Saragarhi: The True Story reveals, for the first time on film, the fate of the 21 Sikh soldiers of the 36th (Sikh) Regiment of Bengal Infantry who on 12th September 1897 found themselves surrounded by 10,000 Pathan tribesmen during an uprising on the North West Frontier between colonial India and Afghanistan (now located in Pakistan). These 21 Sikhs valiantly held out against the odds for nearly seven hours before being overwhelmed. News of their bravery travelled the world and is still commemorated in the form of Saragahri Day. The documentary tells the story with unique access to private archives, never-before-seen images, stunning visual graphics effects and re-enactment scenes, stripping away some of the mythology to expose the truth.

With the 120th anniversary of the Battle of Saragarhi falling so close to the 70th anniversary of Indian Partition, it’s interesting how the legacy of this imperial adventure cuts now across so many religious, ethnic and state lines. Journalist and filmmaker Jay Singh-Sohal – author of Saragarhi: The Forgotten Battle and director of the Sikhs at War project – explains why this story captivated him, how this incredible film came together and how 120 years on its message is able to cut through the conflict and controversy of Britain’s troubled history with the Indian subcontinent.

I think the first thing that really struck me about it is you’re clearly having a lot of fun. You got to play with the Martini-Henry rifle, you got to do all the BBC Four stuff, you got to handle some artefacts, you got to look at an oil painting. Were you consciously trying to use those tools about something that you were particularly passionate?

Absolutely, the passion hopefully came through, but it was very much looking at taking a story, which for most people is just a headline, it’s just a top headline, and it’s just some details here and there, and through the seven and a half years of research I’ve done, with delving into the story and getting primary sources, images, trying to bring it alive really, so that people could feel that they could be connected to it. And things such as demonstrating the Martini-Henry, the signalling equipment that they used, the heliograph, was very much about showing, there was a reason why these soldiers found themselves in Saragarhi. And the reason was because of their soldiering, which is a very practical element, we thought it was a skill in itself.

And to say that actually, this is something that hopefully with that sort of hands-on encounter, people can get more of an insight into, but also not feel that this is a history that’s disconnected from them, that there is a connection to it. So, in terms of the rifle for example, marksmanship principles: when we talk about how you handle a rifle, what’s the best way of making that shot count, if you like. It would have very much been the skillset then, as is now, but it shows that these soldiers had a command over their equipment and there was a technique behind it.

And I was quite conscious that yes, for me it’s fine, great, I got to fire it, but we want to bring the history alive, away from being just text or a headline somewhere and actually give it some sort of a presence, a persona. So it was all very much about bringing it alive and how do we do that. And how do we demonstrate and take the journey to show why it’s still significant.

It also felt very contemporary in the sense that, an isolated fortress, holding out against ridiculous odds with only limited communication and support, is also a story that’s coming to us more recently through isolated compounds in Iraq and Afghanistan. Was the way that frontier wars were being fought in the Empire the start of a modern way of war, or is it just a way we fight now feels very Victorian?

I think with the frontier you do see some extraordinary acts and regiments doing some extraordinary things, because by and large they were always outnumbered, and they were coming up against a formidable enemy who, who whether it be jihad or Holy War, was being galvanised towards a certain end. And you had these defenders there, you had these defenders at Malakand, where Churchill served, you had these defenders at Saragarhi on the Samana with the 36th Sikh Regiment being there. It was a period of time when Britain was effectively holding on and maintaining control over these areas with limited resources. It couldn’t send thousands upon thousands of men, of Indians effectively, to do that job.

But also the realisation that they weren’t there to fight, defend, and be heroic, even though this happened at Saragarhi. So, it was very much effectively a tripwire during the Great Game, for if the Russians, which was a big fear of the British, were to come through, or if there was a Pathan uprising and they would come through, it was very much a tripwire to hold them back, whilst the rest of British forces could be mustered. Whether it would be at Hangu or Kohat, the garrison towns, or further back into the Punjab heartland. So they were never meant to be there en masse, on horse, but what we do get is a sense of the remarkable nature in which a small group of men, of Indians, in this instance the 36th Sikhs, were able to effect an outcome despite their number being so low, against an overwhelming foe.

