Oliver Cromwell founded the New Model Army, a revolutionary force that won the British Civil Wars and destroyed a king

Subscribe to History of War now for amazing savings!

In the 1640s, people of all classes were embroiled in a grim struggle over a fundamental question – who was the supreme power in the land, the king or Parliament? The British Civil Wars raged for a decade and became a cataclysmic struggle for England’s soul. It was also a conflict that would engulf Wales, Scotland and Ireland with devastating consequences. The resulting chaos saw the execution of a king and the establishment of a republican Commonwealth. Two factors were largely responsible for making this radical change possible. One was an obscurely born MP from Huntingdon called Oliver Cromwell; the other was the most innovative military force of the age – the New Model Army.

The “Ironsides”

When Charles I declared war on 22 August 1642, the Royalist and Parliamentarian armies were evenly matched – both amateur in attitude and performance, particularly regarding their commanders. On the Royalist side, Prince Rupert of the Rhine was an experienced soldier but he was also hot-headed and unable to control the cavalry under his command. During the first major battle of the war at Edgehill on 23 October 1642, the Royalists nearly won when they broke through the Parliamentarian lines with a cavalry charge. However, this breakthrough was not properly followed up as Rupert’s cavalrymen charged away from the battlefield to loot nearby villages – the end result was stalemate.

Similarly, Parliamentarian forces were at first commanded by ineffectual aristocrats such as the earls of Essex and Manchester, whose field strategy was timid and lethargic. This meant that there was no decisive battle for the first two years of the war. Oliver Cromwell observed these circumstances from the sidelines with frustration, and resolved to change the situation to Parliament’s advantage.

Already in his forties when the war broke out, and without any military training, Cromwell was an unexpected innovator who was determined to reorganise Parliament’s army. His personal strength stemmed from his religious fervour. Cromwell was a religious zealot who saw the hand of God in everything and this enabled him to be a supremely confident commander who was willing to take risks. In 1643, he formed his own cavalry regiment in Huntingdon, which was initially known as the ‘Army of the Eastern Association’ but was remembered by history as the ‘Ironsides’.

This force was at first composed of determined Puritan farmers who were deliberately chosen for their strict religious resolve. Cromwell’s training of his Ironsides made him stand out against other commanders, particularly his Royalist counterparts. He followed the common practice of arranging his cavalry in three ranks, while leading them forward for impact rather than firepower. However, he also encouraged his troops to charge in close formation while riding knee-to-knee. This was a tactic already familiar in Europe, but it was entirely new to English shores. Cromwell quickly became an ambitious professional soldier and his Ironsides were an asset on the battlefield.

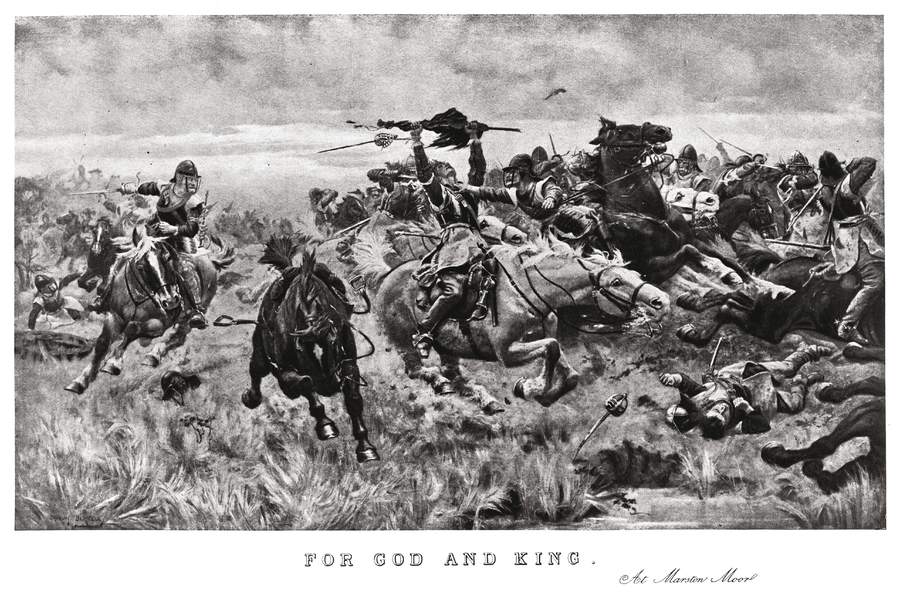

Cromwell’s cavalry played a notable part in the Parliamentarian victory at the Battle of Marston Moor on 2 July 1644. Unlike their Royalist counterparts, the Ironsides stayed on the battlefield after their initial charge and attacked the Royalist infantry. This show of discipline secured the north of England for Parliament and sealed Cromwell’s reputation.

