Dr Damien Fenton

Research Fellow

World War I Centennial History Programme

College of Humanities & Social Sciences

Massey University

Wellington, New Zealand

Why was the Gallipoli operation put forward and given the green light?

It was championed by Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, as a way to knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war in a single decisive blow. The War Council were persuaded to back Churchill’s plan on the proviso that it would not require the use of any modern warships from the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow nor any British forces already serving or earmarked for service on the Western Front. In other words, they were sold on the idea of a quick, low-cost and easy win against what was thought to be the weakest of the three empires arrayed against them.

What was the aim behind the operation?

The aim of the original plan was for a combined Anglo-French fleet under the command of a British admiral to force a passage past the Ottoman coastal defences guarding the Dardanelles Strait. Once this was achieved the Anglo-French fleet could proceed up the strait, through the Sea of Marmara and then on to its ultimate objective – the Ottoman capital of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul). At that point, confronted by the alarming sight of an allied battle fleet just offshore and under threat of having their capital flattened by naval bombardment, it was assumed the Ottoman government would have no choice but to surrender.

What technology, weapons and methods of warfare were used by the British at Gallipoli?

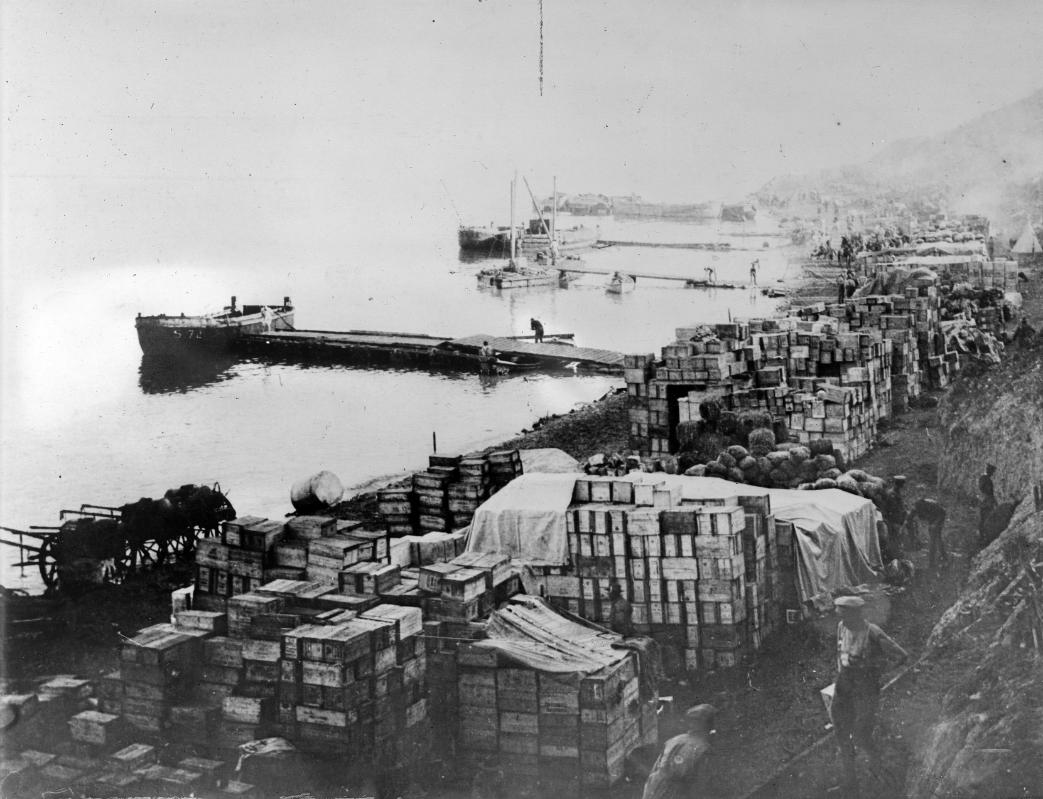

Both the Anglo-French fleet and the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF) that followed it were organised on an ad hoc basis using whatever men, weapons and equipment could be spared from the main war effort against the Germans. In practice this meant obsolescent pre-Dreadnaught battleships and armoured cruisers for the fleet and inadequately trained and equipped land forces that lacked the firepower available to their counterparts on the Western Front, especially in regard to artillery. Initial MEF tactics reflected the pre-war British Army training regimes used by the ANZAC, British and Indian Army troops alike, which proved to be hopelessly out-dated and especially disastrous on attack. Instead, the harsh new realities of trench warfare had to be learned on the job.

Was the Ottoman Empire really the ‘soft underbelly of Europe’?

In fairness to Churchill and other British leaders, the Ottoman Empire had long been regarded in diplomatic circles as the ‘sick man of Europe’ since the Crimean War 60 years earlier. Furthermore, the Italian victory over the Ottomans in the Libyan War (29 September 1911 to 18 October 1912) together with the comprehensive defeat of the Ottoman Army in the First Balkan War (8 October 1912 to 30 May 1913) by the ragtag armies of Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia and Montenegro seemed to confirm the Ottoman Empire’s reputation as a great power in terminal decline.

