It could be said that posterity has been cruel to the airmen of World War I. As a society, we have an apparently bottomless well of sympathy and interest when it comes to the men in the trenches. Yet the men who fought and died in the bitter campaign three miles above them are often portrayed as comical figures in fluttering silk scarves like Blackadder’s Lord Flashheart.

Perhaps that is why, if ever we have cause to think of their war, the recurring images are those of the anthropomorphic Sopwith Camel and the Red Baron’s scarlet Fokker Triplane. Yet it is the prosaically-named S.E.5, which entered service almost exactly 100 years ago today, which was arguably the greatest fighting aircraft of 1914-18.

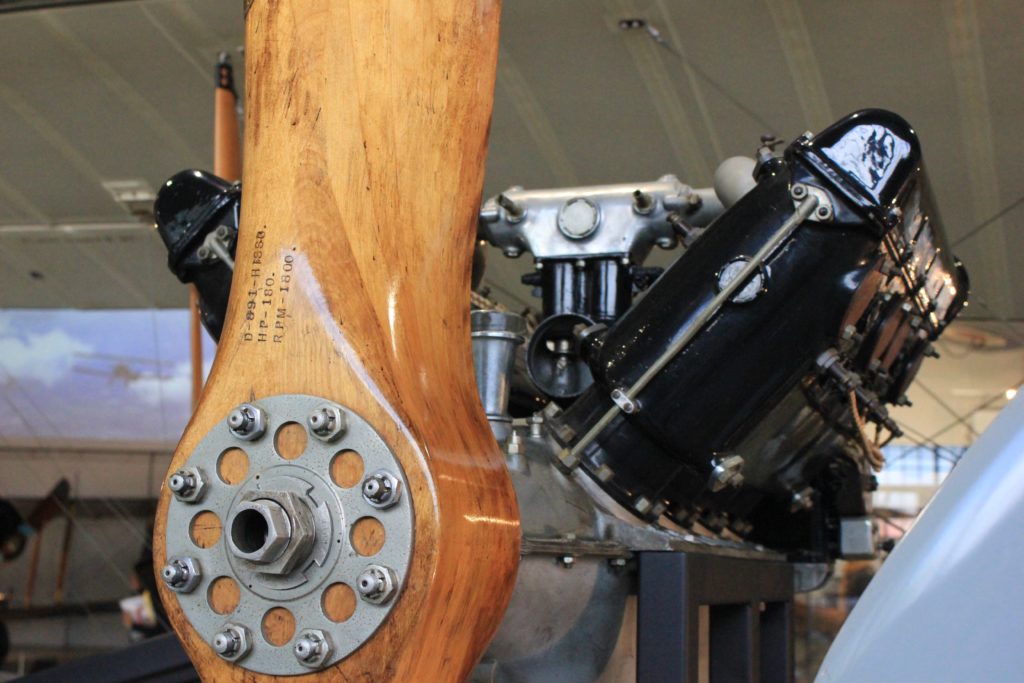

Designed around the remarkable Hispano-Suiza V8 engine, a product of pre-war motor racing genius Louis Béchereau, the S.E.5 was a conventional biplane intended to combine manoeuvrability with greater structural strength than earlier aircraft. The V8 engine carried it faster and higher than most other front-line machines while its solid construction made for a stable gun platform.

The Royal Aircraft Factory’s designers Henry Folland and John Kenworthy, together with chief test pilot Frank Goodden, worked to the premise that the war would not be won by flying rings around the enemy but instead by shooting him down. The days of gallant lone hunters jousting in the sky – and the romantic vision of the ‘cavalry of the clouds’ – were coming to an end by the time that the S.E.5 debuted above the Battle of Arras in late April 1917.

Formations of aeroplanes, as many as 50 on each side, would instead jockey for position before unleashing a blitz attack, regrouping and then attacking again. This was not a method of fighting that the swashbuckling pilots who started the war easily adapted to: most notably Britain’s celebrated hero Albert Ball, who was initially an outspoken critic of the S.E.5.

Ball helped modify the original design to its definitive S.E.5a specification, with a raft of improvements that gave the pilots better visibility, greater firepower and even a degree of warmth in the icy world of an open cockpit at 15-20,000 feet. Despite his early misgivings, Ball eventually came to rely upon the S.E.5’s rugged construction but he remained a lone hunter at heart, which ultimately led to his death in combat on 7 May 1917.

Yet despite Ball’s loss the S.E.5 went on to see more of its pilots reach the status of ‘ace’ – namely shooting down more than five enemy machines – than any other Allied aircraft in the war. The most successful S.E.5 pilot was diminutive South African pilot ‘Proccy’ Beauchamp Proctor, credited with 54 victories made exclusively on the type.

In total, 215 pilots ‘made ace’ on the S.E.5 on the Western Front and in the Middle East, while the type also served with distinction in defending Londoners from the terror of large scale bombing raids. Among these men were the classically-educated Arthur Rhys Davids, the working class heroes Jimmy McCudden and ‘Mick’ Mannock, as well as India’s only ‘ace’ of the war, Indra Lal Roy.

“The S.E.5 is a very modern aeroplane in many respects,” says Rob Millinship, who has flown the last original airworthy example of the breed for 25 years as part of The Shuttleworth Collection at Old Warden in Bedfordshire. “It’s 100 years old but nothing about it would surprise or disconcert a pilot used to modern high-performance designs.”

