In September 1961, 156 members of ‘A’ Company, 35th Irish Infantry Battalion were serving in the Congo as part of a UN mission to keep the peace in a country that was descending into civil war. Instead, the Irish peacekeepers found themselves fighting for their lives in secessionist Katanga. Between 13-17 September 1961 these inexperienced and underequipped troops fought a heroic defence in the mining town of Jadotville against 2,000-4,000 Katangese armed gendarmeries and battle-hardened mercenaries.

Thanks to the brilliant leadership of Commandant Patrick “Pat” Quinlan, A Company’s attackers suffered 300-400 killed and around 1,000 wounded. By contrast the Irish had remarkably suffered no fatalities and only five wounded men. However, they were inadequately supported by the UN high command and were forced to surrender. After a gruelling captivity they returned home to a cold reception from the Irish Army and the veterans bravery went unrecognised for over 40 years. However, since the early 2000’s the siege has become recognised as one of the most wrongfully forgotten battles in Irish and UN military history and surviving veterans have been belatedly honoured.

10 Irish Army officers served at Jadotville with the youngest being Lieutenant Noel Carey. Born in 1936, Carey was only 25 years old in 1961 but he led 30 men in No. 3 Platoon during the siege. His courage was noticed by Pat Quinlan who later described Carey as, “a fearless officer with the qualities of leadership which are demanded in desperate situations such as this.” Quinlan officially recommended Carey for a merit award but the Irish Army medals board refused to grant any decorations to individually nominated veterans-a situation that still exists today.

However, the Irish government has recently announced that a specially commissioned ‘Jadotville Medal’ will be presented to the surviving members of A Company, 35th Battalion and to family representatives of deceased members. The ceremony is due to take place on Saturday 2 December 2017 at Custume Barracks, Athlone and the medals will be presented by the Irish Minister of Defence Paul Kehoe.

Now aged 81, Carey spoke to History of War about his experiences commanding inexperienced soldiers during a remarkable event of the Cold War.

DEPLOYMENT TO THE CONGO

When did you join the Irish Army and how did you become an officer?

I joined in 1954 as a cadet. There was quite a rigorous process that you had to go through to become a potential officer but I went to the cadet school at the military college at Curragh in November 1954. I graduated and was commissioned in 1956 and then initially posted to the equitation school in Dublin where we spent three months learning to ride horses.

I was then posted to the west of Ireland to Custume Barracks, Athlone to the 6th Infantry Battalion, which was my battalion for almost the entire of my career in the army. In 6th Battalion I was a young platoon commander and infantry training officer and subsequently became an adjutant of the battalion.

I would have known most of the NCOs and quite a sizeable number of the troops who were with us in Jadotville with A Company because I’d served with them. I’d been privileged to train some of them in support company, mortar and machine gun training and as recruits when they initially came in.

I was also hugely involved in sport. My sporting career led to internationals in soccer when I joined the army. I became a provincial rugby player playing with the team at Athlone and was involved in practically every other sport such as basketball, gymnastics and volleyball. At that time sport was particularly encouraged in the army because (although its difficult to imagine now) we had no overseas service.

We’d never been overseas so when the call came in 1960 for the first battalion to go overseas it was a huge uplift for our army. We’d never served abroad and well over 95 percent of those in the army volunteered.

It was voluntary by the way. It might sound slightly strange now but during my period in the army you would volunteer to go overseas. Of course at that stage for the army the uplift was to go overseas, get experience and go to a country that we had no knowledge of whatsoever, which was the Congo.

What did you know about the Congo before you were deployed?

Our experiences of the Congo were actually nil. When we were being briefed before we went we didn’t even have a map of the Congo so we were laying out these school maps of the world. The people who were briefing us knew this and we were told that we would see lions and elephants. We never did and we were also told that it would be peaceful and it certainly wasn’t!

We had some knowledge I suppose because Sir Roger Casement had been in the Congo and written a lot of documents about how badly the natives were treated and for that he was knighted. Later on he was hanged unfortunately during the 1916 troubles.

I suppose we also had a little bit of knowledge from missionaries but it would be very little, very scant. For most of us in Ireland we’d never been there and we had nobody really to tell us what we were letting ourselves in for.

I suppose the main thing about it at that time was idealism. Its one of the things that’s neglected in schools today to talk about idealism but the vast majority who went to the Congo didn’t know where it was. The soldiers didn’t know how much they were going to get in terms of allowances so there was no question of money. But there was an idealistic thing that we were going out there to give ‘emancipation’ as we called it to the black population. That was very strong.

It was probably taught into us by religious people who taught us in school, which in my case was the Christian Brothers. We still have that kind of regard, which is why we’re serving so successfully as peacekeepers in the Lebanon and Syria etc. Long may that last. It was definitely idealism that drove us all and of course the whole idea of adventure.

How did it feel to be serving in the UN?

We were the first to go from ‘peacekeeping’ to ‘peace enforcement’. We were still called peacekeepers for a long time afterwards but we had a difficulty in that we were really training for peacekeeping whereas-and maybe to an extent this is why it appealed to a neutral country-which is why we were initially very much accepted by the Belgians.

They still had huge control over the Congo even though they had given so-called ‘independence’ to the Congolese themselves. Certainly the Belgians in Katanga ruled the roost through this huge mining company, there’s no doubt about that. The mines themselves were in the copper belt. Copper was huge at the time and they also mined for diamonds and cobalt. What we didn’t know was that they were also mining for uranium that was supposed to have been used in the atom bomb in Hiroshima and Nagasaki so the Americans had a strategic interest there.

We were very naïve. First of all we were under-resourced and the equipment we had was antiquated. We were virtually without any transport when we went in there so we had to borrow or beg for transport to get us from place to place.

The UN brigade had three battalions, one was Irish and one was Swedish but the third one was the Indians. Their interpretation of peacekeeping was totally different from ours and I suppose a lot of them would have come straight from Kashmir where the fighting was going on between themselves and Pakistan. They had experienced conflict whereas we had been the living the illusion of ‘peacekeeping’ and not realising that trouble was just around the door when we went into Jadotville.

