Up until the counterinsurgency in Afghanistan, the Vietnam War was the longest armed conflict involving the USA. It remains a complex and misunderstood conflict, framed for many by a succession of arguably misleading (albeit entertaining) Hollywood movies.

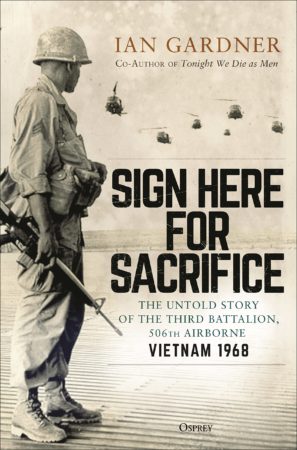

In his new book Sign Here for Sacrifice, author and historian Ian Gardner focuses on the story of one battalion, an outfit with the prestigious legacy of the 101st Airborne to live up to. Gardner describes how the 3rd Battalion, 506th Airborne (3/506) was formed from volunteers, and put through rigorous training before shipping out to take on the Viet Cong in the unrelenting jungles on the frontline.

A former Para himself, Gardner recounts the 3/506’s first ‘Search and Destroy’ missions, as the battlefield tactics and military theory of veterans such as the inimitable Lt. Col. John Geraci was put to the test. Here Gardner discusses his new book and what drew him to the story of the 3/506.

What initially interested you in the story of the 3rd Battalion, 506th Airborne?

The enigma surrounding airborne soldiering has always been of deep interest for me. Growing up near Aldershot in Hampshire, we often saw recruits from Browning Barracks or Depot Para wearing their camouflage peak caps, being tested to the limit either in training or on Pre-Parachute Selection known as P Company. This fascination continued to grow until eventually I stepped up and qualified as a reserve paratrooper in 1988.

Some years after leaving Support Company, 10 Para, I discovered the book “101st Airborne at Normandy” by Mark Bando and kept coming back to Chapter 21 “The Bridges at Brévands” – main objectives of 3/506 on D-Day. Unlike all the other chapters, this section was short, sketchy and as it turned out, a little inaccurate, but nevertheless what Mark had recorded was tantalising and I was hooked.

This fabulous publication and my subsequent meeting and writing partnership with Roger Day all contributed to the creation of our seminal bestseller “Tonight We Die as Men.” It is fair to say that Mark and moreover Roger were my gateway guides into the world of 3/506 and their contribution to WWII.

Some two decades and four solo books later with my written work now firmly planted on the global history map, a friend encouraged me to consider the battalion’s re-birth in April 1967 and so eventually “Sign Here For Sacrifice” became the culmination of everything that had gone before. At first I was not confident that the correct apparatus was in place to achieve my vision but after C Company veteran Sergeant Mike Krawczyk rallied to the cause we never looked back.

Many discussions followed as Mike gathered over thirty “boat troopers” and instilled them with confidence in my ability to get the job done and how important this story was going to be for everyone concerned including me. By the way, “Boat Trooper” was the title adopted by these original volunteers and spotlighted their three-week sea voyage to Vietnam. All of that aside, it did not take long for me to recognise the synergy between the two eras as I threw myself into bringing this inspiring tale of service and duty back to life.

© Ian Gardner / Osprey Publishing

How important was the prestige, or daresay ‘legend’, of the 101st Airborne name, to 3/506? Was it good for morale, for instance?

As a Division, the weight of legacy has been proudly bestowed and worn on every shoulder since WW2. But beyond this obvious iconography the Vietnam era 3/506 rallied around another important name – “Currahee.” “Currahee” was no accidental happenstance but a direct homage to legendary Colonel Robert F. Sink’s original “Native American” regimental motto meaning “stands alone” which was also adopted by Geraci.

