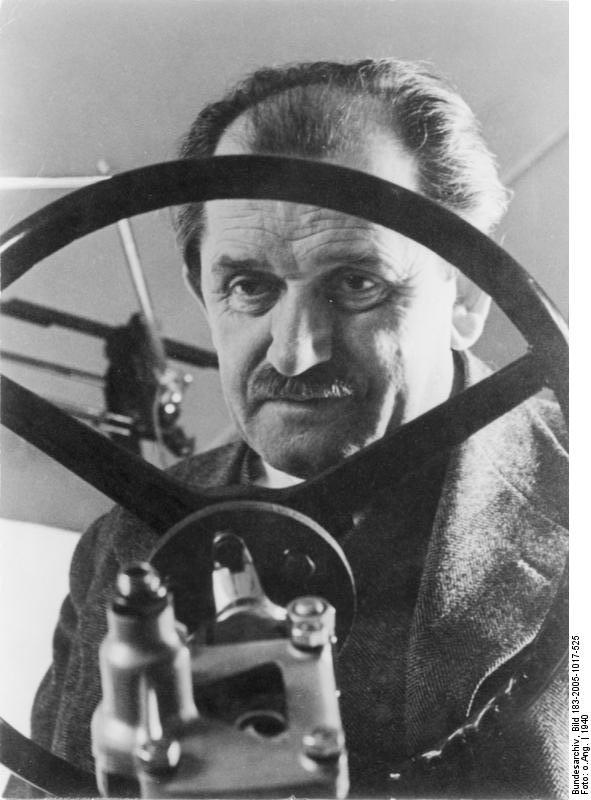

He may be one of Germany’s most famed entrepreneurial engineers – with his automotive company today making some 14,326 million Euro in revenue – but the origins of Ferdinand Porsche’s engineering legacy lies far away from the boulevards that now host his glamorous sports cars. Instead, the Czech-born stalwart has an incredible yet relatively unknown facet to the early stages of his career: building a series of vehicles for use in the German military, before eventually swapping trenches for tarmac to further exert his engineering prowess.

The son of a tinsmith, Ferdinand displayed attributes of a competent engineer from an early age, bringing electricity to his home and his family’s workshop by the age of just 13. He soon turned his fascination with electricity into a career, joining Austria’s most revered company in electrical equipment, Bela Egger and Company (the German acronym of which was VEAG). The 18-year-old Ferdinand wasted little time displaying traits of a competent engineer, progressing quickly at VEAG from a trainee to the man in charge of the test laboratories. It was here that Porsche met Ludwig Lohner, an esteemed Austrian coachbuilder of the 19th century who was keen to explore opportunities for electric vehicles.

Lohner’s willingness to examine the worth of electric vehicles sat perfectly with Porsche’s own interest in the motor vehicle and potential of wheeled power (Porsche had himself invented his own electrocycle for his commute to work) and likewise Lohner was impressed with the young Porsche’s ability to find solutions to seemingly tricky problems. For example, Porsche foresaw the switch of engines to the front of a vehicle, where they could be cooled much easier when in motion.