How were the Irish troops treated by the local population?

We never had any difficulties from the local population whatsoever, in fact we were welcomed. There was never any aggression in any sense but we did gradually start to realise that there were other things at play, which were the mercenaries. They were quite conspicuous around the area in Elisabethville, which was the capital of Katanga. It was gradually obvious that they were pulling the strings but there was no conflict.

The conflict only really started about two months after we had our first interaction during Operation Rum Punch. The whole idea was to get these people out who we called ‘mercenaries’. However, a lot of them were Belgians who were born in the Congo and regarded Belgium as their second home. We called them ‘mercenaries’ and they and some French in the Katangese army controlled [Moïse] Tshombe (president of secessionist Katanga) in that they would be giving him directions about what way to go and resourcing him etc.

So the idea was to get them out, hand the whole place over back to the Katangese and Congolese people and we thought we did that successfully. We got rid of them but unfortunately many more mercenaries came back. Towards the end I think there was about 1,000 mercenaries in Kantanga that were probably being very well paid by Tshombe.

The other side of that was that there was huge British involvement because you had northern and southern Rhodesia on the border. There was a tripartite arrangement between those two and the whole idea was that there might be some kind of unity with Katanga. They were strategically very important worldwide to British interests.

So here we were-this little, small, neutral country that wasn’t involved in or even understood world politics that got involved in what turned out to be this huge, political conflict. It was way beyond what we ever realised we were letting ourselves in for.

PRELUDE TO A SIEGE

What was the background to A Company’s involvement at the Siege of Jadotville?

The background was that we had carried out our actions. We’d got rid of all the mercenaries and we were then guarding the airport in Elisabethville at the start of September. On the Sunday morning Pat Quinlan came to us and said, “Pack up immediately, we’re going to a place called Jadotville.” Of course we all asked, “Why are we going here?” He said, “There’s going to be a riot. The white population are fearful and they want the UN in there to guard them in case there are riots”

So we rushed and packed up our equipment and unfortunately we didn’t have transport so the Swedish contingent provided the trucks. We loaded up the trucks but we had to leave our heavy mortars behind us and our pack rations too because we didn’t have room to bring them but we were assured they would be sent down. We drove into Jadotville, which was about 90 miles away, and as we were going across the Lufira bridge we met some of our compatriots from B Company who were returning from Jadotville.

What had happened was a week prior to us going into Jadotville a Swedish force under Major Mide and the Irish B Company from 35th Battalion had gone in. Just think of this, two battalions were told to go in immediately a week prior to us with the same mission, which was to stop the possibility of rioting. Both companies went in and they didn’t dig in. Mide went to see the bürgermeister who was the mayor who told him there was no problem, to get out of Jadotville because they didn’t want the UN. Mide then rangs the Swedish commander who said, “Withdraw.”

As they were withdrawing B Company also withdrew-that’s a force of about 300 troops with Swedish APCs. They withdrew and we – a force of about 150-were sent in and nobody to this day can explain why that was or why were we sent in there.

When we went in Commandant Pat Quinlan had the foresight to dig in within two or three days because he wasn’t happy with what was happening. He was told by the bürgermeister on the Monday to get out of Jadotville saying, “We do not want you here.” So here we were, lured into this place and directed in by who knows. Nobody to this day will admit who it was but it certainly came from the UN headquarters somewhere on high and we were lured into this situation. Pat Quinlan immediately contacted the battalion and said, “Look, we’re not wanted here, there is no rioting. I suggest that you give me instructions. Should I withdraw?” He was told to stay where he was.

We had one truck for rations and the Swedes left us and took away all our transport. That wasn’t clearly understood either so we were left with two armoured cars, a truck, a Land Rover, an ambulance and a CO’s car and that was the sum total of what we had.

On the Tuesday we had the first incursion into our area by Katangese troops driving trucks up and down the main road but we were straddling that road on both sides. We occupied the same area that B Company had occupied. The UN had secured that area and told us that was where we would go.

These guys were driving up the road with fully armed troops but we had no way to stop them because they were quite entitled to drive up and down their own roads. This was where the peacekeeping started to unravel a little bit and after a day or two of this we urged Pat Quinlan to do something about this and he did. We put an armoured Land Rover with a Vickers machine gun outside our headquarters so that they could see that we were going to retaliate.

Obviously, they were trying to provoke us at this stage and we were beginning to see how vulnerable we were. Within two days Pat Quinlan gave an order to dig in, which we did. We had everybody dug in camouflaged within 24 hours. The locals wouldn’t give us rations: they wouldn’t deal with us in Jadotville at all so we sent a truck back to Elisabethville to get rations. They were stopped at the Lufira bridge which was about 10 miles away from Jadotville itself on the main road. They were held up by a very strong Katangese force and they were sent back so we had no rations except the ones that we had bought in that week.

That evening Pat Quinlan gave me instructions to go into Jadotville itself. I got three or four NCOs with me and drove down in the Land Rover. The railway gates were blocked and I remember getting out of the Land Rover where we had stopped and I could see about maybe a company of fully armed Katangese troops around the area. I asked to see one of the officers who I imagine was a Belgian and he came up. I said, “We have freedom of movement” but he said, “No, you’re not going in there. My instructions are that no one is to pass the gate.” I immediately reported that back to Pat Quinlan and within three days we were actually being attacked.

What armoured cars and weapons did you have at Jadotville?

