Alison Kay is the Archivist at the National Railway Museum, York. She led much of the research behind the museum’s ground-breaking new First World War exhibition, Ambulance Trains, which opened on 7 July 2016. Find out more at nrm.org.uk/ambulance trains.

The British Expeditionary Force had rail logistics right at the heart of its operation – were ambulance trains already part of this elaborate plan or did they evolve during the war?

Ambulance trains were part of the British Government’s war planning before the First World War broke out. As part of the Government’s secret preparations for an anticipated Europe-wide war, the managers of Britain’s railways were gathered to form the Railway Executive Committee in 1912. This Committee was designed to run the railways during such a conflict, and drew up plans for 12 ambulance trains to be used in Britain, ready for the mass casualties of war on a European scale. These secret drawings were sent out to railway companies across the country, so when war was finally declared on 4 August 1914 the railway industry was ready.

However, ambulance trains also evolved during the war. Initially British railway companies supplied ambulance trains for use in Britain only, picking up injured men from ships and transporting them to hospital. At first French railway companies were to provide overseas ambulance trains for use in France, but with the country experiencing heavy casualties and serious losses in rolling stock it quickly became clear that it simply could not supply adequate transport for both French and British casualties overseas. In December 1914, the British Railway Executive Committee was ordered to build Continental Ambulance Trains to be used in France to the same high standard as the home trains.

As the war progressed so did ambulance train design, and each train was better than the last. By 1918, the railway companies had built 20 ambulance trains for use in Britain, and 31 for the Continent.

Where did ambulance trains fit into the overall landscape of frontline medicine? What was their role?

Ambulance trains were a crucial part of the medical evacuation process during the First World War, and carried millions of sick and injured soldiers to safety. The swift evacuation of soldiers to Britain would not have been possible without these trains, which were a crucial part of the long and complex chain of casualty evacuation. As explored in our new exhibition, the story of ambulance trains is generally one of survival: the trains carried relatively stable patients, who had been triaged before they were transported, to the next stage of their treatment. Patients were triaged before they were transported. ‘Moribund’ patients (men who were likely to die) were not loaded on board. If a First World War soldier was treated in hospital overseas or in Britain it is very likely that he would have travelled on an ambulance train.

Ambulance trains were used at various stages of medical evacuation from the front line to hospitals. They transported men away from battle as early as advanced dressing stations. Light railways were used to transport soldiers to casualty clearing stations (CCS), which were deliberately built on railway lines for the movement of soldiers and medical supplies. Ambulance trains were then used again to move men from the CCS to base hospitals, and from the base hospitals to evacuation ports. Once the men had arrived in Britain by ship, they were loaded onto the home ambulance trains that took them to hospital. Visitors can follow these journeys from start to finish in our new exhibition.

Who was responsible for them? Was the division of responsibility between the Royal Army Medical Corps and the relevant branches of the army (and perhaps even the French army and railways) a source of difficulty?

Operation was the responsibility of the RAMC, and an RAMC Major was in charge of each train.