Why did it fail? Was it a case of poor preparation by the British or were the Ottomans stronger than first thought?

Both. The Ottoman military had spent many years before the war developing and finessing contingency plans for the defence of the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus from seaborne invasion. On the Ottoman entry into the war in November 1914, these plans were put into action with great effect. A series of underwater minefields were laid across the Dardanelles Strait and mobile batteries of modern field artillery deployed to augment the existing network of coastal fortifications guarding the strategic waterway. Meanwhile, the Anglo-French fleet, in addition to making do with old warships, was forced to rely on civilian-manned North Sea fishing trawlers converted to minesweepers to clear a path through the Ottoman defences. Unsurprisingly, this ad hoc approach was a failure, culminating in the disastrous all-out naval attack on 18 March that ended with one French and two British battleships sunk by mines and a 1,000 sailors dead.

Why were landings sanctioned after the ineffectiveness of the Royal Navy? Was it desperation or a possible good alternative tactic?

Despite the defeat of 18 March, Churchill, Kitchener and others in the War Council refused to give up on the Dardanelles strategy while the option of invading the Gallipoli Peninsula with a land force to eliminate the Ottoman coastal defences was yet to be tried. In theory, a plausible case could be made to attempt this option but only if such an attempt was supported by thorough planning and preparation along with a willingness to commit the large numbers of suitably-equipped and well-trained troops required to ensure success from the outset. Instead, most of the ad hoc organising principles and misguided assumptions about their Ottoman opponents that had undermined the naval effort were simply repeated when it came to creating the MEF and setting its objectives.

What was the bloodiest operation of the whole campaign?

For the MEF it was the Sari Bair Offensive (6-10 August 1915). This was an all-or-nothing effort involving the entire MEF including diversionary attacks by French and British troops at Cape Helles and an entirely new landing by four British ‘New Army’ divisions at Suvla Bay seven kilometres north of ANZAC Cove. But the focal point of the offensive was the attempt to seize three key heights along the Sari Bair range (Hill Q, Hill 971 and Chunuk Bair) via a night-time breakout from the ANZAC perimeter by assault columns of New Zealand, Australian and Ghurka troops on 6-7 August. After five days of savage fighting, the British IX Corps was firmly established at Suvla but the all-important high ground from Sari Bair to the Anafarta Hills remained in Ottoman hands. The failed offensive cost the MEF more than 25,000 casualties while the Ottoman losses were just as bad.

What was the role of the ANZACs in the campaign?