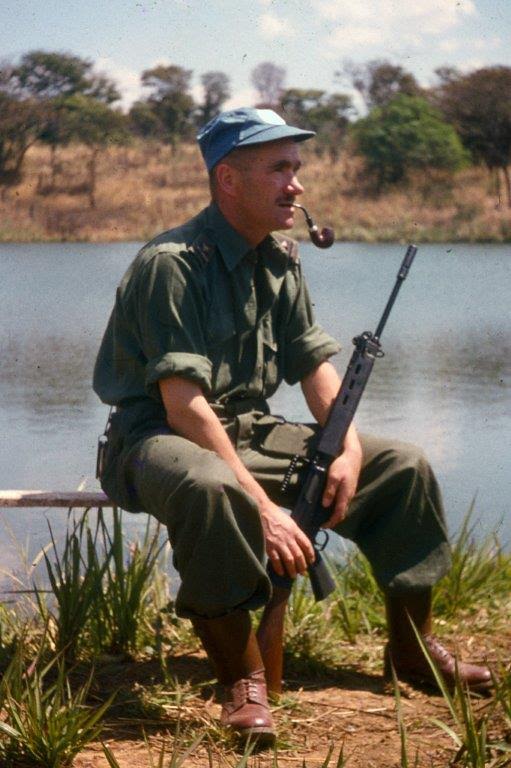

We had two World War II armoured cars that had been homemade in Ireland that carried a Vickers machine gun in each of them. The weapons that the private soldier would have had were FN rifles. These were Belgian and had been issued to us just prior to us leaving Ireland. They were reasonably modern.

We also had 81mm mortars but these were the ones that were left behind and never arrived so we had 60mm mortars. They had a shot range of about a mile and we had about four 84mm anti-tank guns. The officers and NCOs equipment included Gustav sub-machine guns with a range of about 100 yards and Webley revolvers, which were pretty ancient at that stage.

So that was our main armament. We had no mines, barbed wire or trip flares or anything like that for a proper defensive situation.

AN INTENSE ENGAGEMENT

How did the siege begin for you on 13 September 1961?

I had been up all night on the 12th. I was the orderly officer (duty officer) and we’d heard a lot of rumours.

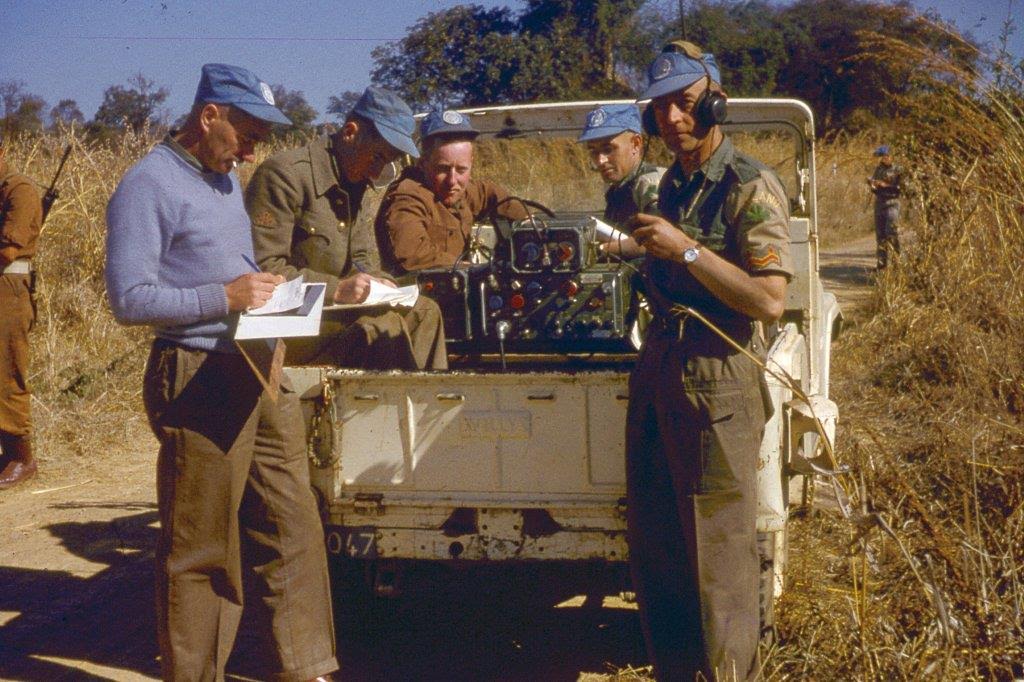

Our communications system was appalling in Jadotville. We had what was known as a ‘C12’, which was our main radio back to headquarters in Elisabethville to the battalion. The range of that was very limited, it was about 50-60 miles and we were transmitting at 90 miles. Through various methods the signals corps were able to manage to sometimes get the range and transmit at night. We transmitted in Irish quite a bit because we were afraid the mercenaries were listening to our messages, which they were.

A lot of the batteries on the radios went and we had no internal communications so our only direct link was one line – the C12 – back to headquarters so we were quite limited. A lot of the information that we were getting was being given to us locally. First of all we had an Irish civilian lad called Charles Kearney who was from Wexford. He was giving us information and telling us exactly what was happening including that the mercenaries were stirring up the native population and there could be trouble. He also gave us a map stating where a lot of the mercenaries were located.

Some of the native lads who were working for us also gave us information that things were hotting up. That particular night of the 12-13th September we were told that there was every possibility of being attacked, which was pretty harrowing. We had a number of people already in the trenches but not all of them at that stage.

At 7am I got a message from headquarters that Operation Morthor [the UN operation to disarm mercenaries and gendarmeries in Katanga] had taken place in Elisabethville and that all was well. I was also told to inform Pat Quinlan and be on the alert so I immediately did. However, the situation wasn’t as secure as it appeared. What happened was the Katangese already knew what was going to happen – their intelligence was first class. They had already occupied the post office [in Elisabethville] and other locations and when the UN forces came to occupy them they retaliated and the firing started. The Indians [serving with the UN] went into the post office and killed about 30 paratroopers.

The Katangese had some good soldiers and some of them were extremely well trained. They weren’t fighting with bows and arrows or anything like that and they had a very strong gendarmerie. Then of course they had about 500-600 mercenaries, some of whom had been in Algeria in the French Foreign Legion.

Some of them had moved after Algeria gained its independence and they ended up in the Congo. There were also Belgians and other nationalities as well so we were up against a pretty strong force. They were tremendously well equipped in comparison to what we had as was proved later by the arrival of the Fouga jet.

We were not aware of this on that particular morning when two of our lads were killed in Elisabethville as well as quite a few wounded. On both sides there was now no question there was trouble. I relayed a message to Pat Quinlan who then told me to go down and elect the two forward platoons who were nearest to the town at Jadotville. The only vehicle I could get was the ambulance and I drove down with the doctor who was complaining that I was taking his transport.

