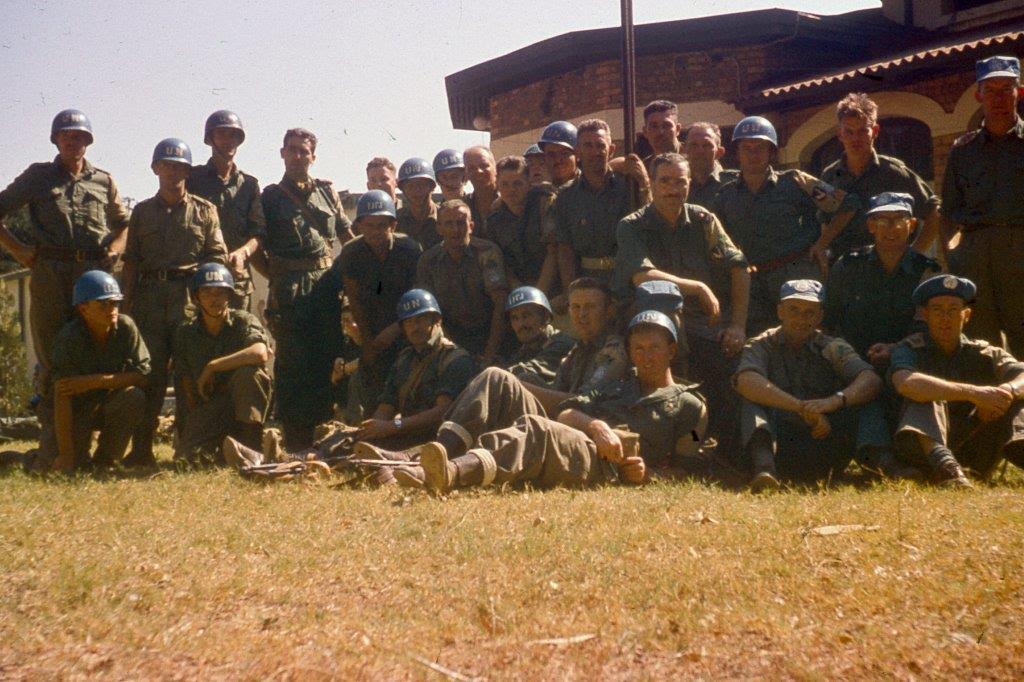

Between 13-17 September 1961,156 members of ‘A’ Company, 35th Irish Infantry Battalion were serving in the newly-independent Republic of the Congo as part of a UN mission to keep the peace in a country that was descending into civil war. Instead, the Irish peacekeepers found themselves fighting for their lives in the former Belgian colony in secessionist Katanga, which was led by Moise Tshombe. These inexperienced and underequipped troops fought a heroic defence in the prosperous mining town of Jadotville (now Likasi) for five days against 2,000-4,000 Katangan armed gendarmeries and battle-hardened European mercenaries.