Mount Currahee was the Appalachian mountain in Georgia that dominated Camp Toccoa – birthplace of Sink’s 506 Parachute Infantry Regiment. This term was dusted off and absorbed by Lieutenant Colonel John Geraci who clearly understood that it would define his latest generation warriors. First Brigade had already been in Vietnam since 1965 under leadership of Brigadier General Salve Matheson who had been a highly valued member of Sink’s staff during World War Two. In part 3/506 was Matheson’s brainchild and choice of leadership, training and preparation were all essential components for his new Manoeuvre Battalion. Geraci quickly reintroduced the circular vintage “para-dice” patch and had it sewn onto the battalion’s purple PT shorts in replication of the Sink generation. In further homage, John also commissioned a battalion prayer that named Third Battalion’s last two casualties of WW2.

As Second and Third Brigades were not yet on alert for Vietnam, it made Geraci’s outfit a far more attractive proposition for the young paratroopers. This opportunity to serve with a bespoke unit also appealed to those now seemingly stuck in limbo at Fort Campbell. Many had also been recently inspired by the 173rd Airborne Brigade, who jumped into battle north of Saigon at the beginning of Operation Junction City. It was fair to say that morale was stratospheric as the faithful of 67 could not wait to get into the fight and 3/506 with its bespoke proposed parachute role and obvious historical back-story became their conduit and savour for action.

The difference between the Airborne forces of WW2 and Vietnam are perhaps more stark than their similarities – not least with the primacy of helicopters – but what main similarities do you see between the two eras?

Obviously things had changed since 1945 but that independent volunteer spirit was abundant and although the guys were now multi-racial their sense of brotherhood, loyalty and duty still remained the same. Likewise the physical challenges for airborne selection and parachute training had not really changed either. Senior NCOs and Cadre were still handpicked in the same fashion but unlike ‘42, most had already served at least one previous tour in Korea or Vietnam or both. However, US Army basic infantry preparation was now longer with every potential airborne recruit having gone through eight weeks “Basic” followed by another eight weeks of “Advanced” before volunteering for three-weeks at jump school.

Some might argue that in 1942, the experimental “A” Stage, specifically created by Sink was a tougher deal but I do not believe that is necessarily true. Designed to select and mould raw civilian volunteers into high value shock troops, the entire fifteen-week course also included jump school as its final process. Back in the day, after gaining their wings the successful candidates went on to take part in several large field problems before being “officially” attached to the 101st Airborne Division and dispatched to England. In comparison, John Geraci’s men were already fully trained with plenty of previous in-house divisional experience when they began filtering into the re-activated battalion.

© Ian Gardner / Osprey Publishing

Like their WW2 counterparts, the men took part in several ultra long distance battle marches and parachute drops as over the next five-months each was conditioned for their upcoming role in Vietnam. Upon arrival in Phan Rang everyone enrolled into two weeks Proficiency Training to bring them up to speed with the latest operational attentions and details. Ironically, the only thing neglected by the syllabus was quality continuation training for inner city urban warfare.

This turned out to be an oversight especially when heavily entrenched VC forces had to be cleared from Phan Thiet during Tet. After Phan Rang most officers and top tier NCOs were sent up north for a week of OJT or “on the job” training. Here the guys participated in active combat patrols with their counterparts in First Brigade. The term “shock troops” could still be levied as Third Battalion was deployed to stop an insurgent war in the jungles, rice paddies and mountains and this style of mission execution was worlds apart from the fighting experienced in Europe during WW2.

Small and large scale Search & Destroy Operations were now the name of the game all initiated by helicopter insertion known as “Combat Assaults.” However, General William Westmoreland’s promise of a battalion combat drop was still open and the men were enthusiastically looking forward to their own D-Day challenge. Thankfully when that moment came, the jump was “scrubbed” just as the guys walked out onto the tarmac.

As a former Para yourself, what similarities and differences do you see between the way the 3/506 trained and operated with your own training? Is there a common experience and shared traits between paratroopers?