Just as I was about to turn left through the first crowd I could see a truck just parked across the road from the bus depot and that was the first sight we had of Katangese troops. They were fully armed and were dismounting from the truck. As I turned to the next platoon who were going to Mass the first shots rang out.

I honked the horn at the crowd going to Mass who then dispersed and I moved back down to headquarters. Pat Quinlan had his platoon commanders with him and he was directing them and giving them instructions. They moved off fairly quickly to their areas. This was about 7am.

Things then quietened down for a little while when all of a sudden Quinlan gave me instructions to set up a roadblock near our own area. We were the last platoon closest to the bridge but as I was setting up the roadblock the first ‘crump’ of mortars happened. I couldn’t believe it: it was a beautiful morning and you could almost hear the click of the rounds that were being fired from the mortars. That was the start of the fighting.

Several mortars fell, not in our area but we had no idea during that whole conflict of what was happening in other areas because the communications were absolutely nil. Shortly after the mortars started to fall they opened up with what was later on proved to be .05 heavy French machine guns from the area of the golf course and our lads were pinned down.

One of the support platoon commanders Captain Liam Donnelly later said to us, “There was just chaos in the beginning, they didn’t know what was happening. We didn’t expect to be attacked or to be fired on but gradually the lads got together and sorted each other out. The NCOs were brilliant and they were able to retaliate and fire back.” Most of them managed to inflict casualties on the other side because they were very naïve travelling around the golf course in Land Rovers and things like that. The Vickers machine guns were pretty effective along with the 60mm mortars.

That was the first morning and then at about 9am we had our first casualty. One of the lads was shot through the groin and that was the first person to be wounded during that action.

The follow up to that was that the firing lasted about an hour and just as I had set up the roadblock I got a call from one of my platoon NCOs shouting that we were under attack. I ran across, jumped into the forward trench and Corporal Foley was there pointing out where we could just see people coming through the bush. The range would have been at about 500 yards and the platoon in front of us was starting to fire and then everybody was firing.

We could see them advancing closer and closer and I found that I had a Gustav, which had a range of about 100 yards. I gradually took over the Bren gun from my Bren gun operator and that fighting lasted for about half an hour. You could see them scattering but they stopped first at about 300 yards away from us. You could clearly see them advancing from the bush and they’d obviously been encouraged by the mercenaries. But suddenly they started to stagger and rushed back through the bush. I can tell you that the feeling of elation was fantastic in that we’d won our first battle.

That was also on Day One and firing continued sporadically during the day. That night Pat Quinlan called us late at about 10pm. They had vacated the headquarters to a villa and he told us that Force Kane [a UN relief force] was on its way to the Lufira bridge and that we would be relieved the following morning. We went back to tell the lads that it was fantastic that a relief column was coming.

Late that night we could hear some firing from the bridge and Pat Quinlan called us back again early in the morning to say, “I don’t want you to tell the troops but Force Kane has returned to Elisabethville.” That was some shock of course, we couldn’t believe that we weren’t going to be relieved. Suddenly they’d gone 90 miles all the way back to Elisabethville without leaving any force on the bridge. We couldn’t figure this one out at all.

So we were trying to digest that and were having a pretty heavy night. It was the first time the lads had been under fire. They were jittery and were sometimes firing at anything that moved, which put people in danger. It was difficult to control people and get them to rest but gradually we did. It’s amazing how adrenalin really keeps you going when you start realising, “Jesus, we’re going to be killed here.” This had gone from peacekeeping to peace enforcement.

Can you describe how you directed mortar fire during the siege on 14 September 1961?

We had the disappointment of not being relieved but the second day was the “Shock Day” because we came under mortar fire early in the morning. One of sergeants in the platoon next door to me – Walter Hegarty – was hit by a mortar bomb but luckily the shrapnel only hit him in the back and the buttocks and he had to be taken away to the casualty station.

Sean Foley was a brilliant NCO and he spotted a mortar position and called up one of the 60mm mortar crew. We engaged them and after about 30 minutes there was a flash in the enemy area. We don’t know what happened or whether we hit their mortars or ammunition but the mortar fire died down and we were elated and clapped ourselves on the back.

What was it like to be attacked by a Fouga jet fighter?

I suppose the biggest shock for us at about 11am on 14 September having gone through all of that, survived and beaten off this second attack I could hear the sound of an aircraft. He came down the valley right in front of us, turned, wheeled and that at that time you could practically see the pilot inside. It turned out to be a Fouga jet and he waggled his wings. We had no idea that they had their own air force, we had no knowledge about that at all but they had an air force within 50 miles away at Kolwezi.

So he waggles his wings and we look up. At that time, I’m certain that we could have taken him down because he was flying so slowly but he suddenly disappeared. The question was, “What’s he doing?” Within an hour he was back down the valley doing the same thing but this time he shot straight up into the sky and all of a sudden there was a shout, “Get down! Get down!” You could hear the rattle of the machine guns as he strafed our headquarters and the next thing were two loud explosions as the bombs exploded. They were relatively small compared with what we have now but they created huge explosions on the forecourt of the petrol station where we staying. Obviously they set fire to the pumps in front of the petrol station and at that stage we had no idea if there was anybody killed or what had happened but suddenly he was gone.

That happened two or three times that day. It took him an hour to get to Kolwezi to refuel and get back again so you could maybe judge when he was going to come back. The second time he came in Pat Quinlan got two of the armoured cars to fire crossways as a kind of anti-aircraft firing but of course you could hardly see him coming down and we didn’t have any automated fire. He was gone before the lads could even press the triggers on their guns and he dropped two more bombs.

One of them hit a trench on a machine gun squad and the trench collapsed in on the squad themselves. They had to be pulled out but luckily enough they were just shell-shocked. How they were not killed I don’t know.

So that lasted for most of that day. Everything else you could counter but the problem with the Fouga jet was that you didn’t know where he was coming from, you didn’t know from what end he was going to come at you and that was pretty scary. We had to work very hard on morale to try and get some of the lads together because it was probably the biggest shock we had. We didn’t expect to be attacked, we didn’t expect to be mortared, we didn’t expect to be machine-gunned but by God we never expected that we were going to be attacked by a jet aircraft.