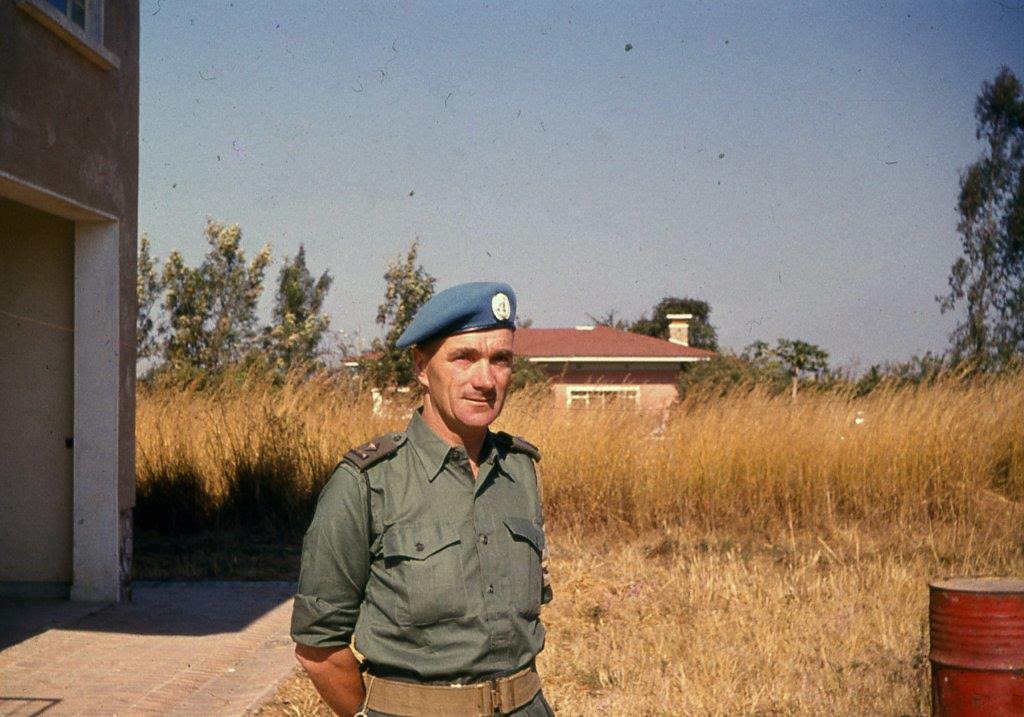

Thanks to the brilliant leadership of Commandant Patrick “Pat” Quinlan, A Company’s attackers suffered 300-400 killed and around 1,000 wounded. By contrast the Irish had remarkably suffered no fatalities and only five wounded men. However, they were inadequately supported by the UN high command and were forced into a ceasefire that turned into a tense imprisonment at the hands of their attackers.

After a gruelling captivity they returned home to a cold reception from the Irish Army and the veterans bravery went unrecognised for over 40 years. However, since the early 2000’s the siege has become recognised as one of the most wrongfully forgotten battles in Irish and UN military history and surviving veterans have now been belatedly honoured. The man primarily responsible for the late recognition of A Company’s bravery was one of Jadotville’s youngest veterans: John Gorman.

Gorman had been a 17 year-old private in 1961 but he single-handedly began and led the campaign to rehabilitate the men of Jadotville as the courageous soldiers that they truly were. Today, largely thanks to his efforts, the siege is now recognised as one of the most heroic and wrongfully forgotten stories in Irish military history.

Gorman’s campaign to hold an enquiry into the battle led to Commandant Pat Quinlan and his men being cleared of any soldierly misconduct in 2004. Since then the veterans have been steadily honoured with commemorative scrolls, a monument in Athlone in 2005 and various books and documentaries. In 2016, A Company, 35th Battalion were awarded a Presidential Unit Citation by the Irish government and the siege was dramatised by Netflix in a feature film called The Siege of Jadotville. On 21 October 2017 the first annual “Jadotville Day” will be held in Athlone in a special ceremony that will include the unveiling of a commemorative plaque. The Irish government has also stated it will award a special medal to the veterans although as of September 2017 no date for the presentation has yet been announced.

In the first of three interviews with surviving Irish UN veterans of Jadotville, Gorman spoke to History of War about his dramatic experiences during the intense siege and the subsequent campaign for justice.

TRAINING AND DEPLOYMENT TO THE CONGO

When did you join the Irish Army and what did your training consist of?

I joined the army on 22 June 1959 and went into my recruit training, which would have lasted about six months. Then you do a three-star course that makes you a fully qualified soldier and I was at home on leave when I heard about the Congo. I cancelled my leave-I didn’t say why-and went back to Athlone and volunteered for the Congo. At that time I’d say you’d have had two or three volunteer battalions because everyone was so mad to get out there! I didn’t get out there until June 1961.

What did you know of the Congo before you were deployed?

I was 17 years old at the time and knew absolutely nothing. The only thing I knew about Africa was bringing a penny into school for the babies out there and that was all, that was all I knew.

How did it feel to be fighting for the UN and what reasons were you given for your deployment?