Nonetheless, the army was still commanded by incompetent nobles who did not follow up Marston Moor with similar victories, much to Cromwell’s frustration. After Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester failed to chase Charles I to Bath at the Second Battle of Newbury, Cromwell decided that the existing commanders had to be replaced by professionals. He was not alone in this view and another Roundhead commander, Sir William Waller, wrote to Parliament stating: “Till you have an army merely your own that you may command, it is in a manner impossible to do anything of importance.”

In early 1645, the ‘New Model Ordinance’ was passed, which encompassed a total reorganisation of Parliament’s army. This new force was to have 22,000 men in which there would be 12 regiments of foot with 1,200 men in each section. Each regiment would contain two-thirds musketeers and one-third pikemen. Additionally, there would be 11 cavalry regiments, one regiment of dragoons and an artillery train of 50 guns. The highly experienced Sir Thomas Fairfax would command the army and Philip Skippon the infantry.

In April 1645, Cromwell forced through the ‘Self-Denying Ordinance’ bill, preventing MPs in the House of Lords and Commons from holding military positions. Essex and Manchester resigned, but Cromwell, as MP for Cambridge, was considered too important and kept his command. Fairfax made Cromwell the commander of the cavalry, with the Ironsides forming the nucleus of Parliament’s force. The New Model Army was born.

“Godly” Redcoats

Cromwell and Fairfax quickly developed the New Model Army into an efficient force. In a unique move for the period, officers were appointed and promoted on merit rather than social standing. For example, Colonel Thomas Pride was a former brewer and many other officers came from humble backgrounds. Discipline was strictly enforced but soldiers were compensated with regular pay. Infantrymen were paid eight pence a day while the cavalry received two shillings, as they had to supply their own horses and pay for their upkeep.

Parliament’s army would also look highly distinctive. In the early years of the Civil Wars, specific regiments on both sides wore coloured uniforms such as the Royalist ‘Whitecoats’ and ‘Bluecoats’. However, there were no specific colours for whole armies and it could be very difficult to tell apart comrades from enemies in the middle of a battle.

Cromwell concluded that soldiers’ equipment had to be standardised, including their clothing. Venetian Red was chosen as the colour of the official uniform as it was the cheapest dye available. This inexpensive quality matched the Puritan ethic of unassuming modesty and the tone of the original redcoats was not plush scarlet but a muddy reddish-brown. The introduction of the redcoat seems to have had a positive effect on the troops and it promoted solidarity among it’s low-born but capable soldiers.

In addition, the New Model’s structure was highly organised. Officers undertook specific duties, such as the administration of justice and the acquisition of supplies. These tasks were performed nationally and under a unified command. By contrast, the Royalists were hindered by factional infighting at Charles I’s court in Oxford, where key decisions often ended in confused squabbling.

Key to the strength of the New Model Army was its highly religious outlook. Cromwell believed that military victory was the outcome of God’s will. He wanted the army to “valiantly fight the Lord’s battle” as “an army of saints”. To that end, recruits were drilled using a book called The Soldier’s Catechism. This instilled the troops with a sense of divine mission. One of the first questions in the book asked: “What are the principal things required of a soldier?” The answer was, “That he be religious and Godly.”

The men were vigorously encouraged to be honest, principled, politically motivated and sober. They were fed propaganda that the Royalists were the complete opposite in their behaviour and were described as arrogant, drunk and pretentious. This was an army that stood apart from others in that it was specifically designed to aid a modern political and religious movement.

The term ‘New Model’ was apt because nothing like it had been seen before. The pious passions of its soldiers would be the deciding factor in the outcome of the Civil War and Cromwell himself proudly remarked on his redcoated troops, “I had rather a plain russet-coated captain that knows what he fights for and loves what he knows, than that which you call a gentleman, and is nothing else. I honour a gentleman that is so indeed.”

Naseby

Within months of its creation, Parliament’s army gained its first major victory at Naseby on 14 June 1645. This battle showed the difference in discipline between the Royalists and Parliamentarians. Fairfax was the overall commander, but it was Cromwell’s Ironsides who again tipped the balance in Parliament’s favour.

