The Imperial War Museum (IWM) was established in 1917 to reflect and record WWI, which at that time was an ongoing conflict. One hundred years later the IWM is marking its centenary by exploring evolving global issues, particularly the devastating conflict in Syria, as part of its ‘Conflict Now’ strand of exhibitions and events.

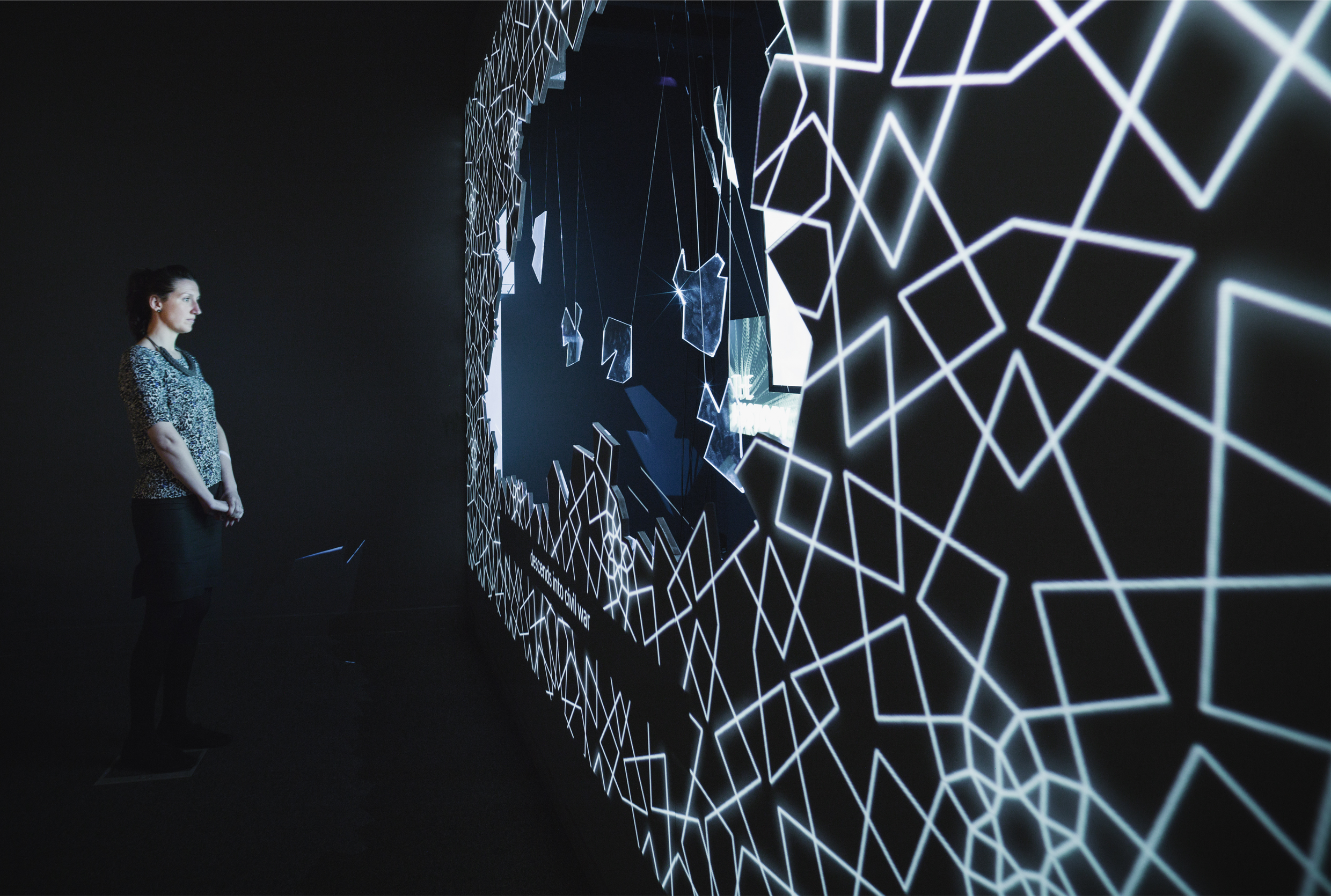

‘Conflict Now’ features the opinions of individuals who have seen, experienced and worked in areas of conflict, which include artists, photographers, refugees, war correspondents and citizen journalists. Running from 27 April-3 September 2017 at IWM London, “Syria: A Conflict Explored” will feature two exhibitions called “Syria: Story of a Conflict” and “Sergey Ponomarev: A Lens on Syria.”

The Syrian Civil War, which began in 2011 has now lasted longer than WWII, killed almost half a million people and forced nearly 11 million-half the pre-war population-to flee their homes. This is not just a domestic tragedy but also a severe global problem. Syria has been turned into a battleground for wider rivalries such as non-state militants like ISIS or great powers fighting for geopolitical supremacy like Russia and the USA. The war has also created a refugee crisis that has enveloped neighbouring countries and Europe.

Gill Webber, Executive Director of Content and Programmes, IWM explains the purpose of the exhibitions, “The situation in Syria is complex, live and evolving and we know that viewpoints may change in two years, two months, two days or two hours. We want to help our visitors cut through the complexity and enable a deeper understanding of the causes, course and consequences of what is happening in Syria today. ‘Syria: A Conflict Explored’ reflects a multitude of perspectives and positions and also questions and challenges the information we have available-right here and right now.”

The first exhibition that visitors will experience is ‘Syria: Story of a Conflict’, which is an intimate display that explores the origins, escalations and impact of the civil war. Dr Christopher Phillips is the Senior Lecturer in International Relations of the Middle East at Queen Mary, University of London and co-curator of ‘Story of a Conflict’. He spoke to History of War about how the exhibition aims to provide visitors with a broad introduction to a complex tragedy.