We were not given any reasons really, just that there was trouble out there and we were going to sort it out. To a certain degree we did sort it out but I think there is as much trouble out there today as there was then.

How did it feel to be a UN peacekeeper?

I did take pride in it but we went out in really heavy Irish Army uniforms from WWII. We were issued out there with blue ‘helmets’, which were actually just the liners for the helmets and they just had ‘UN’ on them.

However, we were all young. There were 104 members of our company who were single young men out of 156 so the majority of us weren’t married. We were all just young lads and it was all really new to us in a huge way. We’d never seen anything like this before and for around 95 percent of us it would have been our first time even out of Ireland. The Yanks who flew us out there were laughing at our old uniforms and we had this little bag of food to bring out on the plane with us. I saw them loading these Jeeps and armoured trucks into the belly of the plane and I said to myself, “How in God’s name is this going to get off the ground?” But eventually we did.

UNDER SIEGE

How were the Irish troops treated by the local population?

The ordinary population out there would have been fairly ok but it was the mercenaries and their friends in the gendarmerie that were the problem. As you can imagine the mercenaries restrained the gendarmerie pretty well because they were top soldiers otherwise they wouldn’t have been out there.

There were a few operations carried out before we went to Jadotville. Operation Rum Punch was the taking over of the gendarmerie headquarters in Elisabethville (now Lubumbashi). We took that over on an August morning at 4am and our task was that we had to get in, take it over and let no word get out to the mercenaries because it was the mercenaries that we were after to capture all of them and we did. The operation went very well and we then took the airport in Elisabethville. I didn’t think that the mercenaries were going to leave but there was some dispute with Conor Cruise O’Brien (UN Representative in the Congo) about letting them go again. If they did leave they were back in action twice as quick to start what ended up being the battle at Jadotville.

Why was A Company, 35th Battalion sent to Jadotville?

“A” Company seemed to be involved in every operation that ever took place out there. Whether they thought we were the elite company or that they were trying to walk us into it I don’t know but we were involved in every single thing.

We were dug in around the airport in Elisabethville and two companies had gone into Jadotville: a Swedish company and the Irish B Company. They looked to be taken back out because of the hostility towards them so they were taken out. The Swedes got permission-they left first-and then B Company left. We actually saw some members of B Company coming out when we were on our way in and they were waving at us and we were waving back. Little did we know the trouble we were going to walk into!

But we had great men. I always say to people, “When you’re young you don’t know fear as older people would.” You couldn’t see the fear that you see through older eyes now but we had great leadership.

I must say our company commander the late Commandant Pat Quinlan was an absolutely outstanding man. We also had a company sergeant Jack Prendergast who was about six feet four, straight as die but my god was he a good soldier, he was outstanding. He was a star.

We also had great mortar men. We had a mortar sergeant who at the time would have been reckoned to be one of the best mortar men in ANY army, so much so that we were calling him “Hawkeye”! He was very, very good on the mortars, absolutely brilliant.

Everything fitted into place. I know that the NCOs were much older than us but at the same time it was their first time as well. Even to this day I have more stuff in my head thinking about how they managed and how they were able to outmanoeuvre up to 3,000 people but they did.

What preparations were there before the siege began?

We’d done all our basic training at home and then our company commander kept us on our toes all the time out there. They (Katangese gendarmeries and mercenaries) were patrolling every hour on the hour past our camp and I remember our company commander saying to us, “Just act normal as if you’re just sitting out in the sun.” We dug our trenches (although some people think was the first thing we did, it wasn’t) at night so they did not know that we had any positions dug.

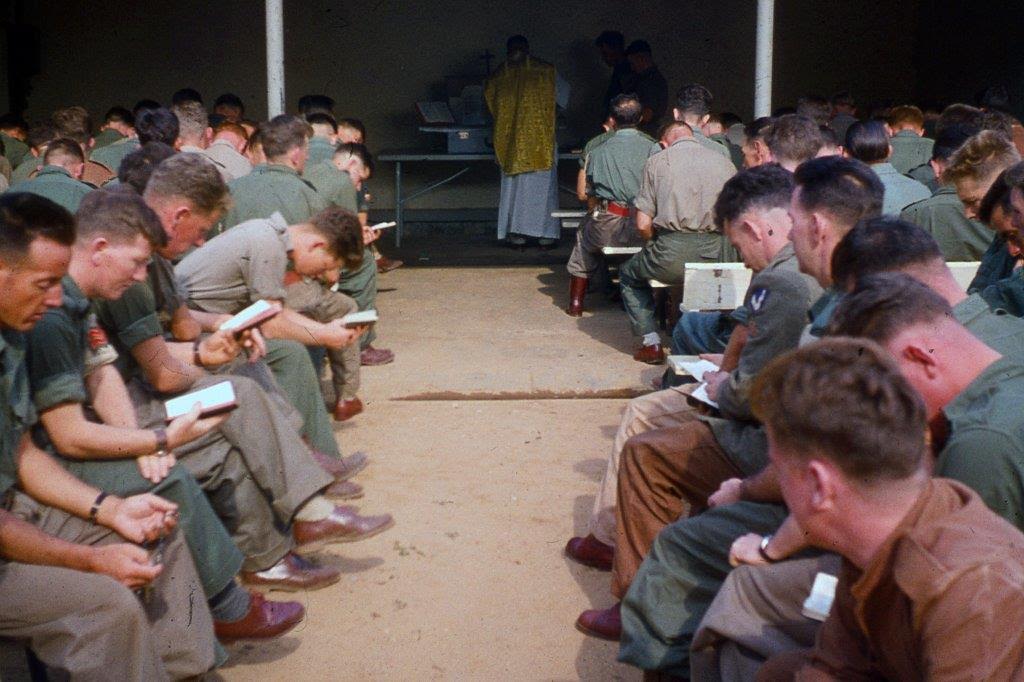

I remember we were at Mass at about 7.30 in the morning. Father Fagan was our chaplain and he was saying Mass. There were three small horse wagon trucks that came up the road and just swung into the camp as if they had nothing to do but just take it over but (Sergeant) John Monaghan wasn’t at Mass. He was in shaving and he came out with a towel around his neck after he had shaved. When he saw what was happening he jumped into the Vickers machine gun trench and he fired three or four bursts over their heads. They turned their trucks around and got out of there damn quick but then a couple of hours later all hell broke loose.

The thing was there was a garage across the road from us and the man who was running it was a mercenary. He was informing them that we were all at Mass so that’s when the trucks arrived. Our company commander put two and two together, we went over to the garage, took them out of there and we took over the garage.

You don’t know who’s who out there but he was a mercenary who was in the right place. He could tell them everything that we were doing except for the digging of the trenches because we dug them at night. I remember that when we were getting ready to go into Jadotville our quartermaster Captain Tom McGuinn looked for 81mm mortars and he was told that we wouldn’t need them. We ended up with just 60mm mortars but if we had had the 81mm we would have been ok and lot more better off.

Were you underequipped in terms of weapons?

We were underequipped and unprepared. We were going into Jadotville as part of Operation Morthor but our company commander didn’t know that he was part of Morthor-the officers were told not to tell him. He discovered five minutes before the trouble broke out that was part of Operation Morthor. Just five minutes-its not long. But we stuck it out and when we were finally released in the old airport at Elisabethville as part of a prisoner exchange we went up to our base, which was a farmyard. We were sleeping in cowsheds and all kinds of places. We were told then by General MacEoin that we’d done a great job and that we’d be well looked after but when we came home we were looked after very, very badly.

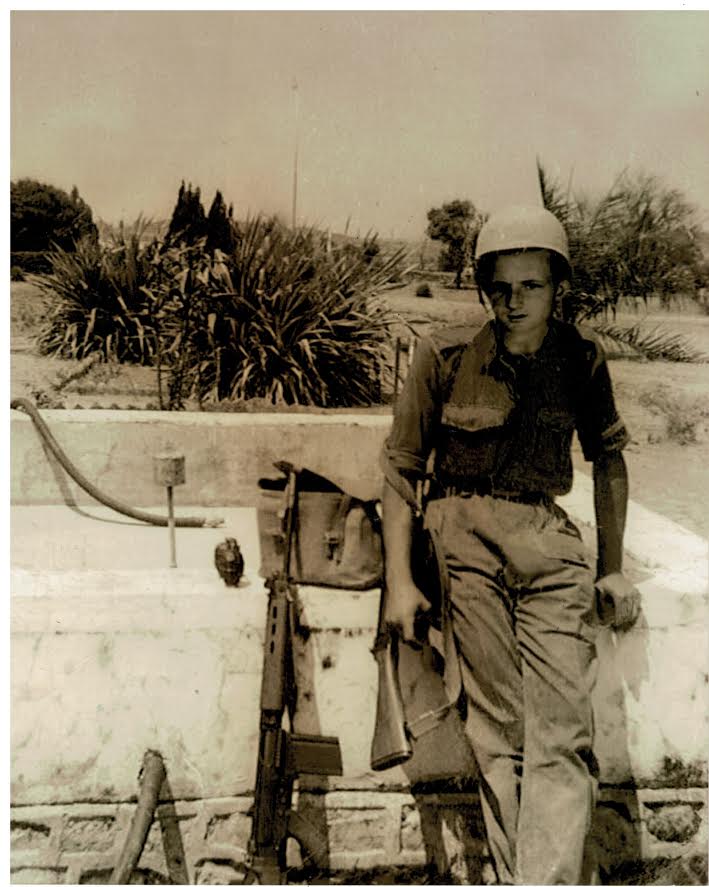

What weapons and equipment did you have at Jadotville?

We had something like a dozen FN rifles back home and we did our training on those few weapons that we had. We went to the Congo with Lee Enfield .303 rifles and issued with the FNs out there. I think they were a French rifle. That’s all we had: we had a few anti-tank guns, one or two 60mm mortars and the Bren gun-I always found that was a great weapon. At the end of it all our weapons were just ran out.

Everything we had bar the FNs were WWII equipment, its what the British would have used during the Second World War. I always found the Bren gun to be a great weapon because you could take down 20-30 men in no time. With a rifle, it was automatic but I found that the FN was better at single shots, not as an automatic weapon. I felt very confident in battle with a Bren gun.

How did your battle start?

Everyone at Mass was armed and they left our camp but about an hour or so after they attacked us. There were only 156 of us but we were so well organised and well dug in. All of the trenches were five-foot deep and some had a little step-up in them so that you could step up a bit higher. We were very well prepared for a bunch of young Irish lads that had never been out of the country before and it was just amazing. Of course we took guidance from the older people and saw that they weren’t afraid so we weren’t going to be afraid either.

Their leadership was just excellent. I couldn’t describe it any other way and I still think everyday just how they did it so successfully.

What instances of the siege stick out in your mind?

During the siege they had two Fouga jets. One was grounded by the UN in Elisabethville and the other one used to hit us every morning and then go on to Elisabethville to hit them. When he was coming back at night he would hit us as a last thing. He knew exactly where we were for the following morning but what our company commander did was that he moved us down and we spent all night digging trenches. As soon as the jet came back in the following morning he hit exactly where he had hit the evening before but we weren’t there.

How does it feel to come under jet attack?

That was frightening. The pilot was a Belgian and he was supposed to have been on loan from the Belgian Army. He was told not to bomb or fight any UN troops but he’d got bombs that were made in the Congo and he mounted two guns on the jet so that was against his orders. However, we did hit him in crossfire, which meant that he would come in at a much higher altitude-he wouldn’t come in as he did before. He knew he could be hit and he was hit.

What were conditions like in the confines of the defence perimeter before the final ceasefire on 17 September 1961?

When nightfall would come our company sergeant Jack Prendergast would come round with a bucket and spoons. He’d give you one or two spoons and I remember him saying something to me that I’d never forget, “Well young Gorman this is your first dish in a trench”, which was true. That was the way we carried on for the five days or so.

At one point they asked for a ceasefire to pick up their dead and wounded and our company commander granted that. He said that the ceasefire would be for four hours but as soon as they had their dead and wounded picked up they started firing again so they broke the ceasefire.

Finally, when they didn’t get through our first defence they looked for another ceasefire. Our company commander was wary of this and he radioed on to headquarters in Elisabethville. He was told that were ceasefire talks going on in Elisabethville and that they were going very well. It was as much to say, “Well if you don’t agree to this ceasefire and something happens here in Elisabethville you’ll be to blame.”

So he did agree and ceasefire arrangements were drawn up. They were to the effect that we would do joint patrols. We destroyed our heavy weapons such as the Bren guns and Vickers machine guns before we handed them in. We took the firing pins out and things like that and buried them.

I told you that we were going to do joint patrols but this little fellah came up with a hard hat on him called (Godefroid) Munongo (deputy leader of Katanga’s secessionist government) and he looked for our company commander. Now we were out in the open and so were their lads. They probably had our positions taken over but Munongo came looking for our company commander and met him. Whatever they said at the time I saw our company commander just pacing up and down and he was told by Munongo that he would have to surrender. That was during the ceasefire, which was against everything that the Geneva Convention ever stood for. He then broke the news to our platoon commanders and there wasn’t really anything he could do except get us all killed if he was foolish enough and we would have been killed. It wouldn’t take that long to kill 156 people.

He stood by what he’d agreed. He said, “Yes, we will surrender” but that was a laugh because it wasn’t a surrender.

What was your opinion of the Katangan gendarmeries and mercenaries fighting ability?

They should have been good because they were trained by top mercenaries. Whether they were afraid or not I don’t know but they’d wounded five of our lads and that was all. We had no fatalities, no nothing thank God and Pat Quinlan promised the families when we were going out that he would bring every man home and he did.

He was just an outstanding guy but then when I say that there were also outstanding men there as well like our company sergeant. I remember our platoon commander quite well and he was a lovely guy called Joe Leech. You wouldn’t think about it looking at him on the barracks square at Athlone but he was good. Its amazing when you think that a fellah wouldn’t be much good but by God when the chips were down he was there.

Because you were so outnumbered was there any point in which you thought you wouldn’t survive?

Our chaplain Joseph Fagan, who was actually a near neighbour of mine back home, gave us the last rites in the trenches so that was a bit scary because you’re not expected to survive etc. He was a lovely man but when you see somebody giving you the last rites in the trenches you say, “Well, this is it” but thankfully it wasn’t.

How did you feel when the final ceasefire happened?

The way I looked at it was I was a young lad and the way I still look at it today is that there was nothing more that that man (Quinlan) could have done unless he got us all killed and then he probably would have then been a ‘hero’. But there was a British brigadier general that read that book “Siege at Jadotville” and he said, “My God, if he was in our army he would be at the top rank and when he retired he would have been knighted.” That was his opinion of him.

IMPRISONMENT

What were conditions like in your captivity?

Number one, we got good food and the Red Cross came into us then and made sure we were being looked after. We were in an old hotel and then they were building a proper prison camp for us up in Kolwezi so were eventually moved up there. We were made to empty out our kitbags and a 9mm round came out of (Private) Jack Peppard’s kitbag and the guard came round and hit him with the rifle. We were unarmed of course but our company commander ran straight for him, shook the s**t out of him and said, “You don’t touch my men.” Therefore I think they were as much afraid of Quinlan armed or unarmed! They were always very wary of him.

Was there any sense that your attackers would have taken revenge on you in captivity?

We felt safe enough I suppose but during our handover they brought us down to this little village where there were only women and children. They were all shouting, wailing and crying and making signs that they were going to cut our throats and all this. It was only afterwards that we discovered that we had killed 70 percent of their husbands so that’s why they were up in arms against us.

Then they had signs on the roads from Jadotville saying, “A Company: Go Home” It was the mercenaries and the Europeans that were against us, they didn’t want us in there. The Congo at that time was separating and Moise Tshombe was taking the good parts of it. Patrice Lumumba, the Congolese prime minister who was before Tshombe had threatened to bring the Russians in so he was caught up and put in a bag and that was it. Tshombe then had the run of the place.

It was only a few years ago that I discovered that Patrice Lumumba’s family are now living in Ireland. I’m going to make it my business to contact them. All of his family play Gaelic football now and they are Irishmen! I would dearly love to meet them or at least meet one.

How many gendarmeries and mercenaries were killed during the siege and what impact did the experience have on you and your fellow veterans?

They reckon up to 400 were killed and there was up to 1,000 wounded-that’s a lot. They were all taken into barracks and trained by the mercenaries and, who knows, maybe they didn’t want to be fighting but I don’t know, no one will ever know that.

I suppose we can count ourselves as lucky, it ended up good in a lot of ways and it taught a lot of us good lessons. A lot of us left the army, including myself. I went off to England and worked in Coventry but a lot of them lads never came back to Ireland.

I’ve tracked down one particular guy-Sergeant Jimmy Rea-who was a kind of bodybuilder and taught us unarmed combat and I found him in Perth in western Australia. I found others in Spain, Canada, America and one of them I know joined the US Army and fought in Vietnam!

I found one particular chap (Private) Jackie Broderick in a mental institution in Birmingham and I was trying to make arrangements to get him home here to an institution in Ireland so we could go and see him. But I saw his brother about two weeks after and he said, “John, we buried him last week.” A lot of those people who are dead were born in 1942 and one young fellah was born in 1944-they were only kids really: schoolboys.

Would you describe Commandant Pat Quinlan as a great man?

Ah yes and he had great senior NCOs with him. I’d say it depended a lot on our company sergeant without a doubt. Jack Prendergast was a Tipperary man but he was always wary and he could read a person like a book. That’s the way he was and nothing of this man’s outlook could ever change his opinion of what he thought.

THE CAMPAIGN FOR JUSTICE

Why was there a cover-up of Jadotville when you came home and how were you treated in the subsequent years?

When we came back to Curragh military college from the Congo we were called everything under the sun and that was hard. When I retired I began to gather reports and documents to get them together to see why this was done.

Years had passed and I’d always promised myself that they can’t get away with what they’ve done so I started a campaign and everyone was telling me that, “Oh you’re mad, you’re never going to get anywhere with this” and that included a retired chief of staff who said, “You’re making a fool out of yourself. You’re never going to get anywhere with this Jadotville thing because it was so tightly covered up.” I said, “Well, maybe not but you’ll find that John Gorman will sort it out.” And I did, I did get places thank God.

That was all thanks to one government minister who was the minister of defence here in Ireland-Willie O’Dea. He phoned my house and asked me what went on in Jadotville, what went on when we came home and I told him. I said, “Is there anything more you’d like to know Minister?” and he said, “No, that’s enough.” So I went and met him in Leinster House and discussed things with him. He was shocked that this was all covered up to save “arses.” I often get asked that question, “Were we sacrificed to save four arses, two or one?” and I will answer that one day.

What is your opinion of Dr Conor Cruise O’Brien (UN Representative in the Congo in 1961) and the UN High Command?

Conor Cruise O’Brien didn’t come out of it very good at all. He deserved the treatment the film gave him but you see he was a civil servant and you never put a civil servant in a military man’s job in my opinion-he knew absolutely nothing about it. I think it was Dag Hammarskjöld who read a few things that O’Brien had written and he nominated him for the job. But Hammarskjöld was killed in a plane crash, which created more lies and his reason for going to the Congo was to see what went on in Jadotville, what happened out there and I believe to fire Conor Cruise O’Brien as well. His death created more lies.