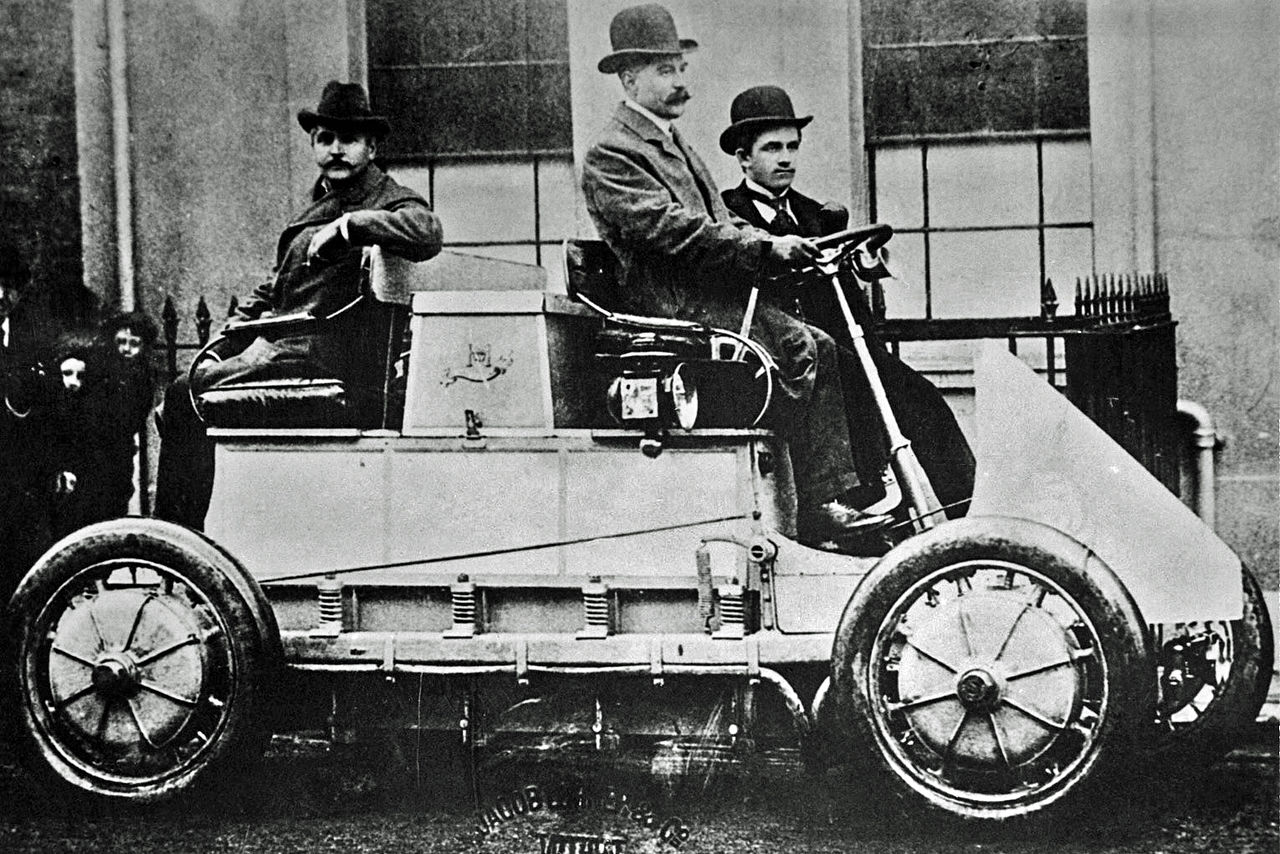

Porsche soon left VEAG and went to work for Lohner, where a variety of vehicles powered by both batteries and engine-driven dynamos were built. The clout of the electric Lohner-Porsche vehicle quickly gained momentum with Vienna’s elite, and by 1901 Ferdinand was looking at what would today be known as hybrid vehicles.

Borrowing a 5.5-litre four-cylinder internal combustion engine from auto manufacturers Daimler, Porsche made his first ‘Mixte’, a French expression to define the blend of both petrol and electric powertrains. The petrol engine of Porsche’s vehicle drove a dynamo under its front seats, which then sent electricity to its front-wheeled motors.

With a revised chassis, Porsche entered his new vehicles into hillclimb competitions, winning the large car class and setting a new record for the hill at Austria’s Exelberg hillclimb in April 1902. From here, he drove down to Sarvar to take part in Austria-Hungary’s 1902 military manoeuvres. Porsche and his vehicle impressed Franz Ferdinand, who Porsche had chauffeured, and the archduke later had one of his assistants write to Porsche to express “how satisfied His Most Serene Highness was in every respect.” Ferdinand Porsche’s move to garner interest in his vehicles from the military had worked, and it would soon spawn a 40-year career working for the armed forces.