The original role of the 30,000-strong ANZAC was to carry out a landing near Gaba Tepe and support the British landings at Cape Helles by advancing inland to capture the Sari Bair Range and Maltepe, thereby cutting the Ottoman lines of communication with their troops at Helles. Instead they were landed at the wrong place – Ari Burnu (ANZAC Cove) – and ended up defending their tiny six kilometre squared beach head for the next three months while the British and French concentrated on trying to break out of Cape Helles. In August the MEF’s attention switched to the ANZAC enclave, which became the focal point of the Sari Bair Offensive in August. The Anzacs played a leading role in this ultimately doomed offensive and suffered accordingly – ANZAC casualties for 6-10 August amount to 12,000. After more heavy fighting in late August to consolidate the link-up between ANZAC and Suvla, the ANZACs settled back into the daily grind of trench warfare to defend their now greatly expanded perimeter until the final evacuation in December.

What technology, weapons and methods of warfare were used by the ANZACs?

The volunteer citizen-soldiers of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) who served at Gallipoli in 1915 had been organised, trained and equipped on the basis of pre-war British Army regulations, albeit with a few local variations in uniform and equipment. Infantry brigades predominated but both expeditionary forces contained a high proportion of mounted infantry regiments (Australian Light Horse and New Zealand Mounted Rifles accordingly). The 25 April landing was an all-infantry affair with the mounted regiments arriving at ANZAC cove as reinforcements on 12 May (without their horses). The infantry and mounted troops from both dominions soon earned a reputation as tough, aggressive fighters who quickly adapted to the conditions of trench warfare on the Peninsula. Their field artillery batteries were equipped with modern 18-pounders and 4.5-inch howitzers, which, somewhat to the ANZACs surprise, made them better equipped than many of the British Territorial or New Army artillery batteries sent out to Gallipoli with obsolescent 15-pounders or worse (although everyone suffered from chronic shortages of artillery shells).

How did the Australian units differ from the New Zealand units?

It was often hard for outsiders to distinguish the soldiers from the two dominions, much to the annoyance of the New Zealanders, who usually found themselves mistaken for Australians as a result (Australia being the bigger country of the two). In 1914-15, the famous ‘Aussie’ slouch hat was actually also standard kit for most New Zealand infantry and mounted units (this changed when the NZEF adopted the ‘lemon squeezer’ felt hat as a deliberate effort to differentiate themselves from the AIF). The New Zealanders also originally used coloured piping on their epaulettes and down their outside trouser seam to indicate arm of service (red for infantry, green for mounted troops, etc). But after a couple of months at Gallipoli such distinctions were all but irrelevant as the men stripped down to shorts, boots and little more to help cope with the summer heat. In demeanour the New Zealanders were often noted as being less boisterous than the Australians and more willing to take prisoners but in terms of fighting ability there was nothing between them.

How did the campaign affect World War I as a whole?

In terms of the war itself the Gallipoli campaign was always a sideshow for Britain and France and so its failure had little long-term impact on the conflict’s outcome, which was ultimately decided on the Western Front. For the Ottoman Empire it was a defensive victory that provided a boost to wartime morale but at a significant cost (total Ottoman casualties for the campaign amount to 190,000) and for negligible strategic gains. On the other hand it’s post-war legacy is much more significant, being the catalyst for the emergence of a distinct sense of national identity in both Australia and New Zealand as well as the modern Republic of Turkey.

The battle is often portrayed as Britain versus Turkey. Were the Germans and French involved and if so, in what capacity?

The Ottoman Army had hosted German military adviser missions for some 30 years leading up to World War I and the Ottoman Fifth Army, responsible for defending Gallipoli, contained a number of German officers on attachment at various levels of command throughout the campaign, most famously it’s commander, General Otto Liman von Sanders. Modern scholarship suggests that the influence and importance of these German officers regarding their Ottoman counterparts has been overplayed somewhat by earlier English language histories of the campaign. Towards the end of the campaign several German and Austro-Hungarian heavy artillery/siege batteries also arrived to bolster the Ottoman forces.