Although I was a member of a Territorial Army Battalion the guts and drive required to become a paratrooper and wear “the badge of courage” was still exactly the same. In my experience P Company was and perhaps still is a runner’s course that required cool controlled aggression, stamina and a good amount of barrack room humour. During the cold wet winter of 1987, I was running a marathon in under three hours and had the Training Area on my doorstep. Before joining 10 Para, I tackled the tough “Ten Mile” P Co course every Saturday morning carrying 37.5lbs of equipment for nearly four months.

Always pushing myself, the ability to go above and beyond is a common mentality found in people like me, who, every step of the way, earned their place on the aircraft through blood and sweat. Being “beasted” by the Directing Staff was something everyone had to endure but if you could hold your own, they pretty much left you alone.

I loved P Co but it was only down to fitness and good preparation that made the process so enjoyable, well at least for me. I know this feeling is shared and relished by every single one of my contributors, who were also volunteers in search of a new challenge. The ideals and experiences we absorbed back then shaped us into the breed of humans we are today with our own set of unusual terminologies and positive can do attitude.

© Ian Gardner / Osprey Publishing

Before serving in Vietnam, 3/506’s (later Colonel) John Geraci had already served in WWII and the Korean War. Was this vast experience typical or unique for officers in the US Army in Vietnam?

For the old sweats this was not necessarily unusual although in John’s case his career spanning three wars and four Silver Stars did have many unexpected twists and turns. The colonel was a larger than life character who inspired the same response from his soldiers. I would like to point out that John was from a working class Italian family and had not been to West Point or any of the other prestigious Military Academies but joined the Marine Corps on his 18th birthday as a Private First Class. After the war to end all wars, he went back to college and studied English and Philosophy, while earning extra money as a door-to-door salesman.

On New Year’s Day 1949, then an Army reservist, John was called up to attend Officer Candidate School before being sent to Korea where he won his first two Silver Stars for Bravery. However, Vietnam would become John’s most significant experience of conflict and this is where things get interesting. During his first tour in 1960, with the Military Assistance Advisory Group, Geraci’s ability to speak several languages, especially French, proved invaluable. Promotion to lieutenant colonel soon followed, along with a staff appointment to the Joint Unconventional Warfare Task Force.

A second tour in ’63 brought him into close contact with Major General Duong Van Minh, who at that time was open to the possibilities of regime change. In my opinion this kind of political awareness elevated Geraci to a somewhat unique level but more importantly proved to be a valuable asset when later dealing with the class conscious and petulant South Vietnamese Army.

In the early 1960s, the small numbers (relative to later) of US troops deployed in VN managed to gain experience of the nature of the war developing there. How and to what extent did this experience help to prepare the vast numbers of troops deployed later in the Sixties?

As previously mentioned, John Geraci had been among 385 personnel sent in 1960 to bolster the Military Advisory and Assistance Group who had been active in Vietnam for nearly five years. However, before taking command of A-3/506, Thomas Gaffney’s earlier covert service perfectly illustrates your question. Tom had previously served three tours with Special Forces in Laos providing training against communist Pathet-Lao insurgents for the Laotian Airborne and indigenous Mountain Guerrilla Forces.

Captain Gaffney brought a big slice of this experience to Third Battalion, and was the reason why Geraci went so far out of his way to bring his old friend on board. At 37-years-old Gaffney was regarded as an elder statesman by young West Pointers, Bill Landgraf and Nick Nahas, who had been selected to lead Bravo and Charlie companies. Always on hand with advice and criticism, Tom played an essential role in their growth and general awareness of organisations such as the CIA. You can be certain that many like Geraci and Gaffney (who passed away in December) who made up MAAG and SF in those early days went on to fill important combat command roles in the years that followed. I can only speak for the people I know but in my opinion this level of knowledge was absolutely invaluable as it inevitably filtered down to those who signed on in 1967.

© Ian Gardner / Osprey Publishing

Combat patrolling was a major part of 3/506’s role, and the US infantry in general – how was this tactic developed by the US and how effective was it on the ground?