What was the idea for creating an exhibition based on the story of the Syrian conflict?

The idea of the exhibition was to complement the series of fantastic photographs that the IWM have by Sergey Ponomarev. The curators at the IWM felt that while the pictures are fantastic it drops the public into the deep end of the conflict without having much background knowledge. So the broad idea behind it was to give the public a relatively straightforward introduction to the conflict.

The way the media reports the Syrian conflict is in a somewhat simplified manner. They tend to reduce it to stereotypes but what I want to show is that it’s an incredibly complex civil war. It’s both a civil war with domestic actors who have their own legitimate concerns on each side but also a regional and international proxy war where different external players are using the conflict to fight out their wider struggles.

We really want the public to come away with getting a sense of that level of complexity, that they won’t reduce the conflict to a simplified explanation. Whilst they might not understand every component, the exhibition will allow them to have the tools to go on and explore and learn more.

Can you describe the different sections of the exhibition?

Its divided into three sections: objects, a film and personal stories. The centrepiece is the film, which is eight minutes long and uses graphics and archive footage to give a broad overview of the conflict. It gives an introduction about how it began, some historical background into how Assad came to power and how that helped generate resentments that were then sparked by the Arab Spring in 2011. It then goes on to explain how the opposition was fragmented and the emergence of Islamic State and Kurdish forces etc. It then finally outlines external players.

The second section, which is actually the first one when you walk in, is the objects. This is a series of objects that we’ve gathered, many from Syria or related to the conflict, and they’re selected to be symbolic of the war’s different components.

One of my personal ‘favourites’ is a street sign from a neighbourhood in Aleppo that was on the frontline of the fighting. It has battle scars and shrapnel marks. I lived in Aleppo for a year and it was quite a wealthy area. It’s symbolic of the fate of the city. Aleppo was Syria’s wealthiest city and it has now been shattered.

Finally, on the back wall we have a series of personal stories from Syrians themselves and this is very important to us. We wanted to get away from the high politics and actually give people the opportunity to hear different Syrian voices. The last thing we want to do is speak on behalf of Syrians. I hope that when people see this exhibition they will seek out Syrians where they live and get their side of the story and hear how they’ve been caught up in this conflict. We want to provide a platform and showing those personal stories is an important component of that.

To what extent is the conflict reminiscent of Cold War-era proxy wars?

It certainly has echoes but things are different. It’s important to emphasise that there is now an asymmetrical, geopolitical contest between the United States and Russia. During the Cold War there was a degree of symmetry and balance and whilst historians now know that the Soviet Union wasn’t as powerful as it was perceived at the time, it was then seen as comparable in power to the USA. Those proxy wars and showdowns in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Cuba etc were seen as part of a wider contest for global supremacy.

That is not the case in Syria-it is widely recognised that Russia is not comparable in power to the USA. What is unique about Syria is that it is one of the few states that still fall into Russia’s orbit of interest. If you look at the post- Cold War Middle East, most of the states fell in the orbit of the USA. Only Libya, Syria and Iran fell outside those areas and only Syria had a close relationship with Russia. Iran was more independent after their revolution and Gaddafi’s Libya was a pariah. Russia’s position in Syria is not a competition for regional hegemony. Rather, it is more of a defensive move to shore up its one remaining ally in the region.

Ironically, the United States looks weak for not acting in Syria and Russia looks strong for doing the reverse. Vladimir Putin has tried to leverage Russian involvement in Syria to make a claim to being more active in the Middle East but a lot of people are exaggerating the extent to which Russia is challenging the USA as an equal, especially within Syria. Much of it is due to Syria’s unique position to Russian strategic importance.

In what way is the UN Security Council particularly divided over the future of Syria and what are the geopolitical implications?

It’s interesting because the Security Council is actually behaving as it was initially designed at the end of WWII. It was this idea of four or five ‘policemen’ and veto members would get a say on what happened within their ‘spheres of influence’. During the 1990s and 2000s, that idea slipped and it ended up being the hegemony of the USA and its allies in the region. However, Russia and China are becoming bolder now and are willing to veto in areas they feel are their spheres of influence. Syria has been one of those areas where the USA, France and Britain have simply been unable to get through what they wanted. It’s not unlike what happened in Iraq in 2003 when UN intervention was prevented by France and Russia.

In many ways it’s the structural reality of the UN Security Council and by design its meant to do that. It’s just that people have not been used to it doing that and that’s way some think that the UN is not being effective. Russia (and China) have simply drawn a line in the sand and said, “We will not permit anything to go through the Security Council that risks endorsing or legalising action against our ally Bashar al-Assad” That’s the line they’ve stuck to since 2011.

What do you think is the most important part of the exhibition?

The most important aspects are the personal stories because they so often get lost. We’re trying to help educate people so that they get a broader understanding of the conflict away from these stereotypes. These are real people: they aren’t statistics. Syria was a highly developed country and incredibly well educated: one in four people of university age went to university. It was a very advanced society in that sense and has been completely shattered by this conflict. Many people now just associate Syria with refugees, poverty, conflict and desperation and its important for them to hear the real voices and to realise that this isn’t the case. I feel that is the most important component of the exhibition.

This was a country that was incredibly warm, friendly and kind to visit. Irrespective of the government, the people and culture of Syria was absolutely incredible and very much a hidden gem from a European perspective. It is now reduced to this warzone and even areas that haven’t seen fighting have been affected. Syria has been badly decimated and as someone who knows and cares for it is heartbreaking.

Syria: A Conflict Explored is on at the Imperial War Museum London until 3 September 2017. For more on the origins of 21st century conflicts, subscribe to History of War for as little as £26.