During the siege what would you do to maintain your platoon’s morale?

As an officer you have to maintain their morale as their leader. They have to see that you’re concerned about them, that you’re communicating with them as best you can but also that you’re not hiding in a trench while they’re out there fighting. The fact that I was out in the front trench was an indication that I was out there putting my life at risk the same as they were.

Also, the heat was tremendous:you’re talking about 90-100 degrees (Fahrenheit) and although we had some cover in the trenches it was intense. Then you had flies and dust along with the fact that you’re tense and under huge stress. You have to look after your own troops too. Even though you might be afraid and are shaking you still have to be there. Its not “John Wayne” – its reality.

I also have to say that the NCOs were terrific. Through them you can as one individual control all the lads in your platoon, company or battalion. In my case I did it through the NCOs in my platoon.

One of the things that Pat Quinlan really did was important training before we went to the Congo. For some reason he was one of the few that anticipated trouble. People will say that he was too concerned about digging in and things like that but he was always concerned about how we would react to situations and how good our training was.

Can you describe what happened during an incident involving the UN relief helicopter?

Friday for me was a very difficult day in that we were under fire in the forward trench and at this stage we had pretty much been without sleep for about three days. The troops in my trenches were obviously tired so I had to rotate them. As we were rotating them we came under mortar fire and at that stage I told them to get out. I was in a trench myself and that was scary because the mortars were falling about all over the place. I must relay the fact that religion goes out the door when you’re that close to the reality but I said a quick prayer that if ever I got out of it I’d call my son Paul Jude [the Roman Catholic patron saint of lost causes] and he’s now a colonel in the Irish Army.

So we did survive and we rotated them. In the evening I was told by Pat Quinlan that the second relief column was coming and they would be at the Lufira bridge on Saturday morning. That was fantastic when we were able to tell that to the troops. We spent the night thinking how would we greet them and give them a guard of honour-it would be fabulous to be relieved at last.

We had no water at this stage, our rations were running out and the ammunition was getting low. We knew that this would have to be the breakthrough and on the Saturday morning we could hear the firing on the Lufira bridge. The Fouga jet came over but he ignored us and it turned out that he went to the Lufira bridge and dropped two bombs. The relief column suffered three casualties with three killed on the bridge that morning. We knew nothing about this but the Fouga jet went back to Kolwezi and somebody shouted that there was another aircraft in the sky.

We saw a UN helicopter coming in and two brave lads went out and put a marker down for it to land. As it came closer the camouflage on my own trench flew off and when we looked up we could see the rotors of the helicopter just above our heads. I told my platoon sergeant and my signaller to get out because I could see if these guys were going to mortar us it would be the helicopter that they would hit.

As we were getting out we saw the two helicopter pilots. One was a Norwegian Lieutenant Bjorn Hovden and the other was Warrant Officer Eric Thors who was Swedish. We got the two of them into our trench and I remember Eric Thors shaking my hand saying, “Its better than Dien Bien Phu!”

The sequel of it was that we had 10 Jerry cans of water on the helicopter and when there was a lull in the fighting some of the lads were able to get out and get them. However, they were all contaminated. Nobody had cleaned out the Jerry cans before they were flown by these very brave helicopter pilots. They practically crash-landed their helicopter onto our position because the red light was appearing on it and they thought they wouldn’t take off again. For all of that the Jerry cans were useless.

In addition, they had brought a half-bag of mail and somebody called my name. I gingerly put my hand out of the trench and was told I had a letter from Ireland. I thought that was great but when I opened the letter it was a bill from a book company to whom I owed about £2!

What were the circumstances that led to the ceasefire on 17 September 1961?

From a Katangese and mercenary point of view at Jadotville they had a UN force at the bridge who looked as though they might get across. They now had a helicopter to deal with so they had no idea what was being sent in that so at 3pm Pat Quinlan got a call from the bürgermeister. There was a phone line kept open from his villa to the bürgermeister’s office in Jadotville. Some have said that Quinlan should never have left that line open but at least it was some communication between them and us.

The bürgermeister had been on it a few times to look for a ceasefire at night so they could take away their wounded etc, which had been agreed to by Quinlan. But this particular day he said, “Can we have a ceasefire?” Quinlan said yes and then laid down terms that we should be given our water, that the jet should be grounded, that there should be a no-mans-land between Jadotville, our own position was to be policed by their police and our own troops and that all of their troops should return to their barracks.

The bürgermeister agreed and we had an agreement. For the first time that evening we left our trenches. We were able to get out and we took photographs. We were all glad to be alive and we visited our wounded men but luckily nobody had been killed. We couldn’t believe that nobody had been killed.

It was terrific that we had got a ceasefire and our lads (we thought) were at the bridge ready to cross. But then Pat Quinlan called us in at about 6pm that evening and told us the bad news that our relief column had gone. They had left the Lufira bridge and had gone back to Elisabethville so that was it. That was the end of it because with no contact on the bridge the second failure of a fairly strong force-we couldn’t believe it. Our fate was sealed at that stage, we had no card to play with now. When they sued for peace Pat Quinlan had all the strong cards but suddenly the whole thing was reversed. In military parlance if you’re on an objective – even if you have to reduce your strength on it – you always maintain contact with the enemy and in this case there was no contact.

I’m using the wording here very loosely because we didn’t see the Katangese as our enemy, it was probably more the mercenaries but the word ‘enemy’ didn’t arise. Its strange going from peacekeeping to peace enforcement and it wasn’t in our nature to kill anybody so we didn’t want or ask it to happen. It was not of our making.

Somebody once asked the question, “How did you feel about this?” and I felt that I had to defend myself and my troops. It was a defence: we were defending ourselves, we were not being aggressive and it was never our intention to have trouble with anybody – certainly not the local populace. However, you do retaliate if people are trying to kill you.

What was your opinion of the Katangan gendarmeries and mercenaries fighting ability?