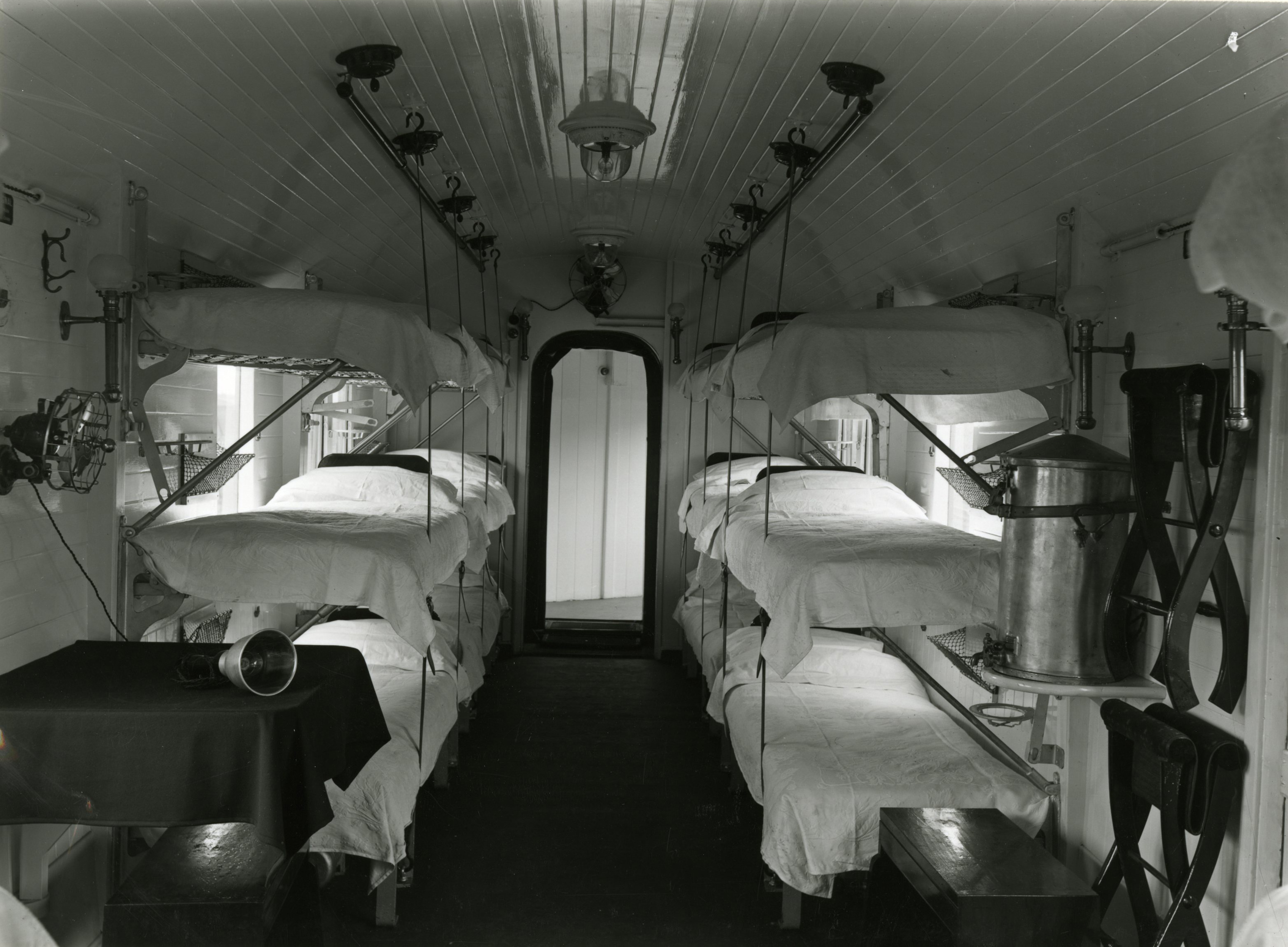

Some trains were adapted to meet the different needs of various military organisations. Naval ambulance trains, for example, were built to slightly different specifications: they had ‘cots’ rather than bunks so that the men could be transferred straight from the ship to the train without transfer to a stretcher.

From the plans available on the NRM site, the scale of facilities on board is staggering. What sort of care was available to the injured passengers?

Ambulance trains carried relatively stable patients to the next stage of their treatment. Advanced medical procedures were not attempted on ambulance trains unless there was an emergency.

Our research suggests First World War soldiers had varied attitudes to ambulance trains. Most soldiers were pleased to be moving away from the battlefields and closer to safety – a bed, food and basic medical attention were luxuries after the horror of the front. But for men with serious physical and psychological wounds, travelling on an ambulance train was an experience to be endured rather than enjoyed. They took the time to reflect on what they had been through, and the unknown future to come. For some injured soldiers, travelling on an ambulance train could be an uncomfortable or even painful experience. The small bunks were claustrophobic, and men with broken bones felt every jolt of the train. Although in general patients were medically stabilised before being loaded onto the trains, after some major battles passengers may have had little treatment before getting on board, due to how over-stretched the on-board staff were.

With so many passengers, staff struggled to give each patient the attention they needed, but this story was not reflected in the UK. Official railway company and government photographs featured multiple nurses, when in there were relatively few expert medical staff on board compared to the number of men. Generally around three nurses and three medical officers (doctors) tended to over 500 men, and sometimes many hundreds more.

Medical Officers checked each soldier onto the train and decided their treatment, while nurses gave patients skilled medical care. Orderlies fetched water, changed dressings, fed the passengers, and cleaned the train. The medical staff had to deal with new types of illnesses brought on by modern warfare tactics – for instance, fans were installed in the carriages to deal with gassing cases. In addition, nobody had expected so many men to suffer from the psychological effects of war. With little knowledge of how best to treat them, secure compartments and padded cells were added to ambulance trains.

What were the conditions like for the medical personnel on board?

Working on an ambulance train was difficult, dirty and dangerous. Staff regularly worked through the night to make sure their patients were given adequate care, and ran the constant risk of catching lice or infectious diseases, and of being bombed. During very busy times staff would often stay awake for 24 hours straight, and work in terribly overcrowded trains. Wounded men regularly filled the staff quarters due to the busy, congested wards, and trains sometimes fell off the tracks because they were so overloaded with wounded men. Kate Evelyn Luard, a nurse on an ambulance train in France, wrote in a letter to her family: ‘Imagine a hospital as big as King’s College Hospital all packed into a train … No outside person can realise the difficulties except those who try to work it.’