And then relating it to the other part of your question, to today, I think it’s a reflection of the fact that soldiers, or men in uniform, do extraordinary things. And certainly we see that within British history, we see that within Britain within the current context with the conflicts that we’ve seen. Extraordinary professionalism, and absolutely heroic in terms of not being just one man with a rifle but, through their skill, through their abilities and capabilities, just being far greater than the sum of their parts. So it’s extraordinary, and I feel quite proud as a British Sikh being able to pore back and reflect upon being both a Brit and a Sikh.

And the fact that they did it, and they did it because they had that utmost belief in what they were doing and their duty. So I think that’s where we can take that inspiration from the frontier. And that never say die attitude, which we have in the British forces, to say actually, when you’re committed to a cause you do stand above and beyond your enemy.

I was very struck in the documentary by the image of the young British Sikh soldiers posing for a selfie by the First World War Sikh memorial. History is this kind of contentious, constantly evolving thing, but for Sikhs in the British Army it’s actually comparatively neat. Although the relationship has changed between 1897 and 2017, broadly there were Sikhs in British service then and there are Sikhs in British service now and it bypasses a lot of the conflict. It’s interesting that the Saraghari anniversary comes so close to the anniversary of Partition because I think it does reveal how many lines these events cross.

I had a couple of minutes to spare earlier, so I ended up reading some threads about Saraghari on defense.pk, and it was really interesting because there’s very clear lines of thought on display from just the Pakistani perspective. On the religious end,there are people that are saying, in religious terms, this was an attack on our Muslim brothers, so why are we celebrating this battle? Then a more sober voice is going, the modern Pakistani army is descended from the British Indian army, so this is a part of our heritage too. And then there’s the more nationalist line of well, this was an imperial venture and we shouldn’t be celebrating it . And it makes it quite difficult to make your way through that landscape. So obviously when making the film you were going to India and you were talking to people there…

I think it’s very difficult sometimes to navigate through the landscape in terms of people’s sentiments, and thoughts and beliefs, when there are so many difficulties with talking about British Empire, let alone frontier history. I came at it from the point of view of where I stand as a third generation British Sikh, so with my upbringing in Birmingham and with my reading and belief, which was very much of the shared history and the shared values that Britain and Sikhs have, and coming from that starting point. And I think it was natural for me to do that, because it was the only way I could really tell the story from my position and that point of view. But with an understanding of how people might relate to it differently.

So for example on the religious issue, yes, Saragarhi and frontier war wasn’t about a fight of Sikhs against Muslims, it was about the frontier. And it’s interesting in Saragarhi that you find that these Pathan tribesmen who’d been incited to wage jihad by the Mullah of Swat, even after the battle they came by [the site] and they told the stories of the Saragarhi defence, and the Samana defence, and it was an honour for most of them to say we came across this bravery, and obviously for them they felt that they’d beaten [the defenders]. But it was almost, a brave story should stand on its own two feet. So the religious element doesn’t come into it, that’s more of a modern thing.

But I think it can be difficult with how you relate it to a modern, contemporary audience. In the UK of course people will have different perspectives and views on it, in India you get that as well. But I think we take away from the history what most appeals to us. So you can take away the fact that the 36th Sikhs then went on to fight during the First World War, Second World War, and had a remarkable and glorious history there, for our freedoms. And has since survived in its descendant regiment, the 4th Sikh, which is an Indian Army regiment. So it’s very much about finding the themes as well, with what will resonate with target audience or the people that you’re trying to talk to. And if that happens to be an Indian audience then we can look at this shared heritage once more, but being conscious and cognizant of the difficulties.

If it’s a British audience, which is my primary focus, it’s about inspiring young people to undertake acts of public service. The constant comment that comes up from primary records about the bravery of the Saragarhi 21, was this devotion to duty. Devotion to duty always comes up. It’s on the memorials as well, that they showed this remarkable devotion to duty. What does that mean? Did they do it because they fought for, the Queen, and the Queen-Empress was on their mind before, or did they do it because they were soldiers and that’s the oath that they had taken? It’s of course the latter, and it happened to be the case that they were one of the martial races of the British Empire, and they had the pride in being Sikh and martial. And Sikhs have a very rich, strong martial tradition as well.

So a lot of elements come into this. But I think sometimes, there’s no right answer in history, sometimes we have to have an open conversation and say actually, what does it mean to us personally, in order to navigate through it and find some kind of resonance or meaning to it.