After breaking many of the Roundhead horsemen, Prince Rupert could not prevent his cavalry from diverting away from the main battle in order to attack the Parliamentarian baggage train. This repeat blunder, which was reminiscent of Edgehill, contributed to the Royalist defeat. However, what was more essential to the Parliamentarian victory was Cromwell’s disciplined command of his own cavalry. Forbidden to leave the battlefield, the Ironsides instead smashed the Royalist centre before Rupert’s cavalry returned and then remained on the field to consolidate their position. When Rupert eventually rallied his troops to return to the battlefield, they refused to attack the Ironsides.

Naseby was a decisive triumph. Charles I’s army was shattered and all of it’s artillery and stores were captured. The New Model Army’s superiority was confirmed. Before Naseby, the Royalists had mockingly referred to Parliament’s reorganised force as ‘The New Noddle’. Now they could no longer hope to win the war.

Within a year, Charles surrendered and the First Civil War was won for Parliament, thanks largely to the strength and effectiveness of the New Model Army. However, Parliament’s victory did not end the conflict. In a sense, the New Model Army won its spurs at Naseby, but it would face many more battles in the coming years. It was these encounters that confirmed the army’s reputation as the era’s pre-eminent fighting force.

Preston

After Charles I’s surrender, there was an extended period where Parliament, the army and the Scots struggled to reach an agreement on how to settle the kingdom. Although Charles was a prisoner, he was also considered crucial to the proceedings. The king was uncooperative and secretly negotiated with the Scots to invade England on his behalf. This sparked another civil war and a Scottish army crossed the border in July 1648. After a month of skirmishes, Cromwell marched north.

The two armies met outside Preston in mid-August. Parliament’s army had to fight a large Scottish force of nearly 20,000 men, commanded by the duke of Hamilton. By contrast, Cromwell only had 9,000 troops, and of those just 6,500 were experienced soldiers. Despite this, Cromwell’s force was much more disciplined than the Scots, who were also spread out over 20 miles around Preston. This meant that Hamilton couldn’t communicate properly with his troops. The Scottish commander had placed his cavalry in the vanguard, while his infantry was left trailing behind traversing over boggy ground, which hampered their speed. Cromwell saw these advantages, and on 17 August, he attacked the infantry in the rear of Hamilton’s army. However, the boggy ground restricted the New Model Army’s movement, particularly as it was reliant on the Ironsides for success. This left a brutal and bloody struggle for control of Preston, as Cromwell’s troops clashed with the Scottish infantry.

At the end of the day, the fighting had cost the Scots 8,000 killed or captured. One action at the Ribble Bridge had seen hard fighting lasting more than two hours, but the battle was not yet won and it continued the following day. Cromwell had to invest Preston with a strong garrison and guards for the large number of prisoners. He only had 3,000 infantry and 2,500 cavalry to fight the remaining 10,000 Scottish troops. Luckily for the English, Hamilton was experiencing his own problems – his men were exhausted, lumbered with wet ammunition, and many of the hungriest had gone to Wigan to plunder food. This enabled Cromwell to continually harry the Scots as they fought a disorganised retreat. Despite making some determined stands at various passes and bridges, Hamilton’s army could not withstand the disciplined onslaughts from the Ironsides, and eventually what was left of the troops offered their surrender.

Regicide and the Irish Campaign

Once again the New Model Army had flattened Royalist hopes of victory, and this time Parliament no longer accommodated the king. He was put on trial for treason against his own people, found guilty and publicly beheaded at Whitehall on 30 January 1649. Cromwell was one of the signatories to his execution and England was declared a republican Commonwealth with the New Model Army acting as the enforcer of this new state. Fairfax resigned his army command in protest against the king’s death and Cromwell became commander-in-chief of the army.

Many others were also outraged by Charles’s execution, particularly the Royalists and the Scots who had not been consulted about their monarch’s fate. This anger found an outlet in Ireland, where English Royalists formed an alliance with Irish Catholic Confederates and Ulster Scots against the Commonwealth. Therefore, in March 1649, Parliament commissioned Cromwell to invade Ireland with the New Model Army. Leaving nothing to chance, he made sure the men, including some 12,000 veterans, were fully paid and equipped before setting sail.

His Irish campaign would be of a different nature to the ones that came before and after. Instead of decisive battles, the army would engage in a series of sieges that would whittle down Irish resistance. For Cromwell, it would be a militarily brilliant campaign, but also one marred by controversy. His tactics centred around massive artillery bombardments of fortified towns and speedy marches to surprise neighbouring garrisons. To save time and men, he would issue generous surrender terms, but if a garrison refused to comply, he used shock tactics to persuade others that capitulation was the best option against the advancing force. The most notorious of these incidents occurred at the Sieges of Drogheda and Wexford, although both of these were notable military successes for Cromwell.