For medical staff faced with horrific sights and a heavy workload, time between journeys became precious. They used it to bring some normality and light-hearted relief back into their lives. Between journeys staff sometimes waited for days or even weeks for their next load of patients. This free time was a chance to unwind, socialise and explore new and exciting places. During working times after their long days were over, ambulance train staff returned to their on board living quarters for some much-needed rest and relaxation. Living conditions on board could be quite pleasant when the trains were not carrying injured passengers.

From our research we know that some staff lived on ambulance trains for many years. Staff living quarters incorporated ‘mess rooms’ where they could socialise, and we have even found stories of some nurses personalising their living quarters by making curtains. Staff had their own baths and showers, and ambulance trains were usually heated throughout. For those on the best trains, accommodation included steam heating and baths. Others were less fortunate, and had to live with freezing temperatures and basic conditions.

What role did ambulance trains play in the Somme and what challenges were faced as a result of that catastrophic first day?

Ambulance trains were under a huge amount of pressure during the Battle of the Somme. In the first four days of the conflict (1-4 July), ambulance trains made 63 journeys and 33,392 men were moved from rail heads to bases on the coast of France. The busiest day of ambulance train traffic from Southampton was on 7 July 1916 when 6,174 men were received into the port.

Ambulance trains carried many more patients than their intended capacity during the Somme because of the sheer number of casualties. For example, Train Number 29, built by the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway, was authorised to carry 370 patients but carried 761 on 2 July alone. Temporary ambulance trains were also used to help move the huge number of wounded soldiers.

Ambulance/Hospital trains were used in many late 19th century conflicts – what was unique about their use in World War I?

Before the First World War, ambulance trains had never been used on such a large, industrial scale, although they had been used previously in the Crimean War, the American Civil War and the Boer War. The plans used in the First World War were used again in the Second World War.

Rail networks were constantly threatened in the first few years of World War I – and doggedly defended – did ambulance trains find themselves under fire, cut off or forced to a halt by the changing frontline?

Ambulance trains were targets of enemy fire during the First World War, and our research has uncovered stories of staff and patients hiding underneath their trains when they were targeted. One nurse reported every single window being blown out of her 16 carriage train during a raid. Despite the dangers of ambulance train life, nursing positions were highly sought after and attracted many applicants. Nurses were attracted to being in the thick of the action, with ambulance trains taking them ten miles of the front line fighting.

Ambulance Trains at the National Railway Museum features some of the photographs taken by young train orderly George Owen Willis during his service. He was aged 18 when the First World War broke out and was working as a clerk in the Health Department in Bournemouth. He immediately joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and served for the entire duration of the conflict as an orderly on Ambulance Train Number 18. Owen stayed on board his train until the end of the war, living in his staff quarters in one of the carriages. Train Number 18 often took shelter in railway tunnels to avoid being bombed by the Zeppelins that were flying over Britain. Owen’s office was once hit by a large, sharp piece of shrapnel during a raid – had he been in the room at the time, he would have been killed.

How did the exhibition come together and what challenges were there in presenting this incredible – arguably underappreciated – story of World War I?

One of the primary challenges was the lack of information about this forgotten story. Our exhibition is the culmination of many years of museum research. We delved into our own archives for original technical information, finding engineering drawings and plans showing how British railway companies adapted trains and carriages to essentially become hospitals on wheels. As well as this technical detail, we wanted to uncover the personal stories of those involved, and visited many other archives to find out more including the National Archives, the Wellcome Museum, the Imperial War Museum, the Army Services Medical Museum and Leeds University.

We have also made contact with descendants of ambulance train medical staff and passengers to learn their untold stories from the photographs, letters and diaries they left behind, and have worked with First World War experts who have advised us. Another real challenge has been selecting the particular aspects of our research to include in the exhibition itself. To enable people to explore the story in more depth, we also have a special programme of expert talks at the National Railway Museum running between 29 September – 1 October 2016.

It is very gratifying to finally open our exhibition and commemorate the heroic efforts of ambulance train medical staff to evacuate wounded soldiers from the battlefields of the First World War and care for them on board. After years of hard work and careful research, we are pleased to finally bring these stories which have been lying dormant for almost a century back into the public eye and give these trains and their passengers the twenty-first century prominence they deserve.

The Ambulance Trains exhibition is open now at the National Railway Museum, York. Find out more at nrm.org.uk/ambulance trains. For more on World War I picked up the new issue of History of War or subscribe now and save 25% off the cover price.