By the outbreak of World War I, Porsche was already winning admirers with his ground-breaking designs for military vehicles. He’d designed powerful tugs with four-wheel drive for towing artillery through fields (first the 50-brake-horsepower M 06 in 1906 followed by the 80-brake-horsepower M 08 in 1910, then the ‘Hundred’ M 12 with 100 brake horsepower in 1912). These heavy-duty designs were welcomed at a time when there were rising tensions inside and outside the dual Austro-Hungarian empire.

This paid dividends: after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Bosnian militia, Porsche’s products were heavily used in the field by the empire, most notably his huge M 17 tug, which famously carried Skoda M 11 305mm mortars. Dubbed ‘Goliath’ because of its size, the M 17 weighed ten tons and had wheel diameters of 57.5 inches. The wheels were also ingeniously cleated, providing the tug with traction to give it a top speed of nine miles per hour even in muddy terrain.

Another key wartime development from Porsche was the land train. Major Ottokar Landwehr demanded a train be built that could tackle the perilous roads of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It needed to be able to negotiate sharp turns and cross dilapidated bridges, tackle ascents and descents of up to 23 per cent incline and even go back on its own tracks if needed. This was a tough job, but Porsche nevertheless took on the task.

He and his engineering partner Karl Sackward implemented big power (120 brake horsepower) from a six-cylinder engine. He also incorporated Mixte technology previously used by Porsche on cars. This ensured power was transferred, via chassis-mounted motors and electrical cables, to every alternate carriage of the train. Braking was taken care of by pneumatic hoses between trailers, and control of the carriages was adhered to by gearing that kept them on track. A steering gear and controls were also fitted to the rear of the land train, meaning the driver could switch ends and drive the train in what was effectively reverse. Later B-train developments could also be turned into rail-based train vehicles, while bigger C-trains were dubbed ‘generator’ cars, capable of shifting huge artillery.

Porsche’s Great War efforts didn’t end there. Keenly interested in aviation, it was his four-cylinder engine that found itself powering a military-commissioned airship, named the Parseval, and Austro Daimler (who Porsche now worked for) were also responsible for the designing and building of the tubular frame of the 160-foot ship’s control car. Various other Porsche four- and six-cylinder engines, with a Desaxe cylinder placement, found their way into various aircraft during World War I and beyond.

By the end of the war in 1918, Ferdinand had well and truly established himself as a leading engineer. This garnered interest from several leaders around Europe, despite Ferdinand founding his own company – Porsche – in 1931 with son Ferry.

One of those interested parties was Stalin, who wanted to significantly boost the industrial capabilities of the Soviet Union. As such, Soviet representatives visited Porsche at his Stuttgart headquarters and invited him out to visit Stalingrad, to meet the man himself. There, Stalin offered Porsche a job as general director of development of the Soviet auto industry. It was a role that Ferdinand Porsche took his time to consider, before eventually declining on the grounds that he couldn’t speak Russian.

However, it was another eventual dictator that Ferdinand Porsche would acquaint himself with, and the first meeting between the two would come in 1933.

German Chancellor Adolf Hitler promoted an interest in motor sports at the opening of the Berlin Show in 1933, and Porsche promptly wrote to him complimenting such a stance. They met shortly after, the main topic of conversation being the Auto Union’s new P Wagen. Hitler liked the designs for the P Wagen race car and sanctioned its build. The car went on to race successfully from 1934-37.

