In the mid 19th century, as the burgeoning United States pushed its borders ever further west and south, it inevitably came into conflict with its neighbour, Mexico. This expansionist war of 1846-48 saw the US grab huge swathes of land, including California, and left Mexico deep in debt to Britain, France and Spain, who had all helped to fund the country’s military. A civil conflict – the Mexican Reform War – followed, further crippling the country’s economy.

“In early 1862, a French force of some 6,000 men successfully invaded Mexico, led by General Charles de Lorencez”

When the war ended in 1861, Mexico’s new president, Benito Juárez, took the bold decision to cease interest payments on its European loans. Both Britain and Spain were aggrieved enough to send token military forces in an attempt to put the squeeze on Juárez, but France took it one step further and sought to occupy the country.

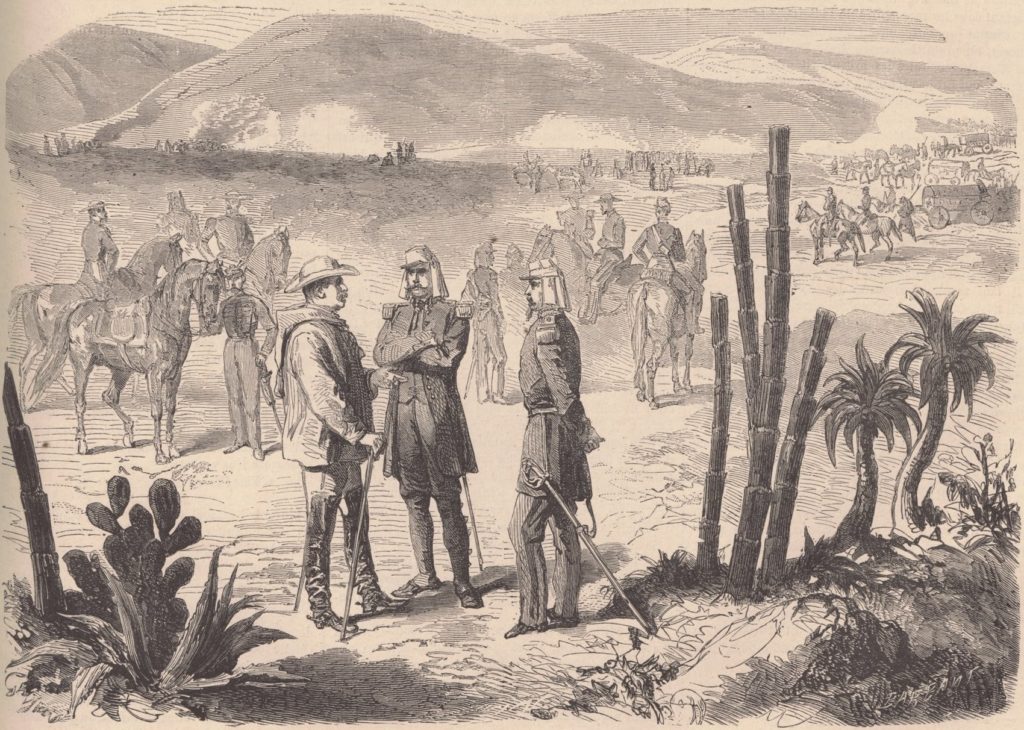

In early 1862, a French force of some 6,000 men successfully invaded Mexico, led by General Charles de Lorencez. It landed on the east coast at Campeche, and headed inland to seize the capital, Mexico City. It was a bold plan but de Lorencez was confident of success. After all he was leading highly trained, well-equipped European troops against a peasant army that would – on paper at least – be no match for his modern force. But he was in for a rude awakening.

On 5 May, de Lorencez’s army made camp on the outskirts of Puebla, 129 kilometres northeast of Mexico City. Mexican officials were desperately trying to negotiate a French withdrawal from the country but with little success. As discussions faltered, Lorencez decided to attack two Mexican forts under the command of General Ignacio Zaragoza, which overlooked Puebla’s northern outskirts.

“On 9 May 1862 the president declared that henceforth Cinco de Mayo (5 May) would be a recognised public holiday”

The Mexican Republic had recently annexed the town, and de Lorencez assumed its citizens would help to overwhelm the 2,000-strong garrison that policed them. He was wrong. The attack began just before noon with an artillery salvo followed by an infantry assault. The attack failed.

De Lorencez ordered a further artillery bombardment and another infantry assault, but that was also repelled. By 3pm, with his artillery now out of ammunition, he ordered his infantry to make a final and – as it transpired – disastrous attack. Torrential rain now began to lash down turning the battlefield into a quagmire. As the French retreated through the mud for the last time, Zaragoza had his cavalry chase them down. By the time the fighting was over, the Mexican garrison had suffered 83 dead and 131 wounded, but their lines still held.

“The Battle of Puebla marks the last time that a country in the Americas was invaded by a European force”

The French force, by comparison, had been devastated – 462 soldiers lay dead on the battlefield, while more than 300 others had been wounded. De Lorencez now withdrew what remained of his forces to Orizaba, 145 kilometres to the east to regroup.

The defeat of the French at the Battle of Puebla proved an inspirational event for the young Mexican Republic, and on 9 May 1862 the president declared that henceforth Cinco de Mayo (5 May) would be a recognised public holiday. To this day it is still celebrated in the United States, often erroneously as Mexican Independence Day. Perhaps more importantly, however, although the war against the French would eventually end in defeat, the Battle of Puebla marks the last time that a country in the Americas was invaded by a European force.

This article originally appeared in All About History issue 51

Subscribe to All About History today for amazing savings!