Brest-Litovsk

Britain was horrified when the news broke from the east: Russia would play no further part in World War I and the Eastern Front would now be closed under the Brest-Litovsk Treaty. All the British military material in Russia was now under threat of being taken into the hands of the new communist government or even the Germans themselves. Britain, France, Japan and the USA all agreed, something had to be done.

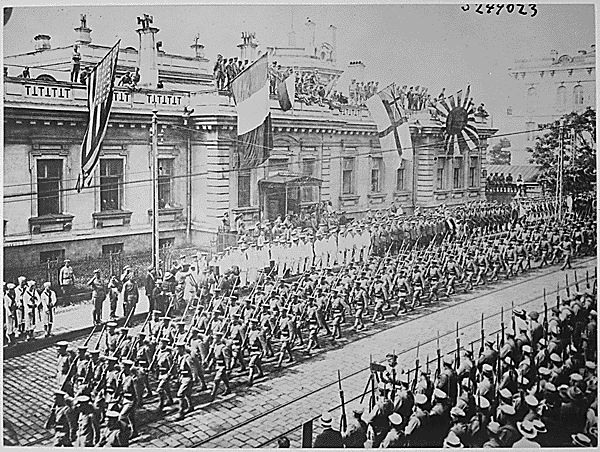

Go east, young man

Shortly after the treaty, the British began assembling troops in Russia. 30,000 men were sent to the Arctic ports of Murmansk and Archangel while another similar size force was stationed in Caucasus in the south. This area was made into a Socialist Revolutionary Government, but the men who were sent were by no means frontline troops. Only posted in Russia as they were unfit for service against Germany, the British soldiers were not much use and their orders were to keep open the Trans-Siberian Railway rather than directly serve the White Army generals. Of much more use were the funds Britain sent to Russia – £100 million-worth of equipment, in fact. This aid was crucial in the Whites lasting so long in the war.

An example that demonstrated Britain’s reluctance to participate in full force came in early 1919. Alexander Kolchak, an ex-admiral in the Imperial Russian Navy and White supporter, went on the offensive and took the city of Perm. His forces now stood at the banks of the Volga, within distance of Moscow. The British were meant to help form a two-pronged assault from Archangel, but backed down as the advance came to nothing. This would be the White’s best chance to defeat the reds.

Half-hearted intervention

As World War I finally ground to a halt in November 1918, the White Army generals were hopeful that Britain could divert more of its forces to helping their fast-becoming-critical cause in Russia. However, this was not the case. Britain was weary of war and was becoming tired with the corrupt and anti-Semitic stance of the majority of the Whites. There was now no need for an Eastern Front and soldiers were needed back home to help in the post-war rebuilding project, not fighting wars in the east. Besides, a divided Russia was a weak Russia and it would be beneficial for Britain for the Reds and Whites to continue fighting among themselves. The Whites didn’t help themselves either. When reports surfaced of their armies committing atrocities on innocent civilians, the British, along with the other interventionists, sought to distance themselves from the cause to save international face.

Red Victory

The intervention in the Russian Civil War was never a cohesive attempt. The British in particular supported the Whites over the Reds but didn’t warm to the White leaders, who they saw as a lesser evil. The main motivation was to get Russia back in the war; it didn’t matter if Russia was led by Lenin or Kornilov, the manpower was required against the Central Powers. Luckily, for the remaining members of the Entente, the German war effort broke down as the German Empire collapsed and war was won. After the Great War ended, Liberal David Lloyd George, along with Socialist French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau and Democrat US President Woodrow Wilson, was particularly reluctant to wade into the conflict, but Conservative Winston Churchill was keen to stem the Red tide. German imperial ambitions were no longer a threat in the east and the only motivation now was political: destroy Communism in Russia before it could even begin. However, severely weakened after the war, Britain, Japan and the USA did not take any further action and the Soviet Union was born.

It took time for all the men to return home from Russia. The USA, for instance, was still recording losses late on in the civil war as 174 men died in Vladivostok in 1919. By the autumn of that year, all of the allied intervention had ceased. Overall, British involvement in the Russian Civil War was a half-hearted attempt to first save the war and then subdue the rise of Lenin. The assistance given to the Whites can be seen as increasing anti-Western sentiment in the new USSR. The likes of Stalin and Gorbachev played on this image of standing up to bullies of the West throughout the 20th century and the Cold War.

For more on 20th-century warfare, pick up the new issue of History of War here or subscribe now and save 25% on the cover price.

Reference:

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/firstworldwar/spotlights/allies.htm

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwone/eastern_front_01.shtml

http://econfaculty.gmu.edu/bcaplan/museum/muchado.htm

http://www.britannica.com/event/Russian-Civil-War

http://www.criticalenquiry.org/history/polarbear.shtml

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/modern-world-history-1918-to-1980/russia-1900-to-1939/the-russian-civil-war/