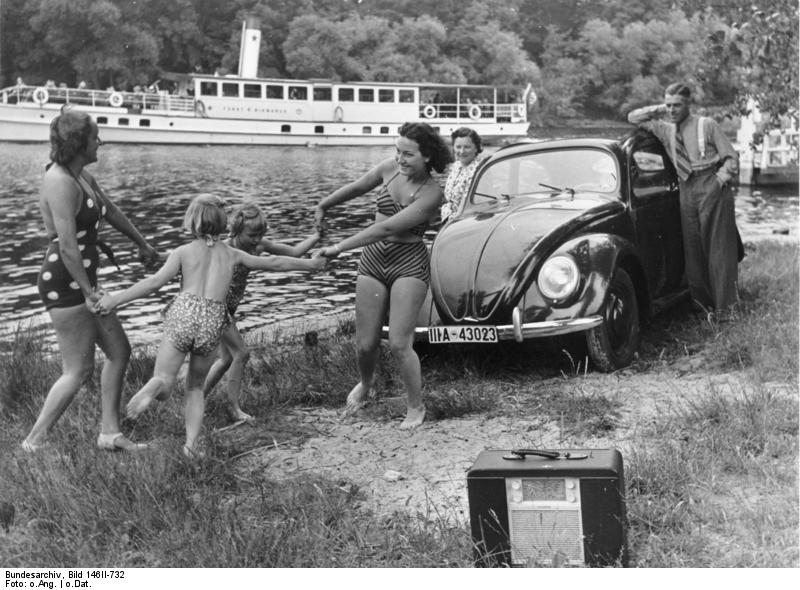

Part of Hitler’s vision for his new Germany was to build an affordable motor vehicle for the population, and he tasked the entire German automotive industry with creating it. Porsche submitted his design in 1934 and, in 1935, was awarded the contract by an impressed Hitler. In fact, the Führer was so pleased that he wanted to name the Wolfsburg factory where the car was to be built the ‘Porsche Plant’, but Ferdinand rejected the offer and the name was changed to the Volkswagen Plant (‘Volkswagen’ meaning ‘people’s car’).

Porsche’s design was simple by nature, which is exactly what Hitler wanted, as it was to be the car for the working man. The KdF-Wagen, as it was known at first – which stood for Kraft durch Freude, or ‘strength through joy’ – was available for Germans to buy by saving up stamps for it. Only a few KdF-Wagens were sold before the outbreak of World War II, when the attentions of Porsche and his engineers were needed elsewhere. The car went back into production afterwards though, when it became colloquially known as the Kaefer, or ‘Beetle’. This in turn gave birth to the automotive legend we know today.

With the ascendency of European tensions transcending into war thanks to Germany’s unprovoked attack on Poland in 1939, the huge purpose-built and Nazi Party-funded Volkswagen manufacturing plant in Wolfsburg (coined KdF City by Hitler in 1938) was quickly turned into a natural base for the building of military vehicles. Ferdinand was to be primarily based here for the Third Reich’s war effort, appointed as head of the German Tank Commission.

The workforce Porsche used to implement his designs were prisoners of war, though these were often severely malnourished and Ferdinand was known to write to Hitler asking that the prisoners be better fed. Hitler agreed to these requests until the last two years of the war, sending orders to feed those that “look like they could work hard.”

Much like in World War I, Ferdinand’s engineering nous was repeatedly called upon for military initiatives on both land and in the air. However, World War II would see Porsche excel in the water too, thanks to the invention of his famous Schwimmwagen. Essentially designed from a Beetle chassis, these amphibious vehicles were used all over Europe to patrol seized territories, and were actually meant to be part of an offensive across the Channel to Britain.

Internally named the Type 166, the Schwimmwagen (or swimming car) was borne out of the need to take machinery – and the battle – across waters in what was evidently a new maritime frontier for the German war initiative. Ferdinand received a request for an amphibious version of the all-wheel drive Type 87, and the German army specified a top speed on land of 50 miles per hour and six miles per hour in water. The transition from water to land also had to be achieved without the occupants exiting.

The Schwimmwagen took approximately three months to develop and witnessed various changes to its design in that short time. Essentially a modified version of Volkswagen’s Kübelwagen, the vehicle became doorless, while weight was trimmed and rear stowage space sacrificed to help seat four occupants.