The French contribution to the MEF was the Corps Expéditionnaire d’Orient (CEO), which at its greatest strength totalled some 42,000 men organised into two infantry divisions. Most of these soldiers were colonial troops drawn from garrisons in French North and West Africa. The CEO was involved in the campaign from the 25 April through to the very end, fighting alongside the British VIII Corps at Cape Helles. Approximately 15,000 French soldiers died during the campaign – more than the total of Australian and New Zealand deaths combined (11,400).

The portrayal of ‘Turkey’ as the state the British, French and Anzac troops were confronting is also incredibly misleading. The Ottoman Empire in 1915 was a multi-national empire of some 20 million people of various faiths and ethnicities. The Ottoman Army reflected this diverse reality. Turks dominated the officer corps of the armed forces but the enlisted ranks contained tens of thousands of Arab Muslim conscripts from across the empire, not to mention Kurds, Turkmen and Circassians. There were even non-Muslim conscripts – Armenians, Greeks, etc – albeit mostly in unarmed labour battalions and the like. The Ottoman 19th Division, commanded by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk himself and responsible for almost driving the ANZACs back into the sea on 25 April, was made up of one Turkish regiment and two Arab regiments. Thousands of the ‘Turkish’ dead at Gallipoli were actually Arab subjects of the Ottoman Empire.

Just how did the British hierarchy get so much wrong?

A combination of hubris, wishful thinking and a naive, almost amateur approach to the conduct of military operations. The catalogue of incompetence that marred the campaign from beginning almost to the end (the evacuations were the only large-scale operation mounted by the MEF to succeed) became a public scandal even as it was unfolding thanks to the efforts of Australian war correspondent Keith Murdoch, and contributed to the downfall of the Asquith government and its replacement by a coalition under Lloyd George. The Dardanelles Commission was established by an act of parliament in 1916 specifically to investigate the failings of the Gallipoli campaign.

Did it affect the way the British began new campaigns in the future?

Yes. Coupled with the disaster at Kut in early 1916 Gallipoli became a poignant lesson for British politicians and generals alike in how not to conduct a military campaign. Admittedly the rest of the British Army, including the BEF, were still in the early stages of a steep and costly learning curve in 1915 but the quality of British and dominion military staff work and attention to planning, especially in regard to logistical issues, would soon reach a level of professionalism and competency that made a repeat of Gallipoli unimaginable in the later years of the war.

Was there an alternative operation possible? Could it ever have worked?

Even if the original naval attack or the later invasion of the peninsula by the MEF had succeeded in eliminating or neutralising the Ottoman coastal defences and blocking the Dardanelles Strait, it seems the height of folly to expect that the Ottoman government would surrender if an Anglo-French fleet reached Constantinople. Given the size and geo-strategic depth of the Ottoman Empire, surely it was just as likely that the Ottoman government would simply relocate to another Ottoman city deep in the heart of Anatolia or somewhere similar and carry on fighting?

What would have happened if there was no Gallipoli?

In terms of World War I as a whole it would probably have made little difference given the obsession of the Ottoman Empire’s wartime leader, Enver Pasha, with fighting the Russians and advancing the cause of pan-Turkism deep into the heart of Central Asia. The remaining Ottoman reserves would still have been squandered on his quixotic invasion of the Caucasus in 1918. As for its post-war legacy in Australia and New Zealand, chances are the nascent nationalism born at Gallipoli would simply have emerged on a battlefield in Flanders or Picardy, a la the Canadians at Vimy Ridge, instead of Gallipoli. The implications for the rise of the modern Republic of Turkey are much more difficult to tease out.

What did both the Entente and the Central Powers learn from Gallipoli?

Enthusiasm and a ‘muddle through’ approach to complicated military operations conducted at the extreme edge of your lines of communications deep in the heart of enemy territory are no match for a thorough, and at times ruthless, professional approach to planning, preparation and execution. More specifically, the British (and the ANZACs) learned that far from being a spent power the Ottoman Army could still be a skilled and tenacious opponent, and one you underestimated at your peril.