At Drogheda, artillery was used to concentrate firepower into the breaches and Cromwell personally rallied his troops by leading them into the fray. Parliamentarian casualties were low, numbering about 150 men. Similarly at Wexford, Cromwell skilfully manoeuvred around the port and approached it from the south. This took the garrison by surprise as they were expecting the army to approach from the north. The town was quickly taken and the army captured ships, artillery, ammunition and tonnes of supplies. Once again, losses were very low with casualties of 20-30 men.

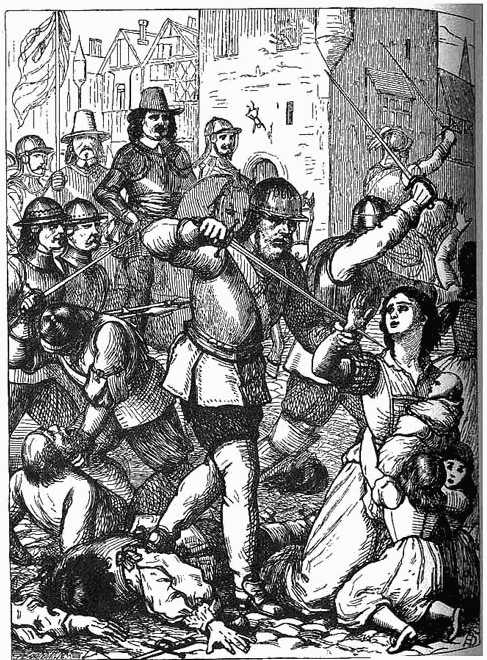

What tarnished these successes were the massacres of enemy soldiers and civilians. During the storming of Drogheda, about 3-4,000 soldiers and civilians were killed, many of them in cold blood. Likewise at Wexford, a similar number of Irish soldiers and civilians were killed. In both sieges, the massacres occurred when New Model Army troops went on a frenzied rampage after the towns were stormed. In 17th-century Europe atrocities such as this were tragically common. However, horrific though the massacres were, they did serve a purpose. Many Irish towns subsequently surrendered to Cromwell out of fear, not just of the New Model Army’s military prowess but also to prevent further loss of life. This saved Cromwell time and supplies in conducting drawn-out sieges.

He also showed strategic foresight over the following winter in 1649-50. The season was unusually mild and the army used this to procure supplies of fodder for its horses and draught animals. This allowed Cromwell to renew operations at the end of January 1650, rather than having to wait for the spring. Despite the seemingly unstoppable force of the New Model Army in Ireland, it was also the only place where it suffered a serious beating.

At the Siege of Clonmel in May 1650, Cromwell attempted his usual tactic of storming the town after an artillery bombardment. However, unknown to the army, the breach was internally surrounded with an enclosed area that was filled with Irish cannon and musketeers. Two assaults by the New Model Army ended in disaster. On both occasions, the English became trapped and eventually an estimated 1,500-2,500 soldiers were killed. This was the army’s first major setback and its greatest loss of life sustained in a single action. Nonetheless, the Irish had also suffered and abandoned the town having lost several hundred men. Cromwell left Ireland soon afterwards but his remaining troops carried on the systematic conquest of the country, with the whole island eventually being subjugated.

Dunbar

After returning from Ireland, Cromwell invaded Scotland with a veteran army of 15,000 men (10,000 foot and 5,000 horse) to pre-empt an invasion of England by Charles II, Charles I’s eldest son and heir, who had been proclaimed as king of Scots. Although many Scots had been his allies in previous campaigns, Cromwell implored the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland to reconsider their decision, “I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken”. The Scots rebuffed his entreaties to renounce Charles II and Cromwell decided to invade Scotland to enforce his will.

As the campaign got underway, the Parliamentarian army was supplied from the sea on the east coast of Scotland because the Scots had adopted a scorched-earth policy between Edinburgh and the border. By September 1650, the fatigued New Model Army started to retire to their supply base at Dunbar. However, the Scots got there first and blocked their path by positioning themselves on Doon Hill, which overlooked the Berwick road. This was the only route back to England and the Scots were also numerically superior with some 22,000 men and fighting on home territory.

