do. It can be done from time to time and it can have an effect but if you bandy it about you just diminish and devalue the term completely.

You once wrote about the Iraq War, “When I look to the future in Iraq, I start by studying the past.” In a similar vein, what lessons from past wars can we apply in relation to Syria today?

That’s such a good question. The bottom line is our politics is plagued today by its professionalisation. Nobody has done anything else but be a politician and I think they suffer and the nation suffers as a consequence. The other point that I think is worth making is that none of them study history. There is a saying that goes, “Those who do not know history are condemned to repeat it” and so they can’t see the historical parallels. Of course no parallel is ever perfect but it gives you a model to view the times that you’re in.

My next book is going to be about an extraordinary story that is little known about the resistance in Germany against Hitler during WWII. These were immensely brave people right at the top of Hitler’s administration who actively helped him to lose the war deliberately. They helped us to win and this is not known. So I’m reading a lot about the 1930s and I’m horrified that even though we don’t have a military madman with an army dying to go to war, although God knows what will happen with Donald Trump, but the parallels with the 1930s are really frightening. I would go so far to say that if there is one compulsory subject that I would like our leaders and our politicians to learn its history because unless you know history you have no way of judging the present.

Paddy Ashdown’s Game of Spies is available now from HarperCollins. For more insights into the causes and conduct of 20th century conflict, subscribe to History of War for as little as £26.