It’s very interesting because Saragarhi comes between between the 1857 Mutiny and 1914 in which the Indian Army becomes this incredible force, incredibly high esprit de corps. So fantastically organised, there’s respect between the Anglo officer class and the men, and it’s all really carefully integrated. And after the experience of the First World War that begins to fall apart a little bit, and by the Second World War, nationalism started to come into play. Did the way in which Saragarhi is remembered and Saragarhi Day is honoured, did that change as a result of the First World War do you think?

So the key then to after the First World War was Jallianwala Bagh massacre 1919, so that was the atrocity in Amritsar [in which the British Indian Army murders over 379 protesters, mostly SIkhs]. But we forget that a lot of these regiments were still abroad, they weren’t in the Indian heartland. We think of the Great War finishing in 1918, which it indeed did on the Western Front, but it continued on to 1919, the Third Afghan War, Indian troops were still in Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq, they were still in Persia, they were still in parts of East Africa. They were in Trans-Caspia, in parts of modern day Russia and the bordering areas of Russia. So Indian troops were very much still active beyond the 1918 period, and were abroad.

So it’s hard to gauge whether the atrocity that took place in India resonated, or not resonated. But we can say that, look, in terms of recruitment numbers, in terms of the numbers of regiments and then the subsequent action in the Second World War, it didn’t really make much of an impact. Because people were still willing to serve, and they had their own reasons for serving. But what you did see though, was more of a consciousness about the fact that soldiers were fighting for Britain, and yet Britain was treating Indians in a bad way.

But it didn’t stop Sikhs, or Indians generally, fighting during the Second World War, or serving during the Second World War, albeit with a view that they were fighting for their own independence as well. So it’s a difficult one to gauge, but I think the key thing about Saragarhi, taking place when it did, in 1897, was it was that benchmark really, it was that turning point in terms of the British and the attitude towards the Sikhs.

The Sikhs were during the First World War sent to every arena, every theatre of the war, and some theatres that we don’t even remember or recall or have much information about, so Qingdao in China for example. They were there fighting Germans, they were in Trans-Caspia, fighting the Bolsheviks there, later on in the war as well. As well as on the Western Front. So there is an immense contribution there, and Saragarhi was very much a turning point.

And the British reaction, the response to it, to recognise Saragarhi and the way Saragarhi could inspire many more people was phenomenal. I think it was almost unprecedented. The building of memorial gurdwaras, places of worship connected to the regiment, one in the heartland of Sikhdom in Amritsar near the Golden Temple, specifically so that people would remember this act, is a very powerful message that the British wanted to send.

And that’s before we start thinking about the Indian Order of Merit, the de facto version of the Victoria Cross as the highest medal of gallantry that could be awarded to Indian soldiers, the IOM, was given to 21 Sikhs at Saragarhi, and also 34 other Sikhs that were at Gulistan, the fort. 56 medals being given out in one action is remarkable. Imagine 21 men being given the Victoria Cross for one action, you’d hear all about it.

It was a similar response at the time by the British. It was heliographed, it was morse code light flashed from the frontier, and made its way to relay stations, and was being telegrammed back to London. The Times reported on it within days of it happening, and within days after that it was reported worldwide, it was unprecedented that this sort of action could take place. The British certainly recognised it as such.

Do you think that the emphasis, and the role of the warrior ideal with the Sikh community, has inoculated Saragarhi from those debates, to a certain extent, about nationalism and about imperialism? Has it left it ring-fenced a little bit?

I think yes and no, but I think Saragarhi was always maintained as a military story, and preserved by military types because it very much speaks to a military mindset. I think if you try to use it for different means, it becomes very difficult, and I think when people try doing that it’s obvious what they’re doing. Because this was a military action, this was an action by men in uniform fighting for what they believed in, for a cause, because that’s what was in their DNA, that’s what was in their blood as a martial race.

So every so often in Bollywood or elsewhere we see people try to make a quick buck on it or try to do a polo match, or try to use for other purposes, but you can see through it. As a story it talks about the bravery and the valour of the 21. How do you remember that, how do you hold it up? You do so by actually just telling the story as factually as you can, and allowing people to take that story away and leave with a feeling that they were inspired by it, or moved by it, or taken some sense of understanding away for what it means for them.

