A new display at the Museum of London Docklands shines fresh light on soldiers of African and Caribbean descent who fought for the British Empire as part of the West India Regiments in the 19th century. In partnership with the University of Warwick and the Arts & Humanities Research Council, Fighting for Empire: From Slavery to Military Service in the West India Regiments focuses on the story of Private Samuel Hodge, who fought with the regiments and became the first soldier of African-Caribbean descent to receive the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest military honour.

We spoke to curator Professor David Lambert to understand the context behind Hodge’s VC valour and the difficult legacy of the West Indies Regiment in the Caribbean.

At the time of Hodge’s service, how were the West Indian Regiments viewed? The Martial Races theory emerged around the same time to put Britain’s Indian soldiers in context, but was there anything similar for men from the Caribbean?

By this time, the West India Regiments were not well known among the British public, even though they were an official part of the British army. They hadn’t been involved in a major war since that against France finally ended in 1815. Moreover, by the mid-19th century, ideas about racial hierarchy, which placed Europeans at the top and people of African descent far below them, were becoming increasingly prominent in Britain.

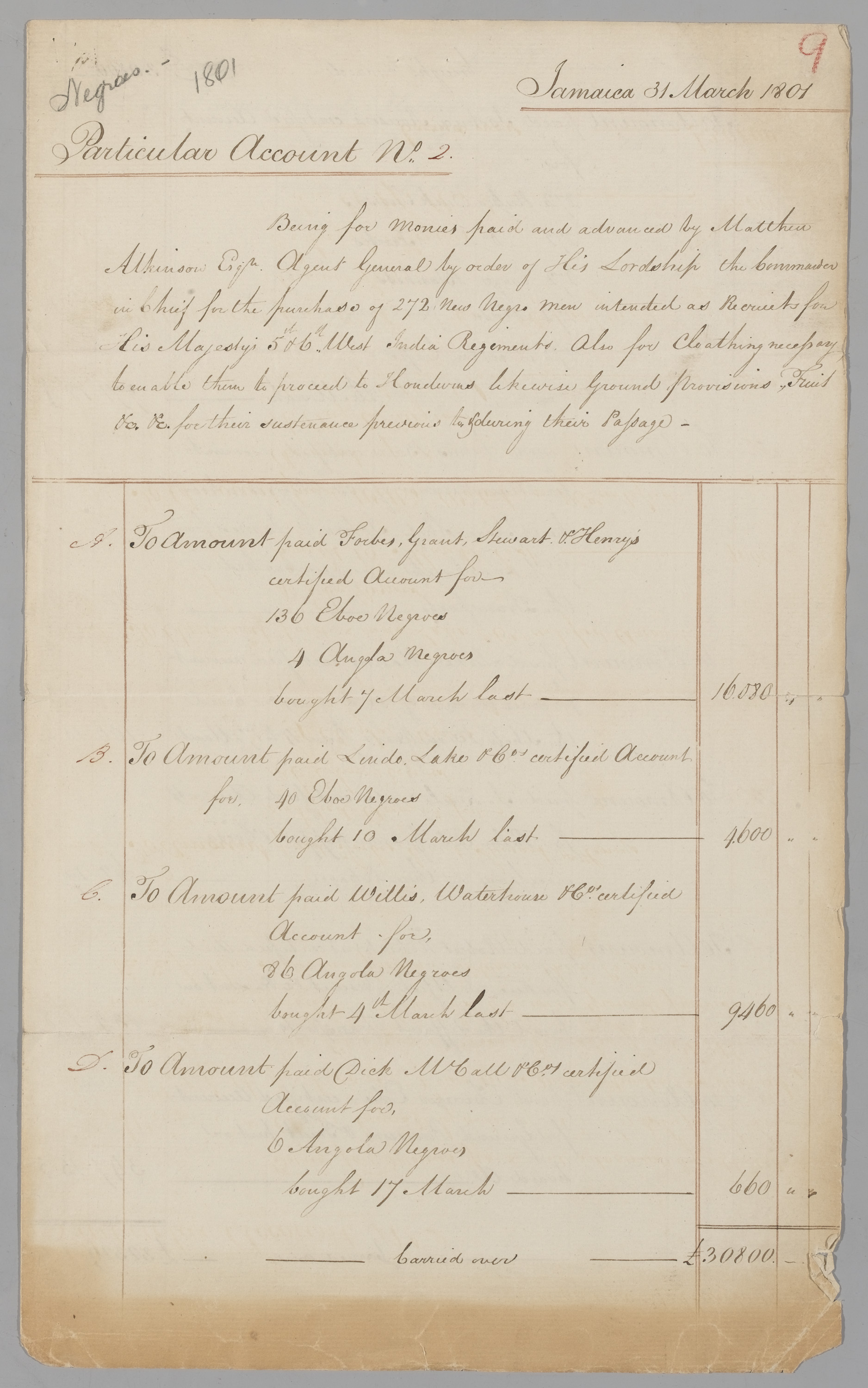

When the Regiments were first raised in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, most of the men had been bought from slave traders and the army did believe that some African ‘ethnic’ groups made better soldiers, such as those they termed the ‘Coromantee’. By the 1860s, however, the soldiers were mainly born in the Caribbean and such origins had little significance – if they ever had. Certainly, the rank-and-file of West India Regiments were not viewed like Sikh or Gurkha soldiers – or indeed the earlier equivalent of ‘martial races’ like the Scottish Highlanders. Indeed, when the West India Regiments were involved a war with the African kingdom of Asante (in modern Ghana) in 1873-74, the British officer in overall command, Sir Garnet Wolseley, was quite critical of them, believing that their some of their martial spirit had been lost as they had become more ‘Europeanised’.