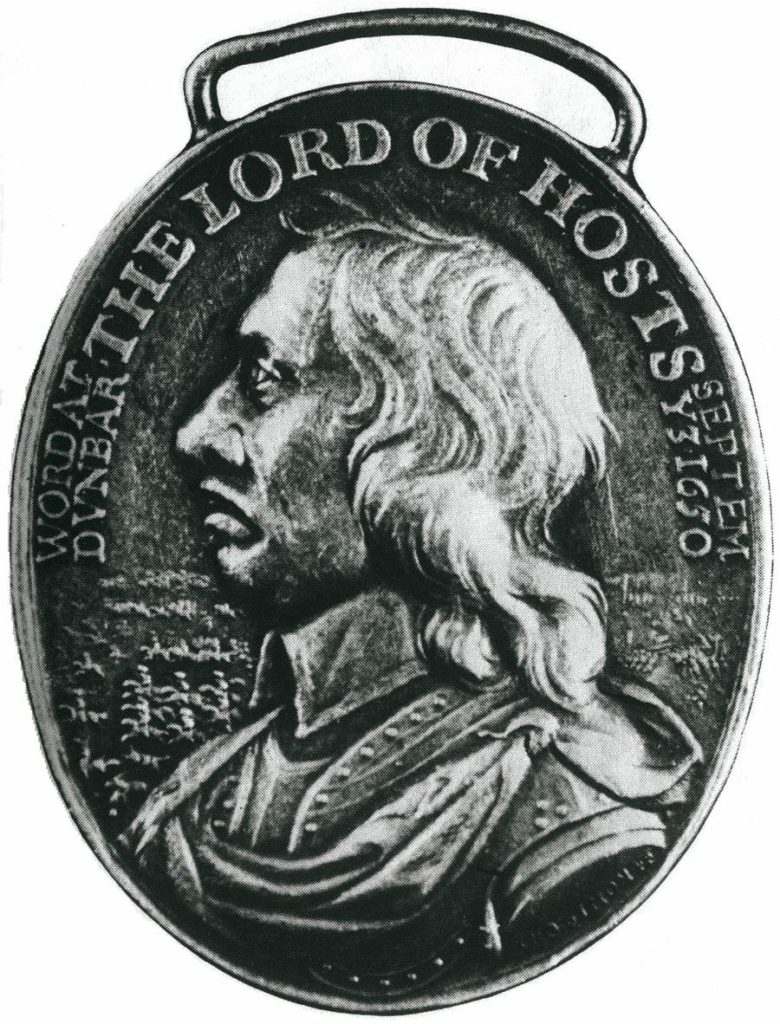

With some of his men suffering from illness, Cromwell was outnumbered almost two to one and with battle now the only option, even he acknowledged that the situation had turned desperate: “We are upon an engagement very difficult… the enemy hath blocked up our way… through which we cannot get without almost a miracle.” To add to Cromwell’s misery, the Scots were commanded by David Leslie, a highly experienced soldier. Leslie and Cromwell had fought together at Marston Moor where the former had played an important part in the Parliamentarian victory. However, on 2 September, under pressure from the Scottish Kirk and Parliament to attack, Leslie moved down from his commanding position on Doon Hill towards Dunbar to launch an attack on the English encampment. Cromwell immediately saw this mistake and decided to meet the challenge the next day on 3 September 1650.

Cromwell attacked at dawn and assaulted the Scottish right flank in a surprise cavalry charge with the English shouting their battle cry, “The Lord of Hosts!” Meanwhile, Major-General George Monck struck the Scottish centre with his infantry. Throughout this initial engagement discipline remained vital. Having swept the Scottish right cavalry from the field, Cromwell and Major-General John Lambert regrouped their cavalry while Colonel Thomas Pride’s infantry fought against the Scottish centre. As they prepared for the next stage of the battle, the English cavalry sing the 117th Psalm in an attempt to boost morale.

While Pride slugged it out in the centre, Cromwell relaunched his cavalry to charge the rear of the Scottish infantry. Pride’s infantry surged forward and the Scots’ position collapsed. Leslie’s army retreated west and then north, which left the New Model Army unexpectedly triumphant. 4,000 Scottish soldiers had been killed and 10,000 taken prisoner for only 20 dead Englishmen in what came to be regarded as Cromwell’s greatest victory. He later described Dunbar as “…one of the most signal mercies God hath done for England and His people” and with the Scottish army now destroyed he was able to capture Edinburgh.