Pilots flying the Sopwith Camel accounted for more enemy aircraft destroyed than their counterparts in the S.E.5 but their successes came at an almost insatiable cost to their own lives. Unlike the S.E.5 with its long, stable V8 engine, the rotary-engined Camel was designed to be unstable in flight – perfect for dogfighting at close quarters but dreadful for inexperienced or wounded pilots trying to land safely.

Losses among Camel pilots stood at 831 dead (with 424 being killed in action and 407 killed in flying accidents), with 324 more pilots wounded or made prisoners of war. Among the S.E.5 squadrons, 286 pilots were killed of whom 207 were lost in action and 79 in accidents, with 170 more wounded or POW.

This means that while the Camels scored 3,318 victories in air combat to the S.E.5’s 2,704 the cost was infinitely greater. In statistical terms, one Camel pilot was lost for every four victories scored compared to one S.E.5 pilot for every six victories scored.

“Young guys with very little experience were getting thrown into these machines and it was sink or swim,” says Gene De Marco, head of The Vintage Aviator Limited in New Zealand, which has built three Hispano-Suiza powered reproduction S.E.5s under the watchful eye of proprietor and Lord of the Rings movie mogul, Sir Peter Jackson.

“If you’re a pilot with maybe ten hours of experience in total before reaching the front line, it would be very easy to kill yourself in the Camel… in the S.E.5 there were so many luxuries and so many potential problems had been engineered out of it that it was a very modern, very pleasant aeroplane to fly.”

The S.E.5 squadrons often worked in tandem with their Camel-mounted comrades. The Camel was incredibly manoeuvrable but struggled to reach more than 10,000 feet and faster than 100 mph, while the S.E.5s could get close to 20,000 feet at 120 mph. The S.E.5s would therefore attack German formations and force them down into the waiting gunsights of the Camel squadrons: each type of machine playing to its greatest strengths.

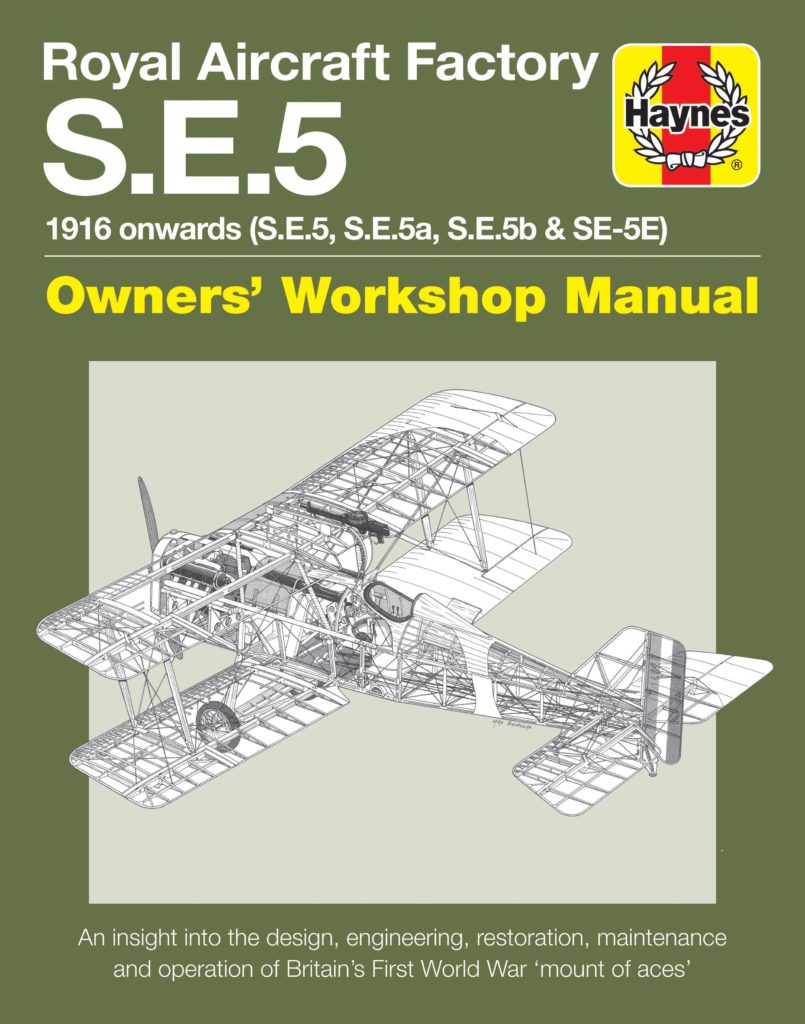

As the aviation world marks the 100th anniversary of the S.E.5’s entry into service, Haynes Publishing has released a new enthusiast’s manual for the type that details its politically-charged gestation, life in the factories where it was built and for the pilots and ground staff throughout its wartime service.

In addition, the owners, operators and pilots of surviving examples also give their insights into what has made the S.E.5 such a remarkable and enduring piece of engineering: a veteran of a war which for many of us has been obscured behind the light-hearted way in which history has often treated this grimmest and deadliest of battles during World War I.

Nick Garton is the author of The Royal Aircraft Factory SE5 Owners’ Workshop Manual, which is priced at £25.00 and available from www.haynes.co.uk. For more on the unsung triumphs of World War I, subscribe to History of War and save 25% off the cover price.