What do we know of the action that earned Hodge his citation?

The action took place in the Gambia in 1866. British influence in the region was being challenged by forces associated with Marabouts (Muslim clerics). A British force of less than 400, including Samuel Hodge, travelled by river to an enemy stronghold at Tubabakolong (‘the White Man’s Well’). The force was led by Colonel George D’Arcy. After a failed bombardment, D’Arcy to decide to storm the settlement. He called for volunteers to breach the stockade, which D’Arcy led. Hodge and others came forward, and he and another pioneer, were tasked with clearing the way for the rest of the party. Most were shot down but Hodge was able to breach the defences and help D’Arcy hold off the defenders until reinforcements arrived.

This was the citation from the London Gazette, 4 January 1867:

4th West India Regiment, Private Samuel Hodge

Date of Act of Bravery, June 30th, 1866

For his bravery at the storming and capture of the stockaded town of Tubabecolong, in the kingdom of Bami, River Gambia, on the evening of the 30th of June last. Colonel D’Arcy, of the Gambia Volunteers, states that this man and another, who was afterwards killed,– pioneers in the 4th West India Regiment,– answered his call for volunteers, with axes in hand, to hew down the stockade. Colonel D’Arcy having effected an entrance, Private Hodge followed him through the town, opening with his axe two gates from the inside, which were barricaded, so allowing the supports to enter, who carried the place from east to west at the point of the bayonet. On issuing to the glacis through the west gate, Private Hodge was presented by Colonel D’Arcy to his comrades, as the bravest soldier in their regiment, a fact which they acknowledged with loud acclamations.

Was there any resistance to awarding a black soldier the Victoria Cross? To refer back to British India, it was a long time before the VC would be granted to a non-European… so what made the circumstances around Hodge different?

Not that I am aware of – though the painting in our display includes an inscription expressing regret that Hodge’s commanding officer, George D’Arcy, had not received the Victoria Cross, so you could see that as an implicit criticism. The West India Regiments were an official part of the British Army and Hodge was the second person of African descent – the first soldier and the first from the Caribbean to be awarded the VC – after the African-Canadian man, William Edward Hall, of the Royal Navy in 1857. William James Gordon, another West India Regiment soldier, was awarded the VC in 1892.

How significant was the decision to deploy the West Indian Regiments outside of America and the Caribbean?

The West India Regiments were raised in the Caribbean but small numbers of men were sent to West Africa from the 1810s as efforts were made to recruit soldiers at Sierra Leone. By the 1840s, the Regiments were rotated between service in the Caribbean and West Africa. These two regions were closely interconnected, first by the slave trade and later by efforts to end slavery. Similar arguments informed the decision to post the regiments in both places, particularly that soldiers of African descent were less vulnerable to the climate.

It’s tempting to see a certain element of distasteful symmetry in a regiment initially raised from African slaves, being used to suppress rebellion in Africa. How are Hodge and the West Indian Regiments remembered today in the Caribbean?

Great question – and something that I intend to do more research on next. The West India Regiments are commemorated in museum exhibits in Barbados and Jamaica. The Defence Forces of both those countries trace their origins to the Regiments and their bands still give public performances wearing the traditional ‘Zouave’ dress. They have also appeared on commemorative stamps, including one issued in 2000 in the British Virgin Islands that features Samuel Hodge.

Yet, the reputation of the West India Regiments in the Caribbean is also quite controversial because of the role they played in helping to suppress revolts by enslaved people in Barbados in 1816 and by free people in Jamaica in 1865. Both events have huge importance today in their respective countries and for some in the Caribbean, the soldiers of the West India Regiments were dupes at best, traitors at worst.

What is the positive you think visitors should take away from Fighting for Empire?

People of African and African-Caribbean people have a long history of service in the British armed forces, dating back to more than a century before the First World War, and this should be better known. That hundreds of men were recruited for the West India Regiments in the late 18th and early 19th centuries demonstrates the importance of the Caribbean region – and of sugar and slavery – to Britain and its empire at this time. Yet their role in not only fighting French soldiers, but also in helping to put down resistance to British rule from enslaved people and African-Caribbean civilians, as well as helping to defend and expand British rule in West Africa, gives a great opportunity for reflection. When we remember the history of the West India Regiments, we should think how this might look different from a British, Caribbean or African perspective.

You can see Fighting for Empire: From Slavery to Military Service in the West India Regiments at the Museum of London Docklands, 10 November 2017 – 9 September 2018. Entry is free to all. For more on the British Army in the 19th century, subscribe to History of War for as little as £26.