Worcester

Despite the Scots catastrophic defeat and after many negotiations, Charles II sailed to Scotland to be crowned as king on 1 January 1651. Later in the year he led a last-ditch invasion of England to regain his English throne. This was against the advice of David Leslie, the defeated commander at Dunbar.

In August 1651, 14,000 Scottish troops crossed the border. Cromwell, who was still reducing Scotland, followed Charles and collected reinforcements as he headed south. The New Model Army caught up with the invading army at Worcester on 3 September, one year to the day since the Battle of Dunbar. By this time, Cromwell’s force numbered 28,000 regular troops and 3,000 militiamen. This was the first occasion when the New Model Army had overwhelming numerical superiority and Cromwell’s confidence was at its peak.

The Battle of Worcester took place in a wide area around the city. Cromwell attempted to encircle Worcester in order to force Charles into a defensive position within its walls. However, to the south and south west of Worcester, the Rivers Severn and Teme blocked the army’s advance. These would need to be crossed in order to carry out the battle plan, so Cromwell began the fight by personally leading three brigades to attack the pontoon bridge on the River Teme. Once the north bank had been taken, the Scots collapsed back towards Worcester itself. While Cromwell was crossing the rivers, the east flank of his army was threatened when Charles II rallied his troops to sally out of the town and assault the New Model infantry. This surprise attack was initially successful and there was a moment when the entire east wing of the army almost collapsed. However, Cromwell came charging back from his position on the River Severn to bolster his troops.

The return of his brigades turned the tide of the battle and the Royalists were thrown back into Worcester. At this point, Parliament’s Essex militia stormed and captured Fort Royal, which was a defensive entrance into the city. Once the guns inside were taken, they were turned on the Royalists in the town itself. The final part of the battle then played out in fierce street fighting. Running skirmishes sparked out all over the city, and the Royalists eventually panicked and fled for their lives. Charles II was among those who fled, and after several legendary adventures while hiding from the enemy, he eventually escaped to the continent. The vast majority who followed him were not so lucky – 3,000 Scots were killed at Worcester and another 10,000 taken prisoner, most of who were transported to the colonies as indentured slaves.

For the New Model Army, the Battle of Worcester was a triumph, as well as the last major battle of the Civil Wars. The Parliamentarians had only lost 200 men on the field, which had seen among the first skirmishes of the Civil Wars back in 1642. Cromwell described Worcester as a “crowning mercy” and it was to be his final battle as an active commander. Nevertheless, the New Model would continue as the backbone of the Commonwealth throughout the 1650s, achieving a last hurrah in the dying days of Cromwell’s Protectorate, at the Battle of the Dunes.

International Respect

Taking place on 14 June 1658, the Battle of the Dunes was a victory for a combined Anglo-French army commanded by the Vicomte de Turenne against the Spanish. Cromwell had agreed to form an alliance with the French to put pressure on the exiled Charles II and to acquire the English Channel port of Dunkirk by diplomatic means. France was at war with Spain and Dunkirk itself was part of the Spanish Netherlands, which meant that it would need to be taken by force.

Turenne besieged Dunkirk with 15,000 troops, of which 3,000-4,000 were red-coated soldiers of the New Model Army. A Spanish force of 15,000 men was sent to relieve the town, about 2,000 of whom were English Royalists led by the Duke of York, the future James II. The upcoming fight would be a miniature replay of the Civil Wars re-created on a European stage.

The battle played out on coastal sand dunes that lay north east of Dunkirk. Turenne took the initiative and attacked the Spanish entrenched in strong defensive positions among the dunes. English Major-General Thomas Morgan and Sir William Lockhart commanded the New Model contingent and it was Lockhart’s Regiment of Foot that particularly distinguished itself. They astonished both the French and Spanish with the ferocity of their assaults against enemy positions. Lockhart’s regiment in particular launched a dramatic attack on a Spanish-held sand hill that was 150 feet high. The speed of the English attack took the hardened Spanish veterans defending the hill by surprise, and after a tough fight, the French came to support the English and the Spanish were driven away. Soon afterwards, the battle was decisively won for the Anglo-French army.

Dunkirk fell and was gifted to the English, but more importantly for the Protectorate, it also prevented the restoration of Charles II for another two years. The Battle of the Dunes demonstrated to the European powers that the New Model Army was one of the best fighting forces on the continent – one that would make England a power to be feared and respected.

Images courtesy of Future PLC Asset Library

For more fascinating stories from military history why not purchase a cost-saving subscription to History of War? For more information visit: www.myfavouritemagazines.co.uk