We were lucky. They were well trained they were not a rabble. We were in a situation where there was no experience of the Congo at all at home. Number two, nobody really knew what was happening out there, there was not the instant correspondence that there is today such as instant TV and camera shots coming back from a conflict. It took weeks for information to circulate and get back from that conflict.

The assumption was that we were fighting native tribesmen at Jadotville but Katanga was a hugely organised province. It was the most lucrative and wealthy of all the provinces and it used to provide 50 percent of the whole economy of the Congo. They were training troops, they had an air force that we knew nothing about, paid paratroopers and the gendarmerie was also pretty well trained. Additionally, they had the benefit of about 500 hugely trained and experienced mercenaries. So we were up against a pretty formidable force and their equipment was certainly superior to what we had.

What does ‘gendarmerie’ mean in a Katangan context in 1961?

They had their own police but they had two forces. One was the ordinary unarmed civilian police and then they had the gendarmerie. Some of them were basically police but the others were the army and they also had trained paratroopers who in our experience were eventually taken captive.

What were the circumstances that led to the final ceasefire and reluctant surrender?

By the Saturday night we had no strength on our side at all. I remember Tom Quinlan-who was a lieutenant in No.2 Platoon and myself shared a room in headquarters. We went back the first night to sleep but we couldn’t and we both realised, “We’re in the shite here”. We had no more cards to play and what were we going to do? We had no ammunition, no water, our food situation was getting dire and the main problem was that people were getting tired.

Its like playing a match and you’re putting everything into the game and you’re having to play extra time. You’re putting all your energies into the game but then someone says, “We’re going to have to play another 30 minutes.” We were now trying to resurrect ourselves from an engagement that we thought was over and we were going to welcome our troops from across the bridge and that the ‘enemy’ had sued for peace.

Suddenly we were in a new ball game and we were having to start all over again. To try and even get everybody back into the trenches – exhausted as everybody was – was going to be a huge, huge problem. So when there was no sign of water being restored on the Sunday and we suddenly saw the Katangese encroaching on our position there was very little we could do because we’d agreed to a ceasefire.

Pat Quinlan first went into Jadotville early in the morning and he was met by a number of mercenaries. He went in looking for water and he went into one of the local hotels. When he went into the bar the mercenaries in there went up to him to show their wounds and congratulated and saluted him!

When he came back he got a call from the bürgermeister saying that the Godefroid Munongo, the Minister of the Interior had arrived. Pat Quinlan was called in and they had a conference. Munongo said that he was happy enough with the way the Irish had fought but he was very annoyed about the way the Indians had killed the paratroopers during the start of the fighting in Elisabethville. He said that we’d have to vacate our positions immediately or else there would be 2,000 troops surrounding us.

We were totally surrounded at this stage, our troops had gone from the bridge and we were isolated. Pat Quinlan then said the UN would send in aircraft to bomb Jadotville but Munongo said, “That’s not going to happen.” How true that was because the UN tried to get aircraft from Ethiopia but the Ethiopian jets were blocked by the British because at that stage the airspace around Katanga and the Congo was virtually controlled by the different British protectorates. The jets couldn’t fly over British airspace.

He knew this and they knew it, we had no cards. Pat Quinlan called a conference later that evening and laid out the situation. I remember one of the clinchers was that we had two armoured cars but their machine guns were gone having fired thousands of rounds and the locks on the machine guns were also gone. So they were out, we had no transport ourselves and we would have had to fight to get out of the trenches and the Lufira bridge was 10 miles away. The troops were totally exhausted and to travel 90 miles virtually on foot back to Elisabethville through enemy territory with the Fouga jet on the loose-it would never have been on. We would never have succeeded.

Not that we didn’t want to – we did. The platoon commanders said, “We think we can fight on” but Pat Quinlan had to make the decision in the light of no food, no water, practically no ammunition and no transport to take us back 90 miles. It was a deteriorating situation and there was no support, we were left on our own. He had to make the decision and that was his decision.

None of us officers wanted to surrender. In fairness to Quinlan he laid out the situation clearly to everybody and when we realised it what could you have done? My own view was that we would have probably lasted another 24 hours before we would have had huge casualties and who was going to relieve us? The rest of the battalions were in trouble in Elisabethville. What we had done was contained quite a number of the Katangese army who would otherwise have been in Elisabethville and caused even more trouble.

Was there any point where you thought you might not survive?

I suppose the situation was that we were quite confident that we would survive until that Sunday evening. The last thing we ever thought of was that we would be put in that position. We were sure that the relief column at this stage would break through or indeed if they didn’t break through that they would stay at the bridge, which would encourage us. But in fact they were gone by that evening. It was a huge blow to everybody’s morale and we suddenly realised that we were totally isolated. We acquitted ourselves very well under the circumstances and looking back it was a dreadful decision for Pat Quinlan to have to make.

What was your opinion of Commandant Patrick Quinlan?

Funnily enough, we were fortunate in one way that we had an excellent commander in Commandant Pat Quinlan. He wasn’t the perfect man that he’s often portrayed as, I had grave difficulties with Pat Quinlan. It was very difficult for me because I was a young, inexperienced officer and he demanded the highest standards. He insisted that we were properly trained before we even went there.

For some reason before we went we were told that were would be a lot of rioting. Now there had been rioting all over the Congo when the Belgians left so we spent a lot of time doing anti-riot drills and mine was unfortunate in that my platoon could never measure up to Pat Quinlan. I fell foul of him quite a bit so when I had the chance to go off and do patrols in the Congo I nearly jumped at the opportunity just to get away from him!

But, when the chips were down and the trouble started he turned out to be a brilliant officer and leader. That’s the difference between the personality that you might not like but by God what a commander.

CAPTIVITY

How did it feel to become a prisoner and what were conditions like during your captivity?

I suppose it wasn’t the captivity itself but the realisation that you’re on a high (in this case adrenalin) and the coming down is just unthinkable. It was the realisation of, “What’s going on? Why is this happening to us?” We didn’t want this to happen, we fought as best we could and we thought we had won.

We didn’t want to do the blame game but we still thought, “If only they had stayed at the bridge” and then the shock of thinking, “Christ Almighty, we’re going to be prisoners!” That was probably worse than actually being a prisoner.