And I think on the Indian side, the fact that the British created a battle honour day, and the Indians have maintained it within the 4th Sikh Regiment has been a great thing, because it means every 12 September they can honour that regiment’s past and the heroic deeds of the regiments and the members of the regiments. And it’s something that we’ve wanted to bring back, and that we’ve now brought back to the UK with the fifth annual Saragarhi Day taking place with Her Majesty’s Armed Forces this year at the National Memorial Arboretum.

And in maintaining it on its battle honour day, we can remember the past, we can narrate those heroics, but we can also really just take a moment from our busy lives to have a bit of a sense and understanding of what drives men to do what they did at Saragarhi?

It definitely feels as though over the Great War centenary years there’s been a long overdue focus on the experiences of South Asian soldiers, there’s been a lot of exhibitions and documentaries and things like that, that are surfacing these perspectives. Is that something that you’ve benefited from as well?

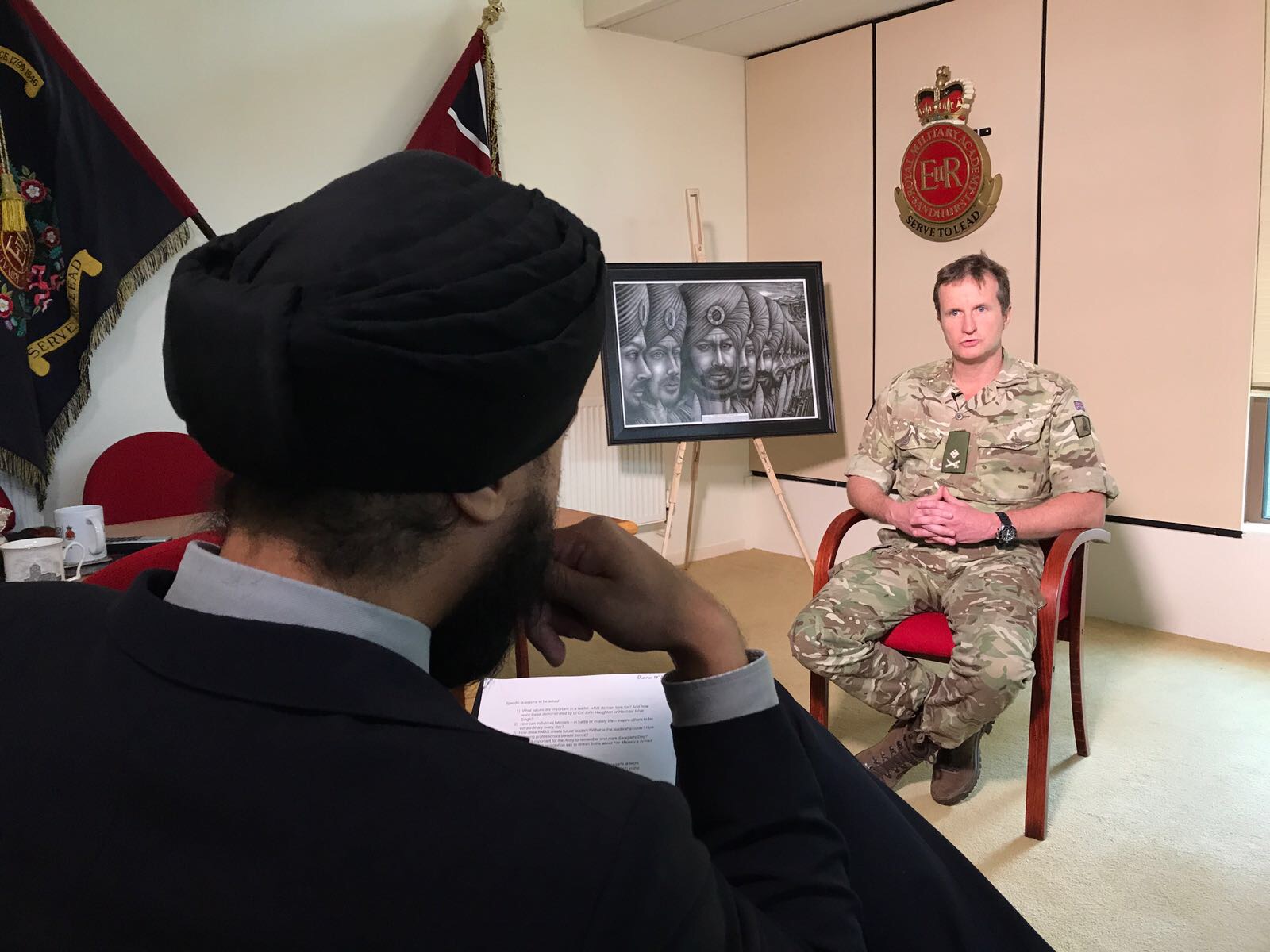

I think they come hand in hand. So Saragarhi, my book which I wrote, was launched at Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst in 2013, and then with a bit of conversations with leaders within the army, we were able to say let’s maintain this and do it annually on the 12 September. And that was what, five years ago, so we’re in the fifth year this year. I think the Great War’s been great for storytelling in the sense that people want to feel a connection to this past history. It’s not just about white, Christian men from England that fought. And I think that through the work of various organisations, community groups bringing these stories out, but also a recognition that there was a contribution from far and wide, that we’ve been able to bring those stories out.

Saragarhi’s always been there, the background of the story, but it was always harder to delve into in the UK because of independence, because it became an Indian thing. And so what 2013 did, it basically gave the British Army a way of saying, actually we still have a sense of owning this. And if I may say so, it’s because of the work I did with bringing it forward to say to them and have a conversation with the army about how we can still do it. I don’t think it would have ever been done by a non-Indian, if you like, taking that story forward, because how do you know it resonates with the community? How do you know about what we’re talking about, what we’ll say, actually won’t offend anyone?

And this is the great thing about the next generation of young people who are getting more engaged about this history and are being inspired by it. They’re finding unique ways of telling the story. I’m a journalist and I’ve made a film, but as we look down the line we’re seeing the use of technology, where you’re seeing a lot more creative ways, plays for example, that help tell these type of stories. Artwork as well. And it’s important, because it allows a younger generation to actually explore the story for themselves and try making some sense of it. And themselves being able to highlight and talk about it.