Watertight seals were fitted to both axles and all mechanical cables, including those for the brakes. An engine-driven propeller was positioned at the rear of the vehicle after initially being housed. After much testing, the wheelbase was shortened to aid agility, particularly in getting in and out of the water, a result of increased funding of the project by the Waffen SS.

The Schwimmwagen had four-wheel drive and was propelled by a 25-brake-horsepower engine with air-cooling pipes placed well above the water line, while the exterior metalwork was treated to ‘panzergrau’ (green-grey) paint. No weaponry was mounted to the Schwimmwagen, though the vehicle’s unrivalled versatility in land and water meant it proved a valuable asset – particularly in occupied territory – to Germany in World War II.

By 1941, Hitler’s war industry and economy was in full flow. The Nazis had just emerged victorious from the initial battle of Kiev and Nazi Germany was only weeks away from declaring war on the USA. Pre-empting this, Hitler ordered a meeting to discuss development of new weaponry, with Ferdinand Porsche and tank manufacturer Henschel in attendance.

The remit for the tank was simple: Hitler needed a machine that was a step up from the current Panzers. They had to be heavily armoured to fend off attack from other tanks, capable of speeds of 40 miles per hour and equipped with a more potent cannon that was dangerous over greater ranges. Hitler wanted the 88mm cannon (originally used as an anti-aircraft weapon in 1933) to be mounted on the vehicle, and that in itself required a bigger tank, as to accommodate it meant a larger turret and a bigger, wider hull. Hitler tasked both Porsche and Henschel with developing separate prototypes in a bid to win the commission for the ‘heavy’ tank. The vehicle needed to be ready for the German army to use on battlefields by the summer of 1942.

The Henschel tank was designated the Tiger (H) and Porsche’s design the Tiger (P). Ferdinand, calling on his title as head of the German Tank Commission, assembled his prototype much more quickly than Henschel, basing his design on the previous VK3001 (P) Leopard. The tank had two air-cooled Porsche Type 101/1 engines mounted in the rear of the vehicle powering two generators, which in turn drove two electric motors that sent final power to the tracks.

However, the genius of Porsche’s radical designs on paper could not translate onto the battlefield, and numerous prototypes were dogged with problems such as breakdowns and on-board fires. The heavy 45-ton tank also struggled with its power-to-weight ratio, particularly on soft ground.

As such, Henschel and his team eventually won the contract to build the new tanks. Nearly 100 Tiger (P) tanks were already produced by then, though the majority of these stillborn Tiger Program projects were converted into tank destroyers. Armed with huge 88mm mounted gun, with 31 degrees of horizontal movement, it could wipe out an enemy tank long before Porsche’s creation itself was within range of fire. These new long-range anti-tank machines were named Type 130 ‘Ferdinands’ by Hitler himself, in recognition of Porsche’s work.

Right up until the very last days of the war, Ferdinand Porsche was hard at work, devising an improved V-1 rocket that could boast a further range and travel at speeds so fast that Britain’s anti-aircraft machinery couldn’t keep up with it. This was despite the fact that, with the updated V-1’s design remit being cheap and disposable, Porsche knew the situation for both Hitler and the Wehrmacht was by now a desperate one.

The bombing of the Porsche factory in 1944 proved the final straw for Ferdinand, who returned to Zell Am See, Austria, with his family in tow. By the time the Third Reich had fallen to its knees, Porsche was under house arrest and, on accepting an invite from the French military to visit Peugeot with a view to designing a Volkswagen for France, was promptly arrested as a war criminal instead.

It eventually took some $62,000 to secure his freedom, raised in a deal by his son Ferry Porsche and Italian racing team Cisitalia in September 1947. Ferdinand later cleared his name in a French war crimes court, though the $62,000 release bond was never refunded.

Ferry and Ferdinand turned their attentions to building sports cars in the late 1940s, with Ferry going on to craft the 356 and then, in 1963, the legendary 911 for which the company is best known. Ferdinand died in Stuttgart in 1951, aged 74.

For more on World War II machines, subscribe to History of War for as little as £26.