There were two instances that I recall. One was the second morning when we were prisoners and we were in an old, deserted, musty, dusty hotel and we were sleeping on the floor on the first night. In the early hours of the morning we heard a man pulling up on the side of the road. We looked out and we saw a coffin in the back of a Land Rover. The question was, “Was this for one of us?” We had no idea, nobody was telling us what was about to happen. The anxiety grew and after about an hour the Katangese paratroopers came out with a Katangese flag and put it over the coffin and off they went.

The other one was when we were being brought to Kolwezi to Jadotville where they’d set up a proper POW camp we were stopped at a village and they left us there for about an hour. We were surrounded by mainly native women and children and they were throwing pieces of grass at the windows of the buses and making threatening gestures. There was no doubt that if they’d got the chance they would have torn us to pieces. We reckoned afterwards that maybe they were relatives or families of the Katangese that had been killed. That was dreadful, terrible and very harrowing.

Then of course when we went to Kolwezi some of the lads were beaten up on the first night and there was a bit of panic about this and they passed over. Some of the lads had grenades in their kitbags and they passed them over to me! I had to find a hiding place in the back of the seats of the buses and get rid of anything they had because if you were caught with anything they’d beat you up. That was harrowing.

We were never searched but we had weapons like grenades, bayonets and I had a radio that I hid. I kept that during the whole period even though we were searched when we were brought away to Kolwezi as prisoners. I smuggled it in a rice bag and they never discovered it.

The UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld was killed in a plane crash shortly after the ceasefire and we knew about it from the British BBC World Service from the radio that I had in my haversack.

Conditions were bad and we slept for days on the floors but through the interference and involvement of Pat Quinlan and his personality he eventually got the guards to listen to him and conditions started to gradually get a little bit better.

He was fantastic, the role he played even in captivity was unique. It would only be someone as forthright as Pat Quinlan who succeeded in keeping up the morale and focus. He was fearless really.

Did you witness Pat Quinlan negotiate with Katangan president Moïse Tshombe?

I did yes. When Quinlan arrived there in the hotel, he gave instructions that we would make Molotov cocktails. The reason we could make them was that they allowed us to bring our cooking equipment. The cooking equipment at that stage were petrol-driven gas fires. So we had petrol and we were able to put it into the Molotov cocktails and we stored them in the top of the roof of the hotel. If anything happened we had a designated spot where we could use them.

It was on the Sunday when Tshombe came with his entourage and he was surrounded by quite a few of the locals and Belgian people who were cheering. Quinlan told us to go on the roof just in case anything happened. Quite a few photographs were taken and Quinlan did well meeting him. He told Tshombe that we were from the UN and should have freedom of movement while we were there and that our role was peacekeeping. He also said that because we were attacked we should be immediately released but Tshombe just looked at him and ignored him. He turned on his heels and walked off. Tshombe was with us for about five to ten minutes but it was a propaganda stunt as far as the Belgians were concerned.

RELEASE AND AFTERMATH

What were the circumstances of your release and the subsequent of the Irish Army and government towards the Jadotville veterans?

We were prisoners for six to seven weeks. When we were brought back from Kolwezi to Elisabethville we had planned that we were not going to go back again. I remember that we discussed that each platoon commander on each bus would arrange to attack the troops guarding the bases and that we would take it over if we thought we were going to be brought back again and not going to be released.

That was tense to think that we planned to take over the buses. In hindsight it was a crazy idea because they had troops on the buses and also guards travelling in Jeeps on each side. There was no way that we could coordinate or signal each other but it was a plan and the potential was there whether we were going to be released or not.

However, when we got to Elisabethville we could see the UN troops so that was a fantastic and really wonderful feeling. It was great to be back with our compatriots from B Company who told us what happened at the Lufira bridge and how they had been attacked and ambushed. Some of their lads had been shot and wounded and we told them what had happened with us so we were able to share what happened to each other. That was ok but there was a bit of tension that started to develop with some thinking that we should have broken out etc.

Then we returned home as heroes but the troubles continued on up to Christmas where there was trouble in Elisabethville again and our troops were involved in that. When we got home to Athlone we got treated as heroes but the reaction of the army was slightly different. An ‘anti’ feeling started to develop, “Why did we surrender? You shouldn’t have done it, you were only fighting a crowd of Balubas armed with bows and arrows.”

This was from people who knew no better. Nobody understood what Pat Quinlan had gone through other than ourselves and that lasted for about 40 years afterwards. Eventually, somebody took up the cudgel and we finally got some recognition in that the army agreed to have a monument set up in Custume Barracks and the veterans were invited over for the official opening of it.

But it still didn’t clear the air with acknowledging the courageous actions of Pat Quinlan and the company and how they had behaved and fought. They had done it gallantly and bravely and in recent years through the intervention of a veteran called John Gorman the story came out. Prior to him Liam Donnelly ,who had been in command of a support platoon, was a commandant when he retired and he made a submission through the army to the chiefs of staff. It was through him that they got involved.

John then got involved on the political side and he has ever since been pushing for proper recognition and he has done a fantastic job. He’s devoted his whole life to it really even though he was only 17 and a private soldier at the time. It has borne fruit and there was a lot of effort last year because of the film to get a scroll and we got a [presidential] unit citation.

It is the significance to us of total vindication and recognition first of all of our heroic company commander Pat Quinlan. I couldn’t praise him higher. I served with him later on in the command depot where they ran courses for NCOs and by God did they come out right on after the training that he insisted on. Equally, he was a neighbour of mine: he lived about six doors away from me for many years when we lived in Athlone. I had a lot of time for him, not on a social level because he could still be difficult but what is that compared to his bravery which was just unbelievable.

Were you recommended for a decoration by Pat Quinlan?

I was. The problem there was (and not just for myself) Pat Quinlan had recommended a number of decorations and promotions but we didn’t have an army decoration at that time. There was one but that would be the equivalent to a Victoria Cross for gallantry and we didn’t have a specific award for the Congo. So he had recommended a number of decorations, including myself, that went to the highest level. My platoon sergeant was one of the ones that recommended me as well as Pat Quinlan and the adjutant general of the forces recommended it but the board rejected every single one of them. Nobody from A Company got any award for Jadotville.