I think the film that you’ve made and your various projects they do offer a way of doing that that doesn’t get exclusionary.

I’ve always aimed at the fact that these stories need to be told in a mainstream setting to as many people as possible, because it’s an inspirational tale, because it can actually motivate people to not just research this history or take pride and want to know more in this history, but also to shape their own livelihoods and their own viewpoints about where we are today as British Indians.

So I think it’s a generational thing. Getting the story to as many people in the mainstream as possible has always been quite key. And we can only do that if we start exploring how creatively we can tell that story in the types of environment and forms where people will gravitate towards it.

Was it a story that you were exposed to at a very young age?

I heard about it over a period of time, but it was only when I started asking questions myself, and trying to delve into it and trying to find out more, I was never happy with the answers. So literally do that Google search, literally looking at Wikipedia, and thinking, that doesn’t really answer my question. And then noticing that there were quite a lot of inconsistencies and inaccuracies as well. And the infamous one is, one account of the battle says it received a round of applause in parliament. As a politics student, I knew that Victorian England, and certainly to this day, applause in parliament doesn’t happen.

So those sorts of things made me wonder, why all of a sudden have these things become canon when it comes to this story, to use a Star Wars phrase? I was never satisfied with it, and the more I began to read, the more I started to go to the libraries and looking at primary sources, the more my fascination developed. So that was where I came from with it, with this desire for wanting to know more.

And it’s happening again, not with Saragarhi but with another battle, which interestingly enough, within my research there was a report of a battle within Somaliland, and it wasn’t 21 Sikhs, it was 40 Sikhs. And the reason why, I came across this with the Viceroy of India mentioning it as, “another gallant act in 1902.” And I want to hold myself back from it because I know what will happen: the more I start looking into, it the more I’ll want to write about it and delve into it and research.

But it’s that sort of quest and thirst for knowledge I think has been my journey with Saragarhi, and it’s the thing that I really hope inspires many more people to follow their interests, and really have that desire to want to know more about their history, wherever it may be, and to explore wherever it might take them, and that meaning, that sense of what it stands for.

Saraghari: The True Story will be screened on Tuesday 12th September 2017 at the official ‘Saragarhi Day’ commemoration hosted by Her Majesty’s Armed Forces which this year will be held at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire. The film will be broadcast on KTV (Sky channel 858) at 9.30pm on the same day. Find out more at dothyphen.co.uk/sikhsatwar/