In my humble opinion the helicopter insertions developed by General Westmoreland were an essential component to counter insurgent disruption. But were there enough men available to carry out those long silent gruelling deadly Search & Destroy missions? Of the half a million US personnel who were in Vietnam by ‘68 only around fifteen percent were actually destined for battle.

It was a proven fact that multiple patrolling deterred attacks and forced the enemy to migrate into open areas where artillery and air power could be more effectively used against them. This could be scaled up or down depending on task and opposing troop strength. The VC suffered a number of hefty defeats during Tet and many defected under an “open arms” policy known as Chieu Hoi. Predominantly these individuals became scouts and led American infantryman back to thousands of remote hidden camps, booby traps, caches of weapons, medicine and food.

However, for many reasons ongoing home support was rapidly dwindling owing to a negative groundswell in reporting rhetoric from influential American media outlets that naively argued the Tet Offensive was a political victory for Ho Chi Minh! But despite this sudden confusion on how to move forward, in places such as the Central Highlands, America’s only way to actively engage was on foot by gut busting exhaustive S&D supported by cloverleaf and pinwheel ambushes.

Apart from Congress and The White House, the real enemy on patrol was still heat exhaustion and no matter how much fluid an individual carried it was never enough. Of course natural water was readily available but it always came with risk of dysentery and other diseases. Personal hygiene was almost impossible but to prevent rusting and cycling issues, all weapons had to be maintained and oiled at least twice a day. Many NCO’s developed their own preferred patrolling methods that were not necessarily “by the book” especially when it came to ambush techniques.

For example Edward Bassista from A Company regularly placed double the “official” requirement of claymore anti-personnel mines around his position. Once triggered, Ed would have his squad hold fire and wait. When he was satisfied all was clear, Sergeant Bassista advanced alone to methodically finish off any wounded with their own weapons. It was a personal tactic that really worked and caused utter confusion to any insurgent squad unlucky enough to enter Ed’s kill zone. Simplified, this war demanded instant decisions to unconventional questions and no doubt the US Search & Destroy ethos was working. However, this success in my opinion was undermined by the South Vietnamese Army’s overall failure to pacify its own civilian population.

© Ian Gardner / Osprey Publishing

You mention how the 3/506 was re-designated ‘airmobile’ as opposed to ‘airborne’ – does this reflect the dwindling primacy of trained parachutists in Vietnam, in particular, or in warfare more generally?

I do not pretend to be an expert here but it occurs to me that the value and appeal of mass parachute insertion did reduce significantly especially after General William Westmoreland (who was a great advocate for all things airborne) lost his command of MACV during summer of ’68.

When merged into a Task Force, although still on stand by, Third Battalion’s opportunities of a future combat jump were pretty much reduced to zero. Scrolling forward fifty years, compared to the UK, America still has a huge amount of parachute trained personnel although I believe many of these soldiers are not actually “in date.” It could be argued that use of paratroops in modern warfare is outdated but to me the most important thing here is keeping the esprit de corps and spearhead readiness that our airborne forces bring to emergency or trouble spots anywhere in the world.

Did you speak personally with many veterans of 3/506 in the making of this book? What was your impression of their feelings about the war, looking back?

From the very first chapter I set out to make sure that every reader became fully invested in our main contributors. The story is told through honest, passionate and easy prose that I feel mark a positive turning point in my writing. Relief, regret, validation, recognition…the interview process was a revelation on many levels. A number of the guys have now become close friends and no doubt will continue to be so for many years to come. Many expressed feelings of frustration and relief and were proud that their very own “Band of Brothers” story was after more than fifty-years finally being offered up to the world. Everyone to a man still mourned lost friends (whose stories we also follow) and wished perhaps that they could have done something more to save them. There was still so much love and respect floating around between the survivors, who are a rare breed and getting rarer year on year.

Sign Here For Sacrifice is available now from Osprey Publishing