Hammarskjöld was a good man but O’Brien later wrote a book called To Katanga and Back. He had nothing to be proud of at Jadotville and he just brushed over it slightly once, that’s all. He knew he couldn’t be proud of what had happened in Jadotville.

Do you hold Conor Cruise O’Brien primarily responsible for what happened?

Yes, and one or two more. I can’t mention who but the people in this country (Ireland) would know and they do know.

It sounds like the garrison at Jadotville was effectively betrayed by the UN High Command?

Yes, that is correct.

How does it feel to think that the UN let you down?

I did write to Kofi Anan. He was coming on a visit to Ireland so I wrote a 3-4 page letter and emailed it to him so that he would have it before he left for Ireland. I do believe that he did say in his speech to the taoiseach Bertie Ahern that, “There is some unrest among your troops, would you put it right please?”

It was a big comedown for the hierarchy here to have to bend and show that they were wrong because if they were right there was no way that we would have been getting anything. But they weren’t right, they were wrong. I have some senators working for me in the senate for a good few years and we’re now ending up getting a medal.

I actually said, “I want to see the medal before its struck and mostly I want to see what’s going to be on it.” At this point in time we’re not just going to take any old medal that would just satisfy them and not satisfy us. They’re on the run now.

What are your thoughts on the recent publicity about Jadotville?

There was a lot done before the 2016 film but I would say that the film brought it out more even though we had the monument in the barracks and the scrolls, indication and recognition etc. Nevertheless, I’d say the film played a big part in it too.

What are your thoughts on the 2016 Netflix film The Siege of Jadotville and how does it feel to be portrayed on screen?

I never gave it much thought really. I said in a local newspaper article, “It took me 73 years to get to Hollywood!”

I had a great journalist in Dublin who always said in every article, “That would make a great film” and he was right. The guy jumping out of the trench with the “f*****g snake” is me. I was played by a young actor called Ronan Raftery and the actors had to be young because we were all young.

To what extent has the film increased awareness about what happened at Jadotville?

It makes the world more aware because Netflix have bought the rights to that film and it will be shown around the world.

But you see come back many years and people laughed when they’d read articles in the papers about Jadotville but one journalist called Tom Prendeville was adamant that the story would make a great film. I had great help from Tom and local papers like the Westmeath Independent. I was also on most local radio stations around the country just before I really started to campaign because people didn’t really know about Jadotville. Nobody knew anything about it-it was as tightly covered up as you’d ever get. People would be ringing in saying, “Did you know so and so?” and I knew them all.

I worked hard and conquered it. The funny thing about it is when the monument was being unveiled in Athlone I got a phone call from a fairly senior army officer who asked me did I know who was at Jadotville? I said, “For God’s sake, of course I knew who was at Jadotville!” and he said, “Have you got any names and addresses?” I said, “I’ve got about 85 percent of them.” He said, “Oh, will you bring them in to me quick?” They should have had that stuff!

The strangely shocking thing about Jadotville is not just the siege itself but it’s also what happened afterwards

Of course. Had they done the right thing there would have been no campaign, no film, no books. There’s been about seven or eight books written during my campaign and there were a lot of television documentaries. It was really brought to the fore and I might write a book myself sometimes but if I do you can come and visit me in Mountjoy Prison!

What more needs to be done for the veterans in 2017?

The families of the deceased members worry me because they should get an apology from the government for what was done. Their fathers and brothers went to their graves branded as cowards. Surely its not too much to stand up and apologise after all of this? If I do something wrong to somebody I will go and apologise and that’s the manly thing to do. But then, is there a man in the government or in charge of the events? For want of a better word they’re dead now and they should realise that.

The Irish United Nations Veterans Assocation (IUNVA) is the association for serving and ex-service members of the Irish Defence Forces and Gardaí (Republic of Ireland Police Force). It is open to anyone from these organisations that have served at least 90 days service on a UN mission in a foreign country. The IUNVA’s primary role is to provide support and events for members and their families who have been affected by overseas service.

For more information visit: www.iunva.ie

Images courtesy of John Gorman, Leo Quinlan and Joe Relihan.