There were prolific politics at a high level. There were wrong messages probably and there was a stigma that it shouldn’t have happened, that we should have fought to the death etc. To me it’s interesting when I talk to young officers and trainees and they look aghast. It was a different era. Because of the Niemba Ambush [where nine Irish UN troops were killed by Baluba tribesmen in November 1960] there was an expectation that nobody should be coming back. It might sound a bit macabre but there was a kind of death wish.

Pat Quinlan should have been lauded by the politicians. You imagine today in the UK if some operation anywhere had resulted in a number of soldiers killed the politicians would be running for cover all over the place whereas Pat Quinlan saved all our skins and brought all his troops safely. He just didn’t get the credit he should have got.

It almost seems like there was an almost Victorian sense of sacrifice?

That’s exactly it. It was that attitude of, “You’d be better off coming back dead.”

What was your opinion of the UN high command and some of the personalities involved in handling the Jadotville affair?

First of all I would say that the intelligence system in the UN was appalling. There was practically no intelligence about the conflict we were going to find ourselves in. There was a difficulty, which is perhaps still there to an extent, of different nationalities working together. We had never worked with any other nationality when we left Ireland and suddenly we were pitched into a situation where we had about 10 different nationalities in the Congo initially. So you can imagine that it became a little bit territorial as well. You want your area, you want to get the best of this and there was a naivety in the case of the Irish that we were very small fish in this big pond. By the time we got to exert ourselves all the best locations had been taken over by other nationalities and there was that difficulty of trying to get the nationalities to work together.

However, I could see the merit in the UN force. It would always be difficult but if you’re not working together with other forces its very difficult to work together in a conflict situation. I thought that the Irish acquitted themselves fantastically well. The troops were tremendously adaptable and their current work in peacekeeping is very much misunderstood. What they do in the countries they go to is tremendous and indeed by being Irish they had no colonial baggage. We can proudly go into these countries and probably empathise with them in a lot of ways. We never had any axe to grind with the Congolese people.

With regards to the question about the headquarters I couldn’t comment. We found them to be remote from us really. We cannot understand who made the decision to send us into Jadotville having had two companies already there and then to send one company without any explanation. Pat Quinlan begged them to make a decision particularly as we were not wanted there and wanted to leave. They just told us that everything was ok and knew that Operation Morthor was going to take place. They didn’t even alert him that Operation Morthor was going to take place and that’s where I would have huge difficulties with regard to the role some people played.

Surely if you have an isolated company in a situation 90 miles from where your action is going to take place you would ultimately tell them in advance that there was a major operation taking place within a couple of days of them being isolated. And you would make every effort to get them out immediately before you start the operation-that’s common sense.

The other thing which to this day I cannot understand is if you have a helicopter and you’ve got some of your compatriots out there 90 miles away and they’re desperate for water, ammunition and help would you just send them 10 Jerry cans of contaminated water? How crazy can you get!

Something was amiss, maybe because of a naivety that maybe the Katangese would give in easily but again it all goes back to intelligence. That’s the key in most areas with any action or situation militarily. If you don’t have proper intelligence you’re in trouble and you must know your opposite numbers, what their intentions are and what you need to get right. If you don’t know that you’re swimming around in a fog, you’ve no idea where you are. Intelligence is the key.

What is your opinion of the 2016 Netflix film The Siege of Jadotville?

The film gives off the impression that there were no officers there apart from Pat Quinlan, which was ridiculous. However the message did come across about the injustice of what was done. I was asked to give some advice for the film but they wanted to show it in a particular light.

The town looks different in the film to the actual reality. Jadotville itself was a fine town, and the Belgians lived there in fantastic conditions and we were envious, having left Ireland at that time. We were on the edge of the town and there were villas on both sides.

The native population lived in more primitive accommodation but the Belgians were pretty ok to the workers. When I say ‘ok’ obviously they weren’t getting huge money or anything but the town in the film was portrayed in the film as if it was some kind of Wild West place.

What more still needs to be done for the veterans in 2017 and beyond?

In our case – those who were in Jadotville – the families of the surviving veterans and those who are dead should be recognised. I think the [upcoming] commemorative medal should be hopefully be used to promote other people who have been involved in conflict as well. I’d hope that it would be a general medal to be produced for bravery of some kind. I think that would be a great fulfilment.

The other one that I keep on talking about – and I said it at the Unit Citation ceremony – is that there should be some recognition for those that helped us. In our particular case I’m thinking of Charles Kearney who put his life at risk and was almost shot. He was captured, imprisoned with us before he lost his job and very nearly his life. Then there are the Gurkha soldiers killed at the Lufira bridge, the members of B Company who were wounded at the bridge and of course the very brave helicopter pilots. We should have some way of giving them recognition.

It’s a shame that we don’t have a commemorative medal that we could award to them or their families and I think it would be a great gesture.

I would hope that the commemorative medal for Jadotville could be given to other units or individuals for acts of bravery, which should be recognised.

What are your final thoughts on the events surrounding the siege?

There is no recrimination. We insisted, even when the film was being produced, that we would not agree to have anything adverse said about any member of our battalion. The last thing I would want is recriminations and I would not want to point a finger of blame to anybody about what happened. The only thing I would ask of the UN is why we were sent into Jadotville and why were we not told about Operation Morthor.

These are the two big questions and I also suppose how long it took so long to recognise how brave Pat Quinlan was and how he commanded a very brave company who really fought to the best of their abilities to try and redeem the situation. I don’t have a chip on my shoulder. We look back and say, “Why did that happen?” but it’s gone and we have moved on.

The IUNVA is the association for serving and ex-service members of the Irish Defence Forces and Gardaí (Republic of Ireland Police Force). It is open to anyone from these organisations that have served at least 90 days service on a UN mission in a foreign country. The IUNVA’s primary role is to provide support and events for members and their families who have been affected by overseas service.

For more information visit: www.iunva.ie

Images courtesy of Noel